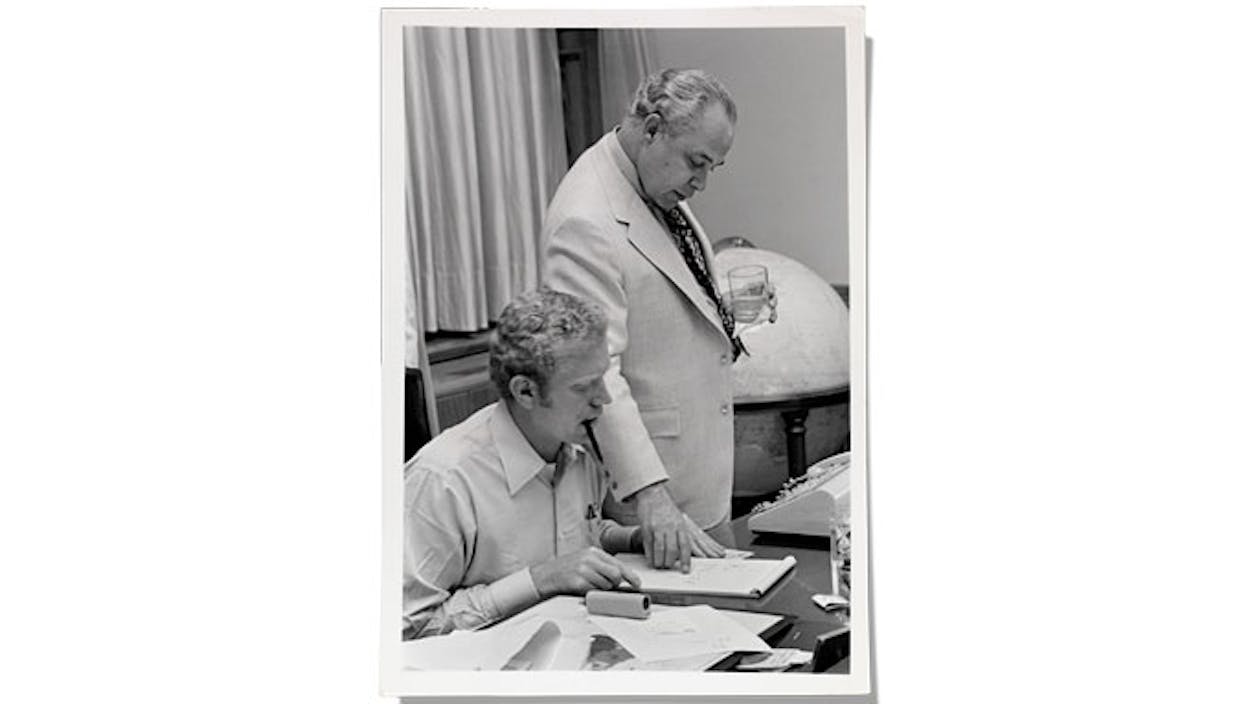

When the incomparable Washington power broker Robert Strauss died in March at the age of 95, the major obituaries trotted out the same stories about his sharp tongue and high self-regard that people had told for years. Like the one about the time he was serving as the administration’s special trade representative in the seventies and Jimmy Carter asked him if he would abide by a rule that members of the president’s staff fly coach instead of first class. “Mr. President,” said Strauss, “I intend to fly first class until they come up with something better than first class.” Or the time Strauss was asked why he had built such a beautiful pool in his Dallas backyard if he didn’t like to swim. “Well, at the end of a hard day at the office,” he replied, “I like to come home, sit out by the water, and say to myself, ‘Bob Strauss, you’re one rich son of a bitch.’ ” It’s no wonder those stories get told and retold: Texans have always celebrated politicians with a cutting sense of humor.

Austin attorney Larry Temple, who worked in Lyndon Johnson’s White House, describes Strauss as a person who knew how and when to be “effectively outrageous”—emphasis on “effectively.” “He was refreshingly open and refreshingly candid,” says Ben Barnes, the former lieutenant governor of Texas. “He knew when to take himself seriously and when not to, and that’s a big reason why he was able to get things done. He knew how to work with the press better than anyone. If a reporter called to get information from Strauss, Strauss ended up getting information out of him.”

But as his friends knew, there was a core of decency beneath Strauss’s salty mouth and pointed elbows. Barnes will tell you that on the night in 1972 when he lost the Democratic gubernatorial primary, Strauss, one of his key strategists, was the last person to leave his side. And a year later, when Strauss was the chairman of the Democratic National Committee and Watergate was at full boil, he phoned George H. W. Bush, the chairman of the Republican National Committee, and told him, “Hang in there. This has nothing to do with you; you’re a good man.”

Strauss’s death marked more than the passing of perhaps the state’s most powerful unelected pol; it marked the end of an era in Washington when people had adversaries but not enemies. Strauss, who no doubt learned how to ingratiate himself when he was growing up outside Abilene as the son of a German Jewish immigrant, knew how to work with both Ds and Rs. He was invited to the Reagan White House to offer his advice on the Iran-Contra scandal, which the president followed. Decades later, his fellow Texan George H. W. Bush would appoint Strauss to be the last U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union and the first to an independent Russia. “He was a man for all political seasons,” says Barnes. “And there’s no one left in Washington to pick up his legacy.”

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- Ben Barnes