This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

A generation of hamlets

On a sunny day in April, a skinny tourist kid from Joplin, Missouri, saunters into the former Texas School Book Depository in downtown Dallas and heads toward the sixth floor, better known as the JFK assassination exhibit. Passing through security guards and airport-regulation metal detectors at the exhibit’s entrance, the kid becomes incredulous. “What’s with all the security?” he asks. “I mean, they aren’t going to shoot Kennedy again, are they?”

On the sixth floor, however, that is precisely what is happening. No one is looking at the exhibit—a multimedia display of pictures, placards, and the original radio and TV reports. Instead, the $4-a-ticket crowd gathers around the six south windows, only a few feet from Lee Harvey Oswald’s corner perch. Now, instead of an assassin at the glass, there is this crowd watching a procession of sixties statesmen in big-finned black Cadillacs and Continentals float down Houston Street toward the infamously orange Texas School Book Depository, which looks exactly as it did in 1963. The cops drive black-and-white 1963 Ford Galaxies and Harleys, and the parade throng on Elm Street is decked out in razor-thin ties, scarves, and sixties innocence. All to greet Jack and Jackie, who are young again and waving. “It’s beautiful, beautiful,” swoons a woman at the sixth-floor windows.

Suddenly, a shot rings out. Then another. And then several more. A cloud of blood explodes in the air, and Kennedy clutches his throat. As Jackie frantically climbs across the trunk of the convertible, the crowd in the street scatters in fear and pandemonium, and the woman at the sixth-floor window breaks into tears. Real tears. Not just for the blank bullets but also for the thought that has lingered in the American consciousness for 28 years: Had Kennedy lived, everything might have turned out differently.

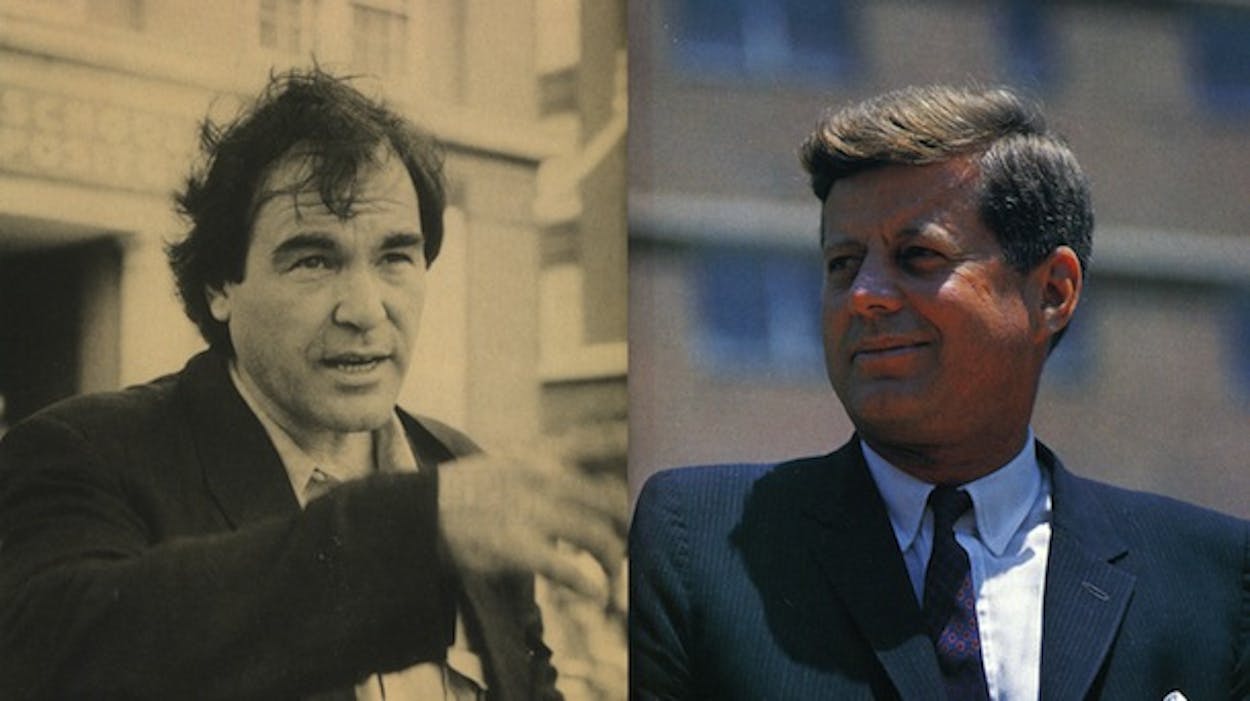

This time, there is no doubt who is behind the assassination in Dealey Plaza. Standing atop the grassy knoll, so full of angst and anger that he once told an interviewer that he himself might have assassinated Richard Nixon had the right people approached him at the right time, is Oliver Stone, the Academy award–winning director, screenwriter, and celluloid crusader, whose films have revived the sixties from Vietnam to Jim Morrison. Stone is a filmmaker of unforgettably brutal images: James Woods running amok in Salvador; Charlie Sheen baptized by blood in Platoon; Michael Douglas slithering across Wall Street; Tom Cruise paralyzed, impotent, and forgotten in Born on the Fourth of July; Val Kilmer making love with death in The Doors. This is Oliver Stone’s world on parade. Now Hollywood’s master of rage has come to Dallas to recreate the end of American innocence in JFK, a three-hour, $40 million epic. With JFK, Stone aspired to do for the Kennedy assassination what Platoon did for Vietnam: make it live again for the world to question. He calls the assassination the seminal event of his generation and says it left behind “a generation of Hamlets”—children of a murdered king whose killers have inherited the throne.

The DA and the CIA

Scheduled to open December 20, JFK is partially based on a 1988 book by controversial former New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison, On the Trial of the Assassins. Garrison believes that the assassination was the result of a coup d’état conducted by rough forces within the Central Intelligence Agency determined to stop Kennedy from ending the Cold War and sanctioned after the fact by Lyndon Johnson. The book’s theories, whether plausible or not, are the perfect bedrock for an Oliver Stone tale of deception, death, and deliverance. As Stone’s protagonist, there is Garrison, played by a drawling Kevin Costner, who unwittingly stumbled onto the crime of the century after discovering that Lee Harvey Oswald (Garry Oldman) spent the summer of 1963 in New Orleans. Obsessed with perceived lapses in the Warren Commission report—testimony ignored, facts jumbled, documents sealed or destroyed, a commission of CIA intimates swiftly ratifying its lone-nut conclusion—Garrison brought to court the only criminal prosecution in the murder of John F. Kennedy.

In the book, Garrison’s trial begins on the night of the assassination, when private eye Guy Banister (Ed Asner), a former agent for the Federal Bureau of Investigation, gets sloppy drunk and pistol-whips his associate, Jack Martin (Jack Lemmon). The reason? Martin told Banister that he hadn’t forgotten the happenings in Banister’s office that summer—an office that served as a center for a collection of oddballs plotting against Castro, a wild parade of fanatical anti-Castro Cubans and mercenaries, notably Oswald and David Ferrie (Joe Pesci). A crackerjack CIA pilot, Kennedy hater, and drag queen, Ferrie wears greasepaint eyebrows and a crude mohair wig. Ferrie’s activities, however, are wilder than his appearance, especially a hasty trip to Texas on the day of the assassination. Tipped that Ferrie was supposed to have been the getaway pilot for the assassins, Garrison builds his case. Bringing charges, however, isn’t easy. Banister died nine months after the assassination. And Ferrie dies suspiciously in the middle of Garrison’s investigation, leaving the DA to arrest supposed conspirator Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones), a New Orleans business titan with CIA connections. Along the way, Garrison tracks Oswald through New Orleans, Dallas, and Russia to Dealey Plaza, where, according to Garrison, the supposed marksman was not at the sniper’s perch but in the School Book Depository’s lunchroom.

Before Shaw is brought to trial, Garrison’s case begins to crumble. The FBI attacks the investigation and shadows Garrison and his staff. Crucial witnesses die. Files are stolen from Garrison’s office as fast as phone taps appear. Requests for extradition of key witnesses are denied. And while the 1969 trial provides evidence contrary to the Warren Commission’s conclusions, a jury rapidly exonerates Shaw. Members of the media, from Johnny Carson to Garrison’s hometown Times-Picayune, label the district attorney a publicity-mad buffoon. Even Garrison’s wife, played in the film by Sissy Spacek, worries about her husband’s obsession.

By lacing Garrison’s story with scores of black and white flashbacks to assorted assassination theories, Oliver Stone has picked up where Garrison left off. And the filmmaker has become equally obsessed—and vilified. On the set, there are rumors of CIA operatives lurking about, fed by Stone’s accusation that a right-wing CIA-inspired press is intent on discrediting his film before it is even released. Conspiracy buffs have trundled into town as if headed to a convention. And although the set is closed during filming and ringed with security guards, spectators are packed five-deep at barricades, while the craftier pay the $4 admission to watch the shooting from the sixth floor, where real assassination figures, such as retired Dallas police detective James R. Leavelle, sign autographs and espouse theories.

Leavelle’s grimace became part of history: He was handcuffed to Oswald when Jack Ruby shot the prisoner. Now he is one of Stone’s many technical advisers. But whenever Stone frames a shot that Leavelle doesn’t believe, he leaves the director in the street and heads to the sixth floor for solace. “I just had my picture took with Kevin Costner,” he brags to the crowd. And his listeners bolt from the old detective to stare through the windows at Costner, in jeans and cowboy boots, right there on Houston Street.

The moment will surely be noted in the Dallas Morning News’s weekly “Kevin Watch.” Meanwhile, paparazzi have descended from around the globe. A typical comment from the cynical British gang: “Now, if someone from the lunatic fringe of America shows up with a real gun, we’d really have a world-class story.” On the first day of filming, a man in camouflage gear is apprehended by security. But instead of a gun, he is brandishing a video camera.

All of the familiar characters are present, risen from the grave in the bodies of movie stars. British star Gary Oldman is playing Lee Harvey Oswald to the hilt. “Every um and ah and pause is absolutely accurate,” he says. “I do the voice. I do the walk. I do the head movements. Where his eye moves. Where he licks his lips. Everything. I studied for months.” Filming a flashback to the Warren Commission’s lone-gun conclusion, Oldman crouches as Oswald with the mail-order Mannlicher-Carcano rifle in a seventh-floor window that has been made to look like the sixth, stocked with three thousand book cartons and an air of utter loneliness. “You get to Dealey Plaza. You go up to that window. And the first thing you say to yourself is, ‘Impossible,’” says Oldman. “The distance. The angle. You want to take the Warren Commission report and burn it the moment you stand up there.”

Leading his cameras, which bob and weave as if in a fistfight, Stone races about Dealey Plaza as the motorcade rolls and the shots explode. Using the techniques of films such as Kurosawa’s Rashomon and Costa-Gavras’ Z, in which several possible scenarios of an event are seen and the audience is allowed to form its own conclusion, Stone is shooting Kennedy from every point of view. He shoots Kennedy from the sixth floor, where the Warren Commission placed Lee Harvey Oswald. He shoots Kennedy from the stockade fence atop the grassy knoll, from which 78 witnesses heard gunfire. He shoots Abraham Zapruder shooting his home movie of Kennedy, and both footages will be seen in the movie. And downtown Dallas echoes with the sounds of November 22, 1963.

In unleashing the ghosts of Dealey Plaza, Stone has forced Dallas to rip open its old wounds and reexamine them. “I suppose it is a sign of Dallas’ maturity that people here are far more concerned about the number of downtown streets Oliver Stone has closed than what he is going to say about us,” Dallas Morning News editorial columnist Henry Tatum writes during the first week of filming. But perhaps the Dallas Times Herald puts the movie in better perspective, quoting black militant city councilman Al Lipscomb: “It’s good. We need a good therapeutic enema . . . to make sure there will be no residue of the past.”

But Morning News columnist William Murchison uses the filming of JFK to defend the old Dallas: “Oliver Stone, America’s favorite anti-American filmmaker, has downtown Dallas traffic tied up while he recreates the Kennedy assassination for his upcoming flick. Why not? The Kennedy assassination has tied up Dallas for 28 years—hogtied, hamstrung, bollixed and bumfuzzled it.” Murchison mourns the individualistic, entrepreneurial Dallas that, he says, died with Kennedy and lambastes the soft-bellied, insecure Dallas that took its place: “Oliver Stone’s traffic jams are the abasement we deserve. He gets to block traffic and insult the whole city because, well, he’s a big man and we wouldn’t want such a man thinking ill of Dallas. . . . How tame, how servile and cringing is the spirit of the old west.”

“Kennedy Committed Suicide”

Oliver Stone’s rise in the world of conspiracy theories came in an appropriate setting. During a break in the 1988 filming of Born on the Fourth of July, Stone got stuck in a painfully slow socialist elevator in Havana, Cuba. He was there to accept an award for Salvador at the Latin American Film Festival. In the crawling elevator at the Capri Hotel, he encountered Ellen Ray, a firebrand documentary filmmaker and publisher and editor of magazines such as Lies of Our Time, which exposes “misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda in the major media.” Ray had gone to New Orleans before the 1969 Clay Shaw trial to do a documentary film on Jim Garrison. Now she was at the film festival touting the galleys of Garrison’s upcoming book, and she seized the moment.

“Have I got a property for you!” she exclaimed. She described the thesis of On the Trail of the Assassins. Stone didn’t bite.

“Yeah, yeah, sure,” said Stone. “Send it to my office at [Twentieth Century] Fox.”

Ray sent the galleys. Two days later, Ray recalls, Stone phoned. “He said, ‘It’s a great book, but I can’t do it. I’m on my way to the Philippines to film Born on the Fourth of July. But you won’t have any trouble selling it.’ Two days later, he called from Hawaii, saying ‘I just read the book again on the plane. I can’t do it. I’m overloaded.’ Three days later, he called from the Philippines, saying, ‘I’m hooked. I’m going to option it.’”

As a movie hero, Garrison was not unblemished. During the Clay Shaw case, the district attorney had been accused of bribing witnesses, gaining testimony by hypnosis, manufacturing evidence, and much, much more. Garrison was eventually indicted for bribery and tax evasion after the Clay Shaw trial (he was found not guilty in both). He was assailed for his alleged relationship with the Carlos Marcello crime family, whose members he had never brought to trial. But Garrison had explained away many such episodes in his book. Stone was convinced that Garrison was “a protagonist of merit.” Warner Brothers committed $40 million to back up Stone’s instincts.

By the fall of 1990, Dallas was buzzing with rumors that Oliver Stone was coming back to town. In 1988 he had filmed part of Born on the Fourth of July in Oak Cliff, transforming an economically battered area into cheery 1966 Massapequa, Long Island. The first hint of Stone’s new interest came, appropriately, in Oak Cliff, after United Artists Theaters announced the closing of the 1,350-seat Texas Theater, where Oswald was arrested in 1963. Considered one of the premier theaters in the state when it was built by Howard Hughes in 1931, the Texas was being closed after years of B-movies and no profits. Immediately, a Texas Theater Historical Society was formed. The recipient of one of its first calls was Oliver Stone. Would he allow a benefit screening of Born on the Fourth of July to raise a down payment to save the theater? Stone did better than that. He paid the closing costs to buy the theater, and musician Don Henley, who filmed part of his End of Innocence video at the theater, provided the down payment.

Nobody knew that Stone’s crews were already scouting Dallas for a movie about November 22, 1963. “Usually, Oliver is sort of cagey on what he does next,” says JFK coproducer Clayton Townsend, who first got wind of the project in 1988, when Stone tossed him the Garrison book. A year and one movie lapsed before the subject resurfaced. Toward the end of shooting The Doors, Stone told Townsend, “We’re going to New Orleans to do some research on On the Trail of the Assassins.”

Stone likes to compare Garrison to a heroic Everyman seeking the truth against insurmountable odds. But from the beginning, the analogy also fit Stone. “He wanted to get to the truth,” says Zackary Sklar, a former editor at The Nation, who edited Garrison’s book and coscripted JFK. “He wanted to know who killed the president and why.” But, adds Sklar, “You don’t realize what you’re getting into.” Indeed, the world of conspiracy buffs is filled with contradictory information, turf wars, fringe operators, all of whom, it seemed, descended on Oliver Stone.

Seeking a toehold in the morass, Stone hired Jane Rusconi, two years out of Yale, as a research coordinator and built a library of practically every book and article ever written about the assassination. “Once we got to Dallas, my phone was ringing all day with people,” remembers Rusconi. Stone, meanwhile, was interviewing potential technical advisors. Among the first was renegade researcher Larry N. Howard, the founder and codirector of the oft-maligned JFK Assassination Information Center in Dallas’ West End Marketplace. When he heard about Stone’s movie, he fired off a fax: “John F. Kennedy was murdered by the people who controlled the real power base in the United States of America. In their minds he was a threat to ‘National Security’ and had to be eliminated.” Howard promised Stone sixteen revelations, from the identity of the assassin to the role of the Dallas police in the cover-up. A few days later, Stone phoned: “Come to California!” Sitting in Oliver Stone’s living room, Larry Howard let his theory rip.

“John F. Kennedy committed suicide, political suicide,” Howard told Stone. “He was getting out of Vietnam, getting rid of the Mafia, dumping Lyndon Johnson in 1964. He fired Allen Dulles from the CIA, said he was going to break up the CIA into a million pieces, make peace efforts with Castro and Khrushchev, sign the nuclear-test-ban treaty. Civil rights was going strong. He had Bobby to succeed him; he had Teddy after Bobby. So the real people who had the power in this country, the military-industrial complex, decided that Kennedy was soft on communism and was a threat to national security and worldwide peace. So they got rid of him through rogue elements of the CIA, with the Mafia as a junior partner. And from that point on, they covered it up from the top—the Warren Commission, which Johnson set up with Dulles on the panel.”

On a trip to Dallas to tour Howard’s center, Stone liked what he saw and hired the center for $80,000. Howard introduced the director to 21 people, including Marina Oswald, former Dallas district attorney Henry Wade, James Leavelle, and the ambulance driver who loaded Kennedy’s casket. When the director was ready to start filming, remembers Howard, he called Howard to his side. “He said, ‘This is a very historic film for a very historic event, and I want you to be with me when the first frame runs through the camera,’” says Howard.

Stone had more conspiracy researchers advise him as well. In Washington he met retired Air Force colonel Fletcher Prouty, 74, who was the chief of special operations for the joint staffs during the Kennedy years. Prouty provided support for clandestine CIA operations from 1955 to 1964. Now a consultant and author (The Secret Team: The CIA and Its Allies in Control of the United States and the World), Prouty says, “You ask two questions: Why was the president killed and who did it?” The why, Prouty told Stone, was Vietnam. He produced a declassified document that he helped draft, the last document pertaining to Vietnam that Kennedy signed before his death: National Security Action Memorandum 263. In 263, Kennedy directed the return of one thousand advisers from Vietnam by the end of 1963 and a complete withdrawal by the end of 1965. “That got him killed,” says Prouty.

“Who did it?” Prouty asks. “I would go to Lyndon Johnson for reference, when he said shortly before he died, ‘We had been operating a damned Murder, Inc.’ That’s an enormous statement coming from President Johnson. He was convinced that Oswald did not do it as an individual, that there was a conspiracy, and that the government had the capabilities to do it.” Prouty doesn’t believe that Johnson knew about the plot beforehand. “But afterwards, I think he knew.” Stone not only embraced Prouty’s Vietnam motive, but he also created a character, a Mr. X (Donald Sutherland), who tells Garrison in Washington the same thing Fletcher Prouty told Oliver Stone.

Back in Dallas, Stone hit the streets, immersing himself in the assassination. He met with intimates of Oswald, Ruby, and Ferrie. He met with right-wing Cubans, gunrunners, pilots, people who claimed to be the mysterious hoboes apprehended but never identified in Dealey Plaza. He met with people who urged him to fly to Cuba, where they could prove that Castro killed Kennedy. When he finished his research, Stone had his story. It would be a tale of three cities—the Garrison story in New Orleans, the Oswald story in Dallas, and the secret political story in Washington.

The Provocateur

Last January a new Oliver Stone production company set up shop at the venerable Stoneleigh Hotel, just a short drive from Dealey Plaza. It rented substantially discounted rooms on a floor that the old hotel had yet to refurbish, installed 21-line phones, and stocked cases of Evian water. The company had an intriguing and revealing name: Camelot Productions. But its project remained top secret until February, when leaflets were posted around town picturing Uncle Sam in his famous finger-pointing war pose beneath the words “We Want You! Open Auditions for Oliver Stone’s Next Film.” In addition to the usual cattle call—“Men With Texas Accents, Policeman Types, and Senior Cowboys”—was this line: “JFK Motorcade Look-a-likes.”

The turnout set a record for Dallas filmmaking. On February 16, 11,000 people packed the Dallas Convention Center, where Stone helped select the faces who would create his apocalypse for the sixties. Dallas actors were cast as Jack and Jackie Kennedy, John and Nellie Connally, as well as almost sixty other roles. Two thousand extras were hired at $40 a day, plus meals, to pack the parade route. Camelot paid the owners of two hundred sixties-era cars approximately $60 a day. Location directors secured thirty locations around town. The Venetian Room at the Fairmont Hotel became Jack Ruby’s Carousel Club; the same Oak Cliff boardinghouse where Oswald lived became Gary Oldman’s cinematic flophouse.

But what was in the script? Few people knew, except that it somehow involved the JFK assassination. Stone was being so tight-lipped about his story, which he called Project X, that everyone involved was required to sign a confidentiality agreement. Dallas was as excited as a starlet, so giddy over the prospects of stardom and at least $5 million for the local economy that she didn’t even ask about the role. Stone took cocktails at the homes of Trammell Crow and Clint Murchison III. He met the mayor at the Mansion on Turtle Creek and the Bunker Hunts at the Petroleum Club.

Oliver Stone was a hit with the new all-business Dallas. But to get what he wanted—to take over Dealey Plaza—he had to confront what he saw as the old self-conscious Dallas. “It doesn’t matter that we come into town and spend the money so people will have a job,” says Stone’s producer and facilitator, a Chinese immigrant named A. Kitman “Alex” Ho. “The only thing they care about is the sixth floor.”

Two months before the scheduled first day of shooting on April 15, Stone went before the board of the Dallas County Historical Foundation, which runs the assassination exhibit. Seeking permission to film on the sixth floor, Stone had laid the groundwork before his arrival, contributing $50,000 to the foundation. At the meeting, he said only once had he been asked for a script before getting permission to film at a location, and that was to use the Pentagon. But board chairman Lindalyn Adams was against Stone from the beginning. “My concern was that we had no idea what the script was going to be,” she says. “If we let that floor be used, that would be tantamount to condoning what the film would be about.”

In a Dallas Times Herald poll, readers voted three to two that Stone should be given access to the sixth floor. The vote by the historical foundation was closer—five to four—also in Stone’s favor. The battle, however, was not over. Stone still needed the approval of the Dallas County Commissioners’ Court, which not only had to ratify the move by the historical foundation but also controlled access to its headquarters—the old School Book Depository building.

Before the commissioners voted, Camelot’s location manager, Jeff Flach, handed over a $50,000 check as a sample of things to come. But Stone found a new antagonist in county judge Lee Jackson, a quiet, unassuming Republican with a strong sense of propriety. “I think it’s a tragic mistake to hang a For Rent sign on the sniper’s perch,” Jackson argued. He added that turning the seat of county government into a movie set for two months would be so disruptive that it would be hard for the commissioners to do their jobs. But Stone and his entourage were formidable lobbyists. “They are highly skilled at getting what they want,” says Jackson. “Their method is, at first, to describe a project as very simple. ‘It won’t really affect anyone too much, and this will be just fine, won’t it? And this won’t be a problem, will it?’ And then, three months later, what at first sounded like, perhaps, one camera from across the street, shooting from one hundred yards away, turns out to be occupying your building for two months.”

Backing Jackson was Martin Jurow, the producer or supervisor of more than fifty films, from Breakfast at Tiffany’s to Terms of Endearment, and a Dallas resident for twenty years. He was the executive producer of a ten-minute assassination film, narrated by Walter Cronkite, which runs on the sixth floor. Now in his seventies, Jurow spoke not as a film producer but as a concerned citizen. And he was concerned about turning over the sixth floor to Oliver Stone. “Some people are so beheaded by Hollywood glamour that they lose sight of their own mentality and morals,” he says today. He preached to the commissioners in a similar vein.

“No matter what is in that agreement, that contract means nothing,” Jurow told the commissioners’ court. “When a director like Oliver Stone comes in, he will brook no interference. And what I am deeply concerned about is something that no one has even mentioned. Who has read the script? . . . [People will say] you must have read the script before you gave him permission to go in and take over this entire building, this seat of government, this site of a memorial? . . . At least know what you’re getting into as far as what’s the story going to be. He’s no documentary filmmaker. He’s a challenger. He’s a provocateur.”

But Hollywood is hard to resist. After much debate, the commissioners gave Stone what he wanted: access to their building’s roof, lobby, exterior, jury room, parking lot, and a section of the county jail—even limited access to the sixth floor. The building’s window trim would be returned to its original orange. Its exact 1963 exterior would be recreated with theatrical scaffolding. Its walls and roof would be crowned with the original Texas School Book Depository signs. As rent, Camelot Productions would pay Dallas County nearly $84,000 for the right to use its building for nine weeks, including $15,000 for the seventh floor and rooftop, $4,350 a month for lost parking revenues, and $150 a day to use the exterior of the building. (Also 23 days worth of late charges were added for missing the May 14 deadline for restoring the building to its previous condition.) But the commissioners had one stipulation: They would be given a free prerelease preview of the film, at which time they would decide whether Dallas County would be given a credit—or a disclaimer.

“A Thousand and One Vultures”

“I’m fighting the battle of my life,” says Oliver Stone. He is sitting in a conference room at Lantana Center in Santa Monica, California. In the adjoining editing rooms, kids in jeans and JFK-theme T-shirts work frantically on 650,000 feet of film to give birth to JFK. The editing-room walls display an autographed portrait of a newly inaugurated Lyndon Johnson and an ancient panorama of Dealey Plaza, while film reels cover every inch of desk and floor.

Stone always looks haggard—his wrinkled white shirts, red socks, and harried demeanor have become part of his persona—but now the pressure is palpable. His brow is sweating. His eyes are red and glassy. His wispy black hair shows the effect of his hands having run though it. His entire being exudes exhaustion—the result of his year-long war with a hostile press, combative assassination buffs, and zealous defenders of the Warren Commission, all of whom have attempted to portray Oliver Stone as the biggest assassination buffoon since Jim Garrison. As Gary Oldman says, “This is not Home Alone.”

“There’s a thousand and one vultures out there,” groans Stone, “crouched on their rocks, saying, ‘Ah, here comes Stone.’ They want to come down and just peck out my eyes and rip my guts out. I’m such a target in a way, because I’ve attacked big things. And now I’ve got not only the usual Hollywood vultures on my tail, I’ve got a lot of the paid-off journalist hacks that are working on the East Coast with their recipied political theories, who resent the outsider, the rebel with a different theory.”

He leans back in his chair and stares. “Are you gonna attack me, Mark?” he asks. “Are you after me, Mark? . . . Is your editor cool? Is this gonna be a rip job on me?

“I think it’s pretty ugly,” he continues. “I think the press is motivated, in part, by fear. Fear of new facts. Or fear of a new spirit emerging about this Kennedy issue. There’s a desire to keep things covered up, to keep things hidden. And to scoff at Garrison is easy. But the Warren Commission is the official story, and the official myth, and its foundations, as painted by its apologists in the press, are tainted, deeply tainted. There’s too many loose screws in there.”

The attacks began last February, when Harold Weisberg, an assassination researcher and author, sent Stone a scathing letter. Calling Garrison’s investigation “a tragedy” and any film based on it “a travesty,” Weisberg wrote Stone, “As an investigator, Jim Garrison could not find a pubic hair in an overworked and undercleaned whorehouse at rush hour.” Weisberg says he didn’t receive a reply from Stone. But soon he knew plenty about the movie; somehow he obtained a first draft of the screenplay (now in its seventh draft) and sent it to his old friend George Lardner, Jr., who reports on national security issues for the Washington Post.

And on May 19 most of the Post’s Opinion section was filled with a story titled ON THE SET: DALLAS IN WONDERLAND: OLIVER STONE’S VERSION OF THE KENNEDY ASSASSINATION EXPLOITS THE EDGE OF PARANOIA. The story was illustrated with a cartoon of Stone framing a shot in JFK’s limousine, while Jack gets his face powdered and Jackie talks on a portable phone. Asking “Is this the Kennedy assassination or the Charge of the Light Brigade?” Lardner blasted everything in the script from the number of shots fired in Dealey Plaza to the sudden, mysterious death of David Ferrie (the early script had two Cubans forcing medicine down Ferrie’s throat, while Lardner, who claims to have interviewed Ferrie on the night of his death, concurs with the coroner’s ruling of natural causes) to Garrison’s courtroom summation (“It was a military-style ambush from start to finish, a coup d’état, with Lyndon Johnson waiting in the wings”). Stone says he threatened the Post with a lawsuit for copyright infringement. “They got a stolen screenplay, which they quoted from out of context and wrongly,” he says. “They diminished the commercial value of private enterprise.”

But what irritates Stone most is Lardner’s attack on his central thesis—the Vietnam war as motive. Wrote Lardner: “There was no abrupt change in Vietnam policy after JFK’s death.”

“Absolute horeshit,” says Stone. “From the get-go, Johnson, in NSAM 273, escalated the war in Vietnam by calling for covert warfare, which Kennedy never had.”

Stone brands Lardner “a committee journalist, a lethargic journalist” and accuses him of defending the CIA and the Warren Commission. Replies Lardner: “Is he still raising that junk? He doesn’t learn very good, does he? I got a correction in the New Orleans Times-Picayune [in which Stone called Lardner ‘a CIA agent journalist’]. Stone thinks any criticism of him must be part of a conspiracy. His complaints are not only groundless and paranoid, they smack of McCarthyism.”

Many other voices have reported from the Stone front. Rosemary James, formerly with New Orleans States-Item, covered the Clay Shaw trial and believed Garrison’s investigation to be a disgrace. (“Now comes a gullible from La-La Land who wants to regurgitate all that garbage.”) The Chicago Tribune noted that Warner Books, a division of Time-Warner, is paying Garrison $137,500 to reissue his book. (“Speaking of conspiracy theories, what are the odds that this transaction will influence Time magazine’s review of the book or movie, considering that Warner Bros. is distributing the film?”)

Stone counters with references to the CIA: “They bring down governments. This is their job. Why isn’t it conceivable that an outlaw organization such as the CIA that does this abroad would do it domestically?” Others support Stone by citing CIA document #1035-970, dated April 1, 1967, a month and a half after Garrison’s investigation was made public. The document advises how to combat critics of the Warren Commission: “. . . employ propaganda assets to answer and refute attacks of the critics. Book reviews and feature articles are particularly appropriate for this purpose.”

But if the CIA is so determined to suppress the truth, and if it could kill a president, then why would the agency allow a Hollywood director to expose its darkest deeds? “I got a lot of light on me,” he says. “To kill me would point the finger at something a little bizarre, wouldn’t it?”

He cradles his head in his hands. “They don’t kill you anymore,” he says. “They poison your food. You get sick. You don’t die. You get sick, and you get incapacitated for a year or two . . . and you get strychnine laced in your system. Or else they simply discredit you in the media, which is probably a more sophisticated way of doing it, like they did Garrison, you see. They just made fun of him. They ridicule you as a beast. As a monster. As a buffoon. And they do a good job of it. And the movie has to overcome.”

Stone had Camelot’s phones debugged in Dallas and Los Angeles. “No, we didn’t find anything,” he says. “But, of course, they’re into satellite taps now. You don’t have to go into the phone system.” Listening to Stone, one senses a trace of resignation. Could this be a retreat from the defiant anarchist who told the Los Angeles Times in late 1989, “The vandals are at the gate. We have a fascist security state running this country . . . Orwell did happen. But it’s so subtle that no one noticed. If I were George Bush, I’d shoot myself.”

Stone calls JFK “a potential minefield; I’ve bitten off a lot.” And so Oliver Stone is editing, which he calls the most intense experience of his career. “I wrote a lot of research material into the script, and I’m finding out the line as to what I can use and what I can’t use now,” he says. “I’m pulling out a lot of things that I felt would be in the movie. It’s always a painful retreat for me. I’m in my ‘Napoleon returns from Moscow’ phase, where I try to basically get out whole.”

But while Stone concedes that he doesn’t have all the answers, he won’t give an inch about the factual accuracy of JFK. Stone says his movie portrays history. “Oh, yeah,” he says. “I feel we’re very close. . . . I cannot include everything I would like to include. I don’t even use half of the incriminating evidence that we have, because of time. But I definitely feel that our film is close to the mood and texture of the time and to the true feelings of Oswald. We don’t come out with a strong who and how. What we come out with is a why. And I think we get very close to the truth of what really happened. The true inner workings.”

And what is the truth? “One would have to wonder about the behavior of the Dallas police that weekend,” says Stone. “Chief Curry’s and Will Fritz’s motivations are still highly questionable, as was Mayor Earle Cabell’s. I always found him to be rather strange. Especially his testimony right after the murder. Bland. Dismissive. He buys very quickly into the lone-nut assassination theory. And also you have to realize that he’s the brother of Charles Cabell of the CIA, who was a deputy chief to Allen Dulles, who hated Kennedy. You have H. L. Hunt’s bizarre behavior, leaving Dallas minutes, minutes, after the Kennedy assassination, as if it were a preplanned exit. As if. You have to wonder about them allowing Jack Ruby to be around all weekend like that. You have to wonder about the security on Lee Harvey Oswald, who had killed the president. Why was there no record of the investigation? Dallas police, as you know, at that time had a very shady reputation for corruption.”

Many of Stone’s revelations came in Dealey Plaza. “I discovered the true geography of the place,” he says. “I felt it. I smelled it. I felt the concept of echoes. I got a sense of how many shots could actually do it. I got a sense of the difficulty of shooting at Kennedy, at a moving target, handling a Mannlicher-Carcano in that environment. I saw the motorcade, reconstructed it. And I sensed the sheer pressure that the assassins must have been under—Oswald, if he in fact pulled the trigger, the difficulty of hitting somebody at that distance with that cheap shoulder weapon.”

Standing in Dealey Plaza, feeling, as he put it, “historic,” Stone says he received a sign that he was on the right track. “It was the second or third day we were shooting,” he says, “and a bunch of extras were on the sidewalk. And I’ll never forget—a seventh-floor window fell out. The whole window came down, heading for those extras. It would have really hurt someone, severed hands, killed people. And at the last second, a burst of wind came out of nowhere and carried the glass onto the intersection there, Houston and Main, where it smashed into a thousand pieces about ten feet from the nearest extra. And I felt very much at that moment that something, an overall force, wanted us to be there and wanted this thing to happen.”

No Ordinary Soldier

Oliver Stone heads into the editing room and tells a production assistant to screen a segment in which Jim Garrison, studying the Warren Commission report, flashes back to assorted assassination scenes, recreated by Stone in nostalgic black and white. The film rolls. And there’s Kevin Costner as the six-foot-six-inch Garrison, in a vest and sixties haircut—a protagonist, Stone describes, as someone who, although he loses the outward battle, wins his soul in the end. He is sitting alongside Sissy Spacek as his wife, Liz, who wears a bouffant hairdo and pearls, and their kids. It’s dinnertime at the Garrison home, and the menu is conspiracy.

“Honey, do you realize that Oswald was interrogated for twelve hours after the assassination, with no lawyers present, and, nobody, nobody, recorded a word of it?” asks Costner.

“Huh?” replies Spacek.

“I can’t believe it. Again and again, credible testimony is ignored. Leads are never followed up. Its conclusions are selective. There’s no index. It’s one of the sloppiest investigations I’ve ever seen. Dozens and dozens of witnesses in Dealey Plaza that day are saying they heard shots coming from the grassy knoll area in front of Kennedy and not the book depository behind him. But it’s all broken up and spread around, and you read it and the point gets lost.”

As the maid clears the dishes, Spacek says, “Honey, that was three years ago. We’ve tried so hard to put it out of our minds, and you just keep digging it up again. You’re the DA of New Orleans. Don’t you think the Kennedy assassination is a little bit out of your domain?”

But Costner presses on. Finally falling asleep after a night of reading the Warren Commission reports, he’s haunted by flashbacks. A Dallas policeman testifying about the hoboes, his badge glistening eerily. A witness recalling two men in uniform on the embankment, describing the commotion and a flash of light or smoke. . . . Costner bolts up in his bed, awakened by the myriad nightmares.

“Jim, you all right?” asks Spacek.

“Honey, it’s unbelievable!”

“What?”

“The whole thing. A lieutenant colonel testifies that Lee Oswald was given a Russian language exam, a Russian exam, as part of his Marine training only a few months before he defected to the Soviet Union.”

Spacek groans. “I can’t believe it! Honey, it’s four-thirty in the morning!”

“Do I have to spell it out for you?” rants Costner. “Lee Oswald was no ordinary soldier. He was probably in military intelligence. . . . That’s why he was trained in Russian. There’s no accident he’s in Russia.”

“Go back to sleep,” says Spacek.

“Goddammit,” snaps Costner. “I’ve been sleeping for three years.”

Costner doesn’t look like a man about to “win his soul.” Gone are his leading-man looks. His hair is a mess. His speech is babbling. Soon almost everyone will doubt him. And at this moment, he seems exactly like Oliver Stone.