That’s all, folks!

Ben Rowen, 2:09 a.m.

Thanks for staying with us as we live-blogged tonight. We’ll post full thoughts on our website in the days ahead, but for now we’re going to pack it in. Here’s where things stand: as of 2:09 a.m. it’s safe to add 2020 to the growing list of years when the question “Is Texas going to turn blue?” was answered with a resounding “no.”

- Donald Trump has won Texas. There are still votes to be counted in blue counties, but the president’s six-point lead is safe. That’s not as good as his nine-point lead in 2016, but he significantly outperformed the polls and most expectations.

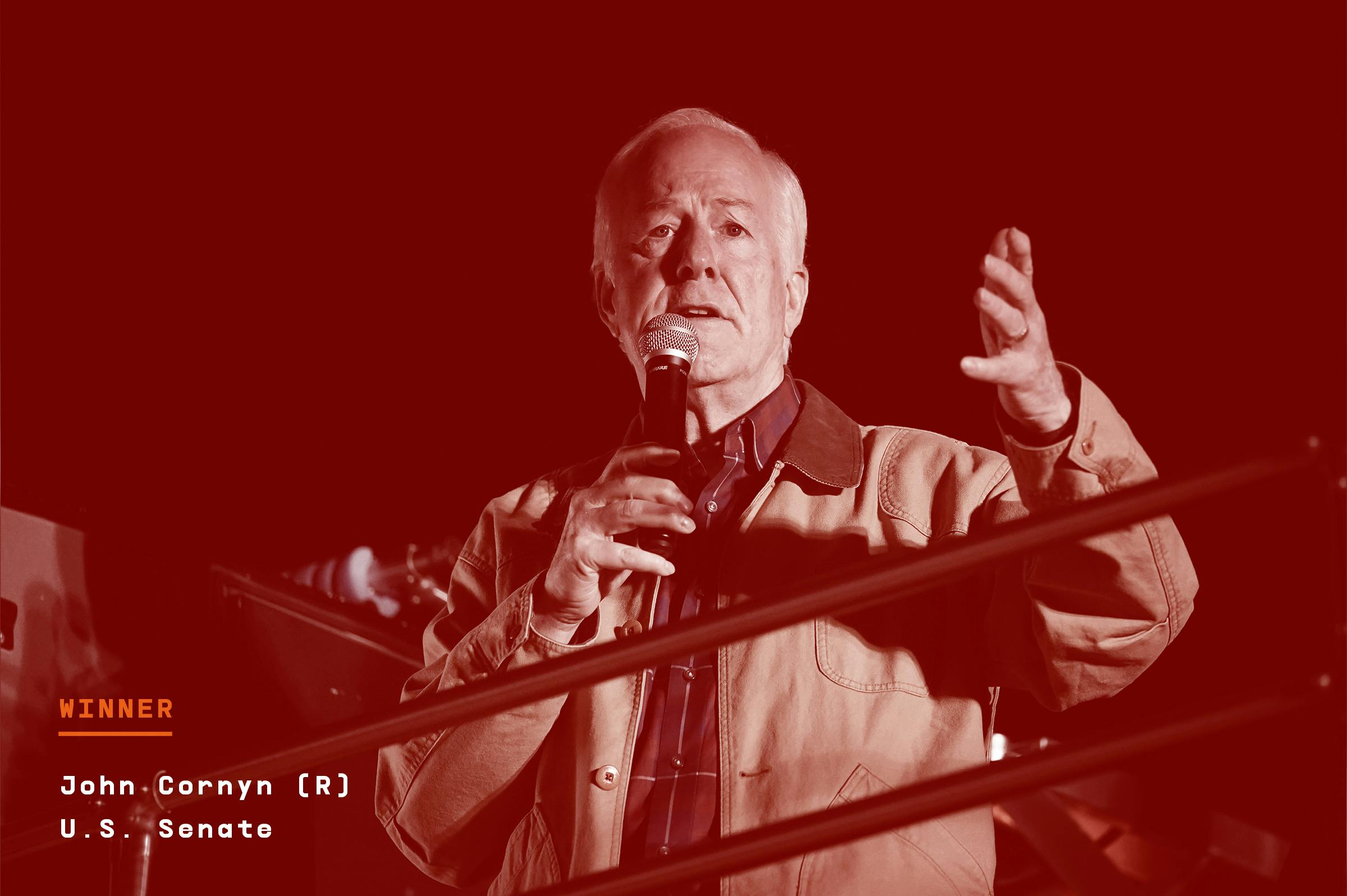

- John Cornyn defeated MJ Hegar in the Senate race by a larger margin than Trump beat Biden by. There was also a substantial Biden/Cornyn crossover vote, as expected. Texas’s senior senator cruises easily into a fourth term.

- As things currently stand, Texas Democrats have picked up zero seats in the U.S. House. A small relief for the party: it didn’t lose any seats either. But Texas Dems expected to win—not just compete—in as many as half a dozen districts currently held by Republicans. Instead, Wendy Davis lost her race against Chip Roy in Austin. Mike Siegel lost to Michael McCaul in a district spanning from Austin to Houston. Sri Kulkarni lost to Troy Nehls in the Houston suburbs of Fort Bend County. In TX-23, Gina Ortiz Jones lost to Tony Gonzales. And not only did Democrats lose, in many cases they lost by larger margins than they had in 2018, the cycle that convinced them the races were winnable in the first place.

- There is just one U.S. House race yet to be called. In TX-24, Candace Valenzuela trails Beth Van Duyne.

- Democrats look unlikely to win the state House. The party needed to pick up nine seats to claim a majority, a total it won’t reach. Democrats could end up with a net gain of zero seats.

- Republicans won every single statewide race, from the U.S. Senate down to the Texas Supreme Court and the Railroad Commission.

Texas showed up en masse, but Democrats went bust

Forrest Wilder, 2:00 a.m.

For many years, forever and ever in political time, theorists and hard-bit Democratic campaign veterans alike repeated a mantra of sorts: Texas isn’t a red state, it’s a nonvoting state. The theory made a lot of intuitive and empirical sense. The state has long put up some of the worst voter turnout rates in the nation, thanks to some combination of an anemic Democratic party, voter suppression, and demographic characteristics that tend to correlate with low civic participation. What if, on some fortuitous day, Texas saw a huge surge in turnout? What if instead of just the same base group of voters—conservative, mostly white—Texas’s diverse electorate showed up en masse to cast ballots for candidates of their choice? Well, tonight was not a perfect experiment by any means, but the turnout percentage will likely end up somewhere in the upper 60s, the highest in nearly three decades.

But the results were not what Democrats were expecting. Votes are still being counted, but it’s safe to say the blue wave ended up being less of a once-a-generation Mavericks, a crashing tsunami that wiped out all those who stood in its way, and more like Port Aransas surf with an onshore gale, a relatively puny thing easily weathered. After all the fuss and fighting, all the oceans of money spent and the wagers made, Texas Republicans remain in firm control of Texas. It is, in so many ways, status quo ante.

The final tally is yet to be made, but it’s certain that Democrats will not have a majority in the Texas House, and they very well may gain no seats at all, a truly astonishing feat given the private and public hopes that they would gain the majority by flipping at least nine seats and perhaps as many as a dozen or more. Just today, Democrats were declaring their candidacies for Speaker of the House. Tomorrow, they’ll be debating which Republican to support for the 2021 legislative session. Republicans will be free yet again to draw new maps to their liking, perhaps locking down another decade of favorable seats.

On the congressional front, things look equally bleak for Democrats. As of 1 a.m., they hadn’t won a single seat, and in the only two races yet to be called—West Texas’s Congressional District 23 and the Dallas-area Congressional District 24—the two Democratic candidates were trailing. CD 23 will be especially painful for Democrats and delicious for Republicans. After moderate Republican Will Hurd retired, this was supposed to be an easy get for Democrat Gina Ortiz Jones, who had lost to Hurd by only a thousand votes in 2018. Here’s a majority Hispanic district that hugs the Texas-Mexico border for eight hundred miles from southwest Texas to near El Paso. How could a Democrat lose?

The early tea leaves show Biden terribly underperformed with Latinos in a number of border counties from Brownsville up to Del Rio. Some of the margins that Trump posted ought to set off enough alarm bells to wake up even the most cotton-eared Democratic strategists in Austin and D.C. And clearly Trump has a hold on Texas that the turnout models and the best prognostications of pundits (myself included) couldn’t account for. Tonight’s results will need to be studied carefully to make full sense of them, and even then there will be uncertainties and head-scratchers. But one thing is for sure, the shibboleth that Texas will turn blue once turnout is high enough must be laid to rest.

A bleak night for Democrats

Christopher Hooks, 1:56 a.m.

If you’re able to set aside the context in which the election took place, tonight’s results are a mixed bag for the Texas Democratic party. This was not a Republican blowout like the 2012 presidential contest, in which Mitt Romney won the state by some 16 points, or the 2010 election, in which Democrats won only 51 seats in the state House, or the 2014 gubernatorial election, which Democrats lost by 21 points. Instead, Donald Trump may end up winning by 5 points or fewer, the closest margin a GOP presidential candidate has won by here since 1996. The balance of the state’s delegation to the U.S. House, and its caucuses in the Texas Legislature, will remain about the same as it was after 2018. Democrats did not wind back the clock to 2014, or 2010. They simply made little progress.

But, in practice, and relative to expectations, tonight was an unmitigated disaster for the Texas Democratic party. This was an opportunity for the party to right itself and brush off some of the dust that has accumulated in the thirty years or so since it began its slow decline from its onetime control of state government. A golden opportunity was missed, and it’s not clear that Democrats will get another one anytime soon.

It’s a body blow to the party. Republicans will once again have unchecked control of the redistricting process, drawing legislative and congressional districts in Texas, as they did in 2011. And this time, they’ll have federal courts packed with Trump nominees to approve the maps they draw. (Texas Democrats can try again in 2030, if they’re lucky.)

Texas Democrats were also already ramping up to build on the gains of this election in 2022, when statewide offices—the seats of governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general—are again up for grabs. Tonight’s results sucked a lot of the urgency—and perhaps, the perception of viability—from Democratic efforts in those races.

In 2016, national Democrats had a terrible night, while Texas Democrats had a great one. This year, national Democrats might just squeak out a win—pending whatever horrors are to come in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin—and Texas Democrats got pummeled.

Trump carries Texas

Christopher Hooks, 12:46 a.m.

Texas and its 38 electoral votes will to go to Donald Trump. By a healthy margin, too! In 2016, Trump took the state by nine points. Right now, with 93 percent of the vote in, the president is beating Biden by six points.

That margin will probably decrease. Some 15 percent of the vote in Harris County (Houston) is still out, and so is 16 percent of the vote in El Paso county, 10 percent of Travis County (Austin), and 11 percent of Dallas County. Most if not all of the remaining vote is ballots cast on Election Day—although in Texas, mail ballots received by the end of the day tomorrow are still counted. It will be a while before we know the final count, but Trump’s margin of victory could fall as low as a couple of points. That would be a shockingly bad result for a Republican president in Texas, but, as state Democrats very well know, close losses don’t mean much.

We’ll have a lot of time to go through the results in the coming days and weeks, but the first question for Democrats to answer is: What the heck happened in the Rio Grande Valley? Biden won the region’s voters, but his total collapse from Hillary Clinton’s 2016 performance with the predominantly Hispanic voters of South Texas meant he needed to run up higher margins in blue counties like Harris—and his margins in those places weren’t impressive enough.

Second time candidates, same results

Ben Rowen, 12:05 a.m.

In 2018, Democrats picked up two unexpected victories in congressional races in the Texas suburbs. It was a handful of close losses, however, that reignited Democrats’ hopes of a blue wave—and in some cases apparently convinced Republican incumbents to retire rather than face reelection. Fresh off moral victories, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee added ten races to its list of targets in 2020. Four candidates who shifted large 2016 losing margins to smaller 2018 losing margins sought election again in 2020. All are currently running behind their 2018 margins. It’s been that kind of night for Democrats.

One race has been called: in TX-22, Troy Nehls has been declared a winner over Democrat Sri Kulkarni, who lost by 5 points in a 2018 bid and is now down 7, with 97 percent of the ballots tabulated. Mike Siegel, the Austin labor lawyer who supports the Green New Deal and Medicare for all, came within 4.3 points of unseating Michael McCaul two years ago. Now he’s down 6 points with 91 percent of the expected vote counted.

TX-23 was supposed to be the easiest Democratic pickup in the state. In 2018 Gina Ortiz Jones lost by fewer than 1,000 votes to Will Hurd, who subsequently retired, but she now finds herself down nearly 15,000 votes and 6 points, with 84 percent of ballots counted. Even a candidate in a stretch race for Democrats is underperforming herself two years ago: Julie Oliver tamped Roger Williams’s long stranglehold over TX-25 down to an 8-point lead in 2018; this year she’s losing by 13 points with 90 percent of the vote in.

A lot of the theory behind the second-time candidates’ second efforts was that there were nonvoters in their districts who’d be brought to the polls in a wave year. Turnout surged across the state. It just seems to have also brought more of the MAGA vote. If things hold, by the end of the night, Texas Democrats will have gained a net of zero seats in Congress.

Asylum seekers watch results anxiously in Matamoros

Cat Cardenas, 11:29 p.m.

As the election results trickle in, Victoria is one of roughly a thousand asylum seekers waiting anxiously in the Matamoros migrant camp, just across the border from Brownsville. As a result of President Trump’s “remain in Mexico” policy, thousands of migrants have been made to wait on the other side of the border while their asylum cases are pending. Victoria, originally from Honduras, has been living in the tent camp for over a year.

It’s a cool night, and many of the camp’s residents have gathered together to sing and pray while they wait for the election to be decided. “We’ve been praying to God that it’s Biden,” Victoria says. “We hope that he’ll be able to get us out of here.” On their phones and radios, migrants have been following the election for months, checking in with their relatives in the U.S. to see if they had more information.

If Trump wins, Victoria and her husband are just one of a dozen families planning on packing up and heading back home. “We know that if Trump wins, we lose all hope of ever getting into the country,” she says. “We’re really anxious right now.”

https://twitter.com/itscaitlinhd/status/1323840449807790080?s=21

An outdoor watch party in Houston

Texas Monthly, 10:54 p.m.

A sour night for Democratic congressional candidates so far

Christopher Hooks, 10:20 p.m.

This has been a pretty unhappy night so far for Texas Democrats down ballot, including congressional and statehouse races. The party had identified ten races as legitimate opportunities to flip Republican seats, and expected to truly compete in a half-dozen or so of them. GOP incumbents such as Van Taylor, Roger Williams, and Dan Crenshaw, who were thought to be in at least a little trouble, are way ahead of their Democratic opponents—by at least ten points.

Other races that polling gurus, including FiveThirtyEight and the Cook Political Report, projected to be close look promising for Republicans at the moment. Wendy Davis is losing to Chip Roy by five in TX-21, with 86 percent of the vote in. In retiring Will Hurd’s soon-to-be-former district, TX-23, second-time candidate Gina Ortiz Jones, who lost by fewer than one thousand votes in 2018, is down six points, with 76 percent of the vote counted. Sri Kulkarni, whose close run in 2018 apparently persuaded longtime representative Pete Olson to retire, is losing to former Fort Bend County sheriff Troy Nehls in TX-22 by four points, with 67 percent of the vote tabulated. Only Candace Valenzuela, running against former Irving mayor Beth Van Duyne in TX-24, looks close—she is down by one with 87 percent of the vote in.

There are two spots of consolation for Democrats. Both of the Democratic party’s gains in 2018, Lizzie Fletcher in Houston and Colin Allred in Dallas, are leading, with the latter already sealing a victory.

On the ground in Travis County

Leif Reigstad, 9:37 p.m.

From the moment polls opened in the Austin area to the minute they closed, Travis County’s online map tracking wait times at polling places stayed solidly green, reflecting wait times between 0 and 21 minutes. Rarely did one of the dots that represented polling places turn red, meaning few Austinites had to wait in line for more than 51 minutes.

“It was a very, very seamless process,” said Spenser Spencer, 30, who voted at the Millennium Youth Entertainment Complex in East Austin at around 5:30 in the evening. “I think all the workers in there did a really good job. A lot of them said they’d been up since like four or five a.m., and they had a lot of good energy and were very supportive. They were just really happy to help out. There were some voters who didn’t speak English, and they had other language speakers readily available. Big shout-out—they did a really good job.”

It was similarly smooth sailing later that evening for 29-year-old Ben Lowry, who voted at the Austin Public Library’s Carver Branch in East Austin. “It was quick and painless, no lines,” Lowry said. “I don’t think it could be any easier, really.”

Both Spencer and Lowry said they felt voting is an important duty, especially in 2020. “[Voting] is a staple that this country is built upon—democracy is obviously important,” Spencer said. “There’s a lot of pressure in recent times, a lot of changes that people want, and being able to vote allows you to do your part to get that change to happen.”

Spencer declined to share who he was voting for in the presidential election, citing concerns about the potential for unrest and general uncertainty around what might happen after Election Day.

Lowry, too, initially didn’t want to say who he picked for president, though he ultimately decided to share his choice. “I voted for Biden,” Lowry said. “I come from a pretty conservative house, which is why I’m hesitant in answering— they’re straight-ticket kind of people.”

Lowry didn’t vote in the 2016 presidential election, because he was out of the country at the time. “This is the second time that I’ve been able to vote [in a presidential election], and I’d like to do it more,” Lowry said. “It’s just more and more important, or it seems that way. Just look at how crazy we are these days. [Voting] is the only thing you can do that’s constructive, so you gotta do it.”

Hegar concedes early

Christopher Hooks, 9:25 p.m.

Democratic Senate candidate MJ Hegar had been trailing in the polls against Senator John Cornyn since claiming the Democratic nomination in July, but her supporters hoped a blue wave of unprecedented size would put her through. Not so, it turns out: Hegar conceded around 8 p.m. With 75 percent of the vote, she’s 6.4 points behind Cornyn.

It is not surprising that Hegar lost, but her defeat points to something happening around the state that is a bit surprising. Democrats are doing much worse in down-ballot races than they had hoped. One of the biggest changes to how Texas elections are conducted this year is the elimination of straight-ticket voting. Some Republicans worried this would mean some Trump fans would vote for Trump and then no one else on the ballot. Instead, it seems that a good number of Texans voted for Biden and then for Republicans down the ballot. That’s a body blow to state Democrats, who could end up with a “symbolic” victory, a narrow loss to Trump in the presidential election here, and no actual prizes—the state House or other statewide offices.

Checking in on the Democrats’ chances to flip the Texas House

Forrest Wilder, 9:12 p.m.

There are lots of votes left to count and plenty of very close races, but right now the blue wave that would’ve swept the Texas Democrats back into a majority in the state House for the first time since 2003 may be cresting a little too low for that to happen. Recall that Democrats needed a net pickup of nine seats. Early returns show Republican incumbents mostly hanging on in the crucial battlegrounds of Tarrant (Fort Worth), Collin (Plano), and Harris (Houston) counties. Right now the only bright spots for Democrats are in two races in Dallas County—where Joanna Cattanach nearly leads Morgan Meyer, 49.4 to 48.6 percent, and Brandy Chambers is ahead of Angie Chen Button, 49.1 to 48.7—and in the affluent HD 134 in Houston, where Ann Johnson has a healthy 53.3 to 46.6 lead over pro-choice Republican Sarah Davis.

There are too many races—and too many numbers—for a full run-down. (Plus, things will change as soon as I finish writing this.) But let’s take a closer look at Tarrant County, the last remaining urban area in the state that still leans Republican. In early votes, Trump and Biden could not be much closer. They are separated by a mere 732 votes in a county of 2.1 million. But go down ballot and Republicans are leading in all five state House races in the county. In House District 96, for example, the outgoing incumbent, Bill Zedler, beat out his Democratic opponent in 2018 50.8 percent to 47.2 percent. So far in early voting, the Republican, David Cook, is leading Democrat Joe Drago 50.9 to 46.6. In other words, despite the state’s impressive turnout, not much has moved. It’s a similar story in some of the other races. Bottom line: Democrats will need to make up a lot of ground in Election Day votes to have a shot at taking the House and begin to move beyond minority party status.

Scenes from Election Day in San Antonio

Texas Monthly, 9:05 p.m.

Josh Huskin talked to some of the 94,000 Election Day voters in San Antonio’s Bexar County about their experiences voting and what it meant to them to cast ballots.

Poor early results in Latino-majority counties for Biden

Cat Cardenas, 8:55 p.m.

By the end of the early voting period this year, 2 million Texas Latinos had cast their votes, surpassing the demographic’s total turnout during the 2016 election. As early results come in from several Latino-majority counties in South Texas, Biden is holding on to a narrow lead. The former vice president is currently up by an 8-point margin in Starr County, home to Rio Grande City, by 20 points in Webb County, home to Laredo, and by 12 points in Cameron, home to Brownsville. There’s one problem: Hillary Clinton won Starr by 60 points in 2016, Webb by 52, and Cameron by 33. One potential bit of good news for Biden: with 88 percent of the expected vote in, the former vice president currently holds a 20-point lead in San Antonio’s Bexar County, the state’s largest Latino-majority county, up from 2016, when Clinton won by 14 points.

For years, organizers and political analysts had predicted that young, first-time Latino voters would turn Texas blue. Since 2016, Texas’s Latino electorate has grown by nearly 17 percent. “If you mobilize them, that’s a winning strategy,” says Lydia Camarillo, president of the Texas-based Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, a nonpartisan voter participation organization.

What might have gone wrong for Biden? In its most recent polling, Equis Labs, a Democratic research firm focused on Latino voters, found that the Latino gender gap in support of Trump is largest in Texas out of seven states polled. Its September survey found that 43 percent of Latinos in Texas supported Trump, while only 22 percent of Latinas did. “A lot of times this gap gets chalked up to machismo, but I think it has more to do with the perception of Trump as a good businessman, someone that Latino men aspire to be like,” Equis Labs founder Stephanie Valencia said. “He’s built this story of working to become rich and successful, and I think that resonates with Latino men who came here to provide for a better life for their families.”

A look at the presidential election

Christopher Hooks, 8:35 p.m.

Some 72 percent of the votes have rolled in for the presidential election in Texas. What can we say so far?

One path to Biden winning Texas is for him to secure a tremendous margin in Harris County, where turnout has been extraordinary. With about 85 percent of the vote in, he does not appear to have done that. Clinton won Harris County by 12.3 points; Biden is winning by 13.4. So far he has netted 180,000 votes from the biggest blue county in Texas. He wanted to get more.

Biden’s margin is better in Dallas County, Travis County, and Bexar County, other big, blue vote centers. With almost all the vote in, he has won Hays County and Williamson County, two suburban counties in greater Austin. That’s an accomplishment.

But he has not, it seems, won Collin County or Denton County, two huge suburban counties in the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex. A consolation is that he is losing Collin County, traditionally a huge source of Republican votes, by only two points.

The really devastating news for Biden is that he appears to be doing extremely poorly in the population centers of the Rio Grande Valley. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won Cameron County, at the southern tip of Texas, by 32 points, netting 30,000 votes. With 72 percent of the vote in, Biden is winning Cameron County by just 12 points, netting just 10,000 votes.

A lot could change, of course. Much of bright blue El Paso’s and the state’s rural votes have yet to come in. At the moment, Biden is up 1.1 points in the count. But it should be remembered that in 2018, Beto O’Rourke led for a considerable period before the final tally rolled in.

Low traffic at polling places in Houston on Election Day

Peter Holley, 8:01 p.m.

The West Gray Multi-Service Center—a popular voting location in Houston—was a hub of activity all day, with dozens of Trump and Biden supporters facing off outside the polling place in an unending clash of bullhorns, flag-waving, and music-blasting (including, prominently, the Village People’s “Y.M.C.A.”). The commotion may have turned some voters away, a few poll watchers admitted, and overall turnout was small.

The low Election Day turnout was experienced across the county. After an early-morning rush, voters began to seem like an endangered species at polling locations. At Texas Southern University this afternoon, a location where long lines garnered national attention during primary races in March, volunteers easily outnumbered voters. At voting locations in the Heights, Montrose, and downtown, lines were nearly nonexistent. This evening, the Harris county clerk reported that at least 200,000 votes were cast in-person. Some experts predicted that as many as twice that number could turn up at the polls today.

The relatively low turnout today may be a function of the unprecedented turnout during the early vote period, when Harris County residents turned out in droves, no matter the time of day, shattering previous voting records. By last Friday, 1,436,526 voters in the state had cast ballots, far exceeding 2016’s total. “Everyone voted last week,” one election worker told me when I asked where all the voters were hiding. “This is actually a good thing!”

Some more statewide races to follow

Christopher Hooks, 6:58 p.m.

The most important statewide race in Texas this cycle is for the U.S. Senate seat currently held by John Cornyn, but it’s not the only one happening. There’s also a race for a seat on the Railroad Commission, which regulates the state’s oil and gas industry, and four seats on the nine-member Texas Supreme Court, all of which are currently held by Republican jurists.

In private, Texas Democrats say polling puts them in contention for the Railroad Commission seat and at least one Supreme Court race. Quite a bit of skepticism is warranted until the results come in, but it might be worth adding them to the list of races you’re keeping track of tonight.

The Railroad Commission race is between Democrat Chrysta Castañeda and Republican Jim Wright. Earlier this year, Wright ran a virtually nonexistent primary campaign and still somehow knocked off Republican incumbent Ryan Sitton. Castañeda has run an unexpectedly strong campaign, powered in part by a last-minute $2.6 million cash infusion by former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Of the four Supreme Court races, the one to watch is probably the one between Chief Justice Nathan L. Hecht and Amy Clark Meachum, currently a Travis County district judge. Again, some skepticism is warranted here. No Democrat has served on the Supreme Court since the late nineties. And even if Castañeda and Meachum became the first statewide Democrats elected in decades, they’d have to contend with Republican majorities in their respective bodies.

A Note on Harris County’s Chris Hollins

Forrest Wilder, 6:39 p.m.

While we’re waiting for results, let’s take a moment to consider the brief but highly impactful tenure of interim Harris County clerk Chris Hollins, who is serving in a kind of caretaker role for this election. He was appointed earlier this year after Harris County clerk Diane Trautman resigned in May, citing coronavirus concerns. A relatively unknown quantity, Hollins has received high marks, from Democrats at least, for expanding voter access while fending off an onslaught of litigation from the Texas GOP and far-right Houston activist Steve Hotze. In July Hollins asked Governor Greg Abbott to add extra days for early voting. Abbott added six days, which is probably the single biggest reason why Texas polls have not been overwhelmed by long lines and Election Day, so far, has gone relatively smoothly.

One of Hollins’s biggest innovations—and most heavily litigated—was setting up drive-through voting sites, where voters could cast ballots from their cars. His office also runs a savvy Twitter account that’s heavy on dank memes. Here’s Hollins at a polling site at Buddy’s, a gay bar. Party in the back, democracy in the front? I can’t think of anything more Houston than voting from your car or casting a ballot at a gay bar.

So many choices!!! VOTE first, then party. #vote @BUDDYSHouston cc: @HarrisVotes pic.twitter.com/I9vNCH1Bc7

— Chris Hollins (@CGHollins) November 3, 2020

Hollins is a vice president for finance for the Texas Democratic Party and his website is “ChrisHollinsForTexas.com. I don’t think we’ve heard the last of him.

Scenes from Election Day in Dallas

Texas Monthly, 6:21 p.m.

More than 57 percent of registered voters in Dallas County voted early. Today, Hakeem Adewumi caught up with a few of the 89,000 Election Day voters around the city and asked them about their experiences voting and what brought them to the polls.

A Texas House preview

Christopher Hooks, 5:39 p.m.

The Fake News Media says there’s a presidential election going on, but only dorks care about that. Those in the know know that the elections that really matter tonight are the ones that determine control of the Texas House, the greatest deliberative body in the world other than the Texas Senate.

If Democrats win control of the lower chamber of the Texas Legislature, it would be a political earthquake, the first actual win the party has scored in decades. The state House is the last thing Democrats lost, in 2002, when they were on their descent trajectory—and control of the Legislature allowed Republicans to gerrymander Texas and lock up the state.

Control of the House in 2021 would give Democrats some influence over redistricting—exactly how much is a complicated question—and it would give the party a platform to advertise their vision for Texas. But more than that, as I wrote recently, it would be a huge psychological boon for Democrats. It would represent the end of one-party rule in Texas and the beginning—or the beginning of the beginning—of “normal,” contested politics. And if Republicans are able to stave off this challenge, it would be an enormous relief to them.

So how should you, dear reader, follow state House races as the night goes on? There’s not an easy way to do it. All 150 seats are on the ballot. Most, of course, are safe GOP or Democratic seats. But because there’s so much uncertainty about the composition of the electorate in Texas this year, there’s a long list of seats that could be in play.

Democrats currently have 67 seats, so they need to pick up 9 to take control. But ideally, they get more than that. A bare majority would empower conservative Democrats and dealmaking Republicans to make deals across the aisle. It would be much better to land 80 or 85 seats rather than 76, which would mean a net gain of 13 to 18 seats. To do so would be tough, but given the state’s incredible turnout and the strange times in which we live, it doesn’t seem impossible. Instead of a comprehensive list, here are a few races to keep an eye on to get a sense of how the night might be going.

Democratic Defense

In addition to knocking off Republican incumbents, Democrats need to defend the gains they made in 2018. These districts are predominantly located in the suburbs of Austin, Houston, and Dallas–Fort Worth. They include:

House District 45, in the Hill Country between Austin and San Antonio, where Erin Zweiner, a young star of the Democratic caucus, is facing Carrie Isaac, the wife of Jason Isaac, a tea partier who held this district from 2010 till 2018.

House District 113, on the eastern edge of Dallas County, where Democrat Rhetta Bowers is facing Republican Will Douglas.

House District 135, in the northwest corner of Harris County, where Democrat Jon Rosenthal is facing Republican Justin Ray.

The Beto 9

There were nine state House districts in 2018 that voted for both a Republican state representative and Beto O’Rourke for Senate. If the Democrats sweep these and lose none of seats they picked up in 2018, they will have a slim majority. These seats include:

House District 138, in Harris County. In 2018 Republican Dwayne Bohac retained this seat by only a few dozen votes. Then he quit. O’Rourke won this district by more than six points, so it seems like a prime pickup opportunity for Democrat Akilah Bacy, who is facing off against Republican Lacey Hull.

House District 67, in Collin County. O’Rourke won this district by 5.5 points. Republican Jeff Leach, once a tea party–aligned Republican, has swung to the middle to try to stave off a challenge from Democrat Lorenzo Sanchez.

House District 121, in Bexar County. Formerly the domain of Republican House Speaker Joe Straus, this leafy San Antonio district voted for O’Rourke by just 0.35 points. Republican Steve Allison is hoping to beat Democrat Celina Montoya and keep the district red.

The Astounding Disappearing Republicans of Dallas County

Dallas County was once ruby red. No longer. Of the fourteen state House districts in Dallas County, Republicans controlled only two after 2018. Now they might be about to lose both. House District 108, held by Republican Morgan Meyer, and House District 112, held by Republican Angie Chen Button, both stand a very good chance of flipping blue. Both districts voted for Beto by wide margins, fifteen and nine points respectively.

The Tea Party’s Last Stand

From 2010 to 2014, a large number of tea party Republicans entered the Legislature. Some have left the Lege. Others have been absorbed into the establishment, or moderated their politics. But a good deal of the remaining few stand a chance of being tossed out of their suburban districts. Look particularly to House District 92 in Tarrant County, home of the retiring and indomitable Jonathan Stickland, who is trying to elect a like-minded successor in GOPer Jeff Cason.

Nearby is House District 94, held by Tony Tinderholt, who once advocated capital punishment for women who had an abortion. Also in Tarrant County is House District 93, held by Matt Krause. Beto won none of these districts, so they’re more of a reach for Democrats. But if they take them, it will change the tenor of the House a great deal.

The Fort Bend Three

Fort Bend is one of the most diverse counties in the country, and its rapid population growth has made it politically competitive. There are three legislative districts held by Republicans here. One should be an easy Democratic pickup. Another is more of a reach. The third is a long shot. Looking at results from the three together could provide some indication of how good of a night Democrats are about to have.

The easiest seat to pick up would be House District 26, formerly held by Republican Rick Miller, who resigned after making comments about Asian Republicans challenging him in his primary. The district voted for O’Rourke by 1.5 points. If Democrats aren’t winning this one, their shot at the majority is in trouble.

The middle district is House District 28, formerly helped by the Republican moderate John Zerwas. His resignation triggered a special election, which was handily won by Republican Gary Gates in a special election runoff, 58 to 42 percent, against Democrat Eliz Markowitz. But O’Rourke came within three points of winning here, and Democrats think they have a decent chance at taking it.

The third is House District 85, which extends to rural Jackson and Wharton counties to the southwest. Incumbent Phil Stephenson won this district by thirteen points in 2018, so he’s probably safe. But if results show it’s running close, Texas Democrats should expect a landslide.

What we’re watching: federal races

Ben Rowen, 4:45 p.m.

Welcome to Texas Monthly’s election night live blog! At long last, the torrent of campaign ads/experimental films will mercifully cease and we will have votes to count and races to call—with, perhaps, some standard delays to make sure all ballots are tallied. Our team, including writers Chris Hooks, Cat Cardenas, and Peter Holley, will be keeping on top of breaking news from the field and analyzing results, guiding you through the turbulence of the night.

You’re likely familiar with the major story lines at this point (if you have been under a rock the last few months, condolences, you emerged a day early). After months of lawsuits and executive orders restricting the ease of access to the polls—most recently concerning “drive-thru” voting and the hot dog/sandwich distinction between a “tent” and a “building”—more Texans have cast ballots in an election than ever before. After months of debate about how to safely conduct an election in a pandemic, well, we’re still debating it. And, of course, after months of Zoom campaign events, maskless rallies, and socially distanced debates, the ancient question reverberates: “Is this the year Texas turns blue?”

Stop us if you’ve heard this before. Democrats predicted the state would flip in 2002, 2008, and 2010. In 2013, President Barack Obama visited Austin to support the launch of Battleground Texas, a political action committee formed by a veteran Obama campaign guru. Texas Republican party chairman Steve Munisteri sent out literature calling the group “masters of the slimy dark arts of campaigning”; then–attorney general Greg Abbott said the group was a greater threat to Austin than Kim Jong-un and his nuclear arsenal. A year later, after the organization had moved to Fort Worth to support Wendy Davis’s run for governor, Democrats suffered historic defeats up and down the ballot. Undergraduates of the dark arts, perhaps.

But that was a long, long time ago, in a world where Donald J. Trump was still merely the star of The Apprentice. So much is different this year. Late October polling shows a dead heat between Biden and Trump in Texas. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee has identified ten U.S. House seats that it thinks voters can flip from red to blue. Many Texas Democrats are confident they’ll win the state House. Turnout is breaking records as we speak. Is this the year things finally change? Here are the key races we’ll be following.

Biden-Trump

The big one. For decades, Democratic presidential candidates campaigning in Texas have prioritized hokey platitudes. At a Harris County rally in 2004, presumptive Democratic nominee John Kerry regaled a town hall with a punchline about George W. Bush: “Houston, we have a problem.” He lost Harris by ten percentage points that November. (Yes, once upon a time, Harris County voted for Republican presidential nominees.) In 2008, at a University of Texas at Austin primary debate, Hillary Clinton dissed Bush, telling an audience, “I think our next president needs to be a lot less hat and a lot more cattle.” She eventually lost the nomination to Obama.

By contrast, the Biden campaign seemed to actively avoid any Texas pandering as recently as the Democratic National Convention in August. The lack of Texan representation in the national party’s event offended state party leaders. In late October, Beto O’Rourke begged Biden to show up in the state. It wasn’t until four days before the election that the top of the ticket finally visited, when Kamala Harris went on the stump in the Rio Grande Valley, Houston, and Fort Worth. If the race ends with a close Trump victory, state Democrats will wonder for years about what might have been had the campaign invested more in Texas.

In an ironic twist, supporters of decades-long party punching bag George Bush are one key to a winning Biden coalition—and he might even count on the votes of a few Bushes themselves (reports surfaced of George contemplating not voting for Trump; nephew George P. has endorsed his party’s standard-bearer). While the venerable theories about how Texas flips blue typically envision the state’s burgeoning Latino vote turning out for Democrats (more on this to come throughout the night), Biden’s path to victory likely runs through once solidly Republican suburban communities that have soured on Trump. In other words, the prospective coalition he wins with might not be a sustainable one for future Democrats, if the suburban drift is driven chiefly by Trump. But that’s a problem for those running in 2022 and 2024.

U.S. Senate

There’s a common story in U.S. Senate races this cycle that goes like this: a moderate Democratic woman in a deep red state puts together a huge war chest and wins the support of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee. She then wins an unusually contentious primary against a less well-funded Black state lawmaker and heads into a general election contest against a longtime GOP senator. Here the tale diverges: if you’re Amy McGrath in Kentucky, the story ends with $88 million raised, and a ten-point deficit in the polls against your Republican opponent. If you’re MJ Hegar in Texas, it ends with $24 million raised and a four to five point deficit.

A Hegar victory is not outside the realm of possibility. But if the polls are right and she loses, expect to hear the question about whether Beto O’Rourke would have beaten the bland John Cornyn had he not run for president. It will join “what if Nelson Cruz had timed his jump better” and “what if the refs hadn’t overturned Dez Bryant’s catch” as all-time Texas hypotheticals.

Another data point to keep an eye on: the gap, if any, between Hegar/Cornyn and Biden/Trump. The polls suggest plenty of Biden/Cornyn voters.

U.S. House

After two red-to-blue upsets in U.S. House races in 2018, and after O’Rourke ran well in the suburbs, Texas Democrats finally had a proof of concept of how to put more congressional seats in play. This cycle, the DCCC has targeted ten seats to flip, and half a dozen or so are expected to be truly competitive. No matter where the Democrats fall on the political spectrum, their Republican opponents, without fail, have labeled them as radical leftists. Socialism, it seems, is a big tent coalition.

Central Texas

There are three tight congressional races anchored in heavily gerrymandered Austin. While the three sprawling districts extend in opposite directions—south toward San Antonio, north nearly to Fort Worth, and east all the way to Houston—the campaigns have all become, in part, referendums on the Capital City. Republicans Michael McCaul of TX-10, Chip Roy of TX-21, and Roger Williams of TX-25 have focused their pitches and ads in opposition to the Austin City Council’s decision to reallocate $150 million from the city’s police department. Their opponents have tried to dissociate themselves from “defunding the police.”

“I’m not running for city council; I’m running for federal congress,” health-care administrator and Democratic candidate in TX-25, Julie Oliver, told me recently. None of the three Democrats support defunding the police either. Still, there are questions of whether voters will find their progressive policies compatible with what have, until perhaps now, been rock-solid Republican districts.

Oliver, like labor lawyer Mike Siegel in TX-10—whom McCaul has called “the most radical liberal running for Congress in the entire country”—supports Medicare for all and the Green New Deal. Wendy Davis, who relocated from Fort Worth following her failed gubernatorial run in 2014 and is the nominee in TX-21, is more moderate but has been targeted by Roy as being too “Hollywood” for the district. She is also, of course, inextricably linked to her 2013 filibuster against an anti-abortion bill. The Cook Political Report rates the McCaul-Siegel and Roy-Davis races as tossups, while finding Williams-Oliver to be a likely hold for the Republican.

Houston

What APD defunding is to Central Texas races, the Green New Deal has been to Houston ones: no Democratic nominee in the area other than Siegel supports the plan, but you won’t hear that from their Republican opponents. There is a likely hold for each party in Harris County, and one true swing race in neighboring Fort Bend.

Freshman GOP congressman Dan Crenshaw, of TX-2, the most successful Saturday Night Live creation of the Trump era, rose to Congress on the coattails of a widely panned joke about his eye patch on the NBC show. Subsequently, he has become the rare Republican in Texas running with Trump and succeeding. In early April, the president’s administration guided Republicans to follow the former Navy SEAL’s lead on coronavirus messaging; in August he was the lone Texas Republican elected official with a speaking role at the party’s convention—though he notably didn’t mention Trump once during his speech delivered on the deck of the Battleship Texas. As the state’s suburbs shift away from Trump, the Cook Political Report nonetheless finds Crenshaw with a solid lead against his opponent, Sima Ladjevardian, an Iranian-American lawyer and big-time Democratic donor.

In neighboring TX-7, Lizzie Fletcher, who won her seat in 2018’s blue wave, is expected to win against challenger Wesley Hunt, the sole Black Republican up for federal election in Texas. Although Fletcher’s vote in December in favor of the impeachment of Trump was expected to hurt her politically, no one seems to remember it anymore. Hunt has hammered Fletcher instead as a Green New Deal radical, despite her op-ed in the Houston Chronicle opposing the plan.

In the rapidly diversifying Houston suburbs of Fort Bend County, former diplomat Sri Kulkarni is representing the Democratic party a second time, challenging Sheriff Troy Nehls for the seat vacated by Pete Olson after 2018’s close Republican victory. Association with Trump might be a kiss of death in the district—Nehls removed pro-Trump language from his website after securing the Republican nomination—but he did accept the president’s endorsement in late October.

Dallas

Three moderate Democrats—all people of color—are looking to capitalize on anti-Trump sentiment in the Dallas suburbs to win their elections. In TX-3, Lulu Seikaly, a labor lawyer, takes on incumbent Van Taylor, who has pitched himself as bipartisan. He might be right: in the state house half a decade ago he united Republicans and Democrats who found him difficult to work with. In TX-24, former school board member Candace Valenzuela challenges Republican Beth Van Duyne, the former mayor of Irving, for a seat vacated by tea party conservative Kenny Marchant. Valenzuela, who experienced homelesssness as a child, has run as a moderate and would be the first Afro-Latina elected to Congress if she wins. Van Duyne, who as mayor proposed a city council resolution opposing the imposition of sharia law in North Texas, has moderated her rhetoric in her bid for federal office. In TX-32, incumbent Democrat Colin Allred faces Genevieve Collins, who works for an education-tech company. Collins received Trump’s endorsement in late October, which might not be as helpful as hoped in the rapidly diversifying district.

Cook rates Democrats Valenzuela and Allred and the Republican Taylor as favorites.

South/West Texas

As Democrats have repeatedly failed to make Texas truly competitive, the Twenty-third Congressional District, spanning the border and stretching from western San Antonio to just outside El Paso, has been the state’s one true swing district. Republican Will Hurd won by fewer than one thousand votes in 2018 and subsequently announced his retirement. Democrat Gina Ortiz Jones, his challenger, is running again, against Tony Gonzales. They are veterans of the Air Force and Navy, respectively. While Hurd made headlines for repeatedly voting against Trump, and likely owed much of his support in the swing district to his moderation, Gonzales has actively aligned with the president, who endorsed him in July during a contentious GOP primary runoff. That might hurt him, and Cook finds the race to lean Democratic.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- John Cornyn

- Joe Biden

- Donald Trump