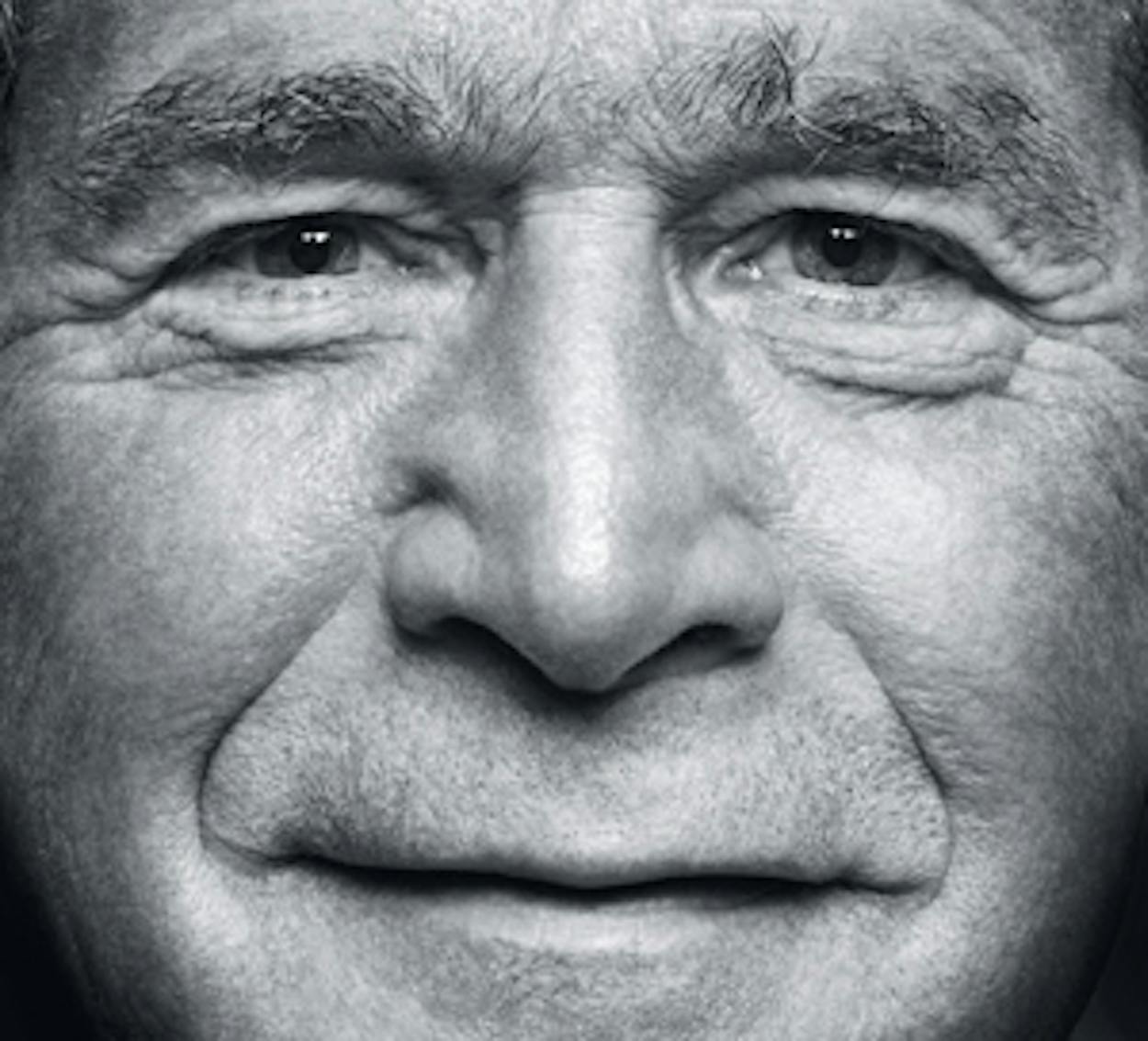

To see George W. Bush now, open-collared in a sports coat and slacks, sitting comfortably behind his desk in a sleek corner office, a view of downtown Dallas several miles in the distance, is to see a man who seems genuinely content with having left the White House behind. His office doesn’t look like that of a former president. Except for the enlarged photos of him with world leaders that line the halls and the framed shots of his famous family arranged neatly on a credenza, it could be the generic quarters of a C-suite executive at Citibank or Ernst & Young. Nothing particularly presidential is on display, no flag or seal, no intricately carved oak desk, no Frederic Remington sculptures. And that may be the point—Bush has moved on.

To see George W. Bush now, open-collared in a sports coat and slacks, sitting comfortably behind his desk in a sleek corner office, a view of downtown Dallas several miles in the distance, is to see a man who seems genuinely content with having left the White House behind. His office doesn’t look like that of a former president. Except for the enlarged photos of him with world leaders that line the halls and the framed shots of his famous family arranged neatly on a credenza, it could be the generic quarters of a C-suite executive at Citibank or Ernst & Young. Nothing particularly presidential is on display, no flag or seal, no intricately carved oak desk, no Frederic Remington sculptures. And that may be the point—Bush has moved on.

We hadn’t heard much from him since January 20, 2009, when boos from partisan members of the record-breaking crowd at Barack Obama’s inauguration could be heard directed toward the outgoing commander in chief. Observing a tacit rule among “formers,” Bush maintained a low profile, slipping back into private life and enjoying his $3 million, 8,501-square-foot home in Preston Hollow and the company of his family and friends. Aside from off-the-record speaking appearances, which often fetch six-figure paychecks, he stayed out of the public eye. That changed in November, as he presided over two events that have become milestones in the lives of ex-presidents: the publication of his memoir and the groundbreaking of his presidential library. The events may also mark the unofficial beginning to a more active—even activist—post-presidency that Bush may pursue, using the George W. Bush Presidential Center (a 25-acre complex at Southern Methodist University that will include his presidential library and museum, the offices of his foundation, and the George W. Bush Policy Institute) and his influence to pursue causes of importance to him, much as Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter have done.

Which is what I’d come to talk about on a sunny Tuesday in late October, a week before the midterm elections that Bush would watch from the sidelines—all too happily. “The scene is a swamp out there right now,” he told me, “and I don’t want to get in the swamp.” Not a bad time to be a former.

UPDEGROVE: Mr. President, how did you find leaving the most powerful position in the world and going back to being a private citizen?

BUSH: I woke up the next morning, and one thing you had to learn was that you no longer had the sense of responsibility that became ingrained in your system. So I read the newspapers, the Dallas Morning News and the Waco newspaper. I saw the headlines, and there was a “What are we going to do about this?” And then I realized, it wasn’t me. It was my successor.

So I gathered up Barney and Beazley, got in the pickup truck, drove over to my office, and started writing anecdotes for my book. I occupied my time with projects. The major project was writing the book but also beginning to raise money to get this library and institute not only funded but get the strategy in place.

And then my speaking engagements began. They are fun events. They’re all off-the-record—a couple of them weren’t initially, but they’re now all off-the-record. I was a little taken aback at first with being paid to give speeches. I had done it for fourteen years for free, and all of a sudden somebody’s willing to pay me—it didn’t take me long to adjust.

And I stayed fit. I wanted to make sure that my fitness was strong, so I rode my mountain bike a lot, and then I took up golf, or retook it up. The interesting thing about golf is, the presidency requires focus and discipline, and golf requires focus and discipline. It was a way to make sure that parts of my life were focused and disciplined.

UPDEGROVE: Your father had been there before you. Did he help in the transition?

BUSH: He helped in this sense: I watched him carefully. He moved on with his life—he didn’t linger. I learned from him that when it’s over, it’s over. I view my time in politics as a chapter, not my life. I’m forever a former president and I understand that, but at this point in my post-presidency, I really don’t want to be involved with politics. Secondly, I don’t want to interfere with my successor’s presidency.

UPDEGROVE: Let’s talk a little bit about [your book] Decision Points. It is my understanding that the process of writing a memoir can be very cathartic.

BUSH: I think it is.

UPDEGROVE: How so?

BUSH: Ironically enough, by focusing on your presidency, it helps you realize that you’re no longer the president. I spent a lot of time on this book. You know, I’m a content person and I’m content knowing that I gave it my all when I was president. But I’m also content because I’m a busy person. I don’t think you can run for president or be president unless you’re a busy person. The book kept me busy. Telling [my] story adds finality to the presidency.

UPDEGROVE: You wrote about key decisions in your life and presidency. Upon reflection, were there any that you thought better of?

BUSH: When people read my book, they will see that I am very comfortable with the strategic decisions that I made. No matter how tough Iraq became, removing Saddam Hussein was the right thing to do for the sake of peace and for the 25 million people we liberated. Denying Al Qaeda safe haven was the right decision. Using taxpayers’ money to provide liquidity to Wall Street so that the country wouldn’t head into a depression was the right decision.

There were tactical decisions that I wish I could have done differently: “Mission Accomplished,” not revealing my drunken driving charge prior to my run for the presidency, flying over New Orleans on Katrina and the pictures being released and people saying, “He’s aloof and doesn’t really care.” There are a lot of tactical decisions that, if I could have done them over, I would have.

UPDEGROVE: The publication of a memoir is often the first step for a former president in launching a more activist post-presidency. You saw that with Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter and others. What are your plans for your post-presidency?

BUSH: My post-presidency is evolving. Laura and I will be very much involved with the Bush Center. I tell people this is a way for us to be involved in policy and not in politics. I believe that we’re in an ideological struggle; I believe the only way to marginalize those who murder the innocent to achieve their ideological objectives is to spread democracy and freedom.

Laura and I will be involved with working with women in the Middle East, because I believe that women will lead the democracy movement. Now, what I’ve just described is controversial. There are some who say, “It’s a pipe dream that people in the Middle East will live under a democracy.” Some say, “Who cares if they live under a democracy.” But I think it’s important for the country, and I do care. Therefore, I’m going to be involved with freedom; I’m going to be involved in the marketplace; I’m going to be involved in the accountability in schools. And helping people devise a strategy that makes public and private moneys more effective when it comes to helping save lives. Those four areas of engagement will occupy a lot of my time.

And that’s the fundamental difference between that kind of activism and an activism that intrudes into the life of the current president. I can change, but as we speak now, I really have zero desire to see my name in the press. I tell people that one of the biggest sacrifices in running for president, if there is one, is loss of anonymity. I realize I will never regain my anonymity, but I can certainly give it a try. And it’s a lot of fun to give it a try.

UPDEGROVE: I want to talk about your institute in a moment, but let me go back to other former presidents. Is there a former president whom you would like to emulate?

BUSH: George H. W. Bush. He’s been a classy guy in his post-presidency. When I called upon him and President Clinton to help in the tsunami and Katrina, he said, “I’d love to, son.” He is gracious. And I’m not saying the other former presidents aren’t gracious; I’m just saying this man is gracious. But each of us will figure out our own way. I can only give my life in a way that makes me comfortable, and I am uncomfortable at this point in my post-presidency going on the Sunday talk shows.

What would be interesting is if you come back five years from now and see what I’ve done. I suspect you’ll come back and say, “Well, you really haven’t been in the press. You gave a speech because they asked you to at a convention perhaps.” I think you’ll come back and say, “It’s interesting what you’ve done with veterans.” I’m beginning to get a sense of how active I’m going to be with veterans. I feel a special kinship with our military personnel and their families. After all, two of my decisions sent them into harm’s way.

UPDEGROVE: One of the differences between your post-presidency at this point and your dad’s is that your dad once told me he didn’t want to “save the world.” The George W. Bush Policy Institute has some pretty high ambitions all around core areas that are of interest to you: education, economic growth, global health, and human freedom. What do you want to accomplish ultimately?

BUSH: Well, there’s a lot that I want to accomplish. One, I believe in a core set of principles. I believe that freedom is a gift from an Almighty to every man, woman, and child; markets are the best way to allocate resources; to whom much is given, much is required; all human life is precious. In other words, these are certain principles that need to be defended. The programs will be built around those principles. The freedom movement is built around the principle of democracy, of the universality of freedom.

From a philosophical perspective, I want to fight off isolationism and protectionism. I worry about a nation withdrawing and saying, “It’s too hard. Let’s forget what’s going on over there.” I also worry about protectionists, which is another way of saying less competition, less trade around the world. And I view those as twins of negativity.

UPDEGROVE: You did not have a reputation of being a micromanager in the White House.

BUSH: I wasn’t.

UPDEGROVE: What will the extent of your involvement in the institute be?

BUSH: One is to make sure that we stay focused on core principles. Secondly, I will be a recruiter of talent. Thirdly, I will work on the fund-raising side. I will be a part of the thought process about how to make sure that the platform we have developed is effective and innovative. The programs will give us a chance to be more than just a think tank; it will be a results-oriented place. I can’t tell you all the programs that will emanate out of here, but I can pick up the telephone and say to a world leader friend of mine, “Come on over. Would you mind sharing your thoughts about . . .?” And more than likely, if it works, they’ll come.

UPDEGROVE: When one looks at what Carter and Clinton have done, it’s pretty clear that they pursued agendas that were unfinished from their presidencies. To some extent, it seems as if they pursued them to burnish their legacies. There are those who could look at the core areas that you’re focusing on as being the areas that you would want to be remembered for as president.

BUSH: It could be. I tell you, I would like to be remembered as president as somebody who did not compromise principles in order to try to be loved or liked. So to the extent that the center is going to remain focused on certain principles, maybe that reinforces something I’d like to be known as. It was a privilege to be president, and it is a privilege to be a former president, and I believe that I have got a chance to be a part of something influential—but not for my sake. For the sake of people dying in Africa or people worried about a free society in their countries or people who wonder whether there will be a free market.

You know, if someone came to me and said, “Your strategy in your post-presidency is brilliant,” as if I had figured out a way to make me look better, to me, that analysis is amusing. I decided what I wanted to do, not to make me look good but to make me feel comfortable. Other presidents do it other ways. You know, Bill Clinton and I are friends; we see each other on the speaking circuit. He likes to be visible. I don’t. And I draw no judgment either way.

UPDEGROVE: Mr. President, you mentioned Africa, and I think there are many people who would be surprised to the extent that you aided Africa for no immediate gain to the United States.

BUSH: I’m surprised that they’re surprised. As a matter of fact, I’m surprised at the number of people who walk up to me and say, “You’re a lot taller than I thought you were.” What ends up happening is people form images, and the image they form is, in some ways, what they want it to be. The idea of trying to correct the image is something I’m not interested in doing. And I’m comfortable with time. Time will change.

UPDEGROVE: No sitting president did more to aid Africa than you. What was the motivation behind that?

BUSH: Two factors. One, I believe strongly that to whom much is given, much is required. We are a blessed nation, and the United States could affect suffering in a positive way. Secondly, I viewed the issue from a national security perspective. You have to understand, my presidency—and the country, of course—was significantly affected by 9/11, and my thinking was significantly affected by 9/11. I clearly saw the ideological conflict we faced with our enemy. If you are a young child and you’ve lost your mother and dad to AIDS and rich nations sit on the sidelines not caring, you will become a frustrated person and a hopeless person. We face an enemy that can only recruit when they find hopeless people—you’ve got to be pretty hopeless to become a suicide bomber. So my justification for the program was one moral justification and one national security justification.

UPDEGROVE: Do you feel like the press mischaracterized your administration?

BUSH: I don’t know. I felt like they mischaracterized my dad’s administration. I had watched his presidency in agony. I tell the story about when Newsweek put the “wimp” label on him. God, was I mad. I developed a reputation as a hothead, because I got in the face of a lot of reporters, and they thought I was just a hotheaded person. What they didn’t understand was that I was motivated by love. I tell people, 1992 was the worst year of my life, to watch my dad lose. It was a painful experience.

It was so much easier to be president. But for him, it became painful, because he paid attention to all the characterizations. I didn’t, I really didn’t. It came with the territory. It was much easier for me to endure the belittling than it was to watch my dad get belittled.

UPDEGROVE: What you said about your dad is exactly what he said about you on the eve of your election. He told me he didn’t care when the slings and arrows were directed at him, but when they were directed at his son . . .

BUSH: Here’s the story. I would call him, and Mother would answer the phone and say, “Your father . . . I can’t believe he’s listening to all this stuff. George, you need to talk to your dad.” And I became the comforter. I’d say, “Hey, Dad. I’m doing great. I know it’s tough out there, but don’t worry about me.”

And so our roles got reversed. I’d call him and check in with him and say, “How are you doing?” and he’d say, “Can you believe what they wrote about you, said about you . . .?” I’d say, “Dad, don’t pay attention to it. I’m not. I’m doing great. Don’t worry about me.”

What people can’t possibly imagine is what it’s like to have two presidents who have a relationship as father and son. They envision us sitting around the table endlessly analyzing the different issues and strategies and tactics. It’s much simpler than that and in many ways more profound.

UPDEGROVE: It’s clear that you take the long view of history.

BUSH: I did, and I think all presidents should take the long view of history.

UPDEGROVE: But, I wonder, what will history say about George W. Bush?

BUSH: You know, I don’t know when history will objectively judge my administration. I know this: I’m not going to be around to see it. And so I’m comfortable knowing that I put my heart and soul into the presidency. I am comfortable that the principles that I articulated were never compromised. And I am honored to have served.

Now the question is, Will I be satisfied with the rest of my life? As I look back over my life, I’ve been an active person—obviously I was self-absorbed for a period of time. But my mission is to use my status, primarily through the Bush Institute, to affect people’s lives positively. I can’t give you the specific strategy; I can just tell you right now that I am comfortable with how I am living my life.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- George W. Bush