More than 4.5 million customers in Texas were without power during the peak of outages in the state this week, as freezing temperatures hit parts of the country. This map shows activity at 10 a.m. on February 16, 2021.

Source: poweroutage.us

In November, when the officials who run Texas’s main electric grid took stock of whether the system could handle the coming winter, they felt confident. There would, even under “extreme conditions,” be plenty of power. But last week, an arctic blast mocked their assessment, freezing in about 40 percent of the grid’s power-generation capacity and throwing much of the state into the cold and dark. How could the state’s energy managers have gotten things so wrong?

The fiasco has intensified a long-running fight between fans of renewable energy and backers of fossil fuels, with critics of wind power, which generates 23 percent of Texas’s electricity, blaming the intermittent energy source for the grid’s unreliability. But those attacks are little more than a distraction from two more fundamental problems the polar vortex laid bare. Texans’ thirst for cheap energy—aided by the energy industry’s hunger for profits—left the state’s power sector ill-prepared to weather a winter storm that other states, including neighboring Oklahoma and New Mexico, have weathered far better than Texas has. And the backward-looking regimen that state energy officials use to forecast the weather—a methodology that minimizes the effect of such intensifying factors as climate change, which scientists say can make winter storms more brutal—may have led them to underestimate the approaching storm’s fury.

A wide cast of characters throughout Texas’s lightly regulated power sector appear to have failed to heed experts’ long-standing warnings, notably in the wake of a similar series of outages almost exactly a decade ago. In February 2011, an ice storm struck the state, crippling power plants and forcing rolling blackouts. After that disaster, lawmakers and regulators studied how the state’s electric and natural-gas infrastructure needed to be shored up, as in other states, to withstand punishingly deep and extended winter freezes. Key recommendations from various experts were to require winterizing of power-generating equipment and fuel-delivery infrastructure such as gas pipelines, and to provide for reserve generating capacity that would be needed when demand surged or when some providers went offline. Both moves would impose somewhat higher costs and result in marginally higher electric rates. But they might have averted the much higher costs Texans now face for business disruption, broken pipes, flooding, and spiking electric bills—not to mention human suffering and death.

In the end, those with a hand in the system did very little to improve its cold-weather resilience. With the worst now over—officials announced Friday morning that the power emergency officially had ended, though electric service still was in the process of being restored—a blame game has broken out among those players: the Legislature; the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, or ERCOT, the industry nonprofit that operates the grid that supplies power to 90 percent of the state; the Texas Public Utilities Commission, whose three governor-appointed commissioners oversee ERCOT; the governor; and power producers.

Essentially everything about Texas’s energy system over the past several days failed miserably.

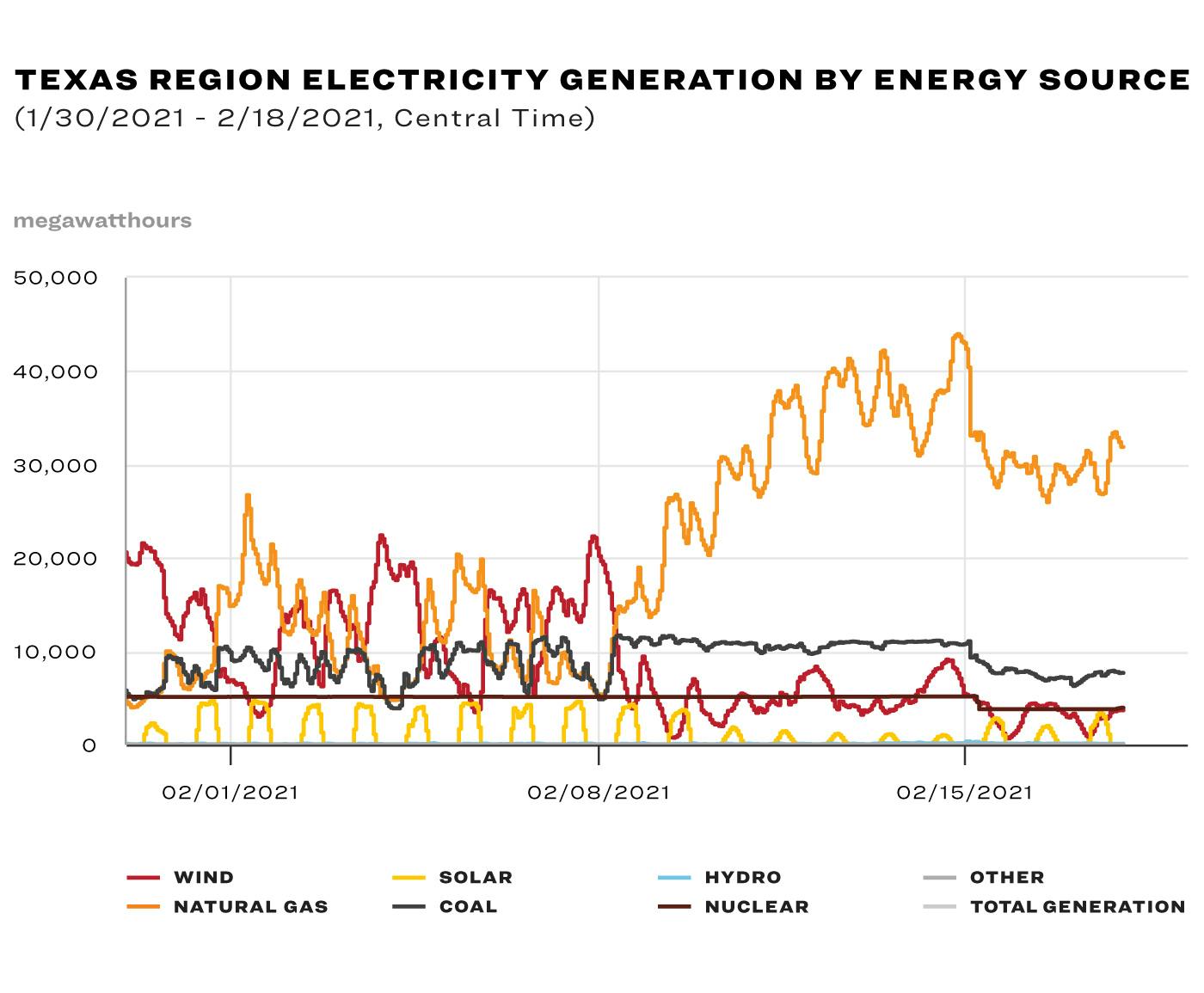

About half the state’s wind turbines froze and shut down—though ones that were winterized have kept going in other states and in regions such as Siberia. But fossil fuel plants, natural gas–fired ones in particular, were a bigger problem, because of a failure to insulate pipes and to otherwise winterize equipment. As of Wednesday morning, when the power outages were at their most severe, the cold had snuffed out about 46 gigawatts, or about 40 percent, of power-generation capacity in the state. (A megawatt is enough capacity to power about two hundred Texas homes.) Sixty-one percent of the loss was from what ERCOT calls “thermal” generation, a category consisting mostly of gas, coal, and nuclear, and 39 percent was from wind and solar. By Friday morning, things had considerably improved: the amount of power-plant capacity offline had declined to about 34 gigawatts, of which about 59 percent was thermal and 41 percent was wind and solar. Contrary to claims by Governor Greg Abbott and others, roughly half of the state’s wind turbines continued to operate, and without them the crisis would have been worse.

“What we really learned this time is that, in such an extreme event, we saw every kind of generation have trouble,” Bill Magness, ERCOT’s president, told me by phone on Thursday. Weary after a week of fighting to keep his system running, he described the severity of the weather that hit Texas over the past week as “shocking.” But it’s not as if a bad winter storm wasn’t anticipated in advance. In the day preceding the arctic blast, ERCOT forecast extremely cold temperatures and asked Texans to conserve energy so as not to overburden the system.

ERCOT, it’s clear in hindsight, didn’t adequately prepare. As a consequence, the grid, its operators, and power producers were overwhelmed by the intensity of what hit the state—particularly Sunday night, when power plants began cratering. The ERCOT grid, Magness said in a separate call yesterday with reporters, was “seconds and minutes” away from a total blackout—an uncontrolled event that, had it happened, later would have required essentially firing it up from dead. The procedure, known in the industry as a “black start,” never has happened in Texas but is the subject of annual ERCOT drills. It would involve activating diesel generators at designated power plants across the state to restart them, gradually reintroducing electricity into nearby power lines, then linking together these re-powered “islands” until the ERCOT grid is back up, Dan Woodfin, ERCOT’s senior director of system operations, explained Friday. “It’s just an incredibly difficult process and takes time,” he said.

Had such a blackout occurred, it would have brought the state to its knees, potentially for weeks or months, an economy that would rank tenth globally if Texas were a country. The emergency required “immediate action,” Magness said, which is why ERCOT began ordering what it terms the “controlled” blackouts that cut off electricity to much of the state.

Partisans eager to use Texas’s 2021 energy nightmare to impugn either renewables or fossil fuels can cherry-pick from ample evidence, and they’re doing so. On Tuesday, Abbott, taking a dig at a package of proposed federal clean-energy measures, told Fox News’s Sean Hannity that the Texas blackouts prove “how the Green New Deal would be a deadly deal for the United States of America.” Texas’s “wind and solar got shut down,” the Republican governor said, which, he added, “just shows that fossil fuel is necessary.” By contrast, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the New York Democrat and stalwart proponent of the Green New Deal, tweeted later that day that Texas’s winter energy woes “are quite literally what happens when you *don’t* pursue a Green New Deal.” As it happens, the performance of Texas’s wind turbines over the past week wasn’t all bad. Many of them froze over and stopped working, but many of those that continued to spin were producing more power than ERCOT, in its pre-winter projections, had anticipated.

For the record, no one who is well-informed about energy is suggesting that Texas, or, for that matter, the nation or the world, can or should operate without fossil fuels—in at least the next several decades, beyond which predictions are meaningless. The relevant question is how much more an electric grid can rely on variable renewables such as wind and solar without rendering the system so unstable that it becomes prone to crashing. Other places, notably parts of Germany, have achieved levels of wind and solar production that exceed Texas’s, with stable grids. And wind turbines function just fine in chilly Denmark and, for that matter, Minnesota. The question is particularly pressing for Texas given that it has chosen to maintain an electric grid that’s less connected to other grids than is common—a situation that, as this week demonstrated, provides Texas comparatively less backup from its neighbors if something goes wrong.

One reason for the misplaced optimism at the beginning of this winter may be the backward-looking nature of ERCOT’s forecasting method. ERCOT projects weather, Magness explained to me, by taking into account “what we’ve seen” in the past and modeling “what we can see” in the future. It employs meteorologists, who tend to focus on coming weeks and months, but not climate experts, who try to peer deeper into the future. “We take into account what our forecasters believe makes sense,” and “we try to add relevant factors” to the forecasts based on events, Magness said. From now on, one such factor—“a new marker,” as Magness put it—will be this catastrophic storm. But whether the severity of the deep freeze will prompt ERCOT to consider integrating more climate-related factors into its forecasting remains to be seen. “If this leads us to look at anything differently, we’ll discuss that” in the future.

Even leaving aside the state’s comparative lack of rigor in assessing climate risk, it wasn’t as if those running the Texas energy system’s various fiefdoms—the grid, the power plants, the natural gas–production facilities—hadn’t been warned about the dangers of severe weather. Hell may not freeze over, but history suggests that Texas’s energy system does—and with some frequency. In 1989, in 2003, and in 2011, the state experienced, to varying degrees, simultaneous shutdowns of power plants and parts of its natural gas–producing infrastructure, as significant swaths of both of those critical systems were incapacitated by arctic temperatures, triggering blackouts.

The frigid weather during the first four days of February 2011 knocked off enough power generation throughout ERCOT—about 29,000 megawatts of capacity—that ERCOT initiated blackouts affecting about 3.2 million customers, according to a voluminous postmortem of the failure produced in August 2011 by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the North American Electric Reliability Corp. That report suggested the state add teeth to its effort to gird its energy infrastructure for wintry weather. Among its policy recommendations was that in states in the Southwest, including Texas, legislatures require power companies to submit winterization plans and give their public-utility commissions the authority to require senior executives of power companies to sign off on those plans and the authority “to impose penalties for non-compliance.” Magness, the ERCOT chief, said that in the wake of the 2011 report he and others met with Texas power generators to suggest that they better winterize their facilities. He was asking, not telling. “It wasn’t a conversation like, `I’m your regulator and you have to do this,’” he recalled. “It was sharing those best practices.”

Some states have gone further than Texas in acting to protect power infrastructure within their borders. They impose weatherization requirements on electricity generators. And many states’ power-market rules allow electricity generators to be paid to hold power in reserve in case it’s needed. Under the deregulation scheme passed by the Legislature more than two decades ago, Texas has a market design that allows generators to make money only by selling juice—not for investing in equipment that could help produce extra power in the event of an emergency. Critics contend that this approach, part and parcel of Texas’s aversion to regulation, makes the state’s energy system less reliable, even as it boosts profits for some market participants. Based on their biographies on the ERCOT website, at least eleven of the fifteen ERCOT board members have current or prior ties to the energy industry.

When we spoke midday Thursday, Magness told me he thinks Texas lawmakers, as they investigate what went wrong this past week, ought to explore weatherization mandates. He noted, however, that better weatherizing power infrastructure, like inducing electricity producers to invest in extra generating capacity, likely would raise Texans’s electricity rates. “Is it worth the cost to consumers?” he asked. I asked him if ERCOT had any answer to that question. “I am not aware,” he said, “that we have ever conducted a real cost-benefit analysis on that topic.”

What became clear over the past week, of course, is the massive cost of an electricity-grid meltdown itself. After Magness and I spoke, IHS Markit, an energy-analysis firm, announced Thursday afternoon that the electricity blackout and frozen pipes in Texas had significantly curtailed the state’s production of oil and natural gas. IHS estimated that nearly 20 percent of natural-gas production, and perhaps an equal or greater percentage of oil production, in the continental U.S. in the first half of February had been shut in—and that the Permian Basin, the big oil-producing region that sits largely in West Texas, accounted for the biggest share of that production drop.

A couple of hours later, the governor, who earlier in the week had called for top ERCOT leaders to resign, issued an announcement. Years after Texas officials had been advised to do so, Abbott said he would ask the Legislature to mandate the winterization of power plants across the state—and to “ensure the necessary funding” for it.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Energy

- Winter Storm 2021

- Greg Abbott