This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I had been in some strange places and listened to some strange stories, but none of them had been as bizarre as this.

“Neither of us slept very well the night before the assassination,” she said, snubbing out one cigarette and lighting another. “He kept tossing and turning, and finally I asked him how he could go through with it. He said, ‘Honey, it’s like war. The president is a national security threat. If I don’t do it, we’ll be in a nuclear war very soon.’ ‘But he’s got two children,’ I told him, ‘just like you.’ But he said, ‘Honey, matters were taken out of our hands a long time ago.’ Then he turned over and pretended to be sleeping, and I started to cry. . . .”

We were seated in the living room of Geneva White Galle’s modest home in Odessa, and she was telling me how her late husband, Roscoe Anthony White, killed President John F. Kennedy. The story was shot full of contradictions and wildly implausible coincidences—if this had been a book I would have thrown it away after page one—and yet there was something interesting in the way she told the story. Like the heroine of a soap opera, she was able to weave the most intimate details of history into the fabric of everyday life and make it sound, well, not exactly believable, but compelling.

I already knew that at least two parts of the story were true. First, Roscoe White was in the same military division as Lee Harvey Oswald—the 1st Marine Air Wing. So were about seven thousand other Marines. Geneva swears that her husband and Oswald were friends, but except for her word, there is no proof they even knew each other. Second, in the fall of 1963, Roscoe White was a Dallas policeman, and Geneva worked for a few weeks as a hostess in Jack Ruby’s Carousel Club. Geneva’s story is that she overheard her husband and Ruby plotting to kill the president and that when Ruby caught her listening outside his office door, he threatened to torture and kill her two children, Tony and Ricky. Rock White, as Roscoe was called, suggested an alternative: that she agree to undergo a series of shock treatments, calculated to obliterate her memory. Starting in 1964 Geneva submitted to four separate sets of shock therapy. The final treatment was in 1975, four years after Rock White was killed in a mysterious explosion.

“Rock looked like a whipped dog when he went to work that morning,” she continued. “He didn’t touch his breakfast. I was bathing the kids when I heard on the TV that Kennedy had been shot. Then they said that a policeman had been shot, and I thought, ‘Oh God, it’s Rock!’ But then he came home around seven, just like always. I put the kids to bed about nine and made a pot of coffee, and we sat in the kitchen, talking for a long time. He said, ‘Honey, I never dreamed it would come to this.’ ”

She stopped, as though that were the end of the episode and began shuffling around the room, pointing to paintings, woven baskets, and ceramic figures that she had created. They overwhelmed the tiny room. “I play the piano too,” Geneva told me. “Or used to when I felt better.” The cord of her oxygen breathing tube trailed behind, and from time to time she pressed the nostril piece tight, making little rattling noises as she inhaled. She told me that she was dying, and ticked off a list of diseases faster than I could take notes—diabetes, lupus, emphysema, cancer of the intestine, several others. “I shouldn’t smoke like I do,” she said, reaching for another one. Geneva had shown me photographs of herself when she was in her early twenties, including one in which Jack Ruby is leering as she lifts her mini-skirt. She was a real looker 27 years ago. Apparently her life had been a chapter from hell.

“The assassination,” I reminded Geneva. “You were about to tell me what happened on Saturday.”

“Sunday was Ricky’s third birthday,” she said, picking up the story line, “so on Saturday I baked a coconut cake and got the party favors ready. That night Ruby came over for supper. We sent the kids outside to play with Ruby’s dog . . . what was her name? . . . Sheba or something like that. Rock cooked steaks on the grill, and I made baked potatoes and a salad and strawberry shortcake—that was Rock’s favorite. After dinner I was washing the dishes, and I heard them talking in the living room. Ruby was bragging about killing Kennedy, flying high like he was drunk, only he wasn’t drinking. He talked about killing Oswald the next day and said it wasn’t going to be any problem because he’d get a signal when they were ready to move him. He said something about the magic bullet, how one of them had left the magic bullet at Parkland—”

“He used that term—‘magic bullet’?” I interrupted. The phrase wasn’t even coined until after the Warren Commission report declared that the bullet found on a stretcher at Parkland Hospital was the same bullet that passed through the bodies of both Kennedy and John Connally—a truly remarkable conclusion because the bullet would have had to travel through seven layers of skin, shatter one of John Connally’s ribs, shatter a bone in Connally’s wrist, and emerge in nearly pristine condition. Magic was the only word to describe such a bullet. “Are you sure they said magic bullet?” I asked Geneva again.

“I’m positive.”

“Mama, that can’t be right,” her son Ricky interrupted. In the four and a half years since he had read his father’s amazing confession in an old journal he had found in a footlocker, Ricky White had become familiar with the details of the assassination.

“I get confused,” Geneva admitted. “It’s been a long time.”

Roscoe White’s journal is no longer available for our inspection—Ricky says the FBI took it—but let’s accept it on faith for the moment. The journal was an interesting mix of the familiar, the convenient, and the ludicrous: It must have read like a C-grade movie script, and yet it was a scenario that nearly every critic of the Warren Commission wanted to believe. As Ricky recalls, the entry for November 22, 1963, started like this: “I was Mandarin, the man behind the stockade fence who fired two shots. Lebanon was the man in the Book Depository who fired two shots. Saul was the man in the Records Building who fired two shots.” Oswald wasn’t mentioned by name, but apparently he was the patsy, not one of the shooters. Mandarin’s spot behind the stockade fence at the crest of the grassy knoll would have been the perfect position for a sniper. From that vantage point a marksman could have picked off the president with a pistol.

Though the Warren Commission maintained that no shots came from the grassy knoll, dozens of eyewitnesses thought otherwise. So did Sheriff Bill Decker, and so did a number of Dallas policemen, who rushed up the hill immediately after the shots were fired. Almost all of the doctors who worked on the president at Parkland thought the head wound indicated a shot from the front.

It is anomalies like these that keep the mystery of the assassination alive—and have brought the otherwise unremarkable American Gothic family of Roscoe and Geneva White into the public light.

A Lean-Mouthed Marine

Who was Roscoe White, and what was there about his life that made anyone suspect he was an assassin in the employ of some renegade intelligence organization? For one thing, he fit the profile. He grew up on a farm outside the small town of Foreman, Arkansas, a model boy who loved football, God, and country, who did what he was told and didn’t ask questions. The speech that Roscoe White made to his graduation class at Foreman High School, warning of the international communist conspiracy and advocating a strong national defense, was a remarkable declaration of patriotic fervor, touching in its innocence but unquestionably sincere. This was a young man waiting to be molded, prepared to make any sacrifice in the cause of the Cold War.

After graduation, Rock worked in his grandfather’s sawmill in East Texas. “He was lean-mouthed,” recalls Kenny Slagle, who worked with him. “He didn’t say much about his personal life. But he was a worker. We worked on Saturday without any kind of supervision, stacking lumber until it was stacked right.” At 21, Rock married Geneva Toland, who was just 15. A year later he joined the Marines.

In August 1957 he sailed aboard the U.S.S. Bexar, from San Diego to Yokosuka, Japan. One of his shipmates was Lee Harvey Oswald. For the next five and a half months, White and Oswald were assigned to the 1st Marine Air Wing, first at Atsugi, Japan, and later at Subic Bay, in the Philippines. Oswald was a radar operator in Marine Air Group 16. The two groups may have been quartered miles apart, but Oswald and White probably drank at the same enlisted-men’s club. Being Texans a long way from home, there’s a good chance the two met. Atsugi, incidentally, was one of the bases from which the CIA operated its ultrasecret U-2 reconnaissance flights.

In 1959 White reenlisted for six years but inexplicably changed his mind in 1962 and applied for a hardship discharge. In the meantime, Oswald had also received a hardship discharge, had defected to Russia for 31 months, and then was allowed to return to the United States without so much as a debriefing by U.S. intelligence. Oswald’s odyssey stretched credulity beyond all reason: Many of his Marine buddies just assumed that Oswald was an American intelligence agent. Early in 1963, Roscoe White moved his family to the Oak Cliff section of Dallas, where Lee Harvey Oswald was living.

Geneva White remembers her husband’s talking about a friend from the Marine Corps named Lee, particularly a story of how Lee got drunk one night and kept falling down a flight of stairs. Among the memorabilia that Rock brought home after his discharge was a photograph of a group of Marines waiting to board a ship in the Philippines: Oswald is clearly identifiable in the foreground, and Geneva says that the Marine in the background whose face is shaded by the bill of his cap is her husband. The same photograph, cropped differently, was published in Life magazine three months after the assassination. Another souvenir was a .22-caliber two-shot derringer. Geneva remembers that Rock told her, “Keep this in a safe place. It’ll be worth a lot of money some day.” The derringer is similar to the one that fell out of Oswald’s barracks locker in 1958, wounding him in the arm.

Geneva recalls being introduced to Lee Oswald a few months before the assassination at a rifle range near the Grand Prairie Naval Air Station, where White and Oswald were practicing marksmanship. A few weeks later, she saw Oswald in a grocery store near their home in Oak Cliff. “I saw your friend Lee today,” she told Rock, who became irritated and told her to never mention that name again. About the same time, Geneva caught her husband in bed with a woman named Hazel, an act of infidelity that severely strained their marriage. Rock promised that the affair was over, Geneva recalled, but when she happened to overhear Jack Ruby mention Hazel’s name one night at the Carousel, she stopped outside the door of his office and eavesdropped. She heard Ruby tell her husband: “Hazel is the contact.” Ruby said something about the Bay of Pigs and how Kennedy had betrayed them. The longer she listened, Geneva said, the clearer it became that her husband and Ruby were talking about killing the president. This, at least, is the memory of a dying woman with a history of shock treatments.

Policemen who worked with Rock White find the mere suggestion that he was involved in the assassination ludicrous. “Let me put it this way,” said W. L. Barnard, now retired from the Dallas Police Department. “Roscoe was one hundred percent jarhead Marine, just like me, trained to follow orders. Now do you suppose a man like that would kill the Commander in Chief of the United States of America?” John T. Williams, another former Dallas policeman, said, “The whole story is unbelievable. Rock never told anyone that he was personally acquainted with Oswald or knew anything about the assassination.” White quit the police force in October 1965—two years to the day after he signed on—telling fellow officers he was quitting because of financial and marital problems.

In the six years that followed, Rock White made a number of unexplained trips to New Orleans and other places. “I was never sure what was happening,” Geneva says, “but I was raised to let the man do the thinking and not ask questions.” In 1968 White moved his family to Mountain Home, Arkansas, supposedly to work for the post office. But nobody at the Mountain Home post office remembers him, and postal employment records don’t go back that far. Later that same year the family returned to Dallas, and White became the assistant manager of a five-and-dime store in Richardson.

“The family appeared to have money,” recalled the Reverend Jack Shaw, who was their pastor at Central Park Baptist Church. “New car, new home. As I recall, Roscoe pledged ten thousand dollars to our building program.” White’s sons, Ricky and Tony, had new bicycles and go-carts, and the family purchased a cabin on a lake in Central Texas. Rock continued to mess around with other women, and Jack Shaw counseled the couple and prayed with them on several occasions. “Rock poured his heart out to me,” Shaw said. “He told me he had sinned against God, his country, and especially against his wife. He told me he had taken human life on foreign soil and here at home. I knew he had been in the service and had been a policeman, and I didn’t press him for details.”

In the summer of 1971, shortly after Geneva returned from a trip to New Orleans, she suffered an emotional breakdown and was hospitalized for about a month. Jack Shaw was surprised that the family hadn’t sought his spiritual guidance but sensed that there was some reason for their reluctance. Years later he learned that on the trip to New Orleans, a strange and sinister man had approached Geneva in a nightclub, reminded her about Rock’s part in the Kennedy assassination, and told her: “We have another job for Rock. Tell him he has forty-eight hours to get in touch.” Apparently White never got in touch with the man.

By this time White had a better-paying job at M&M Equipment Company. But in September he was fatally burned when a leak in an acetylene torch flamed up, causing a can of chemicals that was stored under his workbench to explode. On his deathbed White told Jack Shaw that the explosion was no accident. Shaw assumed there would be a criminal investigation, but there wasn’t. White’s family eventually reached an out-of-court settlement with the chemical manufacturer for $57,000.

Not long after that, Geneva and her two sons moved back to her parents’ home in Paris, where she remarried. Jack Shaw didn’t see or hear from her again for nearly twenty years.

The Footlocker

Ricky White bounced along like an overgrown puppy, leading a film crew to the shed behind his grandparents’ home in Paris. “People don’t realize it yet,” he said, opening the door and pointing to the place where he had found the footlocker that had contained his father’s journal, “but this is a hysterical location.” Ricky sometimes got his words mixed up, saying “hysterical” when he meant “historical” and talking about how things were “unnormal” or “obvient” (obvious).

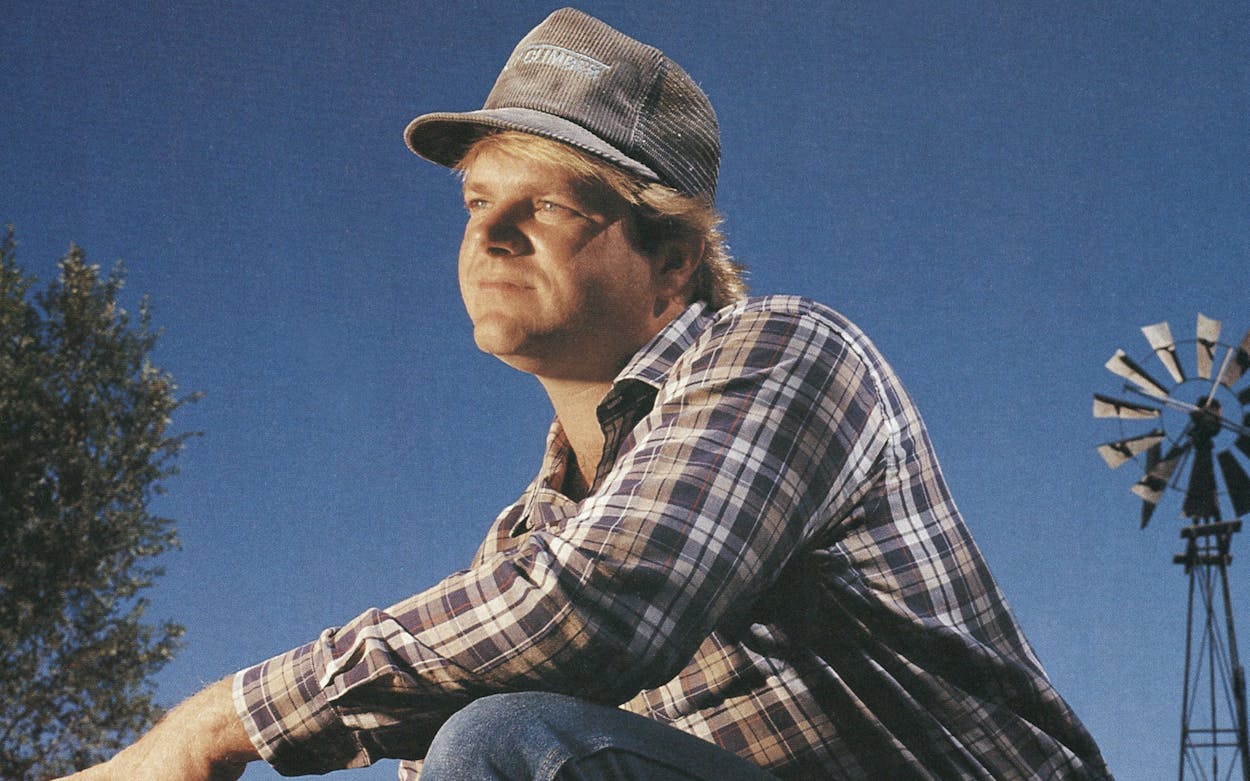

There was a shaggy, good-natured innocence about Ricky White, a bubbalike quality that made you want to pat him on the head. He had been a football player and a vocational agriculture student at Paris High; he still raised pigs, chickens, and geese at his rural home outside of Midland. His standard dress was boots, jeans, and a grimy oil-field gimme cap that he wore night and day—indoors and out—pulled down around his ears so that tufts of cream-colored hair splayed around the brim like spaghetti. It was always “yes, sir” this and “no, ma’am” that with Ricky. Though he was nearly thirty, older people invariably called him the kid or the boy. When someone asked a question that required coupling two or more independent thoughts, the look of bewilderment that shadowed Ricky’s face was truly childlike. If the Roscoe White story was a hoax, I decided early on, Ricky was its victim, not its perpetrator. He no more could have invented or even acted out a hoax of this sophistication than he could have explained the universe.

By the late summer of 1990, Ricky had become a minor celebrity. The print media had pretty much dismissed the story after a few days, but Ricky was in demand as a guest on talk shows, at civic club luncheons, and in college classes. A British producer named Nigel Turner had brought a film crew from New York to document the story, and American producers were sending out feelers. In public appearances Ricky was always escorted by one of the founders of the JFK Assassination Information Center in Dallas, who booked his appearances and screened the tips and leads sparked by the Roscoe White story. All this exposure couldn’t have been easy on the family of Roscoe White, this constant demand that they acknowledge that a beloved father-husband-brother committed one of the most heinous crimes in history. Yet in some curious way the family seemed proud of Roscoe’s accomplishments, or at least reconciled to them. “I think he was the Oliver North of his time,” said Roscoe’s sister, Linda Wells. “He was just doing what he thought was best for our country.”

Ricky didn’t just find his role as minor celebrity altogether distasteful, even though it caused some dissension within the family. His wife, Tricia, complained that when Ricky was invited to New York to appear on the Morton Downey television show, she didn’t get to go. “I was there the day we found the journal,” she said, “but nobody ever asks me about it.” Ricky tried hard to placate Tricia, but privately he believed she was being unreasonable. “It wasn’t her daddy that killed Kennedy,” he said. Geneva was also a problem, but for the moment she seemed content to let Ricky do the talking. But the story always went back to Geneva. She was the validator, the institutional memory. She was the one who said that Rock knew Oswald. She was the source of the stories about Jack Ruby. Everything that Ricky and Tony knew about their father and about Dallas and the strange happenings of 1963 came from Geneva. Even the journal had her fingerprint in that she was the only one who could vouch for its authenticity.

Ricky and other members of the family discovered the footlocker in 1982, on the day of Geneva’s father’s funeral. It contained not only the journal but also Roscoe White’s service record and other memorabilia, including an unmarked safe-deposit-box key and what appeared to be a receipt for $100,000 in negotiable bonds. Ricky took the contents of the footlocker to his home in Midland and puzzled over them for months. He studied photographs from his father’s military days and read bits and pieces from the journal, trying to grasp a father who had died before Ricky had a chance to know him.

For reasons that Ricky is still at a loss to explain, almost four years passed before he got around to reading Roscoe White’s journal entry for November 22, 1963. Stunned by what he had read, Ricky drove to his mother’s house in Odessa and showed Geneva the passage dealing with the assassination. “She read for a few minutes and started crying,” Ricky said. “Then she told me it was all true.”

Maybe Geneva planted the idea in his head—or maybe it got there by itself—but Ricky was overwhelmed by the belief that his father had meant for him to find the journal, that it was some kind of message from the grave. The journal seemed to him the centerpiece of a puzzle, extending back . . . he tried to remember how far. The mystery must have started, Ricky recalled, after his father’s death, when an old family friend appeared at their home in Paris with a mysterious packet of photographs. The family friend—let’s call him Bill X—had been hiding the packet for Roscoe, or at least that’s what Geneva led her children to believe. Then she locked the packet in a cabinet in her bedroom and allowed no one to see it.

As a teenager, Ricky knew only that the photographs seemed important. One day when Geneva was away from the house, Ricky and his friend Lance Nicholson forced open the cabinet and looked at the aging photographs. They were surprised and a little disappointed to discover that this secret treasure was nothing more than pictures of people, places, and physical evidence connected with the assassination of President Kennedy. Included in the forty photographs were a picture of Oswald’s naked body on a morgue slab; numerous photos of Oswald’s personal possessions, including selective service and Marine service cards issued to Alek Hidell, Oswald’s alias; and a variation of the famous photograph of a smirking Oswald posing in a back yard with a rifle, a side arm, and copies of communist newspapers.

There should have been no mystery concerning the origin of these photographs. On the day of the assassination Roscoe White had been assigned to the identification bureau of the Dallas Police Department and had no doubt copied the pictures from the evidence file, as had other policemen. But that explanation didn’t satisfy—or even occur to—Ricky White. Nor did it explain why his parents put such a high value on the photographs or why Bill X, who had known Geneva before she met Rock, had kept them until Rock’s death.

A few months after Ricky first viewed the photographs, something else happened that deepened the enigma. Two men broke into the White home in Paris, beat up Geneva, and took, among other things, the packet of pictures. The men were arrested a few days later in Florida on an unrelated charge, and FBI agents sent the pictures to Washington, where they were turned over to the Senate Intelligence Committee, which was investigating the government’s relations with the intelligence community. The packet was eventually returned to Geneva, but the mystery didn’t end there. In December 1976, staff members from the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) showed up at Geneva’s home in Paris and again collected the packet of photographs and other items of potential evidence, including a rifle stock that had belonged to Roscoe White. Shortly before the HSCA report was issued in 1979, the old family friend Bill X approached Ricky outside a grocery store in Paris and told him confidentially that the report would name his father as one of the conspirators. People in Paris believed that the mysterious Bill X was a former agent with Navy intelligence, though there was no proof. At any rate his story turned out to have no credibility, and Ricky forgot the incident—until the night he read his father’s journal entry for November 22, 1963.

In the weeks that followed, Ricky spoke of the journal to several close friends and acquaintances, but none of them actually saw the book. The only people who say they have seen the journal are Ricky, his mother, his wife, and a woman named Denise Carter, who read parts of the journal while babysitting with Ricky and Tricia’s two children. Ricky also told some of his story to Midland district attorney Al Schorre: He wanted Schorre to give him legal advice and to help locate the bank that went with the safe-deposit-box key from the footlocker. Schorre’s chief investigator, J. D. Luckie, made several trips to Dallas but couldn’t find the bank. In the meantime, Schorre told the FBI what Ricky had told him.

In January 1988 two FBI agents hauled Ricky and the contents of the footlocker to their office in downtown Midland and questioned him for five hours, copying some of the material and making an impression of the safe-deposit-box key. All of his belongings were returned, but later that same day one of the agents came again to Ricky’s house, supposedly to retrieve a notebook he had accidentally placed with the other material. A couple of days later, Ricky and Tricia discovered the journal was missing. Agents of the FBI categorically deny that they saw—much less that they stole—Roscoe White’s journal.

It was only after the journal vanished that the story took on commercial possibilities. Ricky was working for the Orkin Exterminating Company at the time, and he enlisted the support of a fellow worker, Andy Burke. The two of them began investigating the journal’s allegations and interviewing people who had known Roscoe White. Burke, who had a flair for promotion, convinced Ricky and his family that the story was worth a lot of money and attempted to line up writers, publishers, and film producers. In July 1989 Ricky and Andy even took a trip to New York and spoke to an editor at Viking Penguin. But publishers weren’t interested: Without the journal Ricky had nothing to sell. Obviously Ricky and Andy needed to do a lot more research. But research was expensive and time-consuming, and neither could afford to quit his job. On top of everything else, the effort of trying to prove that his father was a ruthless killer was putting an enormous emotional strain on Ricky White, who began to wonder if he really wanted to know the truth. Meanwhile, Geneva, who faced staggering medical bills and was several months behind in her house payments, lined up her own writer—a professor at the community college—and began to dictate her story. By this time Ricky was so distraught that he spoke of taking all the evidence he had collected and burning it. Geneva suggested that he simply bury it in the same coffin that she soon expected to occupy.

In January 1989 Geneva, Ricky, and Tony agreed to act in concert. The instrument that brought the White family together was an offer from a consortium of Midland oil men who agreed to fund the research in return for a share of any profits that might be forthcoming. Incorporated under the name of Matsu, the consortium retained a literary agent from San Antonio and searched for a writer in Dallas to draft a synopsis. Later, members of the consortium bought out Andy Burke’s interest for $16,000. But the problem was the same as it had always been: There was still no hard evidence to support the story, nor did anyone in the group know how to go about gathering evidence. By the spring of 1990 many of the investors were beginning to have serious doubts.

In desperation, Ricky went to see Larry Harris, a freedom of information officer for the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service in Dallas and coauthor of a book on the assassination titled Cover-up. Ricky and Andy Burke had talked to Harris on four previous occasions, without really explaining what they had in mind. “Burke had done most of the talking,” Harris recalled. “All Ricky had told me was that his father used to be a Dallas policeman, and he was trying to gather information about his life. But this time he came out with it. He said in this real low voice, ‘Larry, I think my father was one of the men who killed President Kennedy.’”

Harris, who had spent fifteen years investigating the assassination, was impressed by Ricky’s sincerity and by his obvious emotional dilemma. As it happened, Harris and Gary Shaw, a Cleburne architect and coauthor of Cover-up, had just opened the JFK Assassination Information Center in Dallas. The center was conceived as a project to educate the public about the mysteries of what its founders regarded as the greatest unsolved murder in the nation’s history, and to analyze data and act as a clearinghouse for new tips and leads. Shaw and a third partner, a builder-developer named Larry Howard, set up shop on the third floor of the West End Marketplace, an old warehouse converted into a shopping mall three blocks north of Dealey Plaza.

In the spring of 1990 Ricky White and the JFK center seemed a match made in heaven.

Exposing the Antichrist

The exterior of the JFK center’s three thousand square feet of exhibition and office space has the macabre facade of a wax museum. On one side of the entrance, video highlights of the assassination run continuously from eleven in the morning until ten at night, and on the other side life-size photographs of Ruby and Oswald loom like giant ogres. Above the picture of Oswald, in large letters, is the famous quote—and the center’s central message—“No, sir, I didn’t kill anybody. I’m just a patsy.” On another wall, above a montage a photographs, is an equally interesting quote, this one from New Orleans crime boss Carlos Marcello, who was singled out as a prime suspect in the assassination by the House Select Committee: “Three can keep a secret if two of them are dead.” Marcello is said to have this exact quote on his office wall.

There was a quixotic quality about Shaw and his partners that was both a necessity to the center’s operation and a detriment to its survival. Shaw and Larry Howard had quit lucrative professions to work full-time at the center. One or both were usually there seven days a week, answering phone calls and dealing with people who walked in from the mall with tales to tell or questions. Gary Shaw, who had been investigating the assassination for 26 years, was a mild-mannered, thoughtful man, well respected among assassination researchers for his knowledge and for his ability to keep the peace among rival factions. Like other disciples of assassination-conspiracy theory, they accepted that the Warren Commission was the Antichrist. Beyond that, the scenerio was anyone’s guess. The problem was separating the nut from the shell, and in an environment in which the nuts tended to predominate, the pitfalls were deep and treacherous.

The partners wanted to believe the Roscoe White story, wanted it too much. It was their hottest lead since the House Select Committee issued its report eleven years ago, and it fit nicely with their need to establish that the fatal head shot came from the grassy knoll. They recognized the potential for fraud—indeed, paranoia ran shoulder deep at the JFK center—but they made themselves believe that the story would rise or fall on its own merits. Ricky volunteered to take a lie detector test—which he passed—and agreed to turn over all his father’s papers to the center. If the partners had stuck to their original plan—to keep this new batch of evidence to themselves until it could be either proved or disproved—the story might have had a happier ending. But three months into the investigation, fearful that the FBI might swoop down and confiscate the evidence—or that one of their sources might compromise it—they decided to go public long before they had the story nailed down.

Once that happened, the center was flooded with calls and letters, some of them intriguing, most of them crazy or pathetic, few of them apparently helpful. An ex-Marine and soldier of fortune named Gerry Patrick Hemming remembered that on a trip to Dallas in 1963 to raise money for Cuban exiles, he met Roscoe White, who tried to sell him some rifles. A woman who didn’t sign her name wrote that she believed her husband was part of Roscoe White’s assassination squad. Another woman from Fort Ord, California, wrote that Henry Kissinger had arranged Kennedy’s murder to avenge an insult and that he kept the dead president’s brain pickled in a jar in his basement. Gary Shaw and I actually flew to a large Midwestern city to interview a man who claimed that the assassination plan used to kill JFK was the same plan he had drawn in 1954 to kill Harry Truman. After listening to the man for three hours, I was convinced that his was the most stupid, simpleminded, and outrageous concoction I had ever heard. But Gary Shaw wasn’t so sure. “Why would he lie?” Gary asked. That was a question I couldn’t answer. Maybe the man thought he could sell the story as a book or a movie plot. Maybe the telling had made him feel important. Maybe he was lonely.

In retrospect, I believe Gary Shaw’s real mistake was in not keeping the Roscoe White story within the confines of his own organization. At the last minute, Shaw decided to include on the investigative team an outsider, a Houston private investigator named Joe H. West, who had been working with Shaw on other aspects of the assassination. Shaw’s partners didn’t trust West. They saw him as reckless, comically secretive, and self-aggrandizing—a buffoon who unfailingly introduced himself as “a certified legal investigator licensed by the State of Texas,” as though that were something truly special. West had approached Shaw two years ago and declared that he wanted to spend the remaining days of his life solving what he regarded as the greatest mystery of all time. “I gave him some leads to follow, and he did a pretty good job,” Shaw said. “He tracked down a Mafia hit man who claimed that he had delivered some stolen rifles to Jack Ruby a few weeks before the assassination.” In the spring of 1990 Shaw convinced his partners that the team needed a man as aggressive and innovative as Joe West, a decision they would soon regret.

West almost immediately justified Gary Shaw’s faith, however. The team was having problems with Geneva: She seemed confused about the events of 1963. West decided to solicit the help of the Reverend Jack Shaw (no relation to Gary), who had counseled Geneva through many emotional problems and who had been at Roscoe White’s side when he died. When Ricky and Andy Burke called on Jack Shaw months earlier, Shaw had refused to help, but the minister was impressed with Joe West’s credentials and agreed to join the team. Shaw’s ministry had greatly expanded in twenty years. He now operated the Marketplace Christian Network in Plano and counseled members of the flock at a fee of $100 an hour. West himself was a former minister, and the two men formed an instant bond.

A few days later Jack Shaw flew to Odessa for a reunion with his onetime parishioner. While other team members waited outside, Shaw began to talk to Geneva and regain her confidence. Eventually, he would record more than forty hours of interviews, but that day after only a few hours he achieved a partial breakthrough. “Oh, my God!” Geneva called out suddenly. “I can’t believe I’m remembering that!” and she began talking about her trip to New Orleans and the sinister man who had approached her. Geneva thought that the name of the man she met in New Orleans was Netti, or something similar. Joe West assembled eleven photographs and asked Geneva if any of them was the man she remembered. She selected a picture of Charles Nicoletti, a gangland enforcer who was a key man in the CIA-Mafia plots to kill Castro.

There was a major development in the investigation in early June when Ricky recalled that the journal spoke of a witness-elimination program and hinted that the material from the footlocker contained other clues. One inexplicable item discovered in the footlocker was a paper sack containing some strips of cedar bark. Ricky—and later Geneva and Tony—remembered that Rock had buried a box near a large cedar tree beside their lake cabin. That had to be it . . . the message from the grave.

On June 6 the team located the cabin, now deserted, and for three days proceeded to dig up the back yard, first with shovels and picks and finally with a backhoe. But they found nothing. Bitterly disappointed, they returned to Gary Shaw’s home in Cleburne to regroup. As Ricky was driving back to Midland, he stopped in Ranger to buy gas and telephone his wife, who told him that his mother had been trying to reach him. Geneva had found another clue. On the inside of the paper sack that had contained the cedar bark, she discovered a barely legible notation, some Roman numerals similar to a house framer’s code and in even smaller print the word “Paris.” “I think your daddy was telling us there’s something hidden in your grandparents’ old house,” Geneva said. Ricky turned around and drove east to Paris.

The Ghoulish Green Book

It was late that night by the time Ricky reached the old house, which had been partially destroyed by fire. After breaking the lock on the front door, he searched the house by flashlight, first the downstairs and then the attic. Behind a piece of plywood he saw a heavy aluminum canister, sealed tight. “My heart was beating something awful,” Ricky recalled. “I’m a pretty stout old boy, but I had to use a crowbar to pry it open.”

What he found were his father’s Marine Corps dog tags, negatives of old family photographs, a faded green textbook with newspaper pictures pasted over the pages, and three cables covered in protective plastic. The cables professed to be orders from Naval intelligence, addressed to Mandarin, using Roscoe White’s serial number. A cable dated October 1963 instructed Mandarin that his next assignment was “to eliminate a national security threat to worldwide peace.” At the bottom of the cables was the code name RE-rifle, which was strikingly similar to ZR/RIFLE, an ultrasecret CIA project during the Kennedy administration to recruit assassins to murder foreign leaders.

The green book, or the witness-elimination book, as it came to be called, frightened Ricky White more than all the other pieces of evidence put together. Though the contents of the book hardly supported such a conclusion, Ricky saw it as proof that his father had murdered repeatedly. This was some sort of ghoulish scrapbook, apparently compiled at random and embellished with numerical code and hieroglyphics. Inside the front cover was his father’s name and serial number, and the words “players or witnesses.” Pasted to each page were old newspaper photographs. Some were easily identifiable—Ruby, Oswald, Jack and Robert Kennedy—but others were faces without names. One of the more obscure faces turned out to be the late Perry Raymond Russo, who once testified that he had attended a meeting in New Orleans where the plot to assassinate President Kennedy had been discussed; also in attendance was Lee Harvey Oswald. Written below the picture were the words, “Big Mouth you talked after all.”

On another page was a copy of the famous Mary Moorman photograph, taken at the instant the president’s head was blown open. An X drawn across a spot behind the stockade fence marked the place where Mandarin would have stood. Below the picture were these words: “Mandarin kills K uses 7.65 mauser in assassination.” For three days after the assassination, the Dallas police, the district attorney, and even the CIA believed the murder weapon was a Mauser. One of the pieces of evidence that Ricky turned over to the research team was his father’s 7.65 Mauser.

The contents of the canister stunned Ricky White. It was nearly a week before he told any member of the team what he had discovered, and even then he didn’t mention the green book. But Joe West seemed to know that Ricky was hiding something. West confronted Ricky one night after they had interviewed an old friend of Roscoe’s. Ricky remembers feeling emotionally overwhelmed and on the verge of tears. At that moment, he decided to show West the canister and its contents—all except the green book—and to give it to West for safekeeping. But rather than share this new evidence with other members of the team, West took it to Houston and locked it in his safe-deposit box. He eventually supplied the others with copies of the cables, but the originals remained locked in his bank box until Matsu filed a lawsuit. West countersued, charging that he had been libeled and his life had been threatened.

When Gary Shaw discovered that his partners had been right all along, that Joe West was a loose cannon, he terminated his relationship with the Houston investigator. But it was too late. Joe West—and his new associate, the Reverend Jack Shaw—were pursuing a separate investigation. Apparently West had appointed himself custodian of the evidence. Gary Shaw and his partners had Ricky and the green book, but West had the cables. And even more important, with Jack Shaw on his team, West had Geneva.

“One Hell of a Woman”

From the start the team had worked too slowly for Joe West’s taste, not being aggressive enough with potential witnesses and missing what he regarded as obvious clues. West outraged Ricky by claiming that Roscoe White’s old friend Bill X was a member of the assassination squad. Shaw and his partners worried that West would compromise their investigation and maybe subject the JFK center to a slander suit. Such petty considerations did not bother Joe West, who vowed he would pursue Kennedy’s killer until his dying day. “Like a mighty army marching across the land,” West proclaimed, “when justice is done, that will be my payday.”

From his Mafia informant, who told him that five Mafia big shots were in Dallas on the day of the assassination, West had already extrapolated another gunman on the grassy knoll. Even before Geneva identified Charles Nicoletti as the man she had met in New Orleans, West had come to the conclusion that Nicoletti was one of the Kennedy assassins. On May 11 he called a press conference in Galveston to make this startling announcement. But this was just a warm-up for the big event.

In mid-September 1990 West sent out press releases announcing another press conference and hinting that at long last he was about to produce the smoking gun. It seemed that a second Roscoe White journal had surfaced. Geneva had found it two weeks earlier, found it quite by coincidence when she happened to knock over a book titled Presidents of the United States. It was hidden under “Kennedy, John F.” Funny, Geneva hadn’t mentioned it to me, though I had interviewed her at her home just a few days after this astonishing discovery. She hadn’t even mentioned it to the other members of her family. Instead, she had turned the journal over to Jack Shaw and Joe West. And though it wasn’t exactly a quid pro quo, she simultaneously received a payment of $5,300, part of it a gift from the film producer Oliver Stone and the remainder from Jack Shaw’s ministry.

Standing with his back to a banner proclaiming “Truth, Inc.,” West told several dozen reporters that he was only a certified legal investigator licensed by the State of Texas—not a documents expert—so he couldn’t vouch for the authenticity of this new piece of evidence. But the fact that he had gone to all this trouble to make it public suggested otherwise. The night before the press conference, Jack Shaw had spoken of this breakthrough as “one of the most historically important events of the twentieth century.” Apparently Shaw changed his mind, because the next morning he pleaded with West to postpone the announcement until experts could examine the document. But West’s mind was made up, and wild mustangs couldn’t have dragged him off the rostrum. Halfway through the press conference Shaw slipped out of the room and flew back to Dallas.

Almost everyone who saw the journal believed that it was a fraud. John Stockwell, the CIA-agent-turned-author, pronounced the work “a crude fabrication,” pointing out that though the journal was supposedly written between 1957 and 1971, it appeared to be written in the same felt-tip pen. Felt-tip pens weren’t used until the early sixties. A more obvious flaw was a mention on the next to last page of Watergate—apparently Watergate was to be Roscoe’s last assignment, which he refused. The problem with this—other than believing that a man who had killed the president and numerous others would dig in his heels at the idea of taking part in a two-bit burglary—is that the break-in at the Watergate apartment complex didn’t occur until ten months after Roscoe White died. The scandal that we now know as Watergate wasn’t called that until weeks after the break-in. When I mentioned this to Joe West after the press conference, he became indignant and gave me a lecture about how the term “watergate” is more than two thousand years old and appears in the third chapter of the Book of Nehemiah.

The new journal fractured the tentative harmony within the White family. “That’s not my daddy’s handwriting,” Ricky protested. “And that’s not the way he wrote.” There was a whiny, cringing, self-pitying tone to the prose, strikingly unlike Rock White’s lean, spare style. The language was turgid, overburdened with regrets for what a rotten husband he had been, and gushing with appreciation for Geneva—“God thank you for Geneva. I’ve got me one hell of a woman. Thank you thank you God.”

Ricky and Tricia believe that Geneva created the journal. I think that’s a sound supposition. Given her nearly hopeless financial situation and the constant admonitions of others, imploring her to come up with some new piece of evidence—something else—the creation could be viewed more as an act of desperation than a hoax.

Maybe it shouldn’t, but this latest journal tends to discredit all the other evidence. If the entire Roscoe White story is a hoax—and that is a distinct possibility—it is a hoax created by someone with an impressive knowledge of assassination details, a good grasp of intelligence operations, and some insight into organized crime. Maybe Roscoe White himself perpetrated the deceit. Or maybe it was the work of his mysterious friend Bill X, with some help from Geneva.

Considering all the bizarre happenings since 1963, the scenario appears rather tame. If you want to fault the Roscoe White story, fault it first for its lack of imagination.