The sun had not yet risen when Ken Paxton stationed himself in downtown Dallas. This was the July morning after a peaceful Black Lives Matter protest had ended with a sniper’s killing five police officers and wounding nine others, and the city center had become one massive crime scene. Paxton stood inside the yellow police tape, but he wasn’t there to investigate. The attorney general is often referred to as Texas’s top law enforcement official, but that description is incorrect. While divisions within the agency do hunt down sexual predators and human traffickers and, when requested, assist local district attorneys in prosecuting criminal cases, the attorney general is actually the state’s top lawyer. Paxton himself has no law enforcement background. As an attorney, he’s specialized in estate planning as well as probate and corporate transactions. In fact, his most extensive experience with the criminal justice system has come on the wrong end of it. In July 2015, seven months after taking office, he’d been indicted for securities fraud, including two first-degree felonies. So that morning in Dallas, Paxton had no official role—the city’s police and prosecutors were handling the case, and if they needed help, they could call upon the Texas Department of Public Safety, the Dallas County sheriff’s office, and even the FBI. But Paxton had driven downtown for a specific purpose. He was there for the exposure.

With the crime scene as a backdrop, Paxton gave one television interview after another. What the reporters and anchors wanted in the confusing whirlwind of that early morning was information, but each interview revealed that Paxton was hopelessly out of the loop. On CBS This Morning at 7:09, Paxton had to answer questions with phrases like “I don’t know,” “I’m not sure of that,” and “I have not gotten an update.” Even by late morning, Paxton had to tell one reporter, “Actually, I don’t know a lot of details yet.” Perhaps no exchange was more revealing than the one with ABC’s Good Morning America host George Stephanopoulos.

For that interview, Paxton stood in front of a police car, its flashing lights bouncing off the pavement in the dark morning. At age 53, Paxton has a receding hairline, and his appearance is soft, with the complexion of someone who doesn’t spend much time outdoors. A sports injury in college left him with a sleepy right eyelid and a crooked smile that can look like a smirk.

“What more can you tell us about those injured officers now in the hospital?” Stephanopoulos asked.

“Let me just say, this is a sad day for Texas,” Paxton replied. “It’s a resilient state. But we’re praying for the families as well. We’re not going to forget these fallen heroes, and we want the families to know that we support them. I don’t have a lot of details yet on the condition of some of the people who were injured, but I think we’ll have that relatively soon.”

Stephanopoulos pressed for details. “Do we know if it was two or if there were more [shooters]?” Paxton had a vague expression on his face. “There are still many, many policemen down here investigating that. I don’t think they’ve made a final determination.” Were all the suspects in custody, Stephanopoulos asked. “I’m not sure we totally know that,” the attorney general said. Paxton, with a bang of hair falling down toward his eyes, resorted to stating the obvious. “This is still a major crime scene,” Paxton said. “It’s the largest one I’ve ever seen. I used to work a couple of blocks from here. It’s very surreal, and it’s like nothing I’ve seen in downtown Dallas in the twenty-five years or so that I’ve been here.”

Texas’s top two elected officials were also in Dallas that day. Governor Greg Abbott had cancelled a family vacation and returned to Texas and offered up the resources of the Department of Public Safety to the city. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick consoled families of the fallen and wounded officers at Parkland and Baylor hospitals (later in the day, he made a controversial statement blaming protesters, in part, for inciting the shooting). As Abbott dealt with a serious injury—unbeknownst to the public, he had suffered severe burns to his legs and feet while on vacation—and Patrick comforted victims that morning, Paxton used the Dallas tragedy to appear as often as possible on television.

As the day wore on, there were more interviews: Fox & Friends, CNN New Day, Morning Joe, Glenn Beck TV. Paxton conducted eighteen television interviews before taking a break at 5 p.m. to stand behind Abbott at a news conference with Mayor Mike Rawlings, and then did four more appearances that evening. And he was back at it four days later. On the Tuesday after the shootings, Paxton sat for four morning interviews, then paused to attend a memorial service for the officers led by President Barack Obama. Forty minutes after the service ended, Paxton was back on CNN with host Jake Tapper.

Paxton’s affinity for the spotlight was a recent development. In fact, two months before the shooting, he’d used state funds to hire a public relations firm to help burnish his image. But prior to that, Paxton had been an elusive figure for the media, especially the state’s major newspapers. After securing the Republican nomination in 2014, he’d barely bothered to campaign in the general election, shunning media appearances and candidate forums. The Houston Chronicle described him as running a “shadow campaign.” Even recently, while he frequently appears on television, he has offered few interviews to the mainstream print media. (Paxton refused numerous interview requests for this story over two months, though he answered a few questions submitted by email.)

But by watching hours of video of his speeches and interviews, by speaking with agency insiders, and by culling hundreds of pages of documents obtained through open-records requests, we saw a portrait emerge of Paxton’s first two years in office.

He appears to be a politician more interested in having the title of attorney general than being attorney general. He has used his office as a cudgel in the culture wars for the Christian right. He’s continued to live in McKinney, about thirty miles north of Dallas, rather than move to Austin for the daily duties of running his office. As a result of his absence from the office, he’s grown jealous of aides, who have received the positive media attention that has eluded him, a feeling that apparently intensified after he was indicted. In March, he got rid of his top staffers, replacing them with religious-right activists, and hired two public relations firms that specialize in crisis management. Suddenly, the once-reclusive Paxton was often popping up on television and at press conferences, discussing lawsuits and events—like the Dallas sniper case—with which he had little direct involvement. With his own criminal trial now approaching, publicity, it seems, has become Paxton’s affirmation.

If the attorney general’s office were a private law firm, it would be among the largest in Texas, with more than seven hundred lawyers, 30,000 cases in progress, and a two-year budget of $1.15 billion. Its lawsuits range from enforcing mundane actions by state regulatory agencies to protecting the state’s authority to carry out death sentences. The agency is also charged with collecting delinquent child support payments; it took in $3.8 billion last year that was owed to about 1.7 million children. And the state’s new open carry law gives the office power to sue local governments that block the carrying of firearms on government property. The AG’s office also offers legal opinions, represents state entities in court, determines which government documents can be released to the public, prosecutes political corruption and voter fraud, and protects Texas consumers from predatory businesses. In short, the office has broad authority. It could be argued that the attorney general has a greater influence on the daily lives of Texans than

the governor.

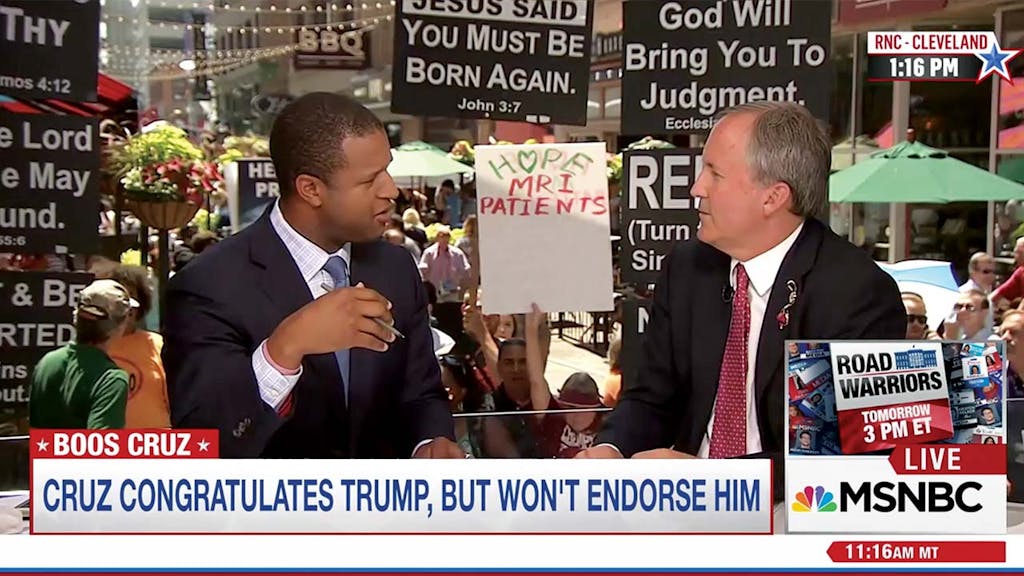

In political philosophy, Paxton is similar to his two most recent predecessors, Abbott and current U.S. senator John Cornyn. Paxton has continued to fight the Obama administration on numerous fronts in court, picking up where Abbott left off. Paxton’s lawyers won court rulings halting an Obama immigration order and lost in the defense of the state’s anti-abortion law and the ban on same-sex marriage. Paxton noted, in a speech to Texas delegates at the Republican National Convention in July, that his office had filed a dozen suits against the federal government in his first eighteen months in office. “So we’re on a really good pace,” he said.

But while their ideologies may be similar, Paxton’s predecessors had far more distinguished résumés. Before they became attorneys general, Cornyn and Abbott had been accomplished litigators, and both had served terms on the Texas Supreme Court. And once they were elected attorneys general, both had reputations in the office for making the final edits on the state’s largest lawsuits, and Abbott confidently allowed his chief appellate lawyer, solicitor general Ted Cruz, to shine in public, putting Cruz on the path to winning election to the U.S. Senate.

Paxton, meanwhile, wasn’t exactly a towering figure during almost a dozen years in the Legislature, as a representative and later a senator. He passed few bills of statewide importance. Perhaps the most notable piece of legislation that he passed was one requiring “Welcome to Texas” highway signs to include the phrase “Proud to Be the Home of President George W. Bush.” (Paxton later amended the statute to remove the phrase after Bush left office.) Before the 2011 session, he ran against incumbent Joe Straus to become Speaker of the House, but he surrendered before the vote was taken because he’d failed to rally enough support in the Republican Caucus.

However, the bills Paxton didn’t get passed were probably more important to his political ascension. He carried a bill to prevent school districts from obtaining sex-education materials from organizations like Planned Parenthood, and he co-authored a state constitutional amendment to protect from lawsuits individuals and businesses that refused to provide services because of religious objections. And he rallied support for legislation to require women to get a sonogram before an abortion. These proposals made Paxton a favorite of religious conservatives, and they aligned with his own fundamentalism.

Paxton has been married to his wife, Angela, for thirty years, and they have four children. They met as undergraduates at Baylor University, and she refers to June 1 as “I Love You Day,” the anniversary of the first time Paxton spoke those words to her. They were among the founders of the nondenominational evangelical Stonebriar Community Church in Frisco, just west of McKinney, where Angela would mentor young women, teaching them how to dress modestly but with style. He’s served on the board of the Prestonwood Pregnancy and Family Care Center, an agency dedicated to steering women away from abortion. The Paxtons later moved their worship to Prestonwood Baptist Church, a mega-congregation on two campuses in the northern Dallas suburbs, which is built on the “inerrant truth of the Bible.” With the exception of the fraud indictments against him, Paxton is a pillar of his community, a fundamentalist who wears his Christianity on his sleeve.

Former law partner George Crumley said Paxton is one of the last people he would have expected to go into politics. “I can’t say that he’s shy, but he’s certainly not the guy who is the life of the party,” Crumley said. Paxton is “solid and trustworthy” but, if anything, spreads himself too thin. “If Ken had a fault in all of this it was that he had too much going on, too much on his plate. You need to make sure you don’t let things slide. Ken is probably a victim of his own success and popularity.”

When Abbott decided in 2013 to run for governor, an opportunity opened for Paxton. His main Republican primary opponent in the spring of 2014 was state representative Dan Branch, a respected Dallas lawyer with close ties to Speaker Straus. Both Branch and Straus were seen as insufficiently conservative by many Republican primary voters, and Paxton had pastors, tea party groups, and the rigidly conservative Cruz on his side. “My strategy was very simple . . . get the church out to vote,” Paxton told an audience at the First Baptist Church in Denison this past August. He was referring to his first run for the House, in 2002, but it’s also exactly how Paxton defeated Branch in a runoff. More than two thirds of Republican voters in the primary and runoff attended church at least once a week, if not more, according to a survey by the Republican consulting firm Baselice & Associates. With Democrats perpetually overmatched, winning the Republican nomination was tantamount to capturing the office in November.

A dark specter lurked in the background during that election, though. Paxton conceded that he had failed to list all his business interests on a financial disclosure document. Even more damning, he admitted to the Texas State Securities Board that he hadn’t registered as a securities dealer promoting investments. He received a reprimand and a $1,000 fine. Partisans, reporters, and political junkies knew of Paxton’s transgressions before the election, but the allegations didn’t sink in with the general public until after he was in office.

In July 2015 a Collin County grand jury indicted Paxton on two first-degree felony counts of securities fraud and a third-degree felony for failing to register as a securities dealer. The indictments charged Paxton with improperly encouraging investors in 2011 to invest more than $600,000 in a technology firm called Servergy Inc. Paxton allegedly didn’t disclose to his clients that he was getting paid for steering investors to Servergy. The company also allegedly lied to potential investors about its funding sources; for example, its CEO told investors that Amazon was ordering Servergy’s products, when, in fact, a single Amazon employee had merely wanted to test one product, according to Securities and Exchange Commission documents. (It’s not clear if Paxton knew about these alleged misrepresentations.) Paxton’s appeals and legal filings have delayed the case for more than a year, but the state’s highest criminal court recently threw out his latest challenge, clearing the way for a trial in the coming months. “There is an indescribable peace in our family when, in the depths of our being, we know that I am innocent,” Paxton wrote in response to questions from Texas Monthly.

Paxton is the first sitting Texas attorney general to be indicted in more than thirty years, and his fate may hinge on whether he was merely being sloppy or intentionally misleading clients. Two years ago, before his indictment, Paxton claimed it was the former, attributing his problems to legal ignorance. “Listen, there’s no lawyer who’s an expert on every area of the law,” Paxton told KERA, the Dallas NPR affiliate, in 2014. “Securities laws are very complicated.”

When Paxton took office in January 2015, there was concern among Austin’s cadre of elected officials and lobbyists about whether he was prepared to handle one of the most important jobs in state government. But they were reassured when Paxton started surrounding himself with respected political and governmental veterans. The office, it seemed, would not be bumbling.

Paxton hired Chip Roy as his first assistant, Bernard McNamee as his chief of staff, and Scott Keller as his solicitor general. All three had been part of Cruz’s Senate office staff; Roy had been Cruz’s chief of staff and before that had worked for Cornyn and former governor Rick Perry. For communications director, Paxton hired Allison Castle, who had done the same job for Perry. It was an undeniably solid team with years of experience in state and federal government, the kind of staff Paxton would need, especially after deciding to continue to live in North Texas and visit the agency just a few days a week.

From his own campaign staff, Paxton hired Michelle Smith to oversee outreach to voters. Smith had previously been a member of the Rockwall City Council and the state director for Concerned Women for America. Her CWA biography states she has “worked hard to elect Christian conservative leaders.” Though the rest of the team was based in the attorney general’s headquarters, Smith was assigned to a Dallas office so she’d be readily available to Paxton.

While legal, Paxton’s decision to live in McKinney instead of Austin has been costly to taxpayers. As with other statewide officials, Paxton receives personal security from DPS, but when the officers are outside Austin, they incur travel expenses. Through May 2016, the extra cost of providing security for Paxton at his Collin County home exceeded $57,000, according to records from DPS.

In written comments, Paxton defended his decision to stay at home in McKinney, arguing that with modern technology there was no reason for him to work most days in Austin. “I spend every day tirelessly defending, promoting, and serving our great state, whether in Austin, traveling around Texas, or close to home with my family.”

The first major case facing Paxton after he took office was defending the state’s ban on same-sex marriage before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit while a similar case was pending before the Supreme Court. When the nation’s high court ruled that same-sex marriage was a constitutional right, Paxton’s response created confusion. In an official opinion, he outlined how a county clerk who had religious objections to same-sex marriage could pass the duty off to another clerk or simply refuse to issue any marriage licenses. In a statement, Paxton called the ruling “lawless” and urged clerks to stand against it by refusing to issue licenses, saying private attorneys would represent them for free. This was a remarkable moment. Here was Texas’s top lawyer advising his constituents to disregard a ruling from the Supreme Court. One clerk, in Hood County, followed Paxton’s advice, and the county ended up paying almost $44,000 in legal fees when a lawsuit forced it to back down. Though Paxton’s defiant stance on same-sex marriage was widely criticized by Democrats and progressives, his political base of social conservatives loved it.

And Paxton would draw on that goodwill later that summer when his felony indictments were handed down. After he was indicted, Paxton grew even more media-shy. His public speaking was limited to friendly audiences at churches and tea party events, and he withdrew from his office too, spending more and more time at his home in McKinney. Often he was unavailable for days, with his aides unable to find him for needed responses to questions. All elected officeholders travel the state to speak to civic groups and promote their policies, but the difference for Paxton was that he had disengaged, according to AG office sources. An unrelenting stream of news stories portrayed Paxton not as attorney general, defender of the unborn, individual religious liberty, and Second Amendment rights, but rather Ken Paxton, accused felon.

Paxton became concerned that—with his absence from agency headquarters—his aides were getting more positive attention than he was. Everything done by the attorney general’s office occurs in Paxton’s name, but after his indictments, that simply was not enough. While speaking at the Pflugerville First Baptist Church in September 2015, Paxton praised first assistant Roy as one of the “visionaries on this religious liberties issue,” but Paxton prefaced it by self-consciously saying, “I get credit, sometimes not credit, for what happens in my office.” The speculation circulating Austin was that with Paxton not around, Roy was the actual attorney general of Texas. Meanwhile, a frustrated McNamee resigned as chief of staff in November to return to private practice in Virginia. Then came two reports that prompted a crisis within the office. In February of this year, the Texas Tribune posted an interview with Roy and solicitor general Keller on the upcoming U.S. Supreme Court arguments challenging President Obama’s executive order shielding some undocumented immigrants from deportation. When reporter Julián Aguilar went off topic to ask how Paxton’s legal troubles were affecting the agency, Roy responded in a way that implied that the attorney general was often absent from the office: “We’re in constant communication with the attorney general, and we’re focused on doing our job every day to defend the state of Texas. . . . The first assistant attorney general, the solicitor general, our head of civil litigation, all of us are charged to manage the daily affairs of this agency, and that’s what we’re doing.”

On March 1, the New York Times profiled Keller and Stephanie Toti, a lawyer for the Center for Reproductive Rights, as they prepared to face off before the U.S. Supreme Court over Texas’s new restrictions on abortion clinics. The fight to preserve the anti-abortion law was one of Paxton’s signature issues, but his name didn’t even appear in the Times piece. Castle, the communications director, and her staff had contacted about fifty national news organizations but could not get Paxton any major interviews. Tension grew between his political aides and the agency staff. Agency insiders said that while sitting in the Supreme Court cafeteria, Smith, Paxton’s political aide, pulled up a copy of the Times article on Keller, turned to a communications deputy, and complained that she was “sick and tired” of seeing other people’s names in the papers. Smith denies the exchange occurred. (The Supreme Court would later overturn the law’s most restrictive measures, saying it placed an undue burden on a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion.)

Paxton had traveled to Washington for the oral arguments. He bought his own tickets on Southwest Airlines on a promotional “Wanna Get Away” fare, for a round-trip total of $450. And in what appears to have been a fit of petty pique, a handwritten note was included on a voucher submitted to the state that read, “Purchasing own airfare resulted in conservation of state funds.” Attached to it was a copy of Roy’s voucher, showing that his ticket had cost the state $1,176. “Comparison for what our agency would have incurred,” another handwritten note says.

Eight days after the abortion hearing, Paxton called Roy and Castle individually into his office and gave them a choice of resigning or being fired. They resigned. And the departures set off a cascade of more bad publicity. There were repeated stories about how one senior staff member after another was fleeing an attorney general’s office that appeared in turmoil. Even worse, Lauren McGaughy, of the Dallas Morning News, reported that several staffers, including Roy, were still receiving their salaries weeks after they’d left the agency. The agency said that Roy and Castle had been put on “emergency leave,” a provision usually reserved for health and family emergencies. There were rumors that the emergency leave pay was used improperly as hush money for Roy and Castle, though both have told the Texas news media that they received only money that they were owed. The controversy prompted a legislative inquiry into the practice of using emergency leave as de facto severance pay, which isn’t permitted for state employees. Paxton had bungled his way into another public relations disaster, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Paxton gave his first major speech after he took office to the First Liberty Institute, a nonprofit that offers pro-bono legal support for Judeo-Christian groups or individuals who believe government has trampled on their religious liberties. This was fitting. Paxton has a long history with the Plano-based group, crediting First Liberty president Kelly Shackelford with convincing him to enter politics, in 2002. In that first speech, Paxton played to religious fundamentalists’ fears of being victims of the tyranny of the majority and of a godless government. Paxton said those who believe in religious liberty should stand against “mob rule” and referred to a “pop culture noise machine” on issues like same-sex marriage. “Our Founding Fathers correctly understood that a government that mandates one opinion over another is tyrannical,” Paxton said. The speech was also a bit of foreshadowing, because by the second year of Paxton’s administration, the attorney general’s office had started looking like a branch of First Liberty.

When more than 150 lawyers signed on to a grievance with the State Bar of Texas against Paxton because of the confusion he’d caused after the Supreme Court’s same-sex marriage ruling, it was First Liberty general counsel Jeff Mateer who came to his aid, writing op-eds in the state’s newspapers defending Paxton. (The grievance was eventually dismissed.) When Paxton was indicted, it was Midland oilman Tim Dunn—a member of the First Liberty board of directors—who wrote an editorial claiming Paxton was the victim of a conspiracy because he had once dared to challenge the reelection of Speaker Straus. Dunn had also helped Paxton win the attorney general’s race by guaranteeing a $1 million loan to his campaign through Dunn’s Empower Texans political action committee.

After the ouster of Roy and Castle, Paxton turned to First Liberty to fill the vacancies. He hired Mateer as his first assistant to replace Roy. Paxton initially employed First Liberty chief of litigation Hiram Sasser as his chief of staff in the position left open by McNamee’s departure, but Sasser soon returned to his old job because of family health issues. As Castle’s replacement as communications director, Paxton named management consultant Marc Rylander, who had until recently been a pastor at Prestonwood Baptist Church. (In 2003 Rylander wrote a letter to the Morning News chastising the paper for publishing same-sex commitment ceremonies, calling it a “journalistic compromise and tasteless submission to the homosexual agenda.” Rylander went on to write, “The thought of a homosexual couple does not stir animosity in me. But the idea of that couple being recognized and honored in your paper is appalling.”) It was unprecedented for a Texas attorney general to name the general counsel of a religious advocacy group as his top lieutenant and a pastor as his spokesperson.

“General Paxton has demonstrated antipathy toward the separation of church and state,” said Kathy Miller, the president of the left-leaning Texas Freedom Network. Paxton is “charged with upholding the law”; instead, she said, he is trying to undermine it. But one of Paxton’s longtime friends from the Legislature—Republican representative Dan Flynn, of Canton—said many people of faith in Texas agree with Paxton and his agenda. “We believe in protection of life. We believe in traditional family values, strong advocates of the Constitution,” Flynn said. “We believe in states’ rights, believe in the Second Amendment. All those issues that are important to Texans.”

Probably nothing was more symbolic of Paxton’s position on LGBT issues than the hiring of Mateer from First Liberty. The nonprofit pushed the idea that an individual’s constitutional liberties trump what they see as society’s changing morals and sensibilities. When Plano adopted its anti-discrimination ordinance, Mateer opposed it and threatened a First Liberty lawsuit against the city on behalf of any business fined under it. Before he became the top lawyer in Paxton’s shop, Mateer had represented Sweet Cakes by Melissa, an Oregon bakery that had refused to make a wedding cake for a lesbian couple.

Miller said that Mateer doesn’t believe in the separation of church and state. The Freedom Network has noted that at conferences Mateer often holds up a $100 bill and says he will give it to anyone who can find the words “separation of church and state” in the Constitution. “So a fundamental principle of our nation’s founding is something he denies,” Miller said.

At a basic level, Mateer is correct. The words do not appear in the Constitution but instead are drawn from an 1802 Thomas Jefferson letter, which the Supreme Court cited in 1878 to uphold laws against polygamy. “To permit this would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and in effect to permit every citizen to become a law unto himself,” the court wrote. Even the early Texans believed in the separation of church and state, mainly because of having lived under state-mandated Catholicism when a part of Mexico. As Texans prepared to join the Union, in 1845, the founder of Paxton’s alma mater, R. E. B. Baylor, convinced his fellow Texans that the first state constitution should prohibit members of the clergy from serving in any executive or legislative office: “It seems to me further that it is calculated to keep clear and well defined the distinction between Church and State, so essentially necessary to human liberty and happiness.” Mateer, however, said he draws on a U.S. Supreme Court dissent written by Justice William Rehnquist, “who said Jefferson’s phrase separation of church and state is a misleading metaphor . . . I want to keep minimal federal government out of religion.”

The ties between Paxton and First Liberty are financial too. Because the criminal case against Paxton involves his private law practice, he cannot use campaign funds to pay for his defense, and any money he raises personally must be free of conflicts of interest with the attorney general’s office. When Paxton accepted a $1,000 gift from First Liberty president Shackelford and his wife, it was listed on Paxton’s public disclosure forms as “gift . . . from family friend who meets the independent relationship exception,” although there is anything but an independent relationship between Paxton and Shackelford’s institute.

Perhaps the most revealing examples of Paxton’s close relationship with First Liberty are the five occasions in which he has used the prestige of his office to support the group, filing friend-of-the-court briefs in favor of First Liberty clients. While such amicus briefs are really more of a political statement, they can boost the chances a court will take a case seriously, especially when that brief comes from a state attorney general. Two of the briefs involved religious nonprofits that objected to filling out waiver forms so they would not have to pay for contraceptive insurance for employees under the Affordable Care Act. Though one pertained to Texas nonprofits, the other was on behalf of the Little Sisters of the Poor, a group of nuns located in Denver. On another occasion, Paxton filed an amicus on behalf of a Marine at Camp Lejeune, in North Carolina, who was receiving a bad-conduct discharge in part for posting a Bible verse in a work space she shared with another Marine and refusing an order to remove it. Closer to home, Paxton also supported First Liberty’s challenge to the Kountze school district over a one-time ban on cheerleaders’ putting Bible verses on banners at football games. A district judge was prepared to dismiss the case because Kountze ISD had dropped its objection to the Bible verses, but First Liberty and a private attorney representing the cheerleaders’ families appealed to the Texas Supreme Court. A favorable Supreme Court ruling in the case not only set the stage for a permanent injunction against the school district but also opened the door to the possibility of First Liberty’s obtaining attorneys’ fees from the district’s insurance policy.

But it’s a case in El Paso that raises the most-troubling questions about Mateer’s presence in the attorney general’s office. The suit began with Mayor John Cook’s backing a nondiscrimination ordinance, which led to an effort to recall the mayor spearheaded by Bishop Tom Brown and his Tom Brown Ministries and Word of Life Church. The recall vote failed, and Cook turned around and filed a lawsuit alleging that Bishop Brown violated state campaign finance law during the recall election by utilizing forbidden corporate money.

Before joining Paxton’s staff, Mateer represented Brown in the case on behalf of First Liberty. And, in another interesting twist, the court had once asked then–attorney general Abbott’s office whether it wanted to become involved in the case, and Abbott’s staff declined.

But after Mateer joined the staff, Paxton’s office suddenly got involved in the case, writing a letter to an El Paso court asking it to reconsider federal campaign finance laws before awarding damages. The case was settled in May. Mateer said he had nothing to do with the El Paso filing and that he had immediately recused himself once he learned about it. “I had no discussions with anyone, so I don’t know how it came in,” he said. But an email obtained through the Public Information Act shows that Dave Welch, the head of the U.S. Pastor Council, had contacted Mateer and another Paxton aide, asking them to intervene on Brown’s behalf.

Cook’s attorney, Mark Walker, said the filing was suspicious because of Mateer’s previous involvement in the case. “It’s outrageous. I don’t care what your political leaning is, I just want you to follow the law,” Walker said. “I’m concerned about over-politicization of the [attorney general’s] office, and I’m a pretty conservative person.”

By the time Mateer and Rylander joined the staff in early 2015, the public perception of Paxton couldn’t have been much lower. Newspapers in Austin, Corpus Christi, Houston, and Longview had called for his resignation, while the Morning News and the San Antonio Express-News urged him to step aside until his criminal case could be resolved. Paxton, still backed by his core supporters, was unmoved. “Anybody remember how many papers endorsed me when I was running against a Democrat?” he asked a crowd of partisans. “The answer is none. So is it shocking to me that they’re not helping me right now?”

Still, he hired not one but two crisis-management public relations firms in March, and slowly they began to work to rehabilitate his image.

One of the firms was the Dallas-based Spaeth Communications, which, according to agency documents, was paid $2,529 by the attorney general’s office. The other was CRC Public Relations, an Alexandria, Virginia, company, which was paid $19,500 from Paxton’s campaign account. The two Republican firms were familiar with each other. They had worked together in 2004 to organize and promote the controversial Swift Boat Veterans for Truth group that attacked Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry.

The Dallas firm’s owner, Merrie Spaeth, had been the director of media relations in the Reagan White House. She had also coached special prosecutor Ken Starr for his presentation to the House during the impeachment of President Bill Clinton. And most recently she had been advising Starr in his handling of the media in the rape scandal that occurred while he was president at Baylor University. (By coincidence, in January Paxton protected Baylor from having to release campus police reports on one of the rapes, citing common-law privacy even though the victim already had identified herself on ESPN.)

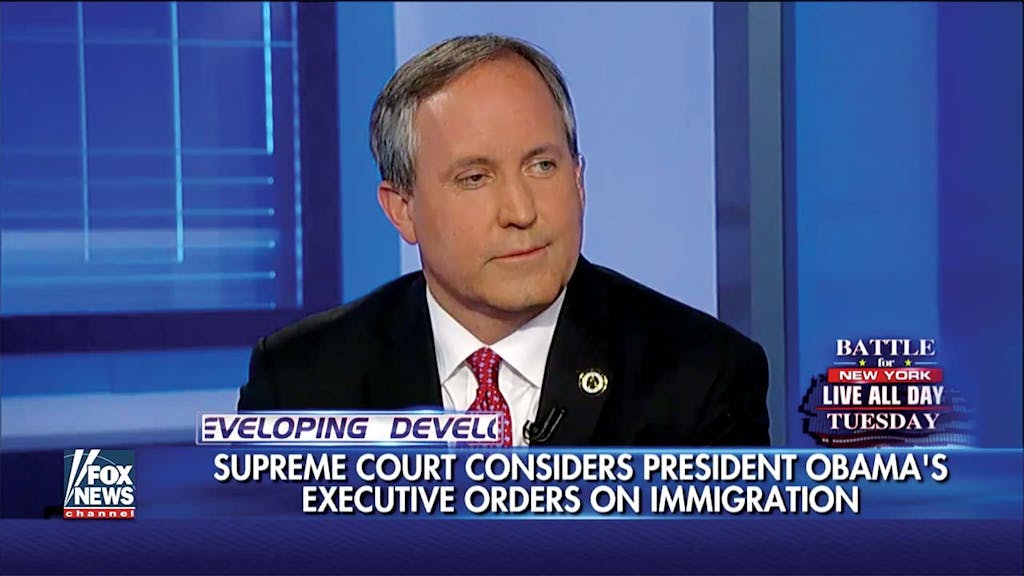

Paxton’s PR investment soon showed results. Six weeks after Castle’s staff had been unable to get Paxton any national media interviews, he suddenly had a flurry of exposure around the state’s arguments to the Supreme Court against Obama’s immigration policies, including interviews in New York with CNN and Fox News. Solicitor general Keller was again representing the state, but this time it was Paxton in the limelight.

In April Paxton shared the stage with Keller during an appearance on Greta Van Susteren’s On the Record, on Fox. After throwing a softball question to Paxton, Van Susteren made a point of noting for her viewers that Keller was the lawyer arguing the case. She would do the same thing again in June, when the two men appeared on her show by satellite feed after Texas won a Supreme Court ruling that upheld an injunction against the Obama immigration plan. Paxton might not have been the lawyer arguing the case, but he was going to play one on TV.

Though Paxton’s staff changes may have resulted in his receiving more positive press, they also weakened the barriers that traditionally separate state business from overtly partisan politics. For instance, Rick Perry’s policy as governor—including when Castle was on his staff—was to use campaign or private funds for travel to avoid any chance that taxpayers would cover the cost of politicking. When Abbott took over the governor’s office, he adopted the same policy. But after Castle left Paxton’s office, things changed rapidly.

The most egregious blending of state business with politics at taxpayers’ expense occurred on a June trip to the nation’s capital. The dates of the trip coincided with the Faith and Freedom Coalition’s Road to Majority conference, where Paxton spoke on the final day. Paxton made the trip with Mateer, Rylander, and Smith.

Paxton tried to work in some state business. On the first morning in Washington, he held a news conference on the steps of the Supreme Court to announce that Texas was joining a 21-state lawsuit against Delaware for keeping unclaimed funds from a national check-writing service. But that hadn’t been the point of the trip. In fact, the news conference had been added to his schedule at the last minute, and Rylander admitted it was held in Washington only because Paxton was already going to be there on other state business. On the day after the news conference at the Supreme Court, Paxton gave a speech at the Heritage Foundation on climate change litigation involving Exxon. But besides that speech, Paxton’s schedule had numerous undocumented hours.

The Road to Majority conference is a Christian conservative political gathering that featured speeches by various Republican candidates, including GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump. Also coinciding with the trip was a filing by his Washington-based lawyers challenging a civil suit—separate from the criminal prosecution—filed against him by the Securities and Exchange Commission over his Servergy work. Paxton’s lawyers did not respond to inquiries about whether he met with them during the trip.

Paxton’s own request for travel for the three days shows that the original reason for going to Washington was “for speaking event, ‘Think Tank,’ presented by Road to Majority.” But when he tweaked his travel plans on June 1, all mention of Road to Majority vanished from the travel requests for him and his entourage, becoming instead a simple “speaking event,” though the dates of travel continued to overlap with the political event. The Road to Majority organizers posted photographs on Facebook of Paxton speaking. Mateer’s expense report listed the speech as “state business.” The total cost to Texas taxpayers for the four days of travel for Paxton and his three aides during the political gathering exceeded $7,800.

Paxton didn’t use state funds to attend the July Republican National Convention, in Cleveland, but there too he took every opportunity to appear before an audience or a camera, even sitting for an interview with MSNBC.

Paxton spoke to Texas delegates in a hotel ballroom on the morning of the convention’s third day. Angela, who has much more stage presence and charisma than her husband, introduced him, as she often does at events, by singing a ditty she’d written in which she declares herself a “pistol-packin’ mama” whose “husband sues Obama.”

The attorney general received a warm ovation from the party faithful. “I was on Fox News last night,” Paxton gleefully told them. “I just wanted to see how many of y’all stayed up to watch me at 2:05 a.m. this morning.” Everyone laughed, and Paxton seemed to be gently making fun of himself.

But then you do have to wonder: Who exactly goes on television in the middle of the night? In this case, a politician trying to beat an indictment. Part of his strategy seems to be appearing on television as often as possible, and it’s hard to argue with the results. His indictment is barely even mentioned anymore during his TV appearances, and he’s rarely asked about it.

When Paxton was first indicted, his political career seemed in shambles, and there was rampant speculation that he would resign, especially after he shrank from the spotlight. But his public reemergence and his television offensive make his political survival seem like a real possibility.

His trial in Collin County is expected to begin in the coming months. Even if he’s convicted of the felonies, it’s not clear that Paxton would immediately be forced from office. He would likely be disbarred, but he could still carry on; there’s no requirement in the state constitution that the attorney general have a law license. Moreover, state law is murky on whether a convicted felon can remain in office. On the other hand, if Paxton is acquitted, he would once again be tough to beat in a Republican primary, and with Democrats offering only token resistance in the general election, he’d be likely to win another term, in 2018.

On that count, he can draw inspiration from the last sitting Texas attorney general to be indicted, from another time and another party: In 1983 Democrat Jim Mattox was charged with abusing his office. As with Paxton, many Austin insiders thought his political career was over. But Mattox persevered. He was later acquitted, and in 1986 he won reelection.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Ken Paxton

- Austin