In the thirty years between 1984, when Greg Abbott graduated from law school, and 2014, when he became governor of Texas, he held four jobs: attorney, law professor, judge, and attorney general. From a young age, Abbott learned to think with a lawyer’s mind and speak with a lawyer’s tongue. His 2016 memoir Broken But Unbowed demonstrates just how important the law is to his personal and political identity. The book, one of those tomes intended to humanize and introduce its politician author to a wider audience, opens with the 1984 accident that left Abbott partially paralyzed when he was struck by a falling oak tree while jogging. But he then quickly moves on to the real subject: his legal career and his proposal to rewrite the U.S. Constitution.

By the time he became governor, he had little experience in the kind of transactional and relational politics inherent to his office. So in 2015, at the start of his first legislative session as the state’s chief executive, it was unclear what kind of governor he would be. Lawmakers got their first taste of Governor Abbott when they met with him early on in the session to discuss legislation. What were his priorities? What bills would he veto, and what legislation would he welcome? What did he need help with, and what could he offer in return?

Legislators soon discovered something remarkable. It was possible to stare the man in the eyes, to speak with him for a half hour or more and walk away with no better idea of where he stood on important legislative matters. He seemed unwilling to speak forthrightly about nearly anything, drawing a veil around his positions, lest he alienate some key legislator or interest group.

When Abbott did make himself clear, it was to issue marching orders or to punish politicians who had defied him. Some compared him, unfavorably, to former governor Rick Perry, who had a much more facile relationship with lawmakers of both parties. “[Abbott’s] concept of governing is ordering people around,” Republican state representative Sarah Davis of Houston told me in 2018. “He came into the regular session and kind of chided us, and then was absent for the rest of the session.”

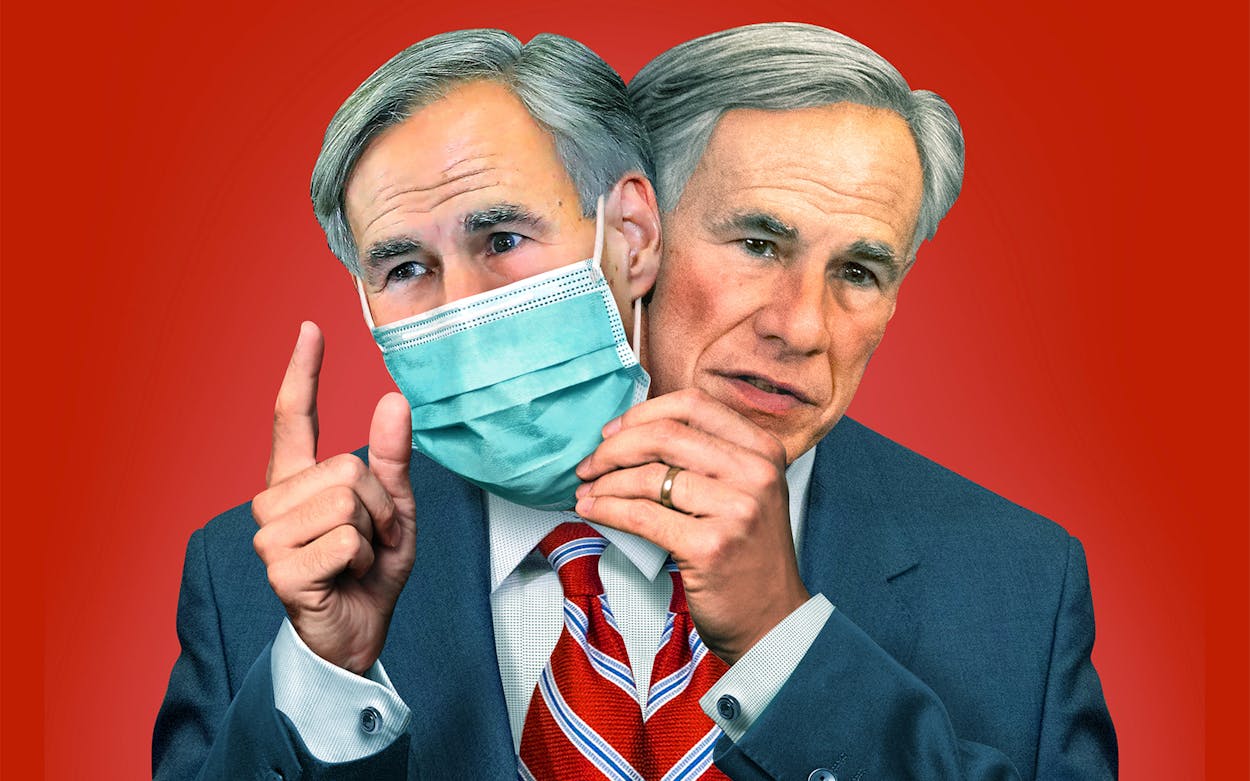

And his public statements often contradicted his private ones. Publicly Abbott endorsed the infamous anti-transgender “bathroom bill” in the 2017 session and pretended to advocate for its passage. But in private he reportedly reassured business groups—who worried the state would be boycotted by convention-goers and sports leagues from across the country—that the bill would never pass. Some speculated that Abbott was counting on House Speaker Joe Straus to take care of the problem.

In time, all kinds of Lege operators—Republicans, Democrats, lobbyists, politicians, advocates—came to share the view that the governor was both a cipher and a bully. Abbott only reinforced this perspective with his repeated attempts to take out Republicans who had crossed him in any way, from the moderate representative Lyle Larson of San Antonio to the right-wing representative Mike Lang of Granbury.

But if insiders came to think of Abbott as thin-skinned and vindictive, the public only saw a sphinx-like persona. Though he racked up very little in the way of achievements—his pre-K plan was greeted with indifference in the Legislature, and the brunt of his energy seemed to be reserved for minor items such as overturning municipal plastic bag bans—voters didn’t seem to care all that much. For Texans whose primary awareness of the governor came through softball interviews with local TV anchors, Abbott’s ability to remain broadly agreeable was, well, agreeable. But that was in the good times.

In 2020 Abbott has been presented with the most severe and sustained crisis of his five years as governor. Before the pandemic, he was able to duck the spotlight; now, its harsh glow follows him everywhere.

As of early August, Texas counted more than 8,000 COVID-19 fatalities of the 160,000 nationally, which has led some politicians in the state to boast about our low mortality rate. But the death toll is certain to grow, and it is most likely an undercount—first responders in Houston, for example, have reported a significant spike in people dying at home, many of whom are never tested for COVID-19. The model favored by the Trump administration, produced by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, now projects that some 25,000 Texans could be dead by November 1. We won’t know for a long time how many Texans the coronavirus killed, or what ill effects the disease has inflicted on the living. Recent evidence suggests some survivors are left with heart or brain damage.

But we know enough about what happened to make some broad judgments. There were two stages of Texas’s response to the virus. During the first, in March and April, Abbott issued increasingly strict responses to the pandemic, culminating in a statewide stay-at-home order on April 2. Texas was one of the last states to do so, but along with local shelter-at-home orders, the shutdown worked. It flattened the curve and saved lives.

By making enormous sacrifices, Texans had prevented the virus from running riot like it had in states such as New York. For the governor, this was an opportunity to gloat. On May 18 Abbott posted a meme on Twitter that compared the state’s low case count and its “morality [sic] rate” to those of New York and California, suggesting that Texas had cracked the code. If he had been the protagonist in an ancient Greek play, the tweet would have come with the sound of thunder: He had tempted the gods. And he would keep doing so.

Abbott rushed the reopening. Despite promising to listen to “doctors and data” and gradually lift restrictions, he started to reopen the economy at the end of April, when the pace of new infections and hospitalizations hadn’t really slowed. Everyone knew the restrictions would have to end, eventually. But the sacrifices made in the first stage were supposed to give leaders time to work out a plan for managing the pandemic. That planning never materialized. Instead, there was a long report issued by Abbott’s advisory council, made up mostly of wealthy donors to his campaign, on how Texas would “reopen” and return to economic normalcy. Abbott set a goal for testing—30,000 a day—that took weeks to achieve and still fell well short of what experts said was needed. The contact-tracing network the state put in place was laughably inadequate, beset by contracting scandals and staffed with a workforce that shrank as the virus grew.

By May, bars, gyms, hair salons, and movie theaters were welcoming back customers, many of them without masks. For a few weeks everything seemed okay, but the virus was silently at work. By June, new cases began to climb, and didn’t plateau until mid-July. By early August, when this story was written, more than one thousand Texans were dying a week, according to official figures.

How could things have gone so wrong? Texans are now discovering what lawmakers saw in Abbott during that first legislative session: an unwillingness to communicate clearly and a tendency to seek the most politically expedient position, particularly when confronted by the Republican Party’s right wing. Neither of those qualities is a good match for a public health crisis. As time goes on, the artifice is becoming more clear. Abbott’s approval numbers, though still far better than President Trump’s, have been falling, even as other governors have seen a surge of popularity during the crisis.

Let’s talk about four important instances in which Abbott, who did not respond to a request for comment, said one thing and then did the opposite—in the process making things so hopelessly confusing that no average Texan could be expected to know where he really stood or what the state was doing.

First: To mask or not to mask? On March 22 Abbott invited local elected officials to implement “more strict standards” than his own directives. Texas is a big state, after all, and it made sense for locals to make their own decisions, he said. Some mayors and county judges, including Harris County judge Lina Hidalgo, responded by requiring residents to wear masks in public. Hidalgo, in particular, became an immediate object of Republican anger. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick characterized her mask requirement as “the ultimate government overreach.”

On April 27 Abbott caved to the pressure from his right and forbade local officials, even in cities hardest hit by COVID-19, from enforcing mask requirements. He said he believed in “individual responsibility” instead of “government mandates.” When case numbers started to rise precipitously a few weeks after Abbott’s reopening, mayors and county judges again clamored for the authority to require masks. Abbott backtracked once more, this time in a way that left observers’ heads spinning. He hinted that there was a hidden clause, as yet undiscovered, in one of his executive orders that would allow local officials to put in place a mask mandate—a sort of riddle, one eventually solved by Bexar County judge Nelson Wolff. The governor seemed pleased, in the manner of a parent whose child has made it through an escape room. “The county judge finally figured that out,” he said. Turns out, Abbott had quietly left room for local officials to require businesses to require patrons to wear masks, instead of directly requiring the patrons to do so. And if that weren’t confusing enough, Abbott eventually changed his mind (again) and issued a quasi-statewide order on July 2, after two months of back-and-forth flip-flopping, mandating mask wearing in public in all counties with more than twenty active COVID-19 cases. (By early August, that included 147 of the state’s 254 counties.)

Second, there were the tight statewide restrictions that Abbott implemented on April 2, his most decisive action so far in fighting the virus. At the time, he stressed that his was not a shelter-in-place order, which he argued was a confusing and inexact “term of art,” as if he were trying to persuade a jury. For greater clarity, he called the plan the “Essential Services and Activities Protocols.” There was such confusion about what he had actually done that Abbott was compelled to later clarify that it was, in fact, a stay-at-home order.

Third, Abbott’s order expressly ordained that breaking the . . . ESAP? . . . could be punished with a fine or jail time. But then Dallas hairdresser Shelley Luther came along. After she reopened her salon in defiance of Abbott, Dallas authorities ordered her to close down. When she refused, the county judge fined her. Then, when she thumbed her nose at court orders, a judge sent her to jail, making her a cause célèbre for the right. In another remarkable sleight of hand, Abbott tried to deflect blame onto Dallas officials, studiously ignoring that his own executive order had set off the chain of events that led to Luther’s troubles. Once again bowing to pressure from his right flank, the governor retroactively nullified the penalties he had implemented a month before.

Fourth, because of the Luther fight, Abbott accelerated the reopening of some businesses, including bars and salons, even as COVID-19 cases were not yet on the decline. He had previously said that he would wait to see evidence that the first round of business openings hadn’t led to an uptick in the case counts before moving forward with the next phase. But amid the backlash from opponents of COVID-19 restrictions, he changed his mind.

Perhaps the most revealing test Abbott has faced recently involves the matter of the GOP state convention. The Republican Party of Texas had long planned to hold its biennial convention in mid-July in Houston, by then one of the nation’s most dangerous coronavirus hot spots. It would have brought some six thousand attendees, many of them older and especially vulnerable to the virus, from all around the state for a crowded three-day fete. An in-person convention was a virtual guarantee that some delegates and service workers would get infected and possibly die.

It was a bad idea that Abbott’s party nonetheless seemed hell-bent on pursuing. What did the governor have to say about it? Would he speak up, in an attempt to save the lives of his own party’s activists? “You’re the top Republican in the state, governor,” said an anchor for KDFW, in Dallas, on July 6, after Houston mayor Sylvester Turner begged the party to call off the gathering, before canceling it himself two days later. “What do you think should happen?”

The governor’s answer: “I know that the executive committee for the Republican Party of Texas have been talking about this. I think they continue to talk about it, and they weigh all of the consequences including the public health and safety measures, obviously . . . They’ll make a decision.”

The anchor persisted: “You don’t want to weigh in on what you think should happen?”

The governor paused and then gave his answer: “Obviously, I think whatever happens—whether it be, listen, this convention or any action that anybody takes—we’re at a time with the outbreak of the coronavirus where public safety needs to be a paramount concern, and make sure that whoever does anything and whatever they do, they need to do it in ways to reduce the spread of the coronavirus.”

Huh?

A day later, an anchor for KENS, in San Antonio, tried a different tack: “Will you be attending in person?” Abbott dissembled, so the anchor tried again. “Yeah, listen, as for myself, as well as for everybody else,” Abbott said, “we will continue to see what the standards are that will be issued by the [State Republican Executive Committee], by the state Republican Party to determine what the possibility will be for being able to attend.”

Not only was Abbott unwilling to say whether he thought the convention was a good idea, he couldn’t even say whether he would be there. The interview aired on the station’s five o’clock broadcast. Not half an hour later, the party’s executive director announced that elected officials would be delivering online messages instead of giving in-person speeches. Abbott surely knew this important fact when he was on the air.

It makes sense in many cases for a lawyer or a politician to maintain maximum ambiguity. The question of whether to go through with the convention was a divisive one in the party, particularly among skeptics of Abbott. But, again, it was an event that was likely going to sicken and maybe even kill loyal Republicans. What does it say that Abbott was unwilling to speak up—that he let Tur-ner take care of the problem for him?

Early in the pandemic, on March 11, Washington state governor Jay Inslee held a press conference to announce a ban on large gatherings. A reporter asked him if violators would face penalties. Inslee’s response: “The penalties are you might be killing your granddad if you don’t do it.”

That played in news broadcasts across the country. It summed up the nut of the problem before most Americans had started to wrap their heads around it. You might be fine, if you’re healthy and young, but there are those in your life who will probably not be fine if you contract the virus and spread it to them. It was also pithy, blunt, and a little confrontational. In other words, it was a Texan thing to say. You could see Rick Perry or Ann Richards or George W. on a good day saying something like it.

Texans profess to prefer outspoken and decisive politicians—mavericks, you might say—even when we don’t agree with them. Yet what we see in the news every day in Texas is the product of muddling through—a lawyer’s compromise. That’s why cities in the Rio Grande Valley and Houston are relying on mobile morgues while Abbott forbids local leaders from declaring a lockdown. It remains Abbott’s position that Texas can both “open up” and contain the virus. You don’t have to be an epidemiologist to know that this does not make an iota of sense. We have real-world examples now: in countries that acted aggressively to contain the virus, such as South Korea and the Czech Republic, normal life is returning. Containment must come before normalcy. When you try to have it both ways, you end up having neither.

When governments fail, leaders often reframe humiliating national setbacks as evidence of the indomitable spirit of its people: during World War II, British civilians were told to focus on the “miracle at Dunkirk” and not the reason why their army had to be evacuated from Dunkirk in the first place. As this wave of the coronavirus has appeared to slow, Abbott has presented it as a good news story, the achievement of plucky Texans working together. But he is responsible in great part for the wave itself.

The best we can hope for right now is that the virus’s rapid spread through the state dramatically slows and doesn’t return. Even if that happens, the calamitous surge of infections that has killed thousands of Texans and sickened hundreds of thousands more can be blamed in great part on decisions made by the governor—his unwillingness to allow mask mandates until very late in the game, his speedy opening of bars and other indoor businesses, his consistently confusing messaging. But he doesn’t seem to have learned anything. Schools are reopening without a robust plan to keep students, teachers, and families safe.

The United States, and Texas, decided not to make the tough choices required to contain the virus. As a result, normal life will not be resuming here for a long time. In June Abbott told a press conference that under his leadership Texas would find a way to “coexist with COVID-19,” as if the virus had sent us a cease and desist order. If only the world were a courtroom.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Greg Abbott