Here’s a secret, one which I’d appreciate you don’t tell our engagement editor I told you: you don’t really have to pay any attention to the Democratic primary until January or so. In fact it’s probably better for your sanity that you don’t. The primary could look like the Republican one in 2012, when a succession of minor candidates rose and fell in the polls (Newt Gingrich! Herman Cain! Rick Perry!) or it could look like the Republican one in 2016, when one candidate pulled into the lead and stayed there, or anything in between, and however it turns out won’t be affected by you checking out and checking in again a little before people actually start to cast votes. No civilized society should have elections that last this long, and there’s a risk that the 25-candidate field simply exhausts people by their presence in the same way the president exhausts people.

But the candidates themselves can’t check out, poor devils. (Neither can reporters.) For the foreseeable future they’ll be clambering over each other like Navy midshipmen up a greased pole for any kind of incremental advantage, because in this field pulling two percent in the polls instead of one percent could mean fifth instead of fifteenth place. This week, the greased pole is in Miami, where twenty candidates are debating over the course of two nights. Debate is a stretch, perhaps—at last night’s installment, each candidate talked for between five to eleven minutes each.

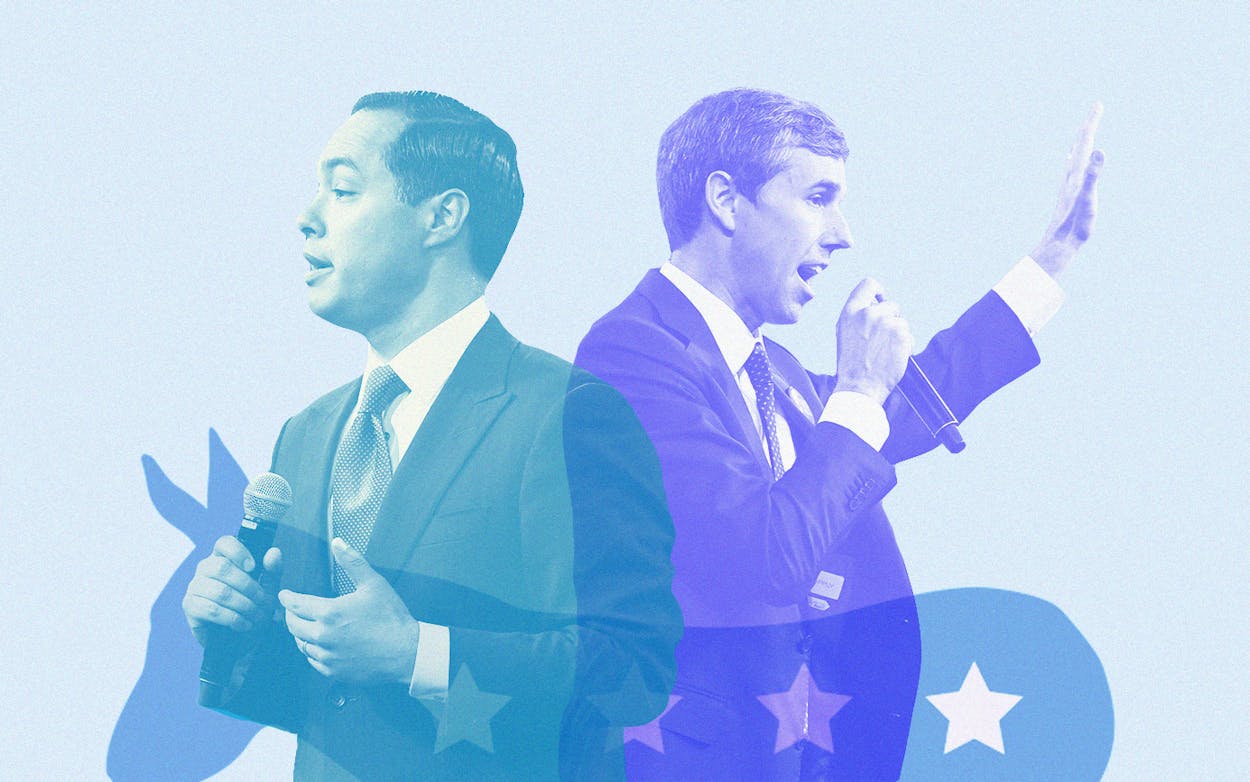

The two Texans in the race have consistently struggled to get traction. Beto O’Rourke succeeded in bringing very little of the glamour of the 2018 Senate race with him when he leveled up. His first day was his best day, even though it came soon after a glossy Vanity Fair profile that rubbed a lot of people the wrong way. Since then he’s “re-launched” his campaign—again, more than seven months out from any vote—and though he’s stuck around with about five percent in polls, he needs something to change.

Julián Castro, meanwhile, hasn’t gotten out of the starting blocks, which is a bit strange. He’s the only Hispanic candidate in the field, the first one to come out with an immigration policy package, and is a former cabinet secretary and mayor of a large city. That’s no great shakes as far as the level of experience we traditionally expect from presidential candidates, but it’s better than most of the others. (O’Rourke, for example, has never held an executive position, and Pete Buttigieg is the mayor of a small city in Indiana.) Resentment about the way Castro has been treated in the media has been building in the Castro campaign over the months, perhaps justifiably.

Something strange happened at the debate last night. The most popular candidate onstage was Elizabeth Warren, one of just three contenders to have double-digit support in polls. But the other candidates didn’t attack Warren, by and large. Instead, they dragged O’Rourke, who didn’t take it that well. And the candidate landing the hardest punches was Castro, who extended his suddenly personal attacks after the debate and this morning. It had the feel, at times, of an episode of Survivor—the little guys teaming up to clear their ranks before the real fight begins.

First, on his own terms, O’Rourke seemed strangely enervated throughout the night. One of the several problems he’s had since launching his campaign is translating the style that he used to great effect on the road in Texas to the national stage, where everything is mediated and more impersonal by necessity. He struggled with that last night, too, but he also made some odd choices. When asked an opening question about marginal tax rates, he declined to answer the question specifically and instead switched to Spanish. (Later, on MSNBC, he said he was not in favor of a 70 percent marginal income tax rate on the highest earners.)

When Warren was asked a question about health care, she responded in the fiery and passionate manner Democratic primary voters are into right now, ending with a declaration that health care was “a basic human right, and I will fight for basic human rights.” Immediately after, O’Rourke was asked if he had flip-flopped on the issue of universal health care. He started meandering in an uncharacteristic way: “My goal is to ensure that every American is well enough to live to their full potential, because they have health care,” he said, before telling a story about a man he had met in Laredo.

Bill de Blasio jumped on him for that answer, but when the subject turned to immigration it was Castro’s turn to stick the knife in. In probably the most noteworthy exchange of the night, Castro objected to O’Rourke’s immigration plan, arguing that it didn’t address what he said was the core issue underlying practices most Democrats consider to be abusive—the provision of U.S. code that makes it a misdemeanor to enter the country without papers, USC 1325, or illegal entry. Unauthorized entry should be treated as a civil violation, he has repeatedly said, and doing so would prevent the government from locking up migrants and separating them from their children.

As O’Rourke was speaking about the importance of treating refugees well, Castro interrupted him. The tool that the government was using “to incarcerate the parents and seperate the children,” he said, was illegal entry. Castro had called to repeal it, and other candidates had followed him. O’Rourke had said he thought repeal was a bad idea. Why?

O’Rourke responded that he had supported legislation in Congress to ensure that the government honored those “seeking safe refuge and asylum,” adding that Castro was “talking about one small part of” the issue. But the issue the two were discussing was about all sorts of undocumented poeple, not just refugees, and Section 1325 is a big deal, not a small one. Castro reminded O’Rourke that he had recently said he opposed repealing Section 1325 because of concerns about prosecuting human trafficking and drug smuggling, but those things would still be illegal even if illegal entry didn’t exist as a crime. Castro landed his final blow: O’Rourke would’ve known that “if you did your homework on this issue.”

The moderators cut the exchange off, as they always do when something interesting happens. In his ability to communicate his grasp of the issues, Castro had the upper hand. As to the politics, it’s hard to say—it will sound like “open borders” to a lot of people, though Trump will accuse Democrats of that no matter what they do. But in that moment, the exchange wasn’t really about policy or politics, but about Castro, held back in the polls, making good use of a chance to trip up a second-tier candidate who already suffers from the perception of deflecting on issues and phoning it in.

He doubled and tripled down after the debate. It was important, Castro told MSNBC’s Chris Matthews, that the eventual nominee be able to “speak in an informed way about the policies of this administration.” About O’Rourke, he said again, “I don’t think he’s done his homework,” he said. “I think he was misinformed.” And then, the killshot: “I think it’s ironic that a senator from Massachusetts and a senator from New Jersey and a congressman from Ohio have a better understanding of immigration law than Congressman O’Rourke.”

How will this play? Who knows. Castro’s performance was otherwise strong, and his supporters noted a 2,400 percent increase in Google searches for his name after the debate. Meanwhile, furious Beto fans on social media proclaimed they would never, ever vote for Castro. They noted he had campaigned for O’Rourke for Senate, and called Castro a hypocrite, which is of course a nonsense complaint.

But it’s possible none of this posturing between lower-tier candidates really turns out to matter. At the end of the night, the person with the most solid performance on stage, generally unchallenged by rivals, might have been the third (honorary) Texan on stage—University of Houston graduate Elizabeth Warren.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Julian Castro

- Beto O'Rourke