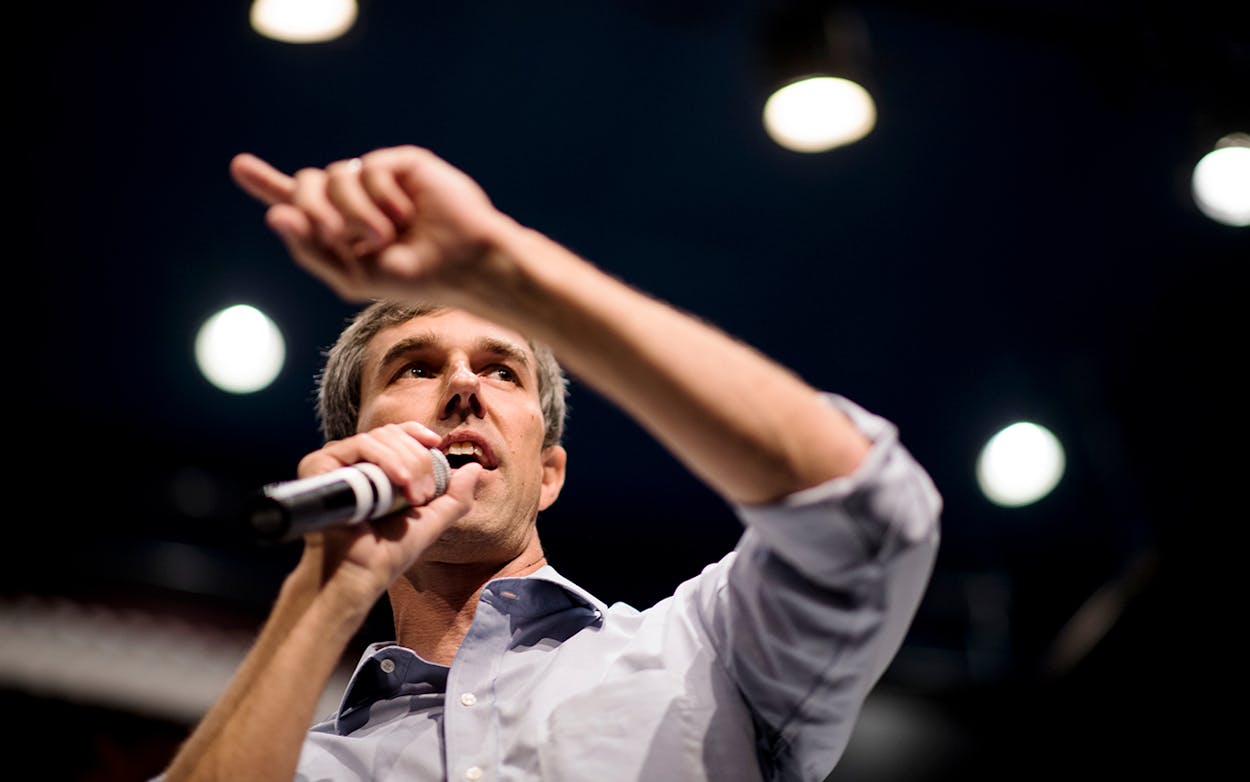

The day after Beto O’Rourke lost his closely contested Senate race against Ted Cruz by 2.6 percent, I heard an argument that convinced me that O’Rourke’s next political step was obvious: He needed to run for Senate again in 2020.

Political scientists Jim Henson and Josh Blank of the Texas Politics Project at UT-Austin had laid out the case. O’Rourke had nearly pulled off one of the most stunning electoral upsets in the history of the union. He’d built up a massive database of voters and volunteers and donors. He’d gone from being virtually unknown outside of El Paso to a national celebrity. He’d done it all in a midterm election—and Democratic candidates up and down the ballot almost always perform worse in midterms than in a presidential year, when turnout is higher.

“He’s fresh in people’s minds, the lessons he’s learned from running statewide are fresh, the enthusiasm is there, and the structural conditions are only better in 2020,” Henson said.

Those conditions started with Donald Trump, who would be on the ballot, and could help spur massive turnout to defeat him. But it also included O’Rourke’s presumptive 2020 opponent. While some pundits claimed that O’Rourke got lucky in trying to unseat a politician as widely loathed as Ted Cruz, Henson and Blank said the numbers didn’t bear this out. Sure, Democrats and a lot of Washington Republicans loved to hate Ted Cruz, but Texas’s junior senator had proved time and again that he was a tenacious campaigner and polls had consistently shown that Texas Republicans were fiercely loyal to him. John Cornyn, who’s held his seat since 2003, might not have been late-night television cannon fodder, but his support was softer too. There was a perception that Texas’s mild-mannered, establishmentarian senior senator couldn’t quite rile up the base in the age of Trump, and the numbers indicated that might be true. In their pre-election poll, Henson and Blank had found that while 87 percent of Texas Republicans approved of Ted Cruz, only 70 percent approved of Cornyn. Yes, the numbers also showed that Democrats hated Cornyn a whole lot less (only 44 percent strongly disapproved of him, compared with 76 for Cruz), but, as Trump himself could tell you, no one wins elections these days by being less repellant to voters in the opposite party. Plus, Blank added, “O’Rourke already has better name ID.”

As I sat listening to Henson and Blank, the question wasn’t whether it made political sense for O’Rourke to run. It was whether Cornyn would even seek a fourth term if it meant a knock-down, drag-out fight with a political and fundraising superstar named Beto O’Rourke.

On November 7, the possibility that O’Rourke would run against Cornyn seemed very real. Two days before, he had told MSNBC, “I will not be a candidate for president in 2020.” But less than a month later, he cracked the door open, saying that he and his wife, Amy, had “made a decision not to rule anything out.” Since then, O’Rourke has been seemingly running for president in fits and starts, granting interviews to national journalists, going on a solo road trip into the American Heartland, live-streaming a dental visit, and, most consequentially, refusing to state one way or the other whether he’s running, leading early primary state operatives, Democratic donors, and two separate “draft Beto” efforts to try to convince him to enter the presidential primary field. This afternoon, O’Rourke will appear onstage with Oprah Winfrey at the PlayStation Theater in Times Square. O’Rourke may announce he’s running for president, or he may say he needs more time. But one thing that seems almost certain is that he will not choose a Chicago-based host and a New York venue to announce he’s running for Senate in Texas.

O’Rourke’s spokesperson Chris Evans told me in an email last night that “Beto hasn’t ruled anything out,” but most Texas political observers I’ve talked to think it’s increasingly unlikely he’ll run for Senate, and many O’Rourke supporters in Texas seem just fine with that. “I think winning statewide is harder than capturing the presidential nomination for Beto O’Rourke,” Mikal Watts, a San Antonio lawyer and major Democratic donor, told me. “And which would you rather be, one of 100, or the top guy?”

One thing that seems almost certain is that Beto will not choose a Chicago-based host and a New York venue to announce he’s running for Senate in Texas.

But if O’Rourke doesn’t run against Cornyn, who will? The structural conditions that would make a Senate run in 2020 so enticing for O’Rourke would also be there for another Democratic candidate. You might think that ambitious Texas Democrats would be lining up to run, all but declaring their candidacies in the event that O’Rourke should decline to pursue the Senate seat. (If O’Rourke decides to run against Cornyn, he’ll almost certainly clear the Democratic field.) After all, O’Rourke discussed the possibility of running for Senate in 2018 in early November 2016. We’re already in February 2019. Where are the candidates?

“The conversations would be very quiet now,” said Matt Angle, the founder of the Lone Star Project, a progressive PAC. “You don’t want to say it would be really great if someone else runs and then Beto runs instead.”

So far, the Democratic field seems to be characterized more by high-profile candidates who are unlikely to run than those who are champing at the bit should O’Rourke declare for president.

San Antonio congressman Joaquin Castro, the consensus choice for next in line to run for Senate? His next two years are seemingly already accounted for. He has just taken on the role of campaign chairman for his brother Julian’s presidential effort; he was recently named chair of the Congressional Hispanic Office; and, for the first time in his career, he is a member of the majority in the House of Representatives.

The promising group of newly elected Democratic U.S representatives—Colin Allred, Lizzie Fletcher, Veronica Escobar, and Sylvia Garcia? Well, Texas law prohibits candidates from seeking two offices simultaneously (there’s an exception for president and vice-president), so they’d be forced to trade in a job they just won for an uphill statewide race.

The nearly as promising group of 2018 congressional candidates who came close to winning their traditionally Republican districts, among them M.J. Hegar, Joseph Kopser, and Sri Kulkarni? Well, it’s possible, but the DCCC is already targeting the districts they almost won, and those candidates’ clearest shot to political victory would seem to be to run for Congress again.

When I spoke with Jason Stanford, a former Democratic strategist who is now an executive at the public relations firm Hill + Knowlton, he insisted that Democrats have a “deeper bench in Texas than people suspect.” He pointed to Dallas state representative Rafael Anchia, Dallas County judge Clay Jenkins, former gubernatorial candidate Wendy Davis, and Mark Strama, a former Texas state rep who is now an executive at Google Fiber. These four people might make fine candidates and senators, but aside from Davis, they have almost no statewide profile. They’re not the names you’d expect to hear bandied about if Democrats thought the 2020 Senate seat was theirs for the taking.

Maybe O’Rourke will run for Senate after all. Maybe a new face like Allred or Garcia or Hegar will gamble their political future on a Senate run. Maybe a big-city mayor like San Antonio’s Ron Nirenberg will go for the prize. Maybe a lesser-known name from the bench like Anchia or Jenkins will catch fire. Kim Olson, the Democrats’ 2018 candidate for agriculture commissioner, has suggested she’s considering a 2020 run.

But some Democrats aren’t convinced a strong option will materialize. “If Beto doesn’t run for Senate, I’m not convinced we’ll have a strong viable candidate,” Harold Cook, a Democratic political operative, told me. “I fear that a lot of the most prominent Democrats who might want to run may well conclude that Beto got so close either because Beto is a one-of-a-kind candidate or that Cruz is so intensely disliked that no other opponent would fare as badly as he did.”

On the trail, O’Rourke liked to undercut his own exceptionalism by saying, “we’re part of something really amazing going on in Texas.” That may sound like a politician’s calculated humility, and it was, but O’Rourke might have also meant it. He accurately predicted that he’d have a shot in 2018 when most people gave him no chance at all, and thanks in large part to O’Rourke, 2020 doesn’t look like such a steep climb. How many Democrats will heed O’Rourke’s example, seize an opportunity, risk their political future, and run?

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- John Cornyn

- Beto O'Rourke