Politics can be complicated, replete with unending context and backstory. But underneath nearly every political dispute—from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to fallings-out at homeowners association meetings—are almost banal matters of self-interest, explainable in just a few words. The effort to overturn paid sick leave ordinances in Austin, San Antonio, and Dallas is just that simple.

Proponents say that the ordinances, which require businesses to give employees a certain number of paid sick days a year, make life better for workers, especially hourly employees. Opponents say the ordinances cost businesses money. Both propositions are true, so the question is which group’s interests matter more. Because business owners rank a lot higher than hourly workers in the Legislature’s Hierarchy of Friends, it’s been clear from the minute that the Austin City Council passed its ordinance last year that state lawmakers would try to crush it.

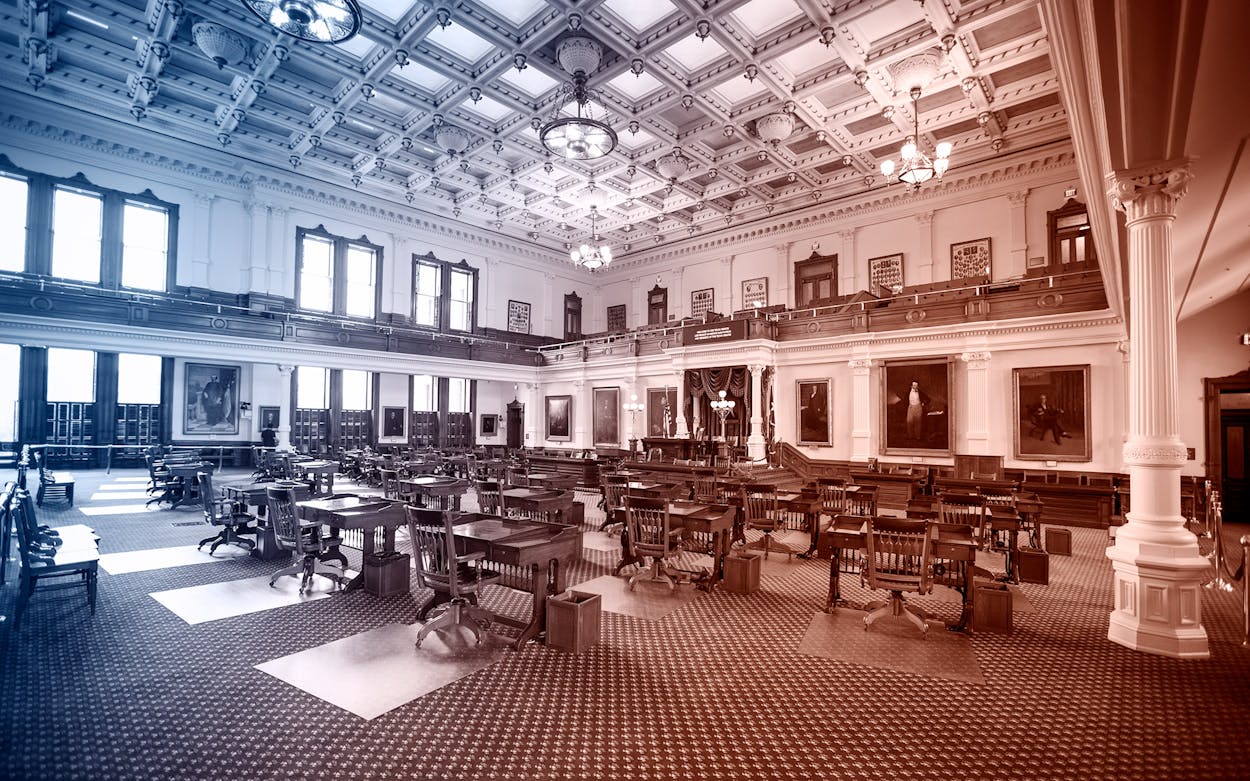

Yet legislation is rarely discussed in terms of raw interests. Almost nobody says “I want more power” or “I value this person more than that person.” Wednesday’s hearing of the House State Affairs Committee, which considered four bills that would preempt local ordinances regulating how employers treat employees, provided a lesson in what legislators do instead: They rationalize.

State representative Dade Phelan, the Beaumont Republican who chairs the committee, introduced the four: Senate Bill 2485, which would nullify ordinances that mandate certain employee benefits like health insurance and retirement plans; SB 2486, striking down ordinances that mandate scheduling and overtime protections; SB 2487, overturning mandatory sick leave; and SB 2488, preempting ordinances that prevent employers from asking about criminal history on initial job applications, a.k.a. “ban the box.”

It was an unusually rowdy hearing. Scores of businesspeople turned out to support the bills, and a few businesspeople came to oppose them, including a restaurateur who had helped Austin draft the ordinance. Responding to the argument that Austin’s ordinance would scare businesses away, Brandon Campbell told the committee, “If we could make laws to stop people from coming to Austin, it would be a miracle.” Be careful what you wish for, said Phelan. “Let’s give it a try,” said Campbell, to which other Austinites cheered.

The ordinances really do come at a cost, and many small business owners claim that the rules are poorly drafted or pose specific problems for their industries — construction, hotels, hospitality. The question is, are those burdens worth it for what they provide in return? Rather than speak in those terms, though, Phelan told his fellow legislators that the question of the bills “just comes down to your philosophy of whether or not municipalities should be doing this or your state should be doing this.”

The question at hand might be less than philosophical in nature. The idea of “local control,” the principle that “the government closest to the people serves the people best,” as Thomas Jefferson put it, has become something of a running joke at the Legislature. Local control was once held to be important, if situationally so, until the state’s big cities started electing Democrats, at which point municipal self-governance became not very important at all.

Phelan and others warned that the ordinances created a patchwork of laws across Texas, though this is of course an argument that could be appropriated by advocates for a more powerful Congress. Phelan also argued that the ordinances would force businesses to pass costs on to customers, raising the cost of living. This was a strange thing to hear in the middle of a session where the heavy hitters are trying to raise the sales tax, in effect passing the cost of government to the consumer. Even apart from that, it seems hard to make the case that lawmakers have any real interest in the relative cost of a beef fajita plate in Dallas versus Irving.

Phelan offered advice to local governments, telling them that “you have to understand how Texas works, how our climate works, how we’ve become a very pro-business state.” His invocation of the state’s “climate” brought to mind Arthur Jensen’s booming monologue in defense of business at the climax of Network: “You have meddled with the primal forces of nature — and You! Will! Atone!”

The effort to wipe away local ordinances stumbled for a moment when language was included in another Senate bill that would also have threatened cities’ non-discrimination ordinances, which protect transgender and other people from discriminatory hiring practices. This presented a problem. If the principle at stake is that only the state should regulate economic activity, the NDOs clearly should go. But business groups took the position that erasing the NDOs would in fact cost the state money, because it would make certain businesses less likely to move here.

So philosophy bent to practicality, and Phelan voted out of committee a version of SB 2486 that explicitly protects NDOs, which means that the committee approved a bill that specifically enshrines cities’ right to regulate part of the the employer-employee relationship inside a bill passed with the argument that cities should have no right to do so.

To Republican state representative Phil King, the very idea of the ordinances was an affront. “I don’t understand how anyone can make decisions for someone else when they have such little information to go by and paint with such a broad brush,” he said. “I don’t think it’s democracy. I think it’s dictatorial.” (To be clear, King is a member of the Texas Legislature, a body that has never seen a brush too wide to wield, and that passes laws with sweeping repercussions for a state of 29 million people in a span of a few months in spring every other year.)

In truth, the Legislature is its own kind of business. It derives its tremendous power from being the state’s ultimate regulator and de-regulator, the body that writes the laws that constrains economic activity. Without it, semi-oligopolies such as car dealerships and wholesale beer distributors might not exist at all, and in return those industries and others pump millions and millions of dollars into the political system. Lawmakers and the lobby depend on one another, and when Congress above them or cities below them claim that regulatory power, it makes that relationship weaker. Lawmakers have a personal, vested interest in reclaiming that power for themselves. It might be as simple as that.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Business

- Phil King