The calendar says it’s still 2019, but it sure feels like 2020 has already started in Texas. Nancy Pelosi is making frequent trips here to raise money, telling donors that “Texas is ground zero.” The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee has opened a Texas office for the first time in forever. Ted Cruz is issuing dire warnings about the prospect of Donald Trump losing Texas. And the president has made six visits to the Lone Star State in the past year alone.

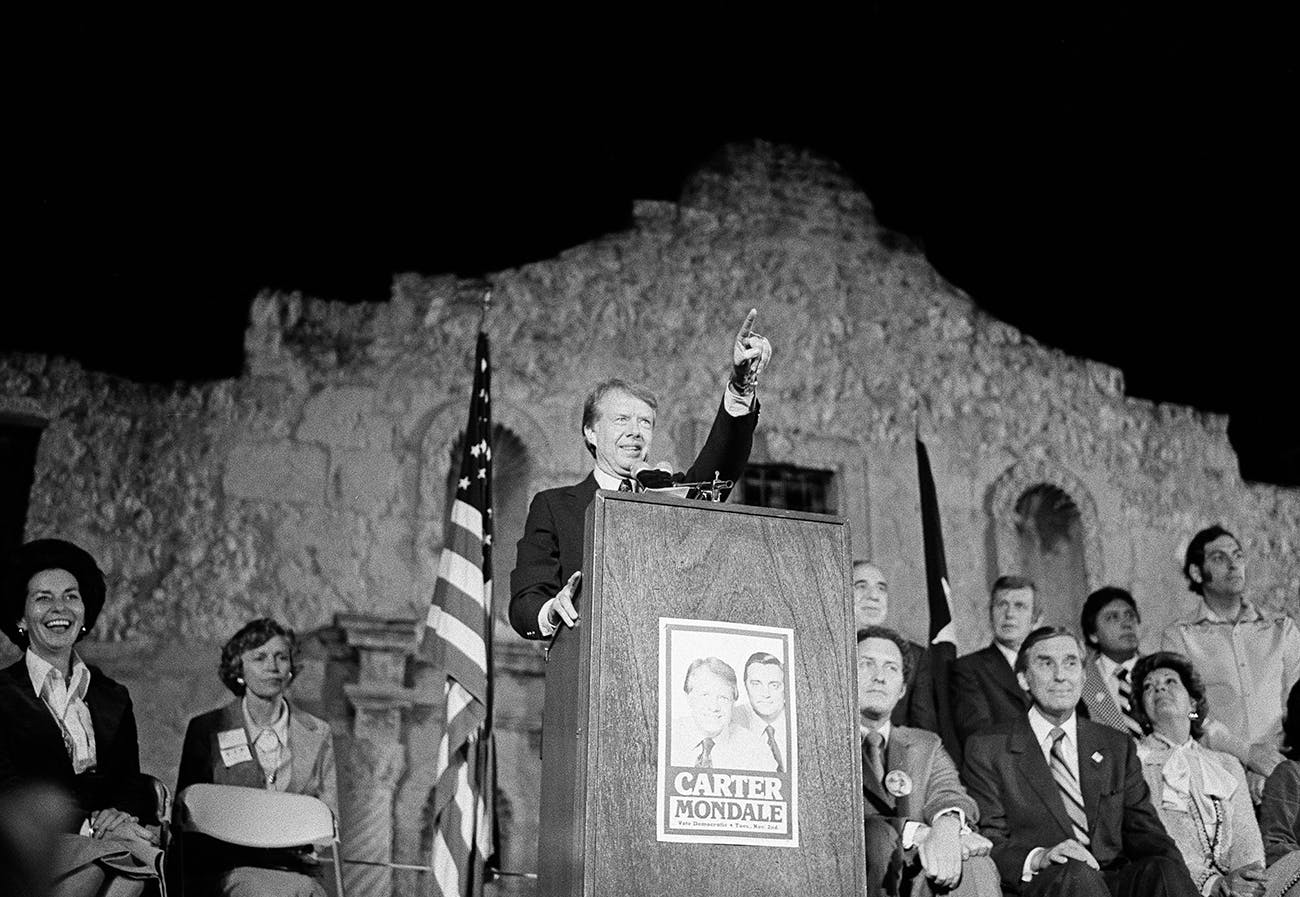

For decades, the top of the ballot has been sleepy in Texas. You know the drill: no Democrat has won statewide office in a quarter century, and the last Democratic presidential candidate to carry the state was Jimmy Carter, in 1976. An 18-year-old who cast her vote for Carter would be 61 today. She would have lived most of her adult life watching Texas become redder by the year. But things seem to be changing. If our Carter voter is still a Democrat, she may yet see Texas once again help put a member of her party into the White House. That would be an earthquake in American politics.

“If Texas turns back to a Democratic state, which it used to be, then we’ll never elect another Republican [president] in my lifetime,” John Cornyn said earlier this year. If you doubt that, consider this: if Hillary Clinton had carried Texas in 2016, she would have accumulated 270 electoral votes on election night—the exact minimum number needed to win. For Republicans, Texas is a presidential firewall, as important to their electoral math as California is to Democrats. For Democrats, the Lone Star State is the holy grail; unlocking the state’s 38 electoral college votes would likely mean decades of White House control. Even if Trump holds Texas, a close race could siphon gobs of money and energy from the president’s campaign in traditional swing states.

But it’s not just about the White House. Ten Democrats have announced that they are challenging Cornyn for his Senate seat. Six Republican-held seats in Congress are in play. If Democrats win all of them, they will have a majority in the 36-member Texas congressional delegation. In the state House, Democrats have a decent chance at picking up the nine seats they need to take control of the chamber. Doing so would give them greater influence in redistricting when new congressional and legislative maps are redrawn, a process that will profoundly shape the political agenda of the state through 2031.

In short, there’s a hell of a lot riding on November 3, 2020. And if you’re paying any attention to this election, you’ve probably heard that the other side is gunning for you and everything you hold dear.

But perhaps you’re skeptical of the hype. After all, both sides have an interest in making the election seem competitive; doing so gooses turnout and fund-raising. And maybe you recall all the other times you’ve heard this likely story. For many years, Democrats have promised a comeback, only to fizzle out. In 2013, for example, an Obama-affiliated group, Battleground Texas, breezed into the state promising to break the Republican grip, only to watch its top candidate, Wendy Davis, lose to Governor Greg Abbott by twenty percentage points. Even Beto O’Rourke, whose near-defeat of Ted Cruz in the 2018 Senate race alarmed a lot of conservatives, couldn’t close the gap. And though Hillary Clinton (Hillary!) came within a relatively respectable nine points of Trump in 2016, she still lost.

So when you hear Pelosi, Cruz, and Cornyn contemplating a political transformation in the Lone Star State, one question likely comes to mind: Can Texas really turn blue in 2020?

Well, maybe. Both Democrats and Republicans have a case to make for why they’ll win in Texas—and what winning even looks like. (Again, it’s not all about the presidency.) So as the calendar flips to 2020 and this wild, wild election year gets fully underway, let’s take a closer look at each side’s game plan. Remember: only the fate of the nation hangs in the balance.

2020 Is the Year Texas Turns Blue (Finally)

The case for Texas turning blue in 2020 begins with this: Texas is already a light shade of purple and getting purpler with each passing day. In 2018, angered by Trump and thrilled by the O’Rourke campaign, a newly mobilized Democratic coalition of young people, suburban women, and minorities voted in record numbers. At the top of the ballot, O’Rourke came within 2.6 points of defeating Cruz—a jolt of adrenaline for the moribund Texas left. Two Texas Republican congressmen were ousted, five others came close to losing, and two state Senate seats flipped to blue. Perhaps more consequential in the long run: Democrats made big gains in almost all of the state’s major cities and suburbs. The results showed that the GOP juggernaut was no longer invincible.

A big part of the Texas Democratic party’s game plan for 2020 is to convince national party leaders that Texas, not Ohio, should be the party’s battleground state. Manny Garcia, the state party’s executive director, pointed me to a 2017 Mother Jones article that laid out the case. Ohio is 80 percent Anglo, with an aging population. Texas is just 44 percent Anglo, and the majority of its citizens are age 34 or younger. In Ohio, the Democratic presidential nominees have done successively worse over the past two elections. In Texas, Barack Obama lost to Mitt Romney by sixteen percentage points in 2012; Clinton narrowed the gap to nine in 2016. “Maybe you think Ohio is more winnable than Texas,” Garcia said, quoting the article, “but would you bet your party’s future on it?”

Austin-based Republican data expert Derek Ryan said that his party should be concerned by the fact that a million first-time voters turned out in November 2018. More than two thirds registered after the 2016 presidential election, and three quarters were under the age of fifty. “It’s kind of opened Democrats’ eyes, that ‘If I do go out and vote, and all of my friends who aren’t voting show up, then maybe we do have a chance at turning Texas purple or blue,’ ” Ryan told me.

As Elizabeth Warren might say, Texas Democrats have a plan for that. The party is mounting a drive to push those energized voters back to the polls while also recruiting more new voters. In a sharp break with past strategy, the plan does not count on getting a lot of older, white voters to switch their allegiance back to Democrats. Instead, the party will focus on registering 2.6 million people identified as likely Democrats. Garcia said the starting point was the 1.8 million people who registered to vote in Texas between the 2014 election and 2018. “That’s like the entire voting age population of New Mexico,” he said. “The majority were women. The majority, people of color.”

The turnout drive will be buoyed by unusually intense campaigning for congressional seats. The national Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee is putting organizers on the ground in Texas, with the express aim of defending two seats the Democrats picked up in Houston and Dallas in 2018, and to target six other districts held by Republicans. And if the 2018 congressional races are any indication, the parties will spend more than $50 million on voter drives and TV advertising in these districts.

Democrats may also be able to count on some crossover conservatives. As many as 400,000 Republicans cast ballots for O’Rourke and for the Democratic candidates in the contests for lieutenant governor and Texas attorney general. In all three races, the Republican candidates were men who practiced Trump-like divisive politics. That could spell trouble for Trump himself, who received only 52 percent of Texas’s vote in 2016, the lowest total for a Republican presidential candidate since Bob Dole, in 1996, when Ross Perot played spoiler. And Trump’s weak performance came before the impeachment hearings, trade wars, and inhumane migrant detention centers.

But probably no factor works more in the favor of the 2020 Democrats than a sense that they can actually win. Don’t underestimate the psychological advantage in politics, particularly when the grassroots share the enthusiasm of political elites.

“What the Democrats in Texas needed more than anything else, more than good candidates, more than a lot of money, was to believe again that we could win, so that people would get off their asses and go register people to vote and go knock on doors,” said Democratic consultant Colin Strother. “For a generation, we didn’t think we could win, so we didn’t try.”

No, Texas Won’t Be Turning Blue in 2020

For those who aren’t Trump fans, this all sounds great. But left-leaning Texans have comforted themselves with just-so stories many times. You’ve no doubt heard the one about the growing Hispanic population magically leading the party out of the political wilderness—only for Democrats to be disappointed by anemic turnout and the affinity many Texas Latinos, especially men, have for conservative social policies. And Republicans still have huge institutional advantages.

Texas Christian University political scientist Emily M. Farris told me she believes the idea that Democrats could turn Texas blue is a “dream.” The Texas “baseline partisan identity is still Republican,” she said. Simply put, Texas has more conservatives than liberals. In 2016, exit polls showed that 44 percent of Texas voters called themselves conservatives, while only 20 percent described themselves as liberal. And even though Gallup found that roughly half of Texans self-identify as Republicans and half as Democrats, Republicans have been much more successful at mobilizing their older, whiter constituency. It’s simply harder for Democrats to get their base, which tends to be younger and less white, to come to the polls.

Minority Report

Even though the number of registered Texas voters with Hispanic surnames increased by 240,000 between 2016 and 2018, the Hispanic portion of the electorate stayed the same: 19 percent.

The Democrats may also find ways to alienate some voters they need. In contrast to O’Rourke’s feel-good Senate campaign, which was heavy on charisma and light on policy, the Democratic presidential race is leaning heavily into pleasing the party’s progressive base. That may make sense in the primary, but unless the eventual nominee convincingly pivots to the center on some issues, he or she could push crossover voters to return to Trump.

“There’s an opportunity for the Republican ticket to improve its performance in the suburbs because it’s going to be a choice between Trump” and the Democratic nominee, said Republican political consultant Matt Mackowiak.

Another reality is that the 2018 election wasn’t as much of a “blue wave” as it first appeared. Though O’Rourke benefited from plenty of crossover voters, most of them then voted for Governor Greg Abbott and other down-ballot Republicans. Even Texas’s buffoonish agriculture commissioner Sid Miller received more actual votes than O’Rourke. Mackowiak argues that without an unusually popular candidate like O’Rourke on the Democratic ticket, those Republicans will return to their conservative comfort zone in 2020.

“The central question really is, was 2018 the beginning of a trend or was it a one-off?” said Mackowiak. “My view is 2018 was a hundred-year flood in Texas.”

Steve Munisteri, a former Republican Party of Texas chairman who now advises Cornyn’s reelection campaign, isn’t quite as cocky as Mackowiak. He told me that Texas isn’t as red as many people believe, pointing to how the state’s most populous urban and suburban counties have trended or turned blue over the past decade or so, starting with Dallas County, in 2006. “When you start losing the major urban areas, that’s the canary in the coal mine,” he said. Even so, he still gives the GOP the edge, at least in 2020.

The name of the game for both parties will be—you guessed it—turnout. Munisteri predicts there will be 10.5 to 11 million voters in 2020, a record. (About 9 million Texans voted in 2016.) Democrats can count on about 4 million votes, while Republicans can count on about 4.5 million. “First party to five and a half million wins,” Munisteri said. Either side can get there, but Democrats face a tougher task.

To go the distance, Republicans are cranking up their own voter registration and get-out-the-vote operations. Munisteri said the state party has identified 1.5 million unregistered voters who are likely Republicans. And a group of wealthy Republicans is putting at least $10 million into a drive called Engage Texas to target unregistered people who live in reliably Republican areas. Such efforts are unusual; Texas Republicans typically rely on motivating their sizable base rather than chasing new voters.

The conservative case for why the GOP will continue to run Texas comes down to this: the state is becoming increasingly competitive, but Democrats are foolish to think the parties have reached parity. Republicans will win in 2020 because they still have the numbers.

It’s a powerful argument, and one with plenty of empirical evidence. But even if Trump wins Texas, victory could come at a terrible cost, and not just in terms of collateral damage to his allies in Congress and the statehouse. For decades, the GOP presidential nominee has been able to take Texas for granted. Not so this time. Trump may have to spend heavily, in time and money, to ensure a win here. That’s time and money he won’t have in swing states that he must also hold to win reelection, such as Michigan and Wisconsin. Even if Texas goes for Trump in 2020, a competitive race here could cost him the election.

This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “How to Win Texas in 2020.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Donald Trump