God bless Ted Cruz, and pass the popcorn. The sheer volume and variety of complaints against our freshman senator over the past month is a clue that he’s hit a nerve. The question is, is it a nerve worth hitting?

At issue, of course, is the Affordable Care Act, Obamacare for short. The law is scheduled to take effect October 1, except for the parts of it that have already been delayed, by the clemency of President Barack Obama. Cruz, along with Utah’s Mike Lee and a handful of Republicans who have since rallied round, is hoping to persuade his colleagues in Congress to refuse to appropriate any money that would help fund the law. His weapons are an online petition and a willingness to barnstorm around the country talking about it, which is what he’s been doing during the Senate’s summer recess.

Everyone, including Cruz, knows that he’s not likely to succeed. Democrats control the Senate, plus a lot of Republicans don’t want to have this fight (plus Obama, the president who signed the law in the first place, is still president—even if some Republicans still aren’t resigned to that fact). And yet almost everyone, other than Cruz, is acting surprisingly irritated and defensive all of a sudden. Reading some news accounts, you would get the sense that this is just another one of those stunts that Americans have come to expect from Cruz, like that time (also this month) that it turned out he has dual citizenship in Canada and didn’t even know it. From left-leaning pundits, we see bravado with a side of aggrievement: Cruz’s campaign against Obamacare is doomed to fail. But he might trigger a government shutdown, which would be bad for all Americans. In the meantime, if anything, he’s helping to show how dangerously appealing Obamacare is; he’s said himself that it’s critical to stop Obamacare before implementation, because once Americans start having health insurance they’ll get used to it. Even on the right, many politicians and commentators seem annoyed: Obviously it’s too late to defund Obamacare now, so Cruz is just trying to strong-arm other Republicans into signing up for a losing fight. And if there is a government shutdown, the whole party, even those above-the-fray Republicans that Cruz has allegedly dubbed the “surrender caucus,” will share the blame for it.

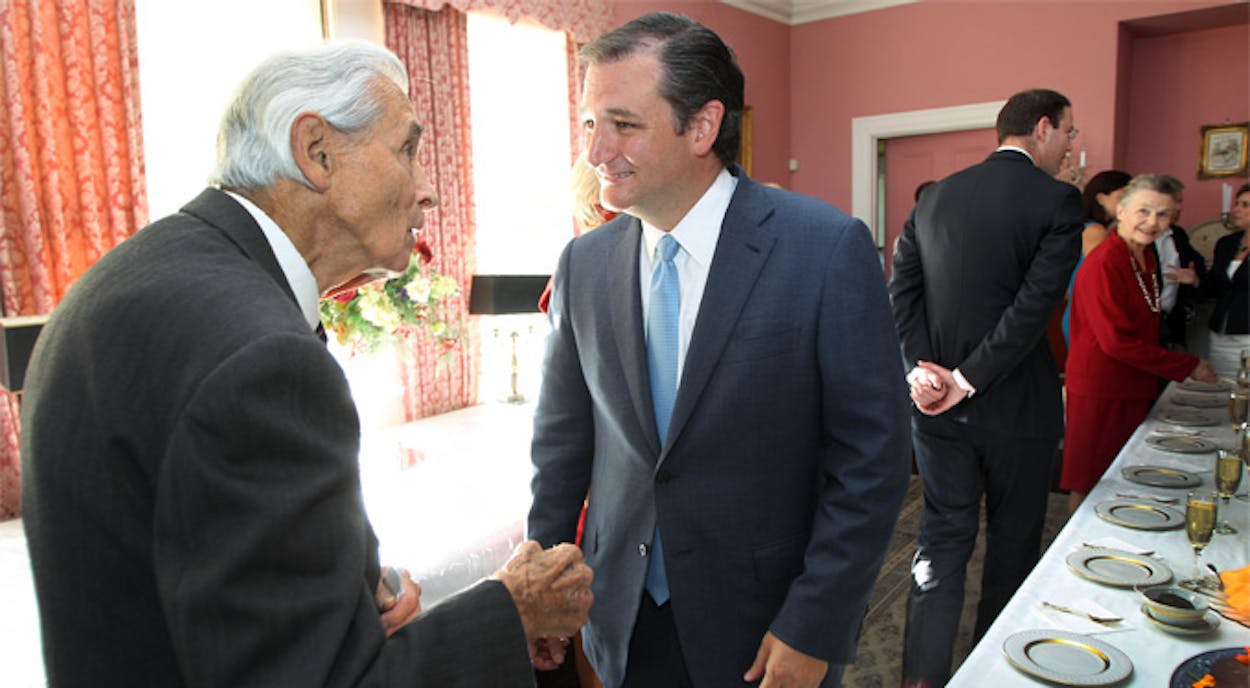

It’s a lot of backlash, given that most of the critics are united behind the premise that the defunding effort is bound to fail—a premise that’s probably correct. It’s a lot of sniping, considering that in opposing Obamacare, Cruz is hardly taking up a tinfoil-hat-type cause; lots of Americans are disgruntled about this law. And it’s a lot of scolding to throw at a guy who, Canadian though he may be, is also an American and therefore entitled to exercise his First Amendment rights just like the rest of us. Last week I hitched a ride with Cruz from a ribbon-cutting ceremony at Austin’s new VA clinic to Waco, where he was the keynote speaker at a benefit for West, Texas. The campaign to defund Obamacare was the first thing we discussed.

The effort had, he said, been getting a “tremendous” response, both in person and via the online petition. “The reason is, it’s becoming clearer and clearer that Obamacare’s not working, and that it is the number-one job killer in the country,” Cruz told me. “It’s causing more and more people to be laid off, and not to be hired in the first place, and it’s causing people to have their hours forcibly reduced.”

A few days ago he had, he said, met a woman at a Hill Country roundtable who owned several fast-food restaurants. She had said that she was cutting all of her employees’ hours so that she wouldn’t have to provide them with health insurance; it was breaking her heart to do that, she said, because she knew they couldn’t care for their families on 29 hours a week, but at the same time, Cruz added, the workers could hardly care for their families if the restaurants went out of business. Another business owner, at that same roundtable, had said he wanted to do more manufacturing in Central Texas, but the rule that employers with more than fifty employees should provide insurance made it too expensive, and so he had been forced to send those jobs, between 150 and 200 of them, overseas.

“I think so many people are being hurt by Obamacare,” Cruz said. “ And, in particular, the people who are being hurt are the most vulnerable. They’re young people, Hispanics, African-Americans, single moms.” Those groups, he meant, are particularly vulnerable to harm because the Affordable Care Act was indirectly reducing their access to jobs.

Other people, Cruz continued, are getting hurt because they’re actually losing their health insurance: “Just this week we have seen that a number of employers are dropping spousal coverage. UPS sent letters to 18,000 employees that said your husbands and wives will no longer be covered. 18,000—their spouses have just lost their coverage. Now, when Obamacare was being proposed, the president told the American people that if you like your health care, you can keep it, and that is proving every day less and less true.” (The figure was actually 15,000, but as Cruz noted, UPS isn’t the only employer who has made such an announcement recently, pointing to the Affordable Care Act as at least one factor.)

Earlier that day, Cruz had been at a roundtable for tech executives in Austin, so I asked if the executives at bigger companies, similarly, described the Affordable Care Act as a constraint on their growth. One CEO had, Cruz said, but for the high-tech employers, all of whom were already providing some form of insurance, the stakes were slightly different.

“I will share a conversation that one of the executives from one of the high-tech companies had,” said Cruz, “He said more and more large companies are just waiting for cover to dump their health insurance altogether, because the expenses are getting so high. That was said by an executive at one of the large tech companies—that he is hearing from his peers at other companies that as long as there’s any credible place to push their employees, big companies are getting ready to dump their health insurance coverage. I mean, this thing isn’t working.”

If that’s true, I observed, then presumably the people who lose coverage through their employer will be able to get coverage through the exchanges, so they’re not actually going to lose coverage altogether.

“Yes,” agreed Cruz, “But it’s interesting. Another one, a different exec at one of the high-tech companies, said his employees had been coming and saying, ‘We really like our health insurance, what we have that our company provides, can you promise that we’ll be able to keep it?’ And he said he’s having to tell them, ‘No, I can’t promise you that; the costs are going up so high.’ I mean, his perspective is, as Obamacare forces more and more people to be thrown off their health insurance coverage, or lose coverage, that it’s all headed towards single payer, to a government-provided, single-payer, socialized health care system.”

I asked for clarification.

“I understood him to mean,” Cruz said, “that as private insurance became less and less affordable and accessible, the only option that would be left is for the government to step in and provide government-provided socialized medicine–that that’s where this is headed.”

I told Cruz that, from my perspective, he’s lucky. As a member of the Senate’s minority party, he can oppose Obamacare all day long, without being expected to offer an alternative. Still, though, what would his alternative be?

“I think there’s a real need for health-care reform,” said Cruz. “The first priority is to defund and repeal every word of Obamacare, because it’s not working, because it’s killing jobs, because it’s driving up health insurance premiums, because it’s hurting the American people. Once that’s done I think we need serious health care reform, and I think that reform should follow a couple of key principles.”

Cruz then launched into an epic soliloquy, with basically no interruptions, dysfluencies, or rhetorical cul-de-sacs.

“Number one: it should expand competition and use of the marketplace. Number two: it should empower consumers to exercise choice to meet their health-care needs. And number three: it should disempower government bureaucrats to second-guess and get in between doctors and their patients in making health-care decisions. Those are all general principles. Now let me give three specific policy proposals that are manifestations of those principles.”

“Number one: I think we should allow people to purchase health insurance across state lines. Right now it’s illegal to do so. What that would do is create a true, fifty-state, national marketplace for health insurance. Right now, the biggest barrier to health insurance for many of the uninsured is the cost—that health insurance is very, very expensive. And a significant reason health insurance is so expensive is because of all the bells and whistles that are mandated by government. If we had a true, fifty-state marketplace, what we would see is the widespread availability of low-cost, catastrophic health insurance policies, which would expand coverage dramatically, because the costs would fall and they would be far more accessible to people who can’t afford it right now. That’s number one.”

“Number two: we need to significantly expand the use of health savings accounts, so that people can save, in a tax-advantaged way, for prevention, for routine health maintenance, for challenges that are short of catastrophic, but nonetheless health-care needs that people have.”

“And number three: we need to work to delink health insurance from employment. As you know, it is an historical accident that health insurance is typically tied to employment. It actually arose during World War II and shortly thereafter, when wage and price controls were in effect, and employers were unable to recruit employees using higher salaries, and so they began using health insurance and other perks as ways to recruit new employees.”

“Right now,” Cruz continued, “If you or I lose our jobs, we don’t lose our car insurance. We don’t lose our life insurance. We don’t lose our house insurance. There’s no reason on earth we should lose our health insurance. And of all of them, I think health insurance is the worst one to lose. And so we need to change federal law to make health insurance policies portable and personal. So just like with your car insurance, if you leave your current job and go on to another one, you take your car insurance with you. And that change goes a long long way to solving the problem of pre-existing conditions, because pre-existing conditions become a major barrier to health care when someone loses their job and then have to get a new policy, rather than if they are able to maintain their policy throughout.”

“Now, the difference between those three specific proposals and the approach of Obamacare,” added Cruz, “is Obamacare relies on central planning, on the federal government interposing its judgment into the middle of decisions between doctors and patients. And I think the right approach is exactly the opposite: we should empower patients, we should empower individuals, to take control of their own health-care decisions.”

This plan has a few problems, or, to put it another way, doesn’t solve some of the key issues with the status quo that prompted Obama and the Democrats to pursue health-care reform in the first place. First, some people are uninsured because private insurance companies are reluctant, if not outright unwilling, to insure them. That makes sense from a market perspective, but it’s a cruel situation for people in question and their loved ones, not to mention burdensome for the hospitals that have to absorb the cost of uninsured care, and so on. (Cruz had implicitly addressed this earlier, with his comment that the problem of pre-existing conditions often arises because health insurance is often provided by employers—but I didn’t explicitly ask about it later in the conversation.)

Another group of troublemakers: young people. Low-cost castastrophic insurance is already available, and millions of people who are uninsured could presumably afford it; they just don’t think it’s worth it. That’s why the Affordable Care Act includes an individual mandate to buy health insurance, or else face a penalty. “Look, there are people today who make rational decisions not to purchase health insurance,” said Cruz when I asked about that aspect of things. “Much of that is driven by the price.” In a genuinely competitive market, health care costs would come down, just as the price of LASIK eye surgery has dropped considerably since the technique was first introduced; because people generally pay for LASIK out of pocket, that is, doctors have an incentive to compete for their business by offering lower prices. Extending that thinking, he continued: if the market for health care services was a genuine market, which it currently isn’t, there would be competitive pressure on insurers to lower the cost of their policies, so that young adults would sign up. Hard saying not knowing, of course.

Still, whether or not you prefer Cruz’s approach to Obama’s, I would say he’s hardly out of line in offering this line of critique. The Affordable Care Act has always been controversial, and the road to implementation has, obviously, been rocky. The bill was sold with the promise that people would be able to keep their extant health insurance if they were happy with it, which is proving not to be true for some of them. (In his 2010 State of the Union address, in fact, Obama referred to that as a “right”, which was probably overstating the case.) Projections about the number of people who still won’t have insurance after the ACA is implemented have crept up: the independent analysts at the Congressional Budget Office expect there to be 31 million people left uninsured in the country, compared to 30 million in their previous projection. Business owners have warned that the law is constraining their ability to operate and willingness to expand, which isn’t good for workers. Plenty of people take that complaint seriously—including, significantly, the Obama administration itself. “We are listening,” wrote White House senior advisor Valerie Jarrett in June, announcing that the administration would give businesses “more time to comply” with the law’s provision that employers with more than fifty employees have to provide health insurance.

Cruz is, in other words, making some valid points about Obamacare. Some of his objections are the same ones that Congressional Republicans had before the bill was passed, and that’s a fight that they lost—so even though Cruz hadn’t been elected to the Senate at that point, it is a little odd to try to retroactively filibuster the legislation. His primary critiques, though, are about what has happened since the law was signed and since the Supreme Court upheld it, and it would be disingenuous for Democrats to say that the road to implementation has been no more difficult than expected. At the same time, Democrats can still argue that the Affordable Care Act is a worthwhile reform. There are almost sixty million people in the country without any health insurance at all, and the Affordable Care Act is the only reform available in the next few months. Democrats should, in fact, argue that. They won’t necessarily be right, but it would be more respectable than attacking Cruz for pointing out some of the consequences of a massive, expensive, and far-reaching law.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Health

- Ted Cruz