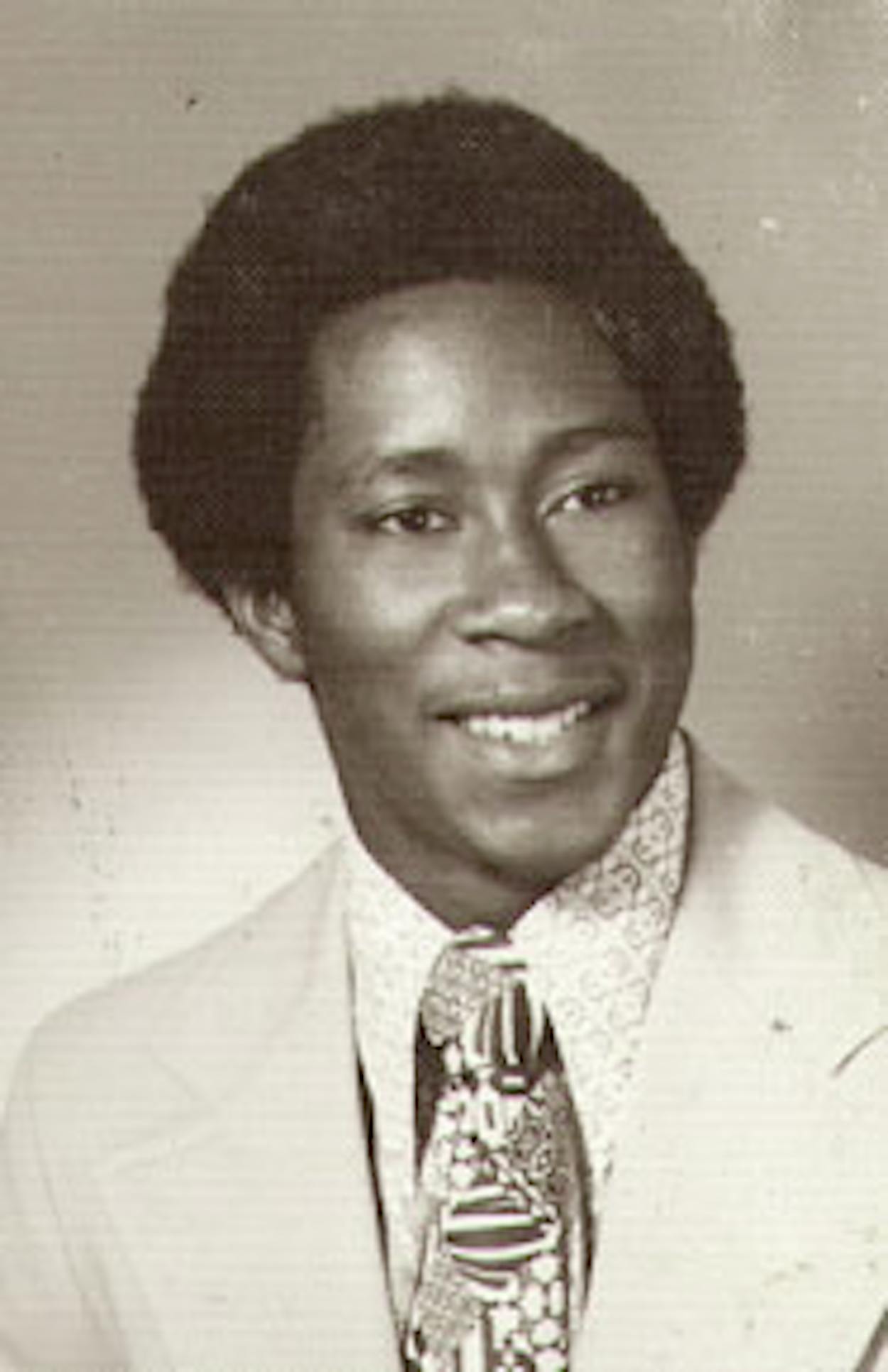

Midway through his second year at Austin College, Ron Kirk suffered the painful identity crisis of a young black man making his way in a white world. On the mostly white campus in Sherman in 1974, Kirk felt adrift from the African American friends of his youth and the familiarity of his East Austin neighborhood. He left school, went home, and announced to his father that he needed time off from college to find himself. Lee Kirk’s response was unsympathetic: “You can find a damn job!”

But in later conversations the father talked to his son about the hard lessons of race. As Kirk remembers it, “My dad said, ‘It’s a real tragedy—all you have to do for a white person to know you are black is just open the door and let the sun hit your face.’” But, he warned his son, there would always be some black people who would question his “degree of blackness” if he won success in the white world. During the next few months, while Kirk worked at the state capitol, he came to understand his father’s message: Don’t let race alone define who you are. “I finally realized you are a product of everybody who has been in your life, and that person is fine,” he says now. “I got this sense that I didn’t need to meet everyone else’s expectations of blackness. It liberated me. I was who I was.”

Being who he is has taken Kirk a long way—first, to two terms as mayor of Dallas and now, at age 48, to the Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Republican Phil Gramm. His battle against Republican attorney general John Cornyn looms as one of the nation’s closest and most important races. Not only is control of the Senate at stake but also the political prestige of George W. Bush, for whom the loss of a seat in his home state would be devastating. Early polls show Kirk running anywhere from a little behind Cornyn to a little ahead. And yet, as the campaign heats up, Kirk faces a familiar problem. The very thing he prides himself on—that he’s not the kind of person who can easily be stereotyped or pigeonholed—runs counter to the conventional wisdom of how to win an election: A candidate must define himself or run the risk of having others do so.

The latter is exactly what is happening. That door his father spoke about has swung open once again to illuminate the color of his skin. While Kirk is running a race of politics, friend and foe alike seem to want to talk about the politics of race. To the media, he is the first African American to seek a major statewide office in Texas. To his own party, he is—along with gubernatorial nominee Tony Sanchez—part of a Dream Team that will energize the party’s dormant core constituency of ethnic minorities. To Republicans, he is part of a cynical Democratic effort to assemble a ticket based on race instead of leadership and qualifications: “Is it a ‘dream’ because their candidates are proven leaders? No,” said Gramm at the Republican state convention in Dallas earlier this summer. “The Democrats believe they can divide Texas based on race.” Democrats fired back a week later from their convention in El Paso: “Republicans have launched a very cynical attack of division that essentially says to Texans that a qualified African American is not fit to run for the Senate,” said Molly Beth Malcolm, the state party chair.

More than a quarter century after wrestling with his racial identity as a college student, Ron Kirk again finds himself struggling to explain who he is. This much we know: He is a member of the last generation of blacks to live under Jim Crow laws and the first to enjoy post-segregation opportunities. His career is a mirror of his time: His boyhood ambition was to be a civil rights crusader, but over the years he has gravitated toward politics—first as a staff member, then as an appointed official, then as an elected official whose policies were closely aligned with the wish list of the rich and the powerful. He has a sunny personality and a quip-cracking style. But as for what he believes and how he would vote on the great issues of the day—including all the civil rights issues, from affirmative action and reparations to redlining—he has had little to say. Sometime in the next few weeks, Ron Kirk is going to have to decide: Is his best chance to win the Senate race by running as a black politician or as a politician who, among other things, is black?

KIRK ARRIVES AT THE DEMOCRATIC STATE CONVENTION HALL in El Paso in mid-June amid an atmosphere of great expectations. To overcome Cornyn’s advantages of a nearly $15 million campaign war chest and the president’s strong support, he will have to generate excitement as well as campaign contributions; he will have to become what political pros call a rock star, someone who can incite an audience with the electrifying aura of celebrity. So far, so good. The crowds in El Paso jam in around him so closely that he can hardly move. Even in the huge arena he is easy to spot: His solid six-two frame, topped with a gleaming brown dome, bobs and weaves in a mass of well-wishers. Dressed in a black pinstripe suit, his signature round wire-rimmed glasses framing a relentlessly cheerful face, Kirk shows off his cuff links, a pair of silver dancing stick figures, one adorning each crisp white sleeve. “That’s Mr. Happy Man,” Kirk explains. “Just like me.”

Right now, Mr. Happy Man is late for a speech, despite the best efforts of a cadre of youthful campaign aides trying in vain to push him through the crush. Every few steps, a shriek of recognition goes up, and Kirk is battered back by the next wave of admirers. He recognizes many of them, or knows how to make them think he does; he greets each one with a bear hug, rocking back and forth as he booms his greetings: “You look so goood! How have you been? How are your babies?” His voice has the resonant quality of the high school choir baritone he once was.

But when a TV reporter shows up, Mr. Happy Man turns into Mr. Mayor. No matter what the question is, he turns the answer into an opportunity to deliver his spiel. The reporter wants to know whether he supports Bush’s tax cuts and if he favors more. Kirk responds that he believes tax policy should be related to the economy. “Look at my record as mayor of Dallas,” he says. “Times were good, we were flush with cash, and we returned money to the taxpayers four times.”

This is standard political procedure, but it suggests a problem for Kirk: How can he project his personality on TV? In the Democratic senatorial debate with rivals Ken Bentsen and Victor Morales, he was almost grave. He seemed to be deliberately holding his lighter side in check. It’s easy to be a rock star at a Democratic convention, but these days races are won and lost on television.

Finally he works his way to the podium for his speech. “I’m sorry I’m late,” he tells the assembled Democrats. “There’s just too much love, too much energy in this convention hall. We need to bottle it and open it up in September. We’re well positioned in the polls, but we have to do the work to win.” Like all convention speeches, this one is mainly a pep rally for the faithful, and then off he barrels to the next appearance on his schedule. About a hundred supporters are waiting for him, waving campaign signs, whooping and applauding. For the next hour, Kirk is awash in volunteers promising to work for him (“Oh, bless your heart!”), asking him to pose for pictures (“I’d be honored to!”), or recounting their endeavors during his primary campaign (“Tell me your name. Where are you from?”). His face is alive with interest; his responses are energetic. He maintains physical contact: a touch on the shoulder with men, holding hands with women. If a picture is requested, he flings his arms open and hugs people close for the pose. The crowd is an eclectic mix of aging hippies, labor guys in union gimme caps, and the proverbial little old ladies in tennis shoes. Spotting a woman in a wheelchair on the edge of the crowd, Kirk pushes past several people and leans down to shake her hand. Another woman shouts above the din, “I don’t know if you know this, but you have brought excitement to the Democratic party!” Mr. Happy Man is beaming.

The mood is more somber at the El Paso Youth Tennis Center, which Kirk, trailed by the omnipresent TV cameras, visits during a break from the convention. The center, a partnership between the city and the private sector, rewards athletes who stay in school with college scholarships. About 75 squirming, sweating kids have gathered under a shaded patio to hear Kirk praise the program while the camera crews grind away. “We’re doing this because we love you boys and girls,” he says. “All this helps you be a better person.” Once again, when the camera turns on, Kirk seems to turn off. Afterward, he is signing tennis balls when a handsome thirteen-year-old Hispanic boy confesses that he has dropped out of school. Kirk’s pen freezes in midair. “Uh-oh,” he says. “Come on over here.” They walk over to a picnic table away from the crowd. He sits next to him, leans his face close to the boy’s ear, and drops his voice to a whisper, his forehead furrowed with intensity. Later, I ask him what he said. “I just wanted to tell him not to be afraid to go back,” he says. “Don’t let being macho or embarrassed keep him from going back.”

When the media event is over, he steps into the sun for his umpteenth television interview of the day. “I glow like a lightbulb when you get me out of the shade,” he jokes to the interviewer while he mops his bald pate. Then it’s back on camera and on message. “It’s not enough to tell kids to just say no,” he says. “We have to give them something to say yes to.”

IN KIRK’S OWN LIFE, what he had to say yes to was, most of all, his mother. Willie Mae Kirk, now eighty, still lives in the unimposing brick house on Austin’s east side the family moved to when Ron was around ten. His father died in 1982. Unlike the house, she is imposing. Sitting in her immaculate family room, she leans back in her chair and gives me a look perfected by 32 years of teaching fifth graders. “Don’t argue with your kids,” she says. “You have to mean business. I stuck to my guns. When I’m ready to go, you be in that car. I’d go off and leave them in a minute. If you start talking, you’re lost.”

It is apparent that Willie Mae Kirk is never lost. Through segregation, through her husband’s slide into alcoholism, through the civil rights revolution, she maintained a home of strict discipline, strong neighborhood ties, and high expectations for her children. She grew up in nearby Manor, the next to last of fourteen kids. Orphaned when she was twelve, she was raised by a sister in Austin. After she graduated from high school, she marched into the president’s office at Sam Huston College (today, Huston-Tillotson), a small all-black school a few blocks from her sister’s home, and announced that she couldn’t enroll without financial aid. She got a scholarship that day. At school she met Lee Kirk, and they soon married. World War II had begun, and Lee enlisted in the Army upon graduating. By the time he was transferred to Washington, D.C., Willie Mae was pregnant. After the war came a second daughter, then two sons (Ron is the youngest). Lee had ambitions to go to medical school, but they were shelved as his young family grew. Instead, he went to work at the post office, where he was the first black mail clerk in Austin. But, Willie Mae adds, he was passed over for promotions because of his race: “They just weren’t going to have a black supervisor.”

The humiliation, she says, led to her husband’s alcoholism. Lee Kirk’s acumen in math and science had won him admission to Sam Huston at age fourteen, but it couldn’t get him a promotion. His kids never saw him drunk. Whatever effect it had on the family, Kirk keeps to himself. “My father was an alcoholic who never missed a bill,” he says, “never missed a day’s work.”

Both Kirks became leaders in the emerging civil rights struggles of the fifties and sixties. Saundra, the eldest of the children, remembers the day she was called to the principal’s office with the five other black students at her junior high and told she would be getting a day off from school. The rest of her ninth-grade class, which by that time was integrated, was going swimming at Barton Springs, which was still whites-only. “We reported it to our parents,” Saundra remembers. “My father and the other parents went to school. It was determined we would be allowed to swim.” Saundra and the other black kids became the first non-whites to swim at Barton Springs. Her mother was so excited that she bought her a brand-new bathing suit.

Eventually Ron would become one of the first black lifeguards at Barton Springs, but before that he had his own brushes with segregation. Once, around the age of eight, he attended a movie at the Paramount Theatre downtown. “The black kids went upstairs to the balcony, and there was an elderly gentleman with a little crate who would sell us snacks,” he recalls. “And I said, ‘Isn’t this neat that we don’t have to go downstairs and get in line for our snacks?’ My brother said, ‘You are an idiot. You can’t go downstairs.’”

He remembers the East Austin of his childhood as a close-knit community, a place where his family helped build his uncle’s church by hand—Ron toted cinder blocks, a cousin laid the concrete. The community had its own special rituals, like the Saturday morning trip to a nearby barbershop; if any of the kids had achieved something, Clyde the barber would tell everybody about it. “I remember how special it was to get into that chair,” he says. “You had the attention of the neighborhood on you for fifteen minutes.” Saundra describes the neighborhood as intimate. “We were close to the parents of our friends,” she says. “I accepted their discipline and values and code of conduct. People were not afraid to tell somebody else’s child how to behave.”

Willie Mae had an open-kitchen policy. Neighborhood kids ate there, as did visiting black entertainers. Ron remembers that the Supremes were Willie Mae’s guests; Saundra still has a photo of Louis Armstrong, another guest, which he autographed. On Sundays Willie Mae would send her children out with plates of food for elderly neighbors. In the summers she worked as a playground supervisor and often brought home children who had no lunch. “Sometimes I would have to split one wiener down the middle to put between two buns to provide for everyone,” she recalls. “I didn’t have to say to my kids, ‘You must share.’ They saw it growing up.” Stuart King, a childhood friend who now operates a mortuary in East Austin, says, “He was always doing stuff for kids who didn’t have school supplies, didn’t have lunch money. This was even in first and second grade.” This practice proved useful, says King, when Kirk began his political career in the sixth-grade race for student council president: “We took candy to all the kids to vote for Ronald, and he won.”

But change was coming to East Austin, as it was coming to every black neighborhood in America in the sixties: school integration, civil rights laws, school busing, riots in the urban ghettos, black power, and issues of racial identity. In junior high Kirk was thrust from his cocoonlike world when his parents sent him across Interstate 35 to University Junior High, on the UT campus, where the student body was one third Anglo, one third black, and one third Hispanic. “We had the riot of the week,” says Kirk. “One week the whites and Hispanics would beat up the black kids, the next week it was the whites and blacks beating up the Hispanics.” Things weren’t any easier when he returned home. “The kids from Kealing [the all-black neighborhood junior high] picked on us for going to school with white kids. At school we were too black for our classmates, and then all of a sudden, we weren’t black enough. They said I ‘talked white.’ I said, ‘My mother’s a schoolteacher; I have no choice.’” Those years, Kirk now says, “were an important journey for me. I learned that good friends were special enough that you ought not to be preoccupied with the package they come in.”

In high school Kirk was active in the choir and student government. He was elected president of his senior class, and friends like Stuart King were convinced that politics was his future. But Kirk had something else in mind. Growing up black in the sixties, he saw that the main agent of social change had been the courts. “From ninth grade on, I wanted to be a lawyer,” he says. He wanted to be a “civil rights crusader,” like his hero, Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP lawyer who had argued the school integration case before the Supreme Court and later became its first black justice. The law was where the power was. “Do you remember the old sixties joke?” Kirk asks. “What’s the difference between the KKK and the Supreme Court? The Supreme Court wears black robes and scares the hell out of white people.”

HE CHOSE AUSTIN COLLEGE because it had a strong reputation for preparing students to go on to professional schools and because he wanted to travel a different path from his siblings, who had gone to UT and Texas Southern University. On the first day of school, he went to the gym and met two other freshmen, one Hispanic, the other white, in a pickup game of basketball. For a time they were inseparable, but then the identity crisis of his sophomore year led to his return home. “I felt like I was in two worlds,” Kirk says now. “I was alienated from my black friends.”

His father’s insistence that he find a job led Kirk to politics. Thanks to the recommendation of a family friend, he was hired by Austin lawmaker Sarah Weddington, who had successfully argued Roe v. Wade before the Supreme Court, the landmark case that established a woman’s right to have an abortion. Returning to the Capitol from whose bathrooms he had been excluded as a child, Kirk got to know some of the powerhouses of Texas politics. He met Mickey Leland and Craig Washington, two black lawmakers from Houston who went on to be elected to Congress. (He still keeps a large portrait of Leland, who died in a plane crash in Africa in 1989, in his Dallas law office.) And he became friends with Weddington’s savvy, wisecracking office manager—a woman named Ann Richards. He also managed to earn credit through a work-study program at Austin College. After a semester off, he returned to Sherman to finish school. But for Kirk something had changed: “I fell in love with politics.”

In doing so, he moved away from the Thurgood Marshall career track of the crusading lawyer; he was less and less engaged in principle and more and more engaged in process. Two events occurred while he was at UT Law School that accelerated this trend. The first came when he was tapped to play on the Legal Eagles intramural football team, coached by the renowned constitutional law scholar Charles Alan Wright. When the Eagles won a game—and they have seldom lost in their 47-year history—Wright would reward the players by taking them out for a cold beer. Formidable in the classroom, Wright was almost like a father in those post-game sessions. Austin attorney Mike McElroy, a friend and Legal Eagles teammate of Kirk’s, says that the experience gave the team members intellectual confidence. “You could cut up and tell jokes and Wright was in the thick of it,” McElroy says. “You learned you could be around people like him and hold your own.” Kirk calls Wright “an awesome man. I was blessed to be part of his family.”

The second formative event was working during law school at the House Study Group, a nonpartisan legislative staff group charged with analyzing legislation for House members. McElroy was there too. “Our job was simply to give legislators pros and cons and let the Legislature make up its mind,” he recalls. “Ron undoubtedly gained from that. It’s important in politics to understand where the other side is coming from and to hold discussions in a way that makes people want to continue to talk. He learned that skill.”

A chance conversation in a Capitol elevator in 1979 put Kirk on the path to Dallas. State representative David Cain, now a state senator, asked him to join the law firm he was starting up. But Kirk missed politics. After two years in private practice, he joined the staff of U.S. senator Lloyd Bentsen in October 1981. There Kirk learned that the lesson his father had taught him about race—you have to be comfortable with who you are—could also be applied to politics. Bentsen was wealthy and patrician; he had defeated incumbent Democrat Ralph Yarborough, the darling of the liberals, to reach the Senate, and most Democrats, left and right, expected him to continue the factional warfare that had divided the party for two decades. Instead, Bentsen unified the party and became a national figure. “Lloyd Bentsen never tried to live up to other people’s expectations of him,” Kirk says. “He was a different type of Texas politician. Some people would easier understand him in the House of Lords. I’ve got some blue jeans and a work shirt and some boots I could scuff up, but that would be a made-up image. Voters are smarter than that. You’ve got to be comfortable with yourself.”

He returned to Dallas in 1983 to join the city attorney’s office and drew the assignment of lobbying for the city’s interests before the Legislature in Austin. In the summer of 1984, he went to a charity banquet and found himself sitting next to a woman named Matrice Ellis. One conversation centered on Vanessa Williams, the first black Miss America, whose reputation had been marred by the publication of nude photos. “Everybody at the table said she should resign,” Kirk says. “Matrice took the argument against that. I was impressed that she was not only articulate but strong enough to stick to her convictions,” Kirk says. “What I should have known was that she is just hardheaded. She thought I was loud and abrasive. Can you imagine that?” Three years later they were married. Today they have two daughters: Alex, age thirteen, and Catherine, ten.

Kirk lobbied for Dallas until 1989 and then joined Johnson and Gibbs, a large downtown firm. Once again, however, the pull of politics was irresistible. Ann Richards, the former office manager from his first Capitol job, had been elected governor in 1990, and she soon named him chairman of the board that oversaw the purchasing agency for state government. Later she made him Secretary of State, the most prestigious appointive job in state government, and one that is frequently a stepping-stone to high office.

That office, of course, turned out to be mayor of Dallas. Kirk came to prominence during a period when the city was beset by racial divisions on the city council and the school board. The business leadership, still a potent force in Dallas, came to the conclusion that the time had come for the city’s first black mayor. It gave its blessing to Kirk. He won in 1995 with 62 percent of the vote, defeating a large field without a runoff.

BY ANY MEASURE, HIS TENURE as mayor was a huge success. Unlike Houston, Dallas does not have a strong-mayor form of government; a professional manager oversees the bureaucracy, and the mayor is a part-time, nonpartisan official who wields power mainly by persuasion. (His new law firm, Gardere, Wynne, and Sewell, paid him $227,000 a year, though he worked only a few hours a week.) Nevertheless, Kirk was able to get just about everything he wanted. His brook-no-nonsense style brought an end to the racial bickering on the council. He pushed through two major projects backed by his business constituency: $125 million in public revenue for a downtown sports arena, a private venture whose owners at the time included Ross Perot, Jr., and radio mogul Tom Hicks; and a $543 million bond package, which included funding for the long-sought Trinity River development project, encompassing flood control, freeways, and parks. Both projects had to be approved by the voters, no easy feat, and both were. (The sports arena is in operation, but Kirk’s plan for the Trinity project has been stalled by lawsuits and opposition by Kirk’s successor as mayor, Laura Miller.) When suburban officials threatened to lead their towns out of the DART light-rail system, Kirk turned on the charm and persuaded them to stay in. Voters rewarded him at the polls by reelecting him in 1999 with more than 74 percent of the vote.

Still, he was not without his critics. Laura Miller, who had been the city hall reporter for the alternative newspaper, the Dallas Observer, led the opposition during Kirk’s second term as mayor. (Miller declined to be interviewed for this article.) An ally of Miller’s on the council, Donna Blumer, blames Kirk for heavy-handed treatment of council members who questioned his initiatives. Her poor relationship with Kirk began on his inaugural day, when she and four other council members voted against his choice for mayor pro tem. “From that day on,” she says, “he declared war. He denied us committee chairmanships and froze us out. He can turn on the charm when he wants to, but he is a very vindictive man.”

Much of Miller’s and Blumer’s criticism of Kirk was based on his support of public funding for private projects. “There was no need for any public funding of the sports arena. It is corporate welfare,” Blumer says. “The mayor encouraged the city to cut a deal that was so one-sided, anybody could see it was a rip-off of the taxpayers.” Kirk defends the deal, saying the city was competing against suburbs in enticing the developers to select downtown Dallas as the site for the new arena. “You have to strike the very best deal you can, and we did that. We capped our investment, and when the project grew from $250 million to $430 million, the city’s contribution never increased one bit.” He credits the arena with drawing nearly three million visitors a year to downtown Dallas. “That’s the way you make your downtown viable. You invest.”

Blumer also notes that former city manager John Ware, “who was very tight with the mayor,” left the city and went to work for Hicks shortly after the arena deal was reached. Kirk acknowledges the timing “looked bad” but defends Ware’s participation in the arena negotiations: “I can tell you from having been there that he was hard-nosed and kept his eye on the bottom line.” Hints of impropriety with Hicks hit closer to home when the Dallas Morning News revealed that Matrice Kirk, a University of Pennsylvania graduate who had worked for the trust department at a bank and later became the budget director of DART, served on the corporate board of one of Hicks’s companies. Kirk points out that at the time his wife joined the board, Hicks didn’t own the company. “She went on the board with a private company with zero relationship with the city, the Mavericks, or the Stars at a time when Tom Hicks didn’t own it,” he says. “But I’m not nuts. It looked bad and she resigned. She did the right thing, and I’m proud of her.”

Although Miller and Blumer seldom won a battle with Kirk—one exception was a battle to keep aging neighborhood pools open—Miller was able to exploit resentment over tax subsidies to win the mayor’s job in January after Kirk stepped down to run for the Senate. Kirk endorsed her main opponent, local businessman Tom Dunning. “She came in with the idea that she was against Kirk,” says Dunning. “There is a natural resentment by populists. They don’t want to see any deals done with people who are considered rich—but Dallas won as a result of these deals.”

ANOTHER CITY, ANOTHER APPEARANCE. Several hundred Texas public school teachers have assembled at Austin’s Renaissance Hotel for the Texas State Teachers Association’s annual convention, at which Kirk is the featured speaker. Before he can say a word, the applause that greets him blooms into a standing ovation, complete with whistling and cheering. The energy seems to surprise him. “Daa-yumm,” he says, grinning. “It’s too bad y’all are in such a bad mood.”

He plows ahead with his speech, ending with a deft reminder that he is Texas’ first African American nominee for the U.S. Senate. “I’m here because someone dared to believe in me, because of people who saw a whole lot more than a busboy,” he said. “We need to tell a child, ‘I love you and you can do more.’” As the audience erupts in raucous applause, a throng gathers along Kirk’s exit path. “I’m a teacher and that was an A plus,” one woman gushes as she clasps Kirk’s hand. Another says that she works part-time at Neiman Marcus and waited on Kirk and his wife the previous summer. “I don’t know if you remember me,” she says, and he cuts her off with a quip: “As if I could remember everybody that waited on my wife at Neiman Marcus! Do me a favor, will ya? Next time you see her in there, you run her out!”

This performance is a balancing act of charm and substance that Kirk has been perfecting since his father admonished him at a young age: “Boy, you can’t get by on just charm alone.” He will need to find the right balance to have a chance to defeat Cornyn, whose biggest advantage in the Senate race comes from his support for—and from—President Bush. Kirk, the Republicans will argue, will support the policies of majority leader Tom Daschle and the Democratic left. They will try to draw him into a debate on issues that will highlight his differences with Bush. Kirk will respond as he did in El Paso, when a TV reporter asked him, “How do you feel about being on the Dream ticket?” Kirk’s answer: “That’s not what this election is about. It’s about what’s been happening in Washington for too long. There’s too much partisan bickering.”

Kirk’s immediate problem is money. With his financial resources depleted to around $500,000 after the Democratic runoff, he has spent most of his time trying to raise the $10 million or so he will need for the race. Before he can expect to get any help from the national Democratic war chest, he will have to show that he is competitive—both in the polls and in the ability to raise money. In the spring, statewide polls taken in Texas showed Cornyn with a lead of five to seven points, which is close to the Republicans’ built-in edge in voter loyalty. However, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee recently released the results of a sample of eight hundred registered voters that showed Kirk leading by 46 percent to 42 percent; an early summer poll conducted by Richard Murray of the University of Houston showed him with an even bigger lead.

But the campaign hasn’t really begun in earnest, and Cornyn’s strengths—money and the White House—have yet to come into play. A lot of things will have to go right for Kirk to win. Above all, he will have to be able to raise the money. “It’s tough,” he says. Next, he must find a way to keep Cornyn from turning the race into a referendum on the policies of Bush (or, equally bad, Daschle). Corporate cheating, the uncertain economy, and health care rank as the best issues for Democrats; the war and tax cuts are the worst. Then there are strategic decisions, starting with how he can find a way to get his personality to come through on television. The campaign must exploit his popularity in the huge Dallas-Fort Worth media market to woo some swing votes. A lot of Dallas Republicans crossed party lines in the spring to vote for Kirk—but will they do it in November? Finally, he must successfully define himself on the issue of race. We know he isn’t Al Sharpton or Jesse Jackson, but he has to establish himself as a centrist black Democrat. Is it possible to run as a black candidate in order to increase minority turnout and, at the same time, run as a candidate who, among other things, is black in order to get the 35 percent or so of the white vote that he will need to win? Ultimately, the color of his skin may decide the Senate race, but in which direction? Democrats need to play it up to increase their turnout. Republicans need to play it up to prevent Kirk from getting that magic percentage of the white vote.

The fascinating thing about the race is that each side must engage in racial politics, and yet there are big risks for each in doing so. You can’t apply a racial stereotype to Kirk, and here is a cautionary tale for those who would try. One evening while he was mayor, he was waiting for his car at a valet station following a Dallas charity event. He was dressed in a tuxedo, his wife next to him in a smashing dress, when a man walked up and tossed his keys to Kirk so he could fetch his car. Then, in Hollywood timing, the real valet pulled up with Kirk’s BMW. Still holding the man’s keys, he climbed in and drove happily away.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy