The spring semester is always a whirlwind for Michael Westbrook and the Hardin-Jefferson High School band. Up until mid-March, this year was no different. The 54-year-old band director was busy preparing his students for regional concert and sight-reading competitions in April. He was also working with a smaller group of kids who were headed to Austin for prestigious state solo and small-ensemble contests in May.

The concert band was hard at work on three pieces, including one called Redemption, a sweeping, romantic composition that had brought Westbrook to tears the first time his students played it. “Whenever we would play a new piece of music, he’d tell us a little backstory on it, and sometimes he would get emotional,” said Abby Thomas, a senior band officer and a student of Westbrook’s since fourth grade. “We always said, if Westbrook cries, we’re all gonna cry.”

Hardin-Jefferson ISD is a small district of 2,300 students near Beaumont. Westbrook, who grew up in Nederland and graduated from Lamar University, had served as a band director in Hardin-Jefferson for thirteen years and had become a beloved—and indispensable—member of the community. Middle-school band director Marshall Swift, whom Westbrook hired for his first teaching job in 2017, considered him a mentor. “He taught me how to be kind and compassionate and how to take things in stride, even when it’s difficult,” he said.

Known as a patient but demanding leader, Westbrook had worked tirelessly to build the Big Blue Machine, as the HJHS band is known, into a regional powerhouse, earning top rankings in its division at regional and state marching and concert contests. He’d also reinvigorated the military marching tradition at HJHS—a once-common style of marching that is now kept alive mostly in East Texas. In 2019, just 66 out of 1,077 Texas high school bands marched military style.

Yet there was no way Westbrook could have been prepared for the disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Governor Abbott declared COVID-19 a statewide emergency on Friday, March 13. All school events were put on pause, and the following Monday, students were sent home. Parents and kids dropped by the band hall throughout the week to pick up instruments, but they didn’t linger. Westbrook, a notorious hugger, was careful to keep six feet away.

Westbrook scrambled to come up with plans for teaching music over the internet. He sent the students an upbeat Facebook video, reminding them to sign up for Google Classroom and to practice twenty to thirty minutes a day to “stay in shape with their chops.” He also urged them to be safe and wash their hands and ended by saying “I love you guys.”

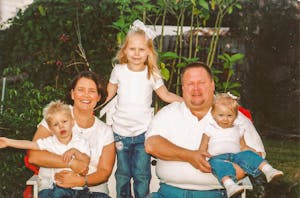

There weren’t yet any confirmed cases of COVID-19 in southeast Texas, and to many residents, the virus still seemed like a distant threat. But Karen Westbrook, Mike’s wife and a special education teacher in Lumberton, had been watching the news and was worried about her husband, who had diabetes and high blood pressure. She reminded their three teenagers—Mollie, Aaron, and Ella—to wash their hands. But Karen figured Mike was still too young to be in any grave danger.

On top of being a busy band director, Mike was also a professional trumpet player. He had been a core member of the Symphony of Southeast Texas for more than thirty years and was the bandleader for the Spindletop Brass Quintet. He also picked up work playing at churches and backing up headliners at casinos in Lake Charles, just across the state line. Karen didn’t worry much when he played a gig the day after Abbott’s declaration.

The weekend before stay-at-home orders were issued was, for many southeast Texans, the last blip of normalish life before months of lockdown. That Saturday, March 14, Mike Westbrook and his band, Eazy, played their monthly gig at Mackenzie’s Pub, a popular Beaumont bar and restaurant that features crawfish boils on Fridays (in season) and live music four nights a week.

Eazy was a big local draw, especially with older folks. Mike drove to the show with his next-door neighbor and close friend Kurt Killion, a former band director who played sax. Mark Saldaña, Eazy’s drummer, drove the two hours from his home in Lufkin for the gig, and lead singer Brad Fells, a Nederland resident, arrived wearing his trademark black shirt, red tie, and black cowboy hat. The four men had all grown up in Nederland and enjoyed catching up over beers between sets. Eazy, a ten-member horn band that specializes in what Killion described as “blue-eyed soul from the sixties and seventies,” played to a completely packed house, despite warnings about the coronavirus from local health departments. “Social distancing wasn’t here yet—the dance floor was full,” said Homer Pillsbury, a retired music booker and friend of the band who caught the last set that night. “It was a typical Eazy Saturday night,” said Fells. “Everyone was in great spirits.” The band closed down the house, and the musicians—and the pub’s patrons and employees—dispersed into the mild spring night.

The following Friday, March 20, after spending most of the week at school, Mike told Karen he was feeling off, but he was often tired from his busy schedule, so neither of them thought much about it. By Sunday, he was short of breath, and his temperature was over 101. By the time they arrived at the local urgent health clinic near their Lumberton home, his fever had climbed to 103. Mike tested negative for flu and strep but wasn’t tested for COVID-19. On Monday, his fever went up again, and Tylenol wasn’t helping. Karen borrowed a pulse oximeter from their neighbor, and Mike’s oxygen level was 88. She called the ER at Baptist Hospital in Beaumont to let them know they were on their way. The kids told their dad they loved him, and that they would see him soon.

The next day, Mike told Karen over the phone that he was feeling better. He’d been moved to his own room. His oxygen level was back up and his fever was down. He was being treated for pneumonia, though his doctor ordered a COVID-19 test. With his spirits up, Mike chatted on the phone so much with his friends, family, and colleagues that the nurses pleaded with him to save his breath. “I told him, ‘Don’t call me back, just rest and get your oxygen levels back up, text me if you need to,’” said Karen.

On Wednesday, things took a turn. Mike’s fever spiked to 103.7, and his breathing was labored. At 10 p.m., his doctor told Karen that Mike’s COVID-19 test was positive.

The next morning, his oxygen level dropped rapidly, and his organs began failing. He was put on a ventilator. The following day, March 26, he died. The hospital chaplain, who happened to be a friend of the family, was at Mike’s bedside at the end. It was the first COVID-19 death in southeast Texas.

Local news reporters started calling Karen, but she could barely comprehend what had happened, let alone talk to the media. How could her husband be gone? She began worrying that she’d caught the virus—they’d slept in the same bed as recently as Saturday night. What if she got sick and no one could help take care of her? What if the kids had it? Then there were the students and coworkers she and Mike had had contact with over the previous week, as well as his bandmates from the Mackenzie’s gig. Karen had lived her entire life in Lumberton and she and Mike knew almost everyone in town. She had no idea how far this thing might reach.

The Hardin County Health Department contacted Hardin-Jefferson High School on Thursday, hours before Mike died, to begin the process of contact tracing—interviewing people who had been around Mike over the past ten days or so, to gauge their level of exposure. According to Swift, it was a very thorough attempt to reach every student, parent, and teacher whom Mike may have come into contact with that last week he was at the school. Swift was most worried about that Monday, March 16, before the kids had been sent home. “I told them, ‘Pull our class rosters, pull our roll sheets, because that’s everybody who was at the band hall that day.’” The questions went on for several days. Everyone prayed that the virus had not spread.

It had spread, just not within Mike’s school community. Around the same time that Mike got sick, three other members of Eazy also came down with COVID-19. Killion, the 61-year-old sax player, began showing symptoms about five days after the show. His wife, Lisa (who was not at the gig), got sick a few days later. After hitting roadblocks in their attempts to get tested for COVID-19 (“We didn’t get a test until Mike passed, and all of sudden they were interested in us,” Killion told me), the couple decided to quarantine at home since their symptoms weren’t severe. (They both eventually tested positive.)

Fells, Eazy’s 65-year-old singer, spent two “miserable” nights in Baptist Hospital being treated for pneumonia and COVID-19. He responded well to the antibiotics and breathing treatments, though, and was sent home to quarantine. Fells’s girlfriend and his son, Bradley, who lives with him in Nederland, also caught mild cases of the virus from him, and have recovered.

While Killion and Fells and their families were relatively lucky, Saldaña, Eazy’s drummer, contracted a severe case of COVID-19. About a week after the Eazy show, Saldaña’s wife noticed he was having some breathing issues and took him to a Lufkin emergency room. The last thing Saldaña, a physician’s assistant, remembers clearly is walking into a COVID-19 testing tent; he has only vague recollections of being transported by helicopter from Lufkin to St. Luke’s Hospital, in Houston, and a faint memory of being sprinkled with holy water, which his sister had asked the medics to do. Saldaña spent more than a month unconscious on a ventilator and was released from rehab on May 16, in time for his sixtieth birthday. “The lights went out, and then thirty-something days later, I woke up,” he said. “It hit me like a freight train.” He still has months of outpatient rehab ahead of him, but he and his family consider his recovery a miracle; few COVID-19 patients survive being on a ventilator.

Around the time of Westbrook’s death and Saldaña’s life-flight to Houston, word started getting out about a cluster of cases many believed to be connected to that night at Mackenzie’s. Besides the four musicians, at least a dozen patrons also tested positive for the virus—though unofficial sources estimate it’s much higher than that. “We started looking into it and cases just started falling out of the walls,” the local health inspector told me. Vidor couple Mischelle and Danny Russell, both 68, were at the Eazy show with a bunch of friends. “I have a group photo of six of us from that night,” Mischelle told me on the phone. “Everyone in that picture tested positive.” Mischelle was able to recover at home, but Danny became critically ill and was transported by ambulance from Christus St. Elizabeth hospital, in Beaumont, to Houston, where he was part of a clinical trial for remdesivir at Memorial Hospital (he has since recovered). Other patrons’ symptoms ranged from mild to life-threatening; one Beaumont man in his seventies nearly died after being put on a ventilator.

Pillsbury, the music booker, woke up on Friday, March 20, with intense body aches and thought he had the flu. After a week-long ordeal of misdiagnosis, testing delays, and being sent home from the Baptist Hospital ER in the middle of the night, Pillsbury spent six nights at St. Elizabeth being treated for double pneumonia and COVID-19. As Pillsbury, 75, drifted in and out of consciousness in his hospital room, the lyrics to his old friend Leon Russell’s song “In the Hands of Angels” went through his head. When he went back home to recuperate, a friend called and told him about Mike Westbrook’s death and the other folks who’d gotten ill. Up until that point, he had no idea where he’d gotten sick. “I was there the night the coronavirus came to Beaumont,” Pillsbury said.

But, like everyone I spoke to, Pillsbury doesn’t blame Mackenzie’s. He was more upset that no one from the health department called him to follow up on his case and do contact tracing, even after he self-reported. “People who were there have a right to know what was happening, that they might have been infected,” said Pillsbury.

Pillsbury’s case wasn’t the only one that the health department didn’t trace to Mackenzie’s. Killion says that though he and Lisa were monitored by Hardin County and released from quarantine, they weren’t questioned about their comings and goings the week before they got sick. Fells was interviewed by the Jefferson County Health Department (“they did their job,” he said), but he said he was never asked about Mackenzie’s or his connection to Mike Westbrook. The Russells live in Orange County, but were monitored by the Hardin County Health Department; Mischelle told me no contact tracing was done, and she said that when she mentioned the Mackenzie’s connection to the health official, “They didn’t seem that interested.” Texas Monthly found at least eight cases that originated that night that were likely not connected to the expanding caseload.

Nearly four months after the Eazy show, no one from the Beaumont Health Department would go on the record, either about the number of cases officially connected to the night of March 14, or about the people who had apparently slipped through the contact-tracing cracks. It’s hard to blame the local health investigators too much: there aren’t enough of them to handle the growing COVID-19 caseload, and the contact tracing system currently in place doesn’t seem to be equipped to handle complex cases like Mackenzie’s, which is patronized by people from all over southeast Texas and parts of Louisiana.

Dr. Jana Winberg, health authority with the Hardin County Health Department, told me in an email in early May that when a case crosses county lines (southeast Texas alone comprises six counties), the individual departments work together to share information. “Sometimes we don’t know where someone lives until after we have called and asked the questions,” she said. Winberg also apologized for her delayed response, noting that her team had been working seven days a week to keep up with the workload. A health inspector who’s familiar with the Mackenzie’s case, but who asked not to be named, told me, “Basically, I’m exhausted.”

Public health experts warned even before the pandemic hit Texas that the state would need an army of contact tracers to handle COVID-19 cases. In late April Texas reportedly had around eight hundred working tracers; Governor Abbott pledged to increase that number to four thousand by June 1, but fell short of that goal by about a thousand. According to some experts, that’s a tenth of what’s needed: a model from George Washington University estimates that, based on the state’s caseload on July 6, Texas needs at least 30,000 contact tracers, or 106 tracers for every 100,000 people.

“The burden on the contact tracer is great,” said Elaine Symanski, an epidemiologist and professor at Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston. She told me that on average, for each person traced, contact tracers have to attempt to reach, and then follow, anywhere from fewer than five to upward of twenty contacts. Many people are reluctant to share personal information and the tracer must walk the line between being a medical detective and an empathetic social worker. “And you have to get them to answer the phone in the first place,” Symanski added. But none of the folks I interviewed seemed reluctant to talk to the health department, and most of them expressed surprise that they weren’t followed up with. “I was shocked,” Mischelle Russell told me. “No tracking whatsoever—it’s not what they said was supposed to happen.”

On Friday, June 26, as COVID-19 cases surged to record levels, Governor Abbott ordered all bars in the state closed and said in a TV interview that he regretted allowing them to reopen so quickly in the first place. The night before Abbott’s order, Mischelle and Danny Russell went back to Mackenzie’s for the first time since the Eazy show and danced to live country music. The atmosphere was a far cry from that boisterous evening when the patrons filled the dance floor, hugged on each other, and chatted with the band, but they were still glad to be out of the house. Assured by their doctors that they likely still have immunity and only a small chance of catching a serious case of the virus again, the Russells were willing to take a chance. Besides, Mischelle told me, they were being careful and responsible: “We wore masks on the dance floor,” she said.

In the days after Mike Westbrook’s death, at Karen’s lowest point, the tributes began pouring in on social media. Friends from every stage of his life—many of them members of his tight-knit Texas marching band community—shared their grief and their memories. “I just sat there for two days, watching Facebook, amazed,” said Karen. “How could I be married to this man for nineteen years and not know just how many lives he touched? The Sunday after he died, in the spirit of social distancing, students, friends, and neighbors planned to drive by the Westbrook home in a caravan, to pay their respects. So many cars showed up that the police had to handle the traffic.

Someone started a “Memories of Michael Westbrook” Facebook page; more than eight hundred people joined and began posting photos, funny stories, and testimonials to his musical talent, his propensity for telling corny jokes, his love of teaching, and his generosity. “Mr. Westbrook . . . basically raised me . . . Band was my home, my discipline, my goal, my challenge, my family,” one student wrote. “He was a parent to many of us, I can only hope I’m half as good a parent to my own daughter as he was to hundreds of us.” A trio of Mike’s best friends played a rendition of “On Eagles’ Wings,” on Facebook video, and a student created a polished, and very poignant, Mr. Westbrook tribute video and posted it on YouTube.

In early June Hardin-Jefferson High School held a graduation ceremony. Family members sat in the back area of the stadium and the seniors sat six feet apart in the front. There were no handshakes with the principal or hugs or even cap tosses. Restrained though the event may have been, it was at last a chance for the kids to pay tribute to Mr. Westbrook. Before the 175 graduates walked across the stage and received their diplomas, Abby Thomas, who was awarded the inaugural Mike Westbrook Memorial Scholarship and will go on to study nursing at East Texas Baptist University in the fall, played a saxophone duet with Adam Scott Borel, a fellow senior. When they were asked by their principal to perform something in Mr. Westbrook’s honor, the kids knew exactly what it would be: “It Is Well With My Soul,” their teacher’s favorite hymn. When the band was practicing an arrangement a couple of years ago, Westbrook had explained that the lyricist wrote the hymn in 1876, after his four young daughters died in a shipwreck. It’s a song, Westbrook said, about the unpredictability of life and how everything can change in an instant.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Health

- Longreads

- Beaumont