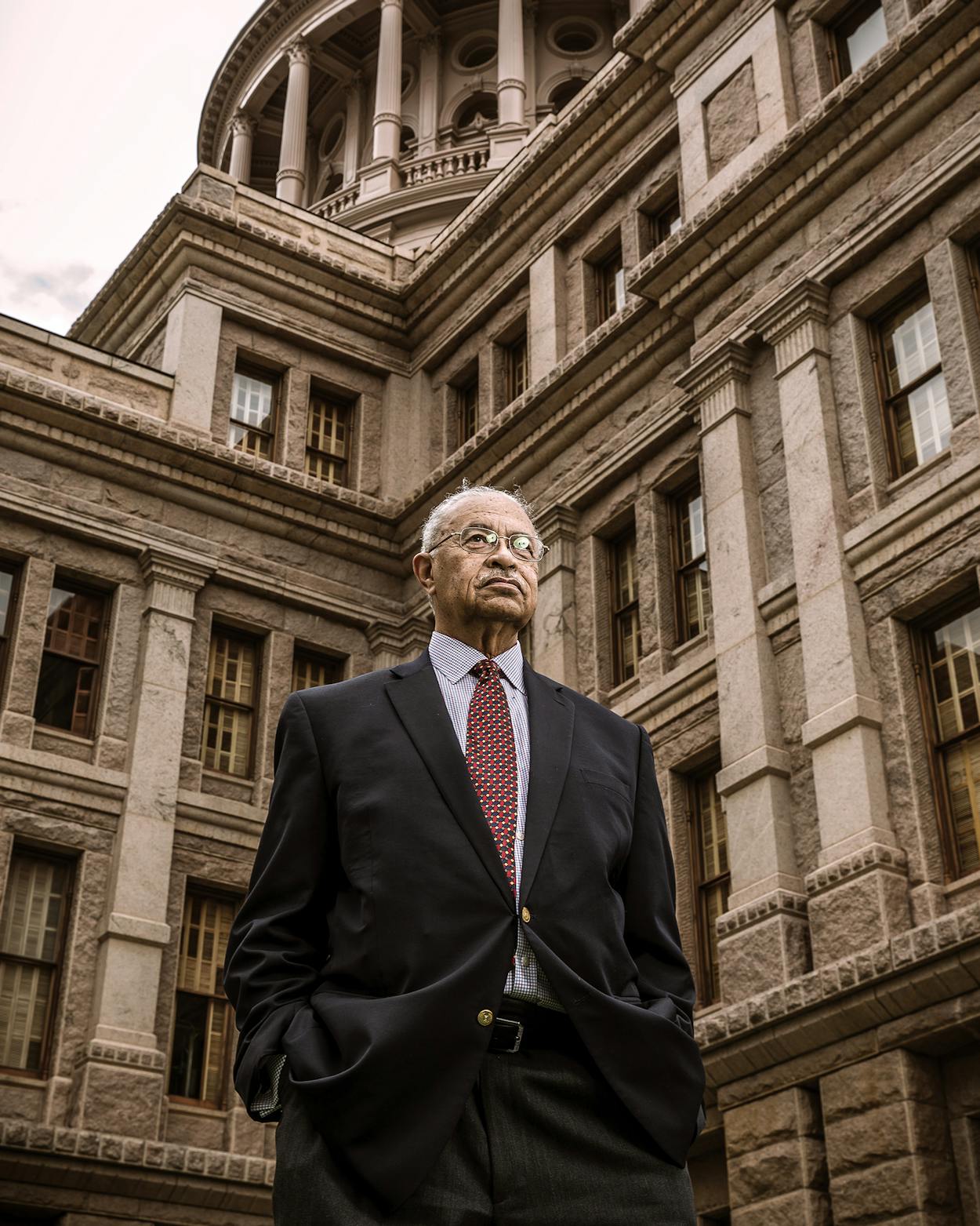

Curtis Graves doesn’t often talk about the past. On most days, he’s deliberating Hillary’s chances or fulminating about the tea party or weighing in on the Confederate flag debate. One of his favorite tangents is the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, the conservative nonprofit that promoted the “stand your ground” bill central to the Trayvon Martin shooting case. “I mentioned ALEC at a dinner party last weekend, and people looked at me like I was crazy,” he said. “They didn’t know what ALEC was, and I thought to myself, What the hell are you reading?” At 76 years old, his six-foot-three-inch frame defies a senior citizen’s stoop, and while his gray hair is thinning, his voice remains the kind of basso profundo that makes even a recitation of his fig syrup recipe sound like a matter of great import.

Though his distinction has faded, he was once an impossible figure to ignore—most notably in 1966, when he announced, as a relatively recent college graduate in Houston, that he was going to run for the Texas House of Representatives. This was brazen. For decades, Texas politicians had consistently deprived black citizens of political power, passing a crippling poll tax in 1902 and adopting a whites-only primary in 1923. Rubbing shoulders with Governor John Connally and Speaker Ben Barnes—or placing a call to President Lyndon B. Johnson—seemed about as likely as becoming an astronaut. But at 27, Graves had already helped integrate Houston’s lunch counters, theaters, and restaurants, and he’d gotten to know local business leaders by managing a bank in the Fifth Ward. With the swagger of Dizzy Gillespie and an indefatigable sense of purpose, he was not to be deterred.

The timing was right: a 1964 lawsuit, resulting in legislative redistricting a year later, had created a multimember district within Harris County that suddenly gave a handful of minorities the opportunity to run for state office. Naturally, Graves wasn’t alone in his aspirations. Lauro Cruz, a gentle but tireless 33-year-old precinct judge, was running for another seat in the House, even though no Hispanic from Harris County had won since 1836, and Barbara Jordan, a whip-smart 30-year-old lawyer who had already run twice for the House before the redistricting—and lost—was now running for the Senate. Of the three, Jordan was the shoo-in, a hometown daughter with a big voice who had been raised in the Good Hope Baptist Church, which not only made up half of Houston’s NAACP membership but was also the city’s center of black political activity.

Graves, a native of New Orleans, did not have such lifelong ties to the Fifth Ward, which meant he had to find other ways to etch his name into the local memory. As the primaries approached, he banded with Cruz to campaign. With the radio dialed to the Motown sounds of KCOH, he and Cruz drove his new, $2,400 black Volkswagen bug down the Fifth Ward’s Lyons Avenue and Lockwood Drive, placing signs on the windows of every barbecue joint, barbershop, and bank they saw. Once, after Cruz had hoisted him over a fence so he could staple a “Graves” campaign sign below a billboard, a Houston police officer pulled over and reprimanded him for posting on private property. “Certainly, officer,” Graves replied. “I was just taking this down.” After the officer drove away, Graves returned to stapling.

He was confident he would win. Though the Voting Rights Act, signed into law by Johnson a year earlier, would not directly affect Texas until a decade later, the city’s African Americans, who had long been politically active, were energized by its passage. It was Houston, after all, that had given rise to Lonnie Smith, the Fifth Ward dentist who challenged the state’s all-white-primary statute and won the case Smith v. Allwright before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944—a landmark ruling that gave blacks a voice for the first time in decades. For years, black newspapers like the Informer had urged their readers to pay their poll taxes and vote. When the city elected its first black school board member, in 1958, a former schoolteacher named Hattie Mae White who was outspoken about desegregation, her name became synonymous with black achievement—a fact acknowledged by her detractors, who promptly burned a cross in her yard.

Graves understood the importance of White’s momentum. Together with Cruz and state representative Bob Eckhardt, a bow-tied liberal eccentric who was running for Congress in the same district, he drove along Navigation Boulevard and through the Fifth Ward each Sunday, staking out black and Hispanic churches at around eight in the morning. After standing at the exits of Catholic churches for a couple of hours to introduce themselves to congregants (Catholics didn’t allow political introductions inside), the three would stop for a breakfast of menudo or huevos rancheros, then hit as many Protestant churches as they could. Speaking to the black congregations, Graves would introduce Cruz and Eckhardt, who’d wave from the pews—often seated alongside Lonnie Smith or Hattie Mae White, who reminded churchgoers of the importance of their choices. “We were beating the drum pretty hard to get the vote out, and you do whatever you have to do,” recalled Graves.

On May 8, the night of the Democratic primary—really the only election that mattered, since he faced no Republican challenger—Graves sat behind a desk at his headquarters on Lyons Avenue, scotch in hand as he received results by phone. Watching his supporters toast one another and eat catered barbecue, he felt the weight of the moment. Just a few years earlier, he’d cast his own first vote, donning a suit and tie for the occasion in New Orleans. He’d endured a literacy test, his voting privilege subject to an elderly white woman’s whims. Now here he was, about to become a Texas state representative—a role no African American had held in the twentieth century. “I remember seeing on the television that Ed Brooke was sure to be elected in November as the first black U.S. senator,” Graves said, “so you knew things were a-moving.”

Just how much things would move for him, however—and how effective he’d be at moving others—was a question that would follow Graves for years to come, a question about the definition of power and legacy that continues to shape Texas even now.

Politicians make history for getting things done: they are wheeler-dealers like Lyndon Johnson, who bullied his way to his Great Society; or negotiators like Ronald Reagan, who bartered behind the scenes for social security reform; or persuasive orators like Barbara Jordan, who moved listeners with her eloquence during Nixon’s impeachment hearings. Less celebrated are the agitators, the men and women whose scrappy efforts on the streets—rallies, door-to-door canvassing, provocative rhetoric—have taught them that passion gets more done than diplomacy. Almost as soon as Graves reached the Capitol, it was clear what camp he fell into: longtime politicos still recall the day he stood on the press table to shout his questions at the speaker, or the time he dressed in a white suit, pulled a gun on the House floor, and fired a few rounds of blanks to underscore a point on gun restrictions. It had taken nerve to get to Austin’s marbled halls; that same nerve now made him seem, to some at least, stubborn, distracting, and crazy.

This is not a characterization that offends him, as I discovered one morning last summer, when I met him at his two-story brick house in the suburbs of Atlanta. When he opened the door to greet me, he seemed taller in person than in the black and white photos I’d seen. Since leaving Texas, in 1974, he had worked thirty years for NASA in Washington, D.C., and Langley, Virginia, before settling down in Georgia in 2003 to work as a photographer, and the walls of his home were decorated with large prints he’d had framed—scenic views of Venice, Florence, and elsewhere, evidence of a life well-traveled. The gossipy Texas political intel that was once his currency—Houston mayor Annise Parker’s potential as a gubernatorial candidate, for example—now trickled to him second-hand.

“I came up in a political black family in New Orleans,” he began, sitting in the dining room. “My father was always involved with the NAACP and civil rights.” Activists coming through town, barred from white hotels, often stayed at his parents’ house. “Thurgood Marshall slept in my bed while I slept on the couch—that’s a fact!” he said, noting that the same table before us was also where activists had eaten his mother’s gumbo.

For much of his youth, his parents tried to shield him from the laws of Jim Crow, refusing to acknowledge their existence so as to preserve his sense of self-worth. He was thus “raised in a cocoon,” though his daily reality was one of segregation: his classmates at Catholic school, including an impressive roster of musicians such as James Booker, Charles Neville, and Ernie K-Doe, were all black; the YMCA branch he attended—where his dentist’s son, a future congressman named Andrew Young, became his counselor—was for blacks; he lived on a block composed solely of black families. His mother, Mabel, a seamstress, covered up the institutional racism of the day with fabrications: she told her son that they sat in the back of the bus because it was cooler, or sat upstairs at the theater to see better, or avoided meals at department stores because the glasses weren’t clean.

As he grew older, and exclusion became impossible to ignore, Graves studied his father’s approach. Fagellio “Buddy” Graves, a successful service-station owner of African-Italian heritage, wore nice clothes, spoke his mind, and stood his ground. He also strategized: taking advantage of his fair skin, he sometimes opted to passé blanc to get a room at a whites-only hotel or asked the family to “lean in so they won’t see who you are” at the drive-in. (“He did what he had to,” said Graves.) In every situation, his father prepared for both the best and stomach-churning worst. When Graves was about ten years old, he learned that the police had shot a schoolmate in the back. “My dad sat me down and said, ‘Son, this is a lesson: Never run. Never turn your back on them,’ ” he recalled. “ ‘Make them shoot you in the face.’ ”

It was also his father who impressed upon him the importance of voting. Ignoring the right to vote, Buddy told his son, was akin to sinning. Once, in the fifties, the elder Graves even ran for the school board—not because he thought an African American in New Orleans had a chance but because a recognizable name of a black local would motivate his neighbors to register. With high enough numbers, he told his son, they could one day wield influence. Maybe they could even elect someone who looked like them.

Graves had planned on graduating from Xavier University, in New Orleans, but two years into his college degree, he changed course, in part to get away from his parents (“You know how kids are,” he explained) and in part because the dean of students had, after noting his C’s in math—his major—suggested he quit college and pursue manual labor. This advice did not sit well. “I left school that day, and I said, ‘I’m going somewhere else,’ ” he said. Graves enrolled at Texas Southern University on the recommendation of a mentor, and within a week, he had loaded a Samsonite full of clothes into his blue 1951 Mercury and headed west.

His decision would catapult him into history by luck as much as will. In the fall of 1959, when he arrived on the TSU campus, Houston was the center of the booming oil and gas industry; in the previous ten years, the city’s population had grown almost 60 percent. The main beneficiaries of the economic growth, of course, were white Houstonians, but no one had yet caused much of a public outcry over the city’s racial inequities. That began to change with Eldrewey Stearns, a TSU law student whom Graves met soon after arriving. Born in Galveston, Stearns, an accomplished debater, had recently become a campus celebrity after appearing before the city council during a weekly citizens’ forum called Pop Off Day to detail a beating he’d received at the hands of Houston police officers. He claimed his infraction was failing to call the officers “sir,” and his rebuke was so blistering that afterward, an up-and-coming reporter named Dan Rather interviewed him for that night’s news program, broadcasting Stearns’s criticism to every Houstonian with a television.

His boldness made an impression. “He was a brilliant young man,” recalled Earl Allen, then a TSU student and now a Houston church pastor. In February 1960 Allen and Graves attended one of Stearns’s early campus gatherings advocating for the city’s desegregation, a topic of particular resonance after the lunch counter sit-in by students in Greensboro, North Carolina, earlier that month. “He talked for thirty minutes, and I sat there and listened,” said Allen. “My response was, ‘You’re a genius or a damn fool. I think it’s going to take time for me to figure it out.’ ” Graves was similarly riveted. “Curtis saw me when I made a speech and everybody applauded me and said, ‘You’re telling the truth,’ ” Stearns told me. Now 83 and in an assisted-living facility, he still relishes questions about his activism. “Then Curtis became my lieutenant.”

Stearns, Graves, Allen, and a handful of other students formed the Progressive Youth Association (PYA), meeting frequently at TSU’s Hannah Hall to discuss how to go about desegregating Houston. The group was spurred to act in late February, when then-senator Lyndon Johnson declared that Texas “nigras” were too complacent to engage in political protest. “When [TSU undergrad] Holly Hogrobrooks brought the newspaper carrying his comments to 214 Hannah Hall,” wrote historian Thomas R. Cole in the Stearns biography No Color Is My Kind, “Johnson’s clever words hit their mark: the group immediately planned a sit-in for Friday, March 4, 1960.”

It would be the first sit-in west of the Mississippi River that year. At four o’clock that day, Graves, Stearns, and about ten other students assembled at a campus flagpole and began to march to Weingarten’s, a nearby supermarket that did not serve blacks at the lunch counter. Reporters from the Houston Post, the Houston Chronicle, the Houston Press, and the Informer, whom the students had called to document the encounter, were late—“We were afraid, because we thought that maybe somebody would do something to harm us, maybe the police,” Graves remembered—but when the press finally did arrive, along with more students, the PYA took all thirty seats at the counter. “They immediately shut it down,” Graves said. After all the white customers left, store officials tried to reason with the students, but they held their ground, remaining seated until the store closed. Their achievement made the weekend news.

Not everyone felt triumphant. “It was a fairly universal thing that parents wanted their kids to stay out of trouble with the law and go to college,” said the Reverend William Lawson, the founding pastor of Wheeler Avenue Baptist Church, who counseled and assisted the protesters throughout the sixties. “It was a whole new world for us.” Families reading about the mobs who were attacking student protesters in Nashville feared the same violence in Houston—a worry that appeared justified three days later, when two masked men forced a local 27-year-old named Felton Turner into their car at gunpoint, took him into a wooded area of Houston, beat him with a chain, and carved “KKK” into his abdomen. Earlier that day, the PYA had staged a sit-in at a Henke & Pillot supermarket lunch counter. Turner said the men claimed they had been hired to hurt him because “those students at Texas Southern University were getting too much publicity.”

But the scare tactic only galvanized the students. Just a day or two after Turner had found his way to a hospital, Graves led another sit-in, this time at a grocery store on Almeda Road. With the NBC cameras rolling, he jumped over a barricade and occupied a lunch stool. That night, as he was sitting in his apartment, his father called to say he’d seen him on the nightly news. He was not proud. “I didn’t send you to Houston to do this!” he shouted. Graves listened, considering how to respond. Should he yell back? Shame him? Like most twenty-year-olds, he hadn’t given his dad’s opinion much thought. Finally, he came up with a reply: “Dad, you raised me to do this.”

The pressure to end the protests began that same week. Mayor Lewis Cutrer, a Mississippi native who’d campaigned on a segregationist platform (one poster read, “Will the Negroes Rule Our City?”), insisted that the president of TSU, Sam Nabrit, intervene and spare the city from an embarrassing—or deadly—incident. Nabrit, an accomplished marine biologist whose brother, James, had been a prominent attorney in the NAACP’s fight against Texas’s white primary, was unsympathetic. “Sam held an all-university assembly, and I remember he spoke for five, ten minutes,” Graves told me. “He said, ‘Primarily, you’re citizens of the United States. Secondarily, you’re students. So you have to do what you have to do.’ That gave us carte blanche.”

Cutrer announced he was putting together a 41-member biracial committee to negotiate a compromise, a move that appeared favorable but quickly revealed itself to be a tactic to stall the sit-ins. Feeling they’d been tricked, Graves and Stearns decided they needed adult leadership, and for that, Graves had an idea. He called his old YMCA counselor Andrew Young, who since their days in New Orleans had become a right-hand man to Martin Luther King Jr., and Young put the two students in touch with King himself. Excitedly, they requested advice from the reverend about reviving enthusiasm among students for their cause. “I talked for about twenty minutes—Eldrewey and I, both of us talking,” Graves said, “and when it was over, King paused, and he said, ‘I’ll tell God about it.’ And Eldrewey and I looked at each other like, What the hell? And we said, ‘Thank you,’ and hung up the phone and said, ‘We’ve been had!’ ”

Unbeknownst to them, however, a group of Houston’s black leaders—an assembly of businessmen, religious advisers, and community members—was already meeting with the city’s white leadership in an effort to stave off the kind of police aggression affecting other states. “There were probably six or eight meetings,” remembered Reverend Lawson. Lawson attended the gatherings along with Quentin Mease, a former World War II Air Force captain who was the executive director for the South Central YMCA, which had become the headquarters for the TSU activists. “The feeling was that if Houston was going to have a major league baseball team with a dome stadium, and if it was going to have a space center, if it was going to be the oil and gas capital of the country, and if indeed Houston could move companies like Exxon to Houston, then it couldn’t possibly have a Bull Connor or have the type of things that happen in Birmingham, Alabama,” said Lawson.

Slowly, over the next couple of years, the city began to desegregate lunch counters and hotels without fanfare. Yet for the students, this wasn’t enough: other businesses remained segregated, especially theaters and restaurants. Their best hope for wholesale change, they felt, was to stage a major disturbance. In May 1963, as police in Birmingham were assaulting protesters with water hoses and attack dogs, the PYA devised a plan: they would interrupt a homecoming parade scheduled for Houston astronaut Gordon Cooper with a demonstration that would catapult them into the national spotlight.

Catching wind of the protest, Mease alerted city leaders like Houston Chronicle publisher John T. Jones and Foley’s vice president Bob Dundas, hoping that news of the students’ plan would force their hand on desegregation once and for all. Then he awaited a response. “What was finally decided was that they would desegregate restaurants and department stores and all the Houston transit authority in one day, and none of the major media—the Post, the Chronicle, the television stations—would mention it,” said Lawson. No mobs could convene over events that weren’t publicized.

On May 23, the day of the parade, just minutes before 300,000 onlookers were to cheer the floats down the streets, Mease contacted Stearns and told him the terms he had exacted from the white business owners. The students were shocked. “Our signs were ready,” Graves said. “I was at the coffee shop at the Y when Eldrewey came in and said a deal had been struck.” Though they could have gone ahead with the protest, Mease cautioned against it. Desegregation would begin in thirty days, he told the students—so long as they stayed home.

No one in Houston could have conceived such an anticlimactic moment. As promised, thirty days after the parade, the city changed forever, yet no one reading local headlines would have known. Without any announcement or celebration, “white” and “colored” signs were quietly taken off buses and drinking fountains. At department stores like Foley’s, where black customers hadn’t been allowed in fitting rooms, greeters now asked, “Would you like to try on a dress?” Black shoppers, startled, conferred with friends and neighbors, wondering how the city had transformed in one day. It wasn’t until a week later, when outside media learned that Houston had desegregated, that the city’s conversion was made public. In the end, the city’s DNA had proved stronger than rhetoric. “We won the battle,” said Graves, “because the dollar was more important than race.”

But for someone like Graves, who had put all his thoughts and energies into radical change, integration was just a start. The PYA, now bereft of purpose, disbanded, and he and Stearns parted ways. Graves graduated that spring and went to work as the manager of a new branch of the Standard Savings and Loan Association, owned by Mack Hannah, a three-hundred-pound, cigar-smoking millionaire. “He was loud, he was aggressive, he was as smart as they come—and crafty,” said Graves. A force in Houston’s black community, Hannah saw a physical resemblance between Graves and his own son (“We could have been twins,” said Graves) and took him under his wing as his protégé.

Graves wasn’t thinking of a political future, but Hannah could detect his zeal, and a few months after the young graduate started work, the banker asked Graves to drive him out to Lyndon Johnson’s ranch for a party. “Here is Earl Warren and all these people who are on the Supreme Court and the Cabinet members and Connally—who’s got his arm in a sling because he had just gotten shot,” recalled Graves. Observing politicians in their element—hashing out deals, tossing around “MFs” and “SOBs”—was a revelation, and a few years later, in 1965, when a lawyer friend from the Fifth Ward named Asberry Butler asked him for help in a school board campaign, he felt inspired to get involved.

Considering that school board members had to be elected at-large—a system in place since 1876 that diluted the minority vote—Graves devised a strategy based on name recognition: it just so happened that his friend shared a last name with a long-serving white member of the board, Joe Kelly Butler. “If we can craft our campaign so we never show up at a white rally, we never allow a picture of you to be in the papers, we never do anything in white Houston, and we only campaign in black churches,” Graves told Butler, “the white folks will think that you are Joe Kelly Butler, the black folks will know who you are, and you’ll win.”

The gamble worked: Asberry Butler became the second African American after Hattie Mae White to sit on the school board. One can only imagine Joe Kelly Butler’s surprise to discover that people had voted for a black candidate thinking it was him. For Houston’s African Americans, however, the win was less of a shock. After Smith v. Allwright, black Texans had registered to vote in droves—more than in any other Southern state—and with the passage of the Voting Rights Act and a push for voter registration by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, turnout was at a record high. On a visit to the Capitol around this time, an exhilarated Graves realized he was ready to become a candidate himself. “I decided either that day or the next that I was going to run as soon as there was a possibility,” he told me. It didn’t hurt that just a year earlier, in the 1964 case Kilgarlin v. Martin, a federal court had forced Texas to redraw its electoral map in accordance with a U.S. Supreme Court decree that states’ legislative districts should be based on population size, not land area. There were now three multimember districts in Harris County, where only one at-large district had stood before.

Graves decided to run for a seat in the House. “Hattie Mae kind of groomed me and said, ‘These are the things you need to get it done,’ ” he told me. His first step was to clinch the backing of the Black Ministerial Alliance and a black coalition known as the Harris County Council of Organizations, which, in turn, persuaded several labor groups—who were also behind Lauro Cruz and Barbara Jordan—to support him. Jordan would have the easiest time attracting votes; after graduating from TSU a decade earlier, she had worked on voter registration in Houston for the Kennedy campaign and was a well-respected lawyer who preferred pragmatism over activism. Graves, meanwhile, was barely out of college, with a reputation for grassroots rabble-rousing. “If you compared them to a family,” explained Cruz, “Barbara was the daughter and Curtis was the cousin.” But Graves was not discouraged. As he saw it, his work to desegregate Houston merited attention too. “I remember when I was working at Standard Savings,” he told me, “a fella came in and said, ‘People who succeed in towns are not usually from that town.’ He told me, ‘Jesus didn’t make it in Nazareth; he needed to go somewhere else.’ ”

The more experienced Bob Eckhardt helped Graves and Cruz formulate a plan to campaign together—though Graves decided, after a few outings, that it was best if he kept a low profile and spoke last at white events. “I would always say, ‘I’m the mop man in the delegation.’ I didn’t want to portray myself as a threat to anybody,” he said. Sometimes this meant biting his tongue, as he did during a police meeting in which officers screened a film about the 1965 Watts riots that he felt “glorified the White Citizens’ Council as the savior.” Other times it meant accommodating casual racism. At one fundraiser, he walked into a room behind Eckhardt’s wife, Nadine, holding the couple’s young daughter, Sarah; when his friendly acquaintance Barbara Bush noticed people staring, she whispered to him, “You give Nadine that baby now.” As Eckhardt entered the room, Graves told him to kiss Nadine and make clear to everyone that Graves was just a friend.

That following fall, on the night of the general election, Graves attended a celebratory gathering at Eckhardt’s headquarters. He and Cruz and Eckhardt had won handily, as had Jordan. It was history in the making, and now, Graves discovered, their supporters wanted to pretend these had been inevitable wins rather than victories fought for by several generations. At the party, Graves received a congratulatory call from President Johnson. The next morning, he accepted media interview requests and posed for photographs. Time published a story headlined “Texas: A Quiet Change.” More than two decades after fighting against the state’s all-white primaries, Lonnie Smith might have had something to say about that.

This past April, almost fifty years after he took his first step into the Texas House of Representatives as a member, I visited the Capitol with Graves. On the fourth floor, he walked north of the dome and pointed to one of the large, ornate wood doors. “So I was right here,” he said of the office he shared with Cruz. He opened the door to an office that now belongs to Houston representative Gary Elkins. Two young people in the receiving area looked up from their desks long enough to say hello, then returned to their work. Graves touched a spot on the door and said, “We had a little sign right here: ‘If the knife don’t get you, the razor will.’ ” He laughed. The Elkins staff did not react.

To imagine what it was like to enter the Legislature in January 1967 as a black Texan, it helps to remember that the most recent African American in the House before Graves was Robert L. Smith, of Colorado County, who served from 1894 to 1899 and argued passionately against the era’s rampant lynchings. It had been 68 years, in other words, since there had been a black representative, and legislators required some adjusting. “The n-word was as common as ‘sumbitch,’ ” said A. R. “Babe” Schwartz, who served in the House and Senate between 1955 and 1981. “Up until the early sixties, every statewide official was a segregationist publicly.” Shortly after Graves took office, he was joined in the House by Joe Lockridge, an African American from Dallas, whose arrival had been delayed for various reasons. But any potential for a black caucus was hindered by a clash of personalities. Lockridge, a lawyer and conciliatory type, was in Graves’s estimation too conservative; Senator Jordan, meanwhile, made no overtures to the two men, not even for coffee.

Instead, Graves made headlines by desegregating the legislators’ dining spot, the Austin Club, and endeared himself to the press. But it quickly became clear that the skills that had set him apart as an activist—his directness, his penchant for confrontation, his demands—were a liability when it came to being a politician. He became known as a militant with biting humor, even telling one reporter he didn’t expect trouble at the Capitol because he had an outgoing personality and could “tell nigger jokes like anyone else.” Once, when the voting machine on his desk went missing, he nodded toward Lockridge and suggested sarcastically, “Check that other black guy. You know how they all steal.”

He’d arrived wanting to facilitate change: to include a more accurate depiction of the African American experience in school textbooks, to outlaw DDT, to institute a minimum wage. But his belligerent style and reputation as a radical made him politically toxic. “If I said I was in favor of a bill, it wouldn’t pass,” he told me. It wasn’t until the end of the session that Graves found a way to channel his passion: he pretended to work against a bill or even played the court jester if that’s what it took to get things done. In one instance, he talked a conservative legislator with a special-needs child into fronting a bill to help find homes for hard-to-place foster children; in another, he came to the rescue when Lockridge presented a bill that would allow chicken to be sold in pieces, an effort to bring Kentucky Fried Chicken franchises to Texas. As Lockridge was speaking, Graves saw that House members were about to ridicule him and intervened: he asked for amendments to allow watermelon to be sold by the slice and possum by the piece. “The House just screamed and yelled, and they were rolling on the floor, and I walked away,” Graves said. “I think they were going to try to take him apart, make a fool out of him. Instead, everybody laughed, and boom, they passed the bill.”

In May 1968 Lockridge died in a plane crash and was replaced by a politically reluctant African American pastor from Dallas named Zan Holmes. “When I met Curtis Graves, he was tall, good-looking, very intelligent, gifted, had a big ego,” Holmes remembered, laughing. “I mean self-confident!” Graves, in turn, continued advancing his agenda. “Curtis had me out presenting his bills as my bills, and he went around pushing it,” said Holmes. “He was the one driving that train. Remember, I didn’t want to be there.”

Graves told the New York Times that black legislators “have got to understand our role. We’re educators, not legislators. That’s about all we can do at this stage.” Yet he believed even greater things lay ahead for him, and in 1971, after being reelected for a third term in the House and making a failed run for Houston mayor, Graves turned his sights on the Senate. Jordan, he knew, was eyeing a seat in Congress, which would leave her Texas seat open. And he was well-positioned to succeed her: Jordan had endorsed him in his mayoral run, and by now he had some prestige and name recognition among voters. For all the maneuvering he’d had to learn, he’d adhered to his principles. (“Seldom did anyone approach me and try to get me to go in another direction, because I didn’t do that,” he said.) He’d even become part of the Dirty Thirty, a respected group of Democrats and Republicans who forced a bribery conspiracy investigation into the Sharpstown stock-fraud scandal that effectively ended the careers of Governor Preston Smith, Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes, and Speaker Gus Mutscher. This was his moment.

He would be sorely disappointed. The 1970 census had led to a new redistricting map, and as lines in Houston were redrawn, the district that had elected Jordan was carved up, splitting the black vote—and making it almost impossible for Graves to win. Furious, Graves suspected that Jordan, who had been appointed by Barnes as vice chair of the Senate redistricting panel, had conspired with the lieutenant governor to shut him out, giving up the one Senate seat available to Houston’s blacks in return for a congressional seat for herself. “She put my house in the district that included River Oaks,” he said. “I called it ‘the fickle finger district’ because it had a little finger that went down and got my house.” Whether his suspicions were correct has long been debated: Barnes denied shutting Graves out on purpose, and his chief of staff, Robert Spellings, told me that Graves had no impact on how the map was drawn. But the 2000 biography Barbara Jordan: American Hero quotes several late legislators, including Eckhardt, with opinions to the contrary. “I was in Ben Barnes’s office when he said the Senate was determined to not let Graves in,” said Eckhardt. “It was not Barbara’s trade-off. Graves was rather flamboyant and they didn’t want him.”

Graves waged war. “I was so pissed I didn’t know what to do,” he said. Since their earliest days at the Capitol, he had seen Jordan as an insider who consorted with the enemy—the white establishment—and compromised too eagerly on causes that affected their constituency. Unlike him, Jordan was not the type to fall on her sword; she aligned herself with those in power, she bartered, and she fought battles she could win. Jordan passed a bill for a $1.25 minimum wage, for example, and negotiated with lobby groups to increase workers’ compensation, but for Graves, these numbers were pathetically low; when she filibustered for an hour against a bill to raise taxes on food, in 1969, Graves suspected that she’d then secretly helped end the same filibuster, allowing passage of the bill. (Years later, Barnes acknowledged this was the case.) Now Graves decided to campaign against her for the congressional seat. Using every rhetorical barb in his arsenal, he went on the offensive, denouncing Jordan in the press as the “Aunt Jemima of politics.” In a nod to the Sharpstown scandal, he declared that he could function “more independently than she of the Texas Democratic party and its controversial bosses.”

Jordan resisted counterattacking. “If the district is looking for someone who just raps,” she calmly told the papers, “I’m not the one. If it’s performance that counts, then I’m the one.” Ever popular, she raised five times as much money as Graves did and got Johnson’s support; in October 1971 newspapers published a photo of the president embracing her at a fund-raising dinner at the Rice Hotel. (“That sealed the deal,” Graves said.) She received 80 percent of the vote. Graves, humiliated, told the New York Times that Jordan had “sold out to downtown money.” Though black leaders would try to smooth over his and Jordan’s relationship, their efforts failed, and even today, Graves has few kind words to describe her. “I had a difficult time,” he told me.

Graves left Texas, shaking off the dust of politics for good. “Unfortunately, there are persons who played in the NBA with Michael Jordan who were great stars, but he was the one to beat,” Houston congressman Al Green told me. “Curtis, as great as he was, he just ran up against the Michael Jordan of his time.” Reverend Lawson agreed. “He was a protester,” he said. “I don’t think he ever really did become a politician. And politicians and protesters are not synonymous.”

There’s a role for agitators in society. “It’s an admirable part of this country’s history and culture,” said Don Carleton, the executive director at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. “Sometimes they do it for show and their own notoriety—those would be the demagogues—but others are trying to do something and can’t get attention otherwise. Graves wasn’t a demagogue. He had a cause to move forward, and that was to get the establishment to recognize the rights of his constituents in the Fifth Ward.”

It was Barbara Jordan, of course, who would then take that baton and run with it—who would gain national recognition in 1974 at the Watergate hearings; who would extend the Voting Rights Act to Texas in 1975, requiring Spanish-language provisions at the polls; who would help pass the Equal Rights Amendment of 1977 and the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, forcing banks to provide lending services to minorities. It was Jordan who would rise to the stature that Graves once sought. And yet, by playing her foil, by raising a ruckus, he undeniably paved the way for those with a long view of African American political power in Texas.

Back at Graves’s house, I asked him if he ever regretted his hard-line approach. He didn’t hesitate. “I don’t,” he said.

“How do you think history is going to view you?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said.

“How do you hope it will view you?” I asked.

“Well, I hope that people will understand that I had the integrity to stand up for what I believed,” he said. “In many cases, you pay a price for that, and I think I did.”

This year, two African Americans are running for Houston mayor: former state representative Sylvester Turner and attorney Ben Hall. Some believe that the city’s first black mayor, Lee Brown, who served three terms starting in 1998, would have had a more difficult road to office if not for Graves; by running for mayor in the first place, Graves got people used to a once far-fetched idea. And his entry into the House blazed the trail for a succession of black Houston legislators. “He was a mentor for Mickey Leland and myself, for sure,” said Craig Washington, who served in the Legislature from 1973 until 1989, then in the U.S. House of Representatives until 1995. “You could trace the lineage of almost anyone who serves now and you’ll find that at some point before they were elected to the House or Senate, they started out by licking stamps and learning campaign techniques in Houston.”

Senator Rodney Ellis, who was threatened with expulsion in high school for wearing a “Vote Curtis Graves” button, remembers too. “In school, I read in the newspapers that they wouldn’t acknowledge him, so he jumped on a table,” he said. “Later, there were times I made the comment to Governor Bullock, ‘If you try to silence me, you’d better be prepared for me to jump on the table.’ It had an impact on me as a young African American male who never dreamed I would end up in the Legislature.” Turner agrees. “The activist enables the negotiator to be successful, and Graves played that role. We needed an agitator, and he made it possible for others to be diplomatic.”

Outside the Capitol rotunda, in the south entryway, a large poster displays photos of all the black Texas legislators who served from 1868 until 1900. Passing by it during my visit with Graves, I pointed out Robert L. Smith’s photo. “This was the last guy to serve before you,” I noted. In the photo, Smith is wearing a white necktie, his mustache stretching to his chin; he looks young. Graves bent close for a better look. Then his attention drifted to the other portraits. “Look at all the black faces: one, two, three . . . twelve—I didn’t realize there were so many during Reconstruction.” As his eyes wandered, it became clear that he was searching for his own mark in history. He began reading a plaque beneath the poster: “ ‘. . . not until 1966, with the election of Barbara Jordan of Houston in the Senate and’—aha! There I am!” he said. “I’ll be damned.”

The type was no bigger than that on a return-address label. There was no portrait of him in the House chamber near that of Sam Rayburn, no mention of his civil rights work, nothing to distinguish him save the composite photos of House members between 1967 and 1973, in which his difference, in the sea of white faces, was obvious. He’d embraced his unique fate, one he might not have imagined when he first put on a suit and tie, stood in the voting line, and answered a white woman’s questions about the Constitution. “Somebody had to be the Stokely Carmichael of the group,” Graves said. “Somebody had to be the rabble-rouser. And that was me.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads