Lyndon Johnson was a great original, a man whose energy and personality knew few bounds, the polar opposite both of Richard Nixon’s rootless ambition and Gerald Ford’s Midwestern blandness. Only he had the presidential perspective on his controversial years, but his own memoir, The Vantage Point, sets down everything except the man himself. What was LBJ like? A few of his colleagues, aides, and rivals try to give us some idea. The remarks from Joe Frantz, Robert Allen, and Peter Benchley are from the oral history collection of the LBJ Library. General Westmoreland adapted his anecdote for us from his upcoming book, A Soldier Reports. Bill Moyers, Tom Johnson, Ralph and Opal Yarborough, and Bob and Mary Hardesty gave us their recollections directly; they have never appeared before.

Cleaning His Plate

Not long after my return from Saigon, President Johnson told my wife, Kitsy, that he understood that Quarters 1, the Chief of Staff’s residence at Fort Myer, has a spectacular view of the federal city. When, he asked, was Kitsy going to invite him to a little family dinner? Kitsy could hardly believe the President was serious. In any event, what did he mean by a “little family dinner?” She procrastinated until in another meeting some weeks later, the President repeated the question with obvious determination to have his way.

Kitsy finally concluded that a little family dinner might be construed to mean the President and Mrs. Johnson; their daughter Lynda (Luci was away); and, because of the President’s high regard for Bus Wheeler, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs and Mrs. Wheeler. She invited them for the evening of October 8, 1968.

Delayed by business at the White House, the President was over an hour late, leaving Kitsy with considerable concern over how her dinner would fare. Yet all turned out well. The view from Quarters 1 was much as the President had pictured it, and the dinner proved a success, especially when it came to a dessert that was apparently a presidential favorite: rum pie.

The President, having finished his pie, noted that General Wheeler had eaten only a few bites of his.

“Buzz?” the President whispered, getting the chairman’s attention. He pronounced the nickname “Bus” as if it had to do with a bumblebee, and used a tone of voice that seemed about to introduce some monumental business of state.

“Yes, Mr. President?” General Wheeler responded.

“Are you through with your pie?” the President asked.

“Yes, Mr. President.”

“May I have it?”

“Yes, Mr. President.”

Whereupon the President, under the eaglelike gaze of Mrs. Johnson, ate what remained of General Wheeler’s pie.

General William Westmoreland

Leaving on a Jet

I particularly remember a visit to the LBJ ranch in 1968 when all six Hardestys, one speechwriter-father, one nervous wife-mother, and four enthusiastically impressed children were being given the famous “treatment” by their famous host. The President himself was undecided about his plans for the following day. We were definitely programmed to return to Washington, but the problem was a tentatively scheduled stop on the way in Cincinnati, Ohio, for the President to address the National Governors’ Conference being held there.

Johnson called his unpredictability “keeping my options open,” and on this occasion he used that excuse to probe his friends and aides at dinner for reasons to go or not to go to Ohio. The next morning, my husband and another speechwriter wrote a tentative address to the governors, while yet another aide tried to explain the uncertain situation to some agitated people in charge of scheduling at the Conference.

The Secret Service, seasoned by years of sudden and traumatic Johnson departures, and fortified with the knowledge that when the President boards his airplane, it takes off, told us to pack our bags before breakfast.

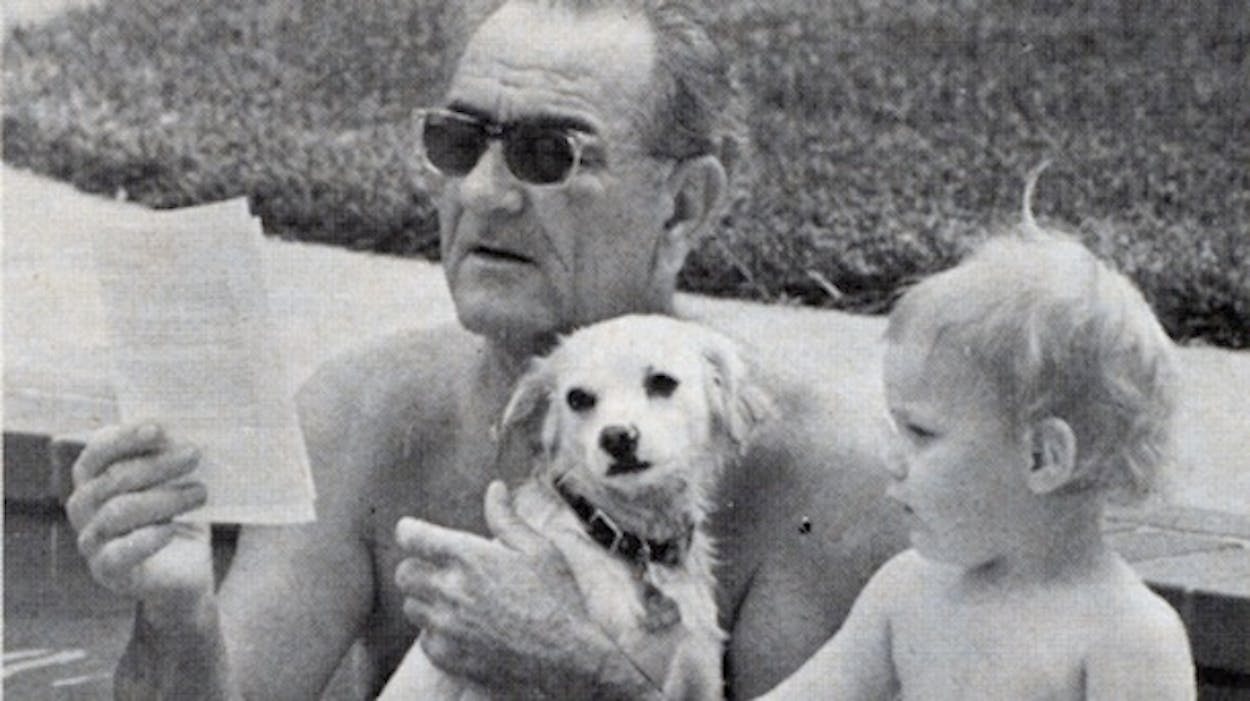

After lunch, most of us were sitting around the swimming pool area in the front yard, relaxed, talking in low voices, suspended in the still, clear Texas summer, waiting for the decision from Above about when we would go.

All at once the door of Johnson’s bedroom, which was situated in a wing of the main ranch house, opened. Down a walk leading from his bedroom door to the pool came the President, wrapped in a bathrobe from which he emerged in trunks, ready for a swim.

Johnson swam around a while—he really paddled more than exercised—going occasionally to the side of the pool where he would converse with one of his aides, or talk on the telephone with someone in Washington about national and international problems, or with equal concentration to someone in nearby Fredericksburg about buying cattle. But not about the trip. To anyone.

The rest of us began to relax, as Johnson was doing in the pool. We, the audience, pretty much realized that since Johnson wasn’t even dressed, there just wasn’t going to be time to leave immediately as would be necessary in order to make dinner in Cincinnati. We began to think about how to spend our last leisurely day in the Texas sun before our return to Washington that evening.

Finally, casually, the President strolled up the steps of the pool, put his robe back on, glanced around, and started off.

Instead of going back up the walkway to his bedroom, Johnson took another path which went across the front of the ranch house. We figured he was going to his ranch office which occupied the wing opposite the bedrooms. After all, he was in his bathing suit and bathrobe, he had to enter the house somewhere to eventually change clothes. If that happened, it might mean we were going to Ohio after all, and, with so little notice, there would be come scrambling to be ready to leave when he was.

But Johnson continued past the front door, past the last side door, rounded the corner of the house, and headed out towards the runway where his small jet sat, the one used to transport him to and from Bergstrom Air Force Base where Air Force One waited ready to jet out on notice.

Like figures in a freeze-tag game, we grew absolutely still as the last glimpse of the disappearing President told us like a revelation that a decision had been made. He was going to Cincinnati in his bathrobe.

He was going to Cincinnati in his bathrobe? A startled Harry Middleton asked a Secret Service agent, “My God, is he going to the Governors’ Conference in his bathrobe?”

The agent replied under his breath, “He’s got clothes on the plane.”

We activated like bombshells. People ran in all directions, to cars which tore around to the guest houses collecting suitcases and stray children, inside gathering up the Johnson travel gear, outside preparing the airplane for take-off. Within ten minutes we were all, Secret Service agents, guests, aides, and families, airborne and breathless, trying to follow Mrs. Johnson’s standing advice: “Just look on it all as one great adventure.”

We were on our way with President Johnson to Ohio, and who knew what might happen there?

Mary Roberts Hardesty

The Treatment

It was my first understanding of the Johnson Treatment. I walked in with Mr. Kintner, and the President was at the time finishing an interview with an Indian. I don’t know what position in the diplomatic corps of India he held—he was a very slight, short man—and as we stood in the door to the President’s small office off the Oval Office, LBJ was exhorting this Indian about Viet Nam and towering above him, waving a hand at him. He gave him that story which he subsequently used—I hadn’t heard it before then—in which he would say with grand gestures that “all he wanted was if Uncle Ho Chi would take off his gun belt and put the hand grenades away, well then, I’ll put down my guns. But if he doesn’t and I put down my guns, you know what, he’s going to shoot me right in the rear end.” This Indian was nodding politely, awed; he was about five-feet-one and looking up at six-feet-four of Lyndon Johnson. He was quite terrified.

Peter Benchley, former LBJ speechwriter and author of Jaws

The Personal Touch

He went to great pains to show that he was deeply involved in the inner decisions of the Administration, that he was the real insider. One day in early 1961 Russell Baker, then a Hill reporter for the New York Times, who knew Johnson well, had been coming out of the Senate when he was literally grabbed by Johnson (“You, I’ve been looking for you”) and pulled into his office. Baker then listened to an hour-and-a-half harangue about Washington, about how busy Lyndon Johnson was, how well things were going. There were these rumors going around that he wasn’t on the inside; well, Jackie had said to him just the other night at dinner as she put her hand on his, “Lyndon, you won’t desert us, will you?” They wanted him. It was pure Johnson, rich and larger than life, made more wonderful by the fact that if Baker did not believe it all, at least for the moment Johnson did. And in the middle of it, after some forty minutes, Baker noticed Johnson scribble something on a piece of paper, then he pushed a buzzer. A secretary came in, took the paper, disappeared and returned a few minutes later, handing the paper back to Johnson. He looked at it and crumpled it. Then the harangue continued for another fifty minutes. Finally, exhausted by this performance, Baker left and on the way he passed a friend named David Barnett, also a journalist. They nodded and went their separate ways, and the next day when Barnett ran into Baker, he asked whether Baker knew what Johnson had written on that slip of paper. No, Baker admitted, he did not know. “ ‘Who is this I’m talking to?’ ” said Barnett.

David Halberstam from The Best and the Brightest

From the Heart

One day in the Oval Office President Johnson was going over possible nominees for a vacated Supreme Court seat. Each of the men on the final list had his champion, and strong arguments were made in favor of several candidates, one of whom was Thurgood Marshall. I was taking notes in the meeting, and it was clear that strong arguments were being made on behalf of one or two other men than for Marshall. After everyone had filed out and I was preparing to leave, the President looked up at me and said, “Tom, I’m going with Thurgood Marshall.” I was surprised and asked him why. “Well, Tom,” he said, “You’re from Georgia. You know what it’s like there. But now those poor downtrodden black children will be able to look and see a black man on the Supreme Court of the United States. And they’ll know, too, that they can make it.” That comment came out of his gut, came out of his heart. He had heard all the presentations with his head, but the decision came from his heart.

Tom Johnson, former LBJ press secretary

Oh, My Achin’ Shins

Hubert Humphrey told me how Johnson gave him pep talks and Humphrey demonstrated, saying, “He’d grab me by the lapels (to demonstrate, Humphrey grabbed me) and say, ‘Now Hubert, I want you to do this and that and get going,’ and with that he would kick me in the shins, hard.” Then Humphrey added, “Look,” pulling up his trouser leg. Sure enough, he had some scars there. He had a couple of scars on his shin where Lyndon had kicked him and said, “Get going now.”

Robert Allen, Washington columnist

Ho Ho Ho

People always said that he did everything for publicity, that he always carried the opinion polls around in his pocket. I don’t want to dispute that, but I do know that many of the best things he did were deliberately without publicity. He had a ranch down in Mexico, for example, and every time he would go down he would take in birth control pills and nutritional supplements for the villagers. He was always after the President of Mexico to open up a school there, to bring in nurses, to improve the place. There was just this tenderness to him, particularly with children. After he had left the presidency he had a whole plane load full of toys flown to the Hill Country from Marx and Company in New York. I’ll never forget that picture of him, the former President of the United States, dressed up as Santa Claus and handing out toys. He didn’t want that to be in the papers, either. He did it because that’s just what he felt. I guess that’s the same reason he went, when he was in poor health and near his own death, to the funeral of some children who had been killed in a bus accident. When I asked him why he had gone, since he didn’t know any of them personally, he said, “Tom, those were the kind of people who cared about me, and I care about them.”

Tom Johnson

Back to the Indians

Lyndon Johnson never liked to give a speech that didn’t contain a news lead. “It’s a waste of my time. It’s a waste of the audience’s time. And it’s a waste of the reporters’ time.”

The problem was, as Budget Director Charlie Schultze used to tell us speechwriters on a regular basis, news leads, especially if they were announcing new government programs, had a tendency to cost money—lots of money. So at Schultze’s request, we used to send him advance copies of the President’s speeches so he could try to head off a news lead he didn’t think the country could afford.

But sometimes, we would be operating on such a tight deadline that the speech would be delivered before Charlie had a chance to review it. And sometimes the President would start ad-libbing in the middle of a speech and do his own violence to the budget.

One day he called Will Sparks and me into the office and told us to start working on a speech he could use in conjunction with a swearing-in ceremony for Robert LaFollette Bennett, whom the President had just appointed Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

It was to be a very high-profile occasion. Bennett, the first full-blooded Indian to assume that post in a hundred years, was to take the oath of office in the East Room of the White House—an honor usually reserved for new Cabinet members. Indian leaders from all over the country were invited.

“I want to give Bennett a real send-off,” the President told us. “I want everyone in town to know that he has the full blessing and power of the President behind him. We’re going to do something for Indians, not just talk about it. Hell, even my hero Andy Jackson broke every damned treaty he ever made with the Indians.

“Well, we’re going to reverse that,” he said. “We’re going to give the Indians first-class citizenship. Now I want you two to go back to your office and write me a speech worthy of the occasion. Put some compassion into it. Come up with some programs that will help those people out. Call around the government. Tap some brains.”

Three drafts later took us to the morning of the swearing-in ceremony. It still wasn’t exactly what the President wanted, but he had to go with it.

He started off the speech following the text, talking about Robert LaFollette Bennett bearing an illustrious name and about his being “the right man at the right time for the right job.” The Indian leaders responded warmly. Then the President began recounting the ills we had vested on our Indian citizens, having ignored Thomas Jefferson’s plea to treat them “with the commiseration that history requires.”

The Indian leaders were getting with it now, nodding to each other and applauding. This was all LBJ needed to start winging it. And the more he winged it, the more enthusiastic his audience became. It was like a perpetual motion machine. His fervor sparked their enthusiasm—and their enthusiasm redoubled his fervor.

Still ad-libbing and pacing back and forth, hitting his fist in the palm of his hand for emphasis, he told them why he was swearing Bennett in at the White House: “… to let the country know some of these facts. Because if the President won’t tell the country … we can’t do anything about this 90 per cent substandard housing and about incomes of under $2,000 a year.”

He turned to Bennett and gave him his mandate: Go back to your office “and begin work today on the most comprehensive program for the advancement of the Indians that the Government of the United States has ever considered. And I want it to be sound, realistic, progressive, adventuresome, and farsighted.”

He talked about the need for better housing, better schools, better health programs, and better job opportunities.

The audience was going wild.

He admonished the Cabinet officers and Congressional leaders present to give the new Commissioner the support he needed, “so we can remove the blush of shame that comes to our cheeks when we look at what we have done to the first Americans in this country.”

Turning back to Bennett, he ordered him to go over to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and “clean out the cobwebs”—set up some Civil Service Boards, fire people, if necessary.

And then, to the immense delight of the Indian leaders, he told Bennett that if he ran into any resistance, to go over to the Smithsonian Institute and get a tomahawk.

I was standing at the rear of the room. While the audience was cheering and stomping and whistling, Jim Duesenberry of the Council of Economic Advisers rushed over to my side and said, “Holy God! Someone run over to the Budget Bureau and get Charlie Schultze. He’s giving the country back to the Indians.”

I’ve since thought what a great news lead that remark would have made. Lyndon Johnson would have been proud of it.

Bob Hardesty, former LBJ speechwriter

The Cure for Baldness

George Christian, then LBJ’s press secretary, was in the White House one morning talking with LBJ while the president was in the bathroom. Through the mirror above him the President noticed a thinning spot on Christian’s head. “George, you’re getting bald,” he said. Christian agreed. “It’s because you don’t comb your hair right. Sit down here and let me show you how to comb it.” And with that the President took out comb and brush and for some minutes thereafter very carefully brushed and combed Christian’s hair so that it would cover the bald spot. The President seemed quite satisfied with his results and told Christian that this was the way he ought to wear his hair every day. Christian felt that the President’s style for Christian—which meant combing it pretty much straight forward—made him look like a freak, and as soon as he was out of LBJ’s view he went back to combing it the regular way, which exposed his bald spot.

Dr. Joe Frantz, UT Oral History Project

The Tables Turn

Six months after the1964 election the honeymoon was over and the President began to be roundly criticized in the press. Arriving in his bedroom early on those mornings I would find him fuming and snorting at a story or column lambasting him. When his mood was especially dark I would try to console him: “You have to take the long view, Mr. President. Don’t take it personally. A century from now no one will remember that piece.” He would only glower. One morning my own honeymoon with the press ended abruptly with a sharp—and, of course, unfair—attack from a columnist. When I entered the President’s bedroom, I was almost apoplectic with indignation. He was propped up in bed, reading the story. Looking at me over his glasses, he roared with glee: “Now don’t take this personally, Moyers. Remember the long view. A hundred years from now no one will remember…” On photographs he later inscribed to me, LBJ wrote: “To Bill, who forgot his own counsel when it was his ox…”

Bill Moyers

A Texas Evening

On a crisp Sunday morning in Washington in 1966, our “unlisted” residence phone rang, and a voice said, “The White House is calling …” Mrs. Johnson’s voice came on the wire, and she said to Opal: “Ann and Ed Clark are coming in this afternoon for a visit before their return to Australia (he was the U.S. Ambassador to Australia, appointed by President Johnson), and are to be our guests in the White House for several days. We thought it would be fun for a few of their and our Texas friends to come to the White House for dinner tonight—very informal.”

Ed Clark had been the most successful American Ambassador to Australia in history, and President Johnson wanted to show his appreciation. The Jake Pickles and the Jack Brooks were there. We spent the evening in the family quarters upstairs, and the dinner was served there in the family dining room. After dinner we gathered in the lovely round sitting room—from which there is a breathtaking view of the monuments, Washington, Lincoln, and Jefferson.

The night was crisp, cold, and bathed in moonlight. To enjoy the magnificent view more, we stepped out on the Truman balcony. The President began to yodel to his dogs in the kennels below, to the south of the White House grounds; the dogs answered with full cry, bugling and baying. The President yodeled louder; the dogs bugled and bayed louder, worthy of a Texas coon, wildcat, or fox hunt. The President chuckled and said, “I wonder what those Georgetowners think is going on at the White House tonight.” Indeed the noise was so loud and the night so still that the Georgetowners might have heard the duet loud and clear! Someone in the group said, “Oh, Mr. President, those first families of Virginia who reside in Georgetown must like it, for they think you have transported a Virginia fox hunt (which is so dear to their hearts) to the White House grounds. No doubt they wish they were here with you.”

It was a Texas night at the White House.

Ralph and Opal Yarborough

- More About:

- Texas History

- Politics & Policy

- Obituaries

- LBJ