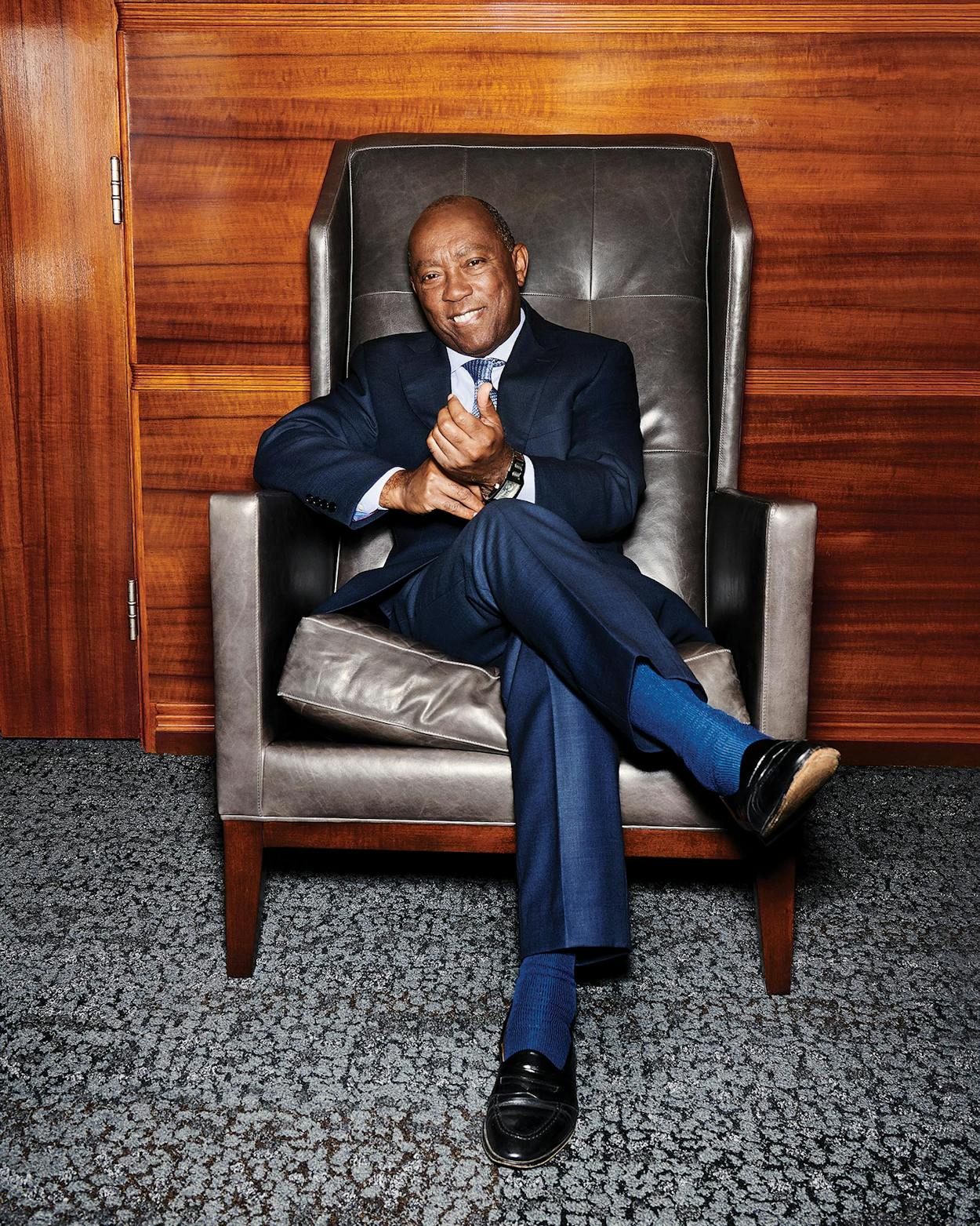

At the end of a long day, Houston mayor Sylvester Turner has the look of a man who is gamely trying to get through his last appointment without displaying the desperation he feels for a little peace and quiet. He’s running behind. People have been ushered in and out of his sprawling, light-filled city hall office for the past couple of hours, while the sun sinks lower and lower on another ruthlessly hot October day. There should be a path worn into the carpet at this point, as Turner walks people in and out, out and in, giving everyone the impression that he has all the time in the world.

His voice is just a little sandpapery behind the poetic cadences that have made him famous for his oratory. There are shadows under his eyes, too. But within a few seconds of greeting, Turner rights himself, switching on a smile that, if practiced, is still welcoming. “It’s been a while,” he says, a line that suggests he remembers the last time you met, even if you aren’t sure when or where that was.

It’s to Turner’s credit that he doesn’t show much wear and tear—he looks much the same as he did when he was elected the mayor of America’s fourth-largest city. Winning that job was a lifelong goal, and he overcame some bruising fights—and eked out a razor-thin margin in the runoff election—to get here. And now, almost three years into his tenure, it’s possible to wonder whether he, or anyone else, could have imagined the challenges he’d face: a seemingly never-ending pension crisis that still threatens Houston’s future. Donald Trump’s attempt, in June, to force the famously diverse and welcoming city to roll up its welcome mat and warehouse the children of undocumented immigrants. And the onslaught of Hurricane Harvey, which devastated large swaths of the city and has forced him to fight the governor and the federal government for billions in recovery funds.

Turner can be criticized—and he has been—for not always having an A-team, for his hotheadedness, and for a certain paranoia toward the local press in particular (he was the victim of a vicious smear campaign back in the nineties, when he first ran for mayor). But through a combination of friendly persuasion and, when needed, a harsh temper, he has held a complex, extremely diverse city together in some of the worst possible times. “Turner is one of the best politicians around,” says Bill Miller, who is probably Texas’s premier political fixer. “He makes a concerted effort to work with everyone, and he makes a concerted effort to understand why they take the positions they do. He doesn’t hang on to things. He’s friendly with anyone who approaches him. He’s straightforward, and he’s honest, and he will work with you. That’s a dream come true in my book.”

And a rarity, especially in a country and state riven by partisan conflict. To be a mayor of a large city these days is to find oneself trying to do more than is possible with ever-shrinking resources and ever-more-vocal groups demanding their piece of the pie. And Houston, despite its claims to openness and tolerance, has long been dominated by wealthy white men—real estate developers, energy company CEOs, managing partners of corporate law firms. Turner is the city’s second black mayor, but he’s the first who isn’t completely beholden to the established power structure. On even the best day, his job requires him to work a Rubik’s Cube that can’t be solved.

So he has his strategies for getting done what he can get done. “I think it is always important to stay focused on those things that are most important,” he says. “Not necessarily what’s important to you, okay? To recognize what’s important to other people. If you are seeking to be a public servant, then you’ve got to put other people’s interests and their needs and their concerns first.”

He makes that belief apparent even in small gestures. Turner doesn’t talk to people from the other side of the yawning chasm between his massive desk and a couple of chairs placed just a little too far away from it. Instead, dressed at this late hour of the day in shirtsleeves, he slides into a swivel chair at a glass-covered conference table and welcomes his guest to do the same. At this close proximity, Turner makes direct eye contact, which he barely breaks over the course of an hour-long conversation. He is nothing if not intense; at 5’8” (“in shoes,” says his spokesperson), he may be slight of stature, but he’s forceful in manner.

The lessons of power, he says, started when he was just a boy in Acres Homes, a black north Houston neighborhood that was poor but, like many in the age of segregation, cohesive. Turner’s father died when he was just thirteen; it fell to his mother—remembered as a strict disciplinarian, with the exacting standards of an old-line European maestro—to hold her family of nine children together on a maid’s salary.

“You know, I grew up having the support of others to help me to get where I am today,” Turner says. “My mom had to get resources from wherever she could for the benefit of her children, and that was no easy task. Being able to talk with other people was important; maintaining good relationships was important.” Talking about his mother, a flash of light comes into Turner’s eyes, and he smiles brightly, as if animated by some memory. “I lived in a house with a masterful politician. She was in charge of her household. She did not have an education, and she was not a high school graduate, but she was masterful at getting what she needed for her kids. I watched her, and so many of the lessons I’ve learned, I learned from her. Relationships are important. Having a word one-on-one is important. Having a strong work ethic is important. I’ve fallen back on all of that as I’ve entered the public domain.” As a child, Turner was so spiffily dressed and studious that the neighborhood kids took him to task for it, but you have to imagine that giving in to peer pressure would have set him on a harrowing course at home.

That upbringing gave him a sense of his own strength, discipline, and authenticity, traits that got him to Harvard Law School, and a fearlessness that must have seen him through more than a few encounters with East Coast elites who had grown up using “summer” as a verb. During his time in Cambridge, Turner drew on a phrase from the Bible that his mother had stressed: “God is no respecter of persons,” meaning that God shows no favoritism. “It doesn’t matter if you are Jew or Gentile,” Turner clarifies. “Doesn’t matter if you are rich or poor. You deal with people as they are. Nobody is higher than anybody else; nobody is lower than anybody else.”

Turner says that when he showed up for law school, he didn’t know he was supposed to be intimidated. “I went to Harvard without even visiting the campus,” he says. “My mom loaded everything I had in a footlocker and gave me a one-way ticket.”

Having grown up in a segregated city, Turner had a finely honed sense of the small inequities that can make a big difference. “At Harvard, I initially took my lunch to school, but I noticed that the other kids were going out to lunch,” he says, launching into a story he’s been polishing for a possible memoir. “That wasn’t working for me, so I went and visited Ms. Ruiz, in Harvard’s financial aid office. I said, ‘Ms. Ruiz, I can’t afford to go to lunch.’ And Ms. Ruiz told me, ‘Sylvester, being up here is not just what you learn in the classroom—a part of the experience here at Harvard is the relationship with other students. So I understand what you’re saying. Let me see what I can do.’ And the next day, I checked my account, and she had put in a significant amount of money. And for me it changed things, because it established more of a level field. Some thirty-plus years later, I’m still interacting with many of the students I interacted with back then. Those relationships are still ongoing.”

“I went to Harvard without even visiting the campus. My mom loaded everything I had in a footlocker and gave me a one-way ticket.”

Over time—at law school, during his years as an attorney at Fulbright & Jaworski, and after he and a colleague started their own firm—he learned the give-and-take of power dynamics: that victory at all costs is never really a victory; that it’s important to listen carefully, to see arguments from all sides in order to find the space for compromise with one’s opponents. The favor bank that was the Texas Legislature, where he spent 27 years in the House of Representatives, was another excellent training ground. In fact, one reason Turner won the mayor’s race was because many believed he was the only candidate with the ability to reach across the aisle in Austin and find a way out of Houston’s decades-old pension crisis, which was created when state legislators agreed to insanely high pensions for city employees, setting the city on the road to financial annihilation. Where his predecessors had failed, Turner coaxed, cajoled, horse-traded, and called in many favors to get his former colleagues—Republicans and Democrats—to reduce the workers’ benefits, reorganize Houston’s debt schedule, and issue $1 billion in bonds. (The firefighters are still fighting Turner as of this month, alas.)

But even Turner admits that times have changed. “When I came up through the Legislature, fostering relationships was critically important,” he says. “Critical. Things weren’t so polarized. Now things are toxic. It makes it very difficult for people to come to know each other. The people that I am able to reach out to now are the people I was able to establish those relationships with before.” Which is likely why even die-hard Republicans like Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick take his calls and, on occasion, help him out. Senator Joan Huffman, a paragon of right-wing virtue, carried Turner’s pension bill in the Legislature.

“My advice is that sometimes you have to refrain from going tit for tat,” Turner says. “Which is hard, which is hard. Stay focused, stay focused, and sometimes you just have to resist adding fuel to the fire.”

Then again, the other motto Turner lives by comes from Frederick Douglass, who famously noted, “Power concedes nothing without demand. It never did, it never has.” Turner feels deeply that he represents everyone in the city, but he is aware that black and brown people have long been underserved—the latest catchword for “ignored”—a fact that was laid bare once again in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey. Turner didn’t hesitate to open the George R. Brown Convention Center to flood victims before there was an official shelter system in place, which allowed more than 10,000 people to find temporary refuge in a desperate moment.

Turner’s efforts to help people literally get roofs over their heads in the sixteen months since the storm have been stymied by Austin’s and Washington’s foot-dragging. But he’s played a pretty good game when it comes to getting federal disaster relief sent directly to his city—in the past, such monies first went to the statehouse before being distributed here, resulting in years of delays.

But Turner’s most striking exercise of power came last June, when the Trump administration started separating families of asylum seekers at the border of Texas and Mexico. When it became apparent that a private company intended to house babies and toddlers in a Houston building, Turner called a press conference. Surrounded by other city officials and religious leaders, along with Democratic legislators, Turner categorically refused to allow the city to become “an enabler in this process.”

The mayor never raised his voice, but he made his intentions clear. “I’ve done my best to try to avoid the politics of ruffling people’s feathers in order for us to move forward in this city, collectively, and to meet our needs, but this issue is different, because this involves our children. This one is different. And there comes a time when Americans, when Houstonians, when Texans have to say to those higher than ourselves, ‘This is wrong, this is just wrong.’ ” You could argue that Turner had simply encouraged the feds to move the baby jails to more remote locations. But absent any ability to stop Trump, Turner’s refusal to allow his city to play a part in this shameful act was a bracing public stance.

“I represent the people in the city of Houston,” he said. “We often say we are the most diverse city in the country, and if you want to be a welcoming city, if you want to stand up for the people in your city—oftentimes that means standing up for the people who don’t know they have a voice for themselves. If they are scared of us or they feel as though they are not welcome here, then you are not representing them. That issue was not a difficult decision.”

It rarely is, whenever Turner’s past serves as prelude. “If people see that your walk is consistent, even if they don’t agree with you, they respect you,” Turner said, adding one more lesson to his power tutorial. “And that’s what’s important. People don’t have to agree with you, but if they respect you, then you are still in the game, okay?”

This article originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Sylvester Turner

- Houston