IF THE SEVENTY-FOURTH LEGISLATURE COULD VOTE on the best lawmaker of 1995, the likely winner would be not one of its own but Texas Supreme Court justice John Cornyn. His January 30 opinion upholding the constitutionality of the state’s school-finance law saved the session. It took off the table the one issue that could have required a tax increase or massive budget cuts. For once the legislative agenda wasn’t driven by the courts.

The new candidates for chauffeur, in keeping with the electorate’s sharp turn to the right last November, were the governor and business. George W. Bush wanted to honor his campaign promises about education, welfare, juvenile crime, and lawsuit reform. Business wanted everything else: tax breaks for oil companies, subsidies for sports stadiums, monopolies for liquor interests and utilities, friendly regulations for banks and insurance companies, and protection from unfriendly regulations on developers and polluters. As one legislator said, putting a twist on a Bush campaign line about Texans, “What lobbyists can dream, lobbyists can do.” But it turned out they couldn’t. The business agenda never found a champion, and Bush wisely didn’t volunteer. He wasn’t about to endanger his own program by adding controversial items to his wish list.

Bush’s four issues, along with the state budget, absorbed most of the Legislature’s time, energy, and talent. The old maxim that you can do what you’re big enough to do was out of date; the new rule was that you could do what you were in a position to do. Almost all the major initiatives were carried by committee chairmen who fashioned the bills themselves or negotiated the language in back rooms. Ordinary legislators could do little more than pass noncontroversial bills and cast votes. Their awareness of their own irrelevance made them passionless, and that attitude became the dominant mood of the session.

This atmosphere made our selection of the Best and Worst legislators more difficult than usual. There were fewer players to choose from and fewer chances for them to make a difference. Our criteria for the Best list changed a little. We still placed great weight on integrity, effectiveness, fairness, and a willingness to put public policy ahead of partisanship and personal ambition. But we also looked for legislators who far surpassed the level at which they were expected to perform.

On the Worst list, we looked first for legislators who did great harm. But the opportunities to inflict damage were scant this session; the major issues had such strong bipartisan support that no amount of tomfoolery or skulduggery could affect the outcome. What we did find was a lack of respect for the basic values of politics: compromise, good faith, and a commitment to the public trust. Even John Cornyn can’t save the Legislature from all its problems.

The Best

A Done Deal

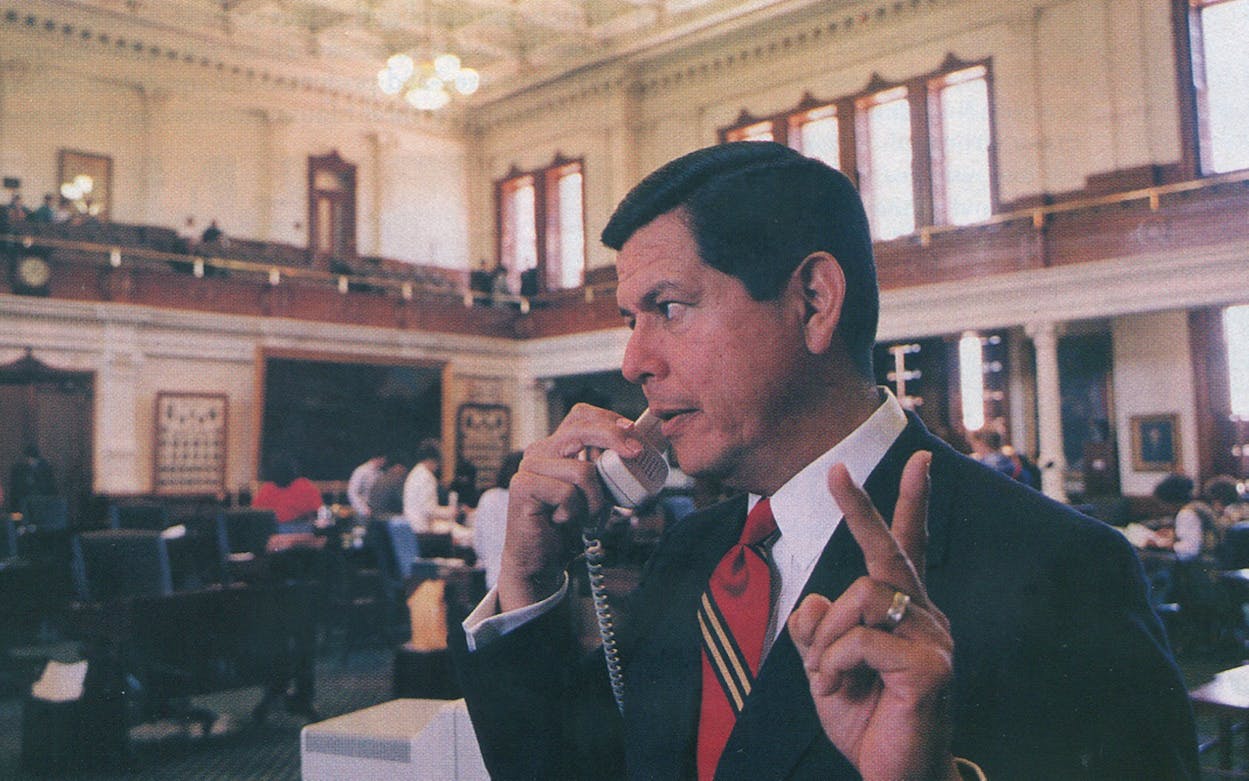

Hugo Berlanga

Democrat, Corpus Christi, 47. It’s easy to locate Hugo Berlanga’s desk on the House floor. His is the one with the chair that’s always empty. He may be working the floor, he may be conferring in his office, he may be in the Senate, he may even be in the governor’s office, but wherever he is, you can be sure of one thing: He’s cutting a deal. He could find common ground between heaven and hell.

Berlanga has one of the toughest assignments in the Legislature: chairing the House committee on public health, an area that a medical lobbyist aptly describes as “technical and turfy.” It is a legislative Balkans of warring factions—doctors, nurses, chiropractors, pharmacists, hospitals, insurance companies—and Berlanga is a one-man peacekeeping force. During negotiations on a mammoth bill overhauling Medicaid, lobbyists for health maintenance organizations marched into his office determined to convince him that the bill would be too costly unless Medicaid patients were limited to seeking treatment from a small group of health care providers, mainly primary-care physicians. The lobbyists marched out agreeing with Berlanga to expand the group to include chiropractors, dentists, optometrists, and the like. As the sponsor of a bill to improve rural health care, he ended an impasse by getting doctors to let nurses and physician’s assistants write prescriptions. An unwritten part of the agreement is that Berlanga-Has-Had-Enough clause, in which each side has concurred that it will not try to change the bill next session unless the others are in accord.

When Governor George W. Bush failed to name a Hispanic to the University of Texas Board of Regents, the logical assumption was that he was on a collision course with Berlanga, who is the chairman of the Mexican American Legislative Caucus. Instead, they ended up pals. Berlanga told the governor how to approach his meeting with the caucus: Take control of the agenda by talking about your firm stand against California’s Proposition 187. The meeting went well, and the next thing you know, a Berlanga buddy gets a gubernatorial appointment and Bush decides that maybe Berlanga’s coastal zone management bill, with a few changes, might not be so bad after all.

Berlanga is the kind of legislator whose career makes a good case against term limits. He came to the House in 1977, and for most of the eighties he was close enough to then-Speaker Gib Lewis that he was assured of having influence whether he performed at a high level or not—and often he did not. Now that he can succeed only by using his wiles and experience, he is a far better and more valuable legislator—so good in fact, that he is the only member of the House to make the Best list in 1993 and 1995.

Hero

Garnet Coleman

Democrat, Houston, 33.The Legislature produces good guys and bad guys, idealists and cynics, political sophisticates and political naїfs, but it seldom produces heroes. Garnet Coleman is a hero. He came further than any member of the Legislature this session, or perhaps any session—not just from the obscurity of the House rank-and-file but also from the depths of depression in a Houston hotel room last September, he whereabouts unknown even to his family.

After learning to cope with the death of his father, prominent Houston physician John B. Coleman, he regained his own health and began attending to the health of others. As a member of the House Appropriations Committee, he won an increase in children’s mental health funding and tackled the long-standing issue of how to apportion funds for the mentally ill between rural and urban areas. Coleman jiggled with the formulas to get more money for the cities—where most of the problems are—and presented his committee colleagues with a letter signed by rural House members agreeing to the change.

Coleman represents a breed of politician the Legislature hasn’t seen since Barbara Jordan left for Congress in 1972: a black inside operator. He never sells out black interests, but he does frequently disagree with other blacks on what black interests are. When most blacks were fighting the welfare reform bill, Coleman was co-sponsoring it and defending it in floor debate. “The way welfare is now, it doesn’t do anything for anybody,” he told the House. When a black colleague offered an amendment to let welfare benefits rise with inflation, Coleman said, “I would love to accept this amendment, but it’s a budget buster.” He felt that the state’s money could be better put to use in programs like job training and day care for the working poor and held meetings at seven in the morning to look for ways to increase funding. When intransigent bureaucrats said that Coleman’s plan to get more federal day care funds wouldn’t work, he told them: Tell me why it won’t work and I’ll get it fixed. And he did.

At first House elders worried that Coleman was driving himself too hard, but the more work he undertook, the more he seemed to thrive. Speaker Laney rewarded his efforts by naming him to one of the five coveted slots on the committee that negotiated the final state budget with the Senate. The appointment was the capstone to a session that saw him lead not only on health and budget issues but also on education: A Coleman floor amendment restored the 22-to-1 student-teacher ratio to the House bill. About the only disappointment Coleman suffered was the failure of his proposal to raise taxes on Houston car rentals to fund downtown redevelopment. When his last-ditch efforts lost, Coleman was visibly miffed. That’s when Speaker of the House Pete Laney leaned over the podium to whisper some advice. “Don’t get testy, Garnet,” he said. “You’ve come too far to blow it now.”

Not Newt

Tom Craddick

Republican, Midland, 51. Surprise, Surprise. The long-time chairman of the Republican Caucus molded a collection of Newt Gingrich wannabes into a constructive force and became Governor Bush’s floor leader in the House. After a career spent throwing roadblocks in the path of Democrats—and getting tax breaks for his oil buddies back home—Craddick spent this session keeping GOP hard-liners from disrupting the bipartisan atmosphere that was essential to Bush’s success—and getting tax breaks for his oil buddies back home.

The old Craddick delighted in forcing Democrats to cast votes that might prove embarrassing at election time. The new Craddick decided that Bush’s legislative program was more important than partisan warfare. The signal that things would be different his year came when caucus hard-liners offered an amendment to toughen the first tort reform bill, which Bush had endorsed after weeks of negotiations. Faced with a familiar dilemma of politics—whether to be guided by philosophy or pragmatism—Craddick chose the latter: better to defend what Bush had already won than to try for more and risk ending up with less. The caucus did not embrace the amendment, and many Republicans joined the large majority of the House that voted it down.

Craddick’s influence wasn’t limited to running interference for Bush. When other caucuses were claiming to be exempt from ethics rules requiring disclosure of contributors, he backed a reform to plug the loophole. A prolific sponsor of bills, he passed what will surely be one of the most popular measures of the session, providing that drivers ticketed for going up to 70 miles per hour on rural highways will not suffer higher insurance rates.

His slender frame and mild manner belie a toughness and a political savvy that enable him to navigate the currents of the 62-member caucus. Never was his skill more evident—or more needed—than on the final Thursday, when the governor’s number one issue, education reform, was in trouble. Buried in the final version of the bill was a provision that relaxed safeguards against excessive local property tax increases. Even mainstream Republicans were vowing to oppose the entire bill if the safeguards weren’t restored. Without GOP votes, the bill was doomed. But changing the bill was dangerous, to say the least. The House would have to debate whether to return the bill to a conference committee with the Senate, Democrats would air their own grievances about the bill, and the support for the whole reform package could collapse. Craddick came up with the solution: attach a compromise restoring some of the safeguards to one of his own bills, which could be passed without refighting all the education battles. No member of the Legislature did more to assure Bush’s success this session than Tom Craddick.

Beating the Odds

Rodney Ellis

Democrat, Houston, 41. Forced to play the game with the deck stacked against him, Rodney Ellis beat the odds and won. He somehow found a way to pass legislation benefiting minorities through the most conservative senate since the one-man, one-vote era began in 1965. Republicans had established a new high-water mark with 14 of the 31 senators, and most of the 8 white Democrats voted conservative too. Ellis also had to contend with Senate tradition, which requires that two thirds of the members agree to debate a bill before it can reach the floor. So he operated mostly be amending other senators’ bills—a process that requires only a majority vote. Not just any bills would do; he needed those that were all but certain to pass. So the welfare reform bill that was a gubernatorial priority became a vehicle for Ellis’ plan to reorganize job-training programs. When a Bush-backed tort reform bill came along, he rounded up the votes to block debate on the main bill unless its backers agreed to accept his amendment allowing lawsuits against insurance companies that redline, or discriminate against, property owners in poor neighborhoods. He didn’t always resort to amendments; he passed a groundbreaking reform bill limiting campaign contributions in judicial races.

Parliamentary skill alone does not explain Ellis’ success. He is a member of the Club, an unofficial group of elite senators who conduct themselves the way that elite senators are supposed to: Toughness is good, shrillness and criticism are not, and humor is essential. Ellis fits right in. When fellow Club member David Sibley of Waco proposed a state constitutional amendment to bar affirmative-action programs, Ellis said “no comment” to reporters, adding that he would have a written statement after he calmed down. He also has a knack for pithy observations that bring relief to tense debates. During a committee hearing on the telecommunications bill, with the Senate chamber crammed with lobbyists, Governor Bush escorted his father through the room. As the crowd ogled the former president, Ellis asked, “Did Southwestern Bell hire him too?”

For all Ellis’ skill and success, however, a trace of skepticism about him remains in the Senate. The knock against him is that he goes overboard on the issue of guaranteeing contracts for minority-owned firms, known as HUBs (historically underutilized businesses). He even tried to force HUB requirements into a noncontroversial city planners’ bill sponsored by GOP senator Bill Ratliff, who had supported two of Ellis’ most important bills. When Ratliff took him to task for holding up such a minor bill, Ellis relented. It has not escaped notice that Ellis is the majority owner of an investment banking firm that is a state-certified HUB, and while the firm does no business with the state, it certainly benefits from a political climate in which HUBs are regarded as a proper means of doing business. Rodney Ellis cannot stop the national debate over affirmative action from affecting Texas. He will not continue to command respect in the Senate if he tries.

Number Three

Patty Gray

Democrat, Galveston, 48. Before Patty Gray came along, only two women had appeared on the Ten Best list in ten sessions of ranking the Legislature: Sarah Weddington in 1975 and Lena Guerrero in 1989. One reason, of course, is that until recently there haven’t been very many women in the legislature. Another is that the Capitol is still a boy’s club, and women haven’t had much opportunity to take the lead on major issues. But it is also true that most women haven’t tried.

In the past, this is one of those late-night topics that members and lobbyists chat about over coffee after a long committee meeting. Not this year. Gray was the star of the sophomore class, the newest member with the brightest future. Already she has been a major player on budgetary issues, the environment, education, prisons, and horse racing. While she hasn’t been around long enough to have power, she has plenty of influence.

As a member of a special House committee looking at a Senate plan to halt auto-emissions testing, Gray decided early that the state couldn’t just ignore its contract with the testing company, Tejas Testing Technology. The House followed her lead and authorized a loan to Tejas during a moratorium on testing. She was the key player in the passage of a controversial environmental audit bill that gave companies incentives to report their violations of pollution laws. First she toughened it with floor amendments; then, when the sponsor was fumbling the debate, she rode to the rescue, taking over the defense of the bill in her anchorwoman’s voice. Once again the House followed her lead and it passed.

Gray sponsored two of the session’s most hotly contested bills: a rewrite of horse-racing regulations, which evolved into a struggle over whether Texas should have off-track betting, and a pension bill for retired teachers. Under intense time pressure, Gray weighed her personal antipathy for gambling against the economic woes of the racing industry and decided that a bare-bones plan for off-track betting was justified. But it didn’t reach the floor until just minutes before the final deadline, and anti-gambling forces talked it to death.

Her pension bill for retired teachers—which as usual was a fight between teachers who had retired recently and those who had retired long ago—had a happier ending. It gave retired teachers the biggest increase in benefits they had ever received, and the most money went to those who’d been retired the longest, many of whom were living near or below the poverty line. When it passed, Gray spoke to former teachers in the gallery: “This day has been a long time in coming.” In more ways than one.

Take That Hill

Rob Junell

Democrat, San Angelo, 48. How good was Rob Junell this session? He accomplished things no other House member in recent memory had done. He was a star in the House—as chairman of the Appropriations Committee, he assembled a budget that received an unheard-of unanimous vote—but he also managed to be a star in the Senate, where House members are usually about as welcome as termites. Invited to join backroom Senate negotiations on tort reform, Junell made the key decisions on the two most important bills in the reform package: setting limits on punitive damages and deciding who pays damages in cases involving several defendants. “He was like having a thirty-second member of the Senate,” says Lieutenant Governor Bullock.

Junell earned his unanimous vote on the budget by putting education first (“We listened to your priorities,” he told the House) and insisting that the financial shenanigans used to balance the budget in recent lean years be eliminated. Even after the budget was adopted, Junell continued to stand guard against raids on the treasury. He made the clinching arguments in a floor fight to eviscerate a bill that would have let school districts grant property tax breaks to industries and then get reimbursed by the state. Warning the House how much the bill could cost, Junell said, “We could have done a lot of good for $73 million.”

Junell’s more relaxed attitude was central to his success. Described as a “feisty fireplug” when he was honored as citizen of the year last February by the San Angelo Chamber of Commerce, the former Texas Tech linebacker seemed to smile more and lose his temper less than in previous sessions (although he humorous baseball cards that Senate staffers made up for budget writers noted that he had “beaned five agency directors”). “He acts tough, but he’s a soft touch for members with a problem,” says John Montford, his budget counterpart in the Senate.

Unlike most politicians, Junell is aware of his weaknesses. “Montford is more of a statesman,” he says. “I’m different. If you tell me to take the hill, I’ll take the hill. But if you ask me, ‘Should we take the hill? Should we go around the hill? Why this hill? I can’t help you.” Fortunately for Junell, the Legislature always has more hills to take but never enough people who can take them.

The Gold Standard

John Montford

Democrat, Lubbock, 52. With his fourth appearance on the Ten Best list, Montford ties the record held by former senators Babe Schwartz and Ray Farabee. He is the only legislator who makes the list not just for what he accomplishes but also for what he represents, which is the gold standard of what a senator ought to be: deliberate, fair, utterly unflappable, totally prepared; a sponsor of major bills, a guardian of the purse strings, a watchdog for sloppy legislation, and a soother of crises.

As the Senate’s chief budget writer and negotiator, Montford pinched pennies from regulatory agencies to keep money in reserve for colleges and universities. His trickiest problem was finding the funding for new medical clinics in South Texas, whose often-feuding senators regard the competition for pork as an Olympic event. Montford whittled $100 million in requests down to $24 million and still managed to divvy up the pot in a way that made all the contestants feel as if they were going home with a medal.

He passed a major tort reform bill limiting forum-shopping by lawyers trying to get their cases before friendly judges (getting the language right, Montford said, was “like trying to shake hands with an octopus”) and a death penalty reform that speeds up the appeals process but also provides attorneys for indigent death row inmates. He was one of the few senators who worked as hard on his colleagues’ bills as he did on his own. Two such bills that were on the fast track—one to allow landowners to sue the state over regulations that diminished the value of their property, the other to let professional sports teams build new stadiums with state tax dollars—screeched to a halt when Montford amended them to limit their effects on the state treasury. When minorities and Republicans reached an impasse over an affirmative-action provision, he led an effort to resolve the problem, going through six drafts before finding language acceptable to both sides.

Like a driven piano student who has to be shooed outside for fresh air, Montford loves nothing more than playing the legislative process. He is widely thought to be considering a race for lieutenant governor if Bob Bullock retires in 1998, and there was a little grumbling in the Senate this session that his statewide aspirations had made him more cautious than usual. He seemed much like the Montford of old, though, on an evening in late May when he leaned against the brass rail by his desk and said to an onlooker, “There’s no place else I’d rather be.” Except, perhaps, in that big chair on the podium, just a few feet away—but oh, so far.

A Perfect Team

Bill Ratliff and Paul Sadler

Bill Ratliff—Republican, Mount Pleasant, 58. Paul Sadler—Democrat, Henderson, 40. Hercules slew the Hydra, cleaned the Augean stables, and brought back Cerberus from the underworld. Big deal. Bill Ratliff and Paul Sadler rewrote Texas education laws from top to bottom, slew the stand-pate special interest groups, cleaned stultifying state regulations from the books, and—maybe, just maybe—found a way to bring public schools back from the dead.

The chairmen of the Senate and House education committees were a perfect team: Ratliff the engineer, Sadler the lawyer, both of them small-town East Texans with calm, logical demeanors and old-fashioned notions of public service who somehow rose to prominence in the Legislature without losing their idealism. Neither was beholden to the jealous factions—teachers, administrators, superintendents, and school boards—that stubbornly resist education reform. Both embraced Governor Bush’s desire to return power to the local level and make schools more accountable to parents. Though they came from different political parties, they cared more about policy than partisanship.

Before the session, Ratliff held hearings on reform proposals, letting all the groups have their say. Then he went back to Mount Pleasant and wrote a 1,100-page draft on his home computer. The document was not the usual hodgepodge of recommendations designed to appease particular interests (“He kinda ignored us all equally,” said one education lobbyist); rather, it represented his own philosophical approach to deregulation. He kept a few state requirements that he thought were important, such as the no-pass, no-play rule and the 22-to-1 student-teacher ratio, but provided for school vouchers and local choice of textbooks.

When Senate and House negotiators met to work out the final version of the bill, Ratliff set a new standard for putting educational considerations above personal interest when he opposed giving special education students the same diploma other students receive. Noting that his own grandson is a special education student, Ratliff said, “My grandson is a delightful kid, but the education system of Texas would be judged badly if in twelve years he is handed the same diploma as any other person. As much as it tears my heart because of who it is, that’s still the case.” Later he fashioned the crucial compromise that dropped vouchers from the final bill but kept a modified version of the 22-to-1 ratio for low-performing schools.

Sadler’s role in education reform went far beyond sponsoring the bill. Two years ago he prepared the way for change by helping pass a bill that repealed most of the state’s education laws. This session he fought not only for reforms but also for a teacher pay raise. When house budget writers initially made no provision for a pay hike, Sadler told the House, “I ask the question, When will we stand up and do what is right for education in this state…. For what group of children will we answer that question? For mine? For yours? For our grandchildren?” In the end, he won a $271 million raise for the state’s lowest-paid teachers.

He got off to a later start than Ratliff and incurred more resistance from his colleagues. Prodded by Speaker Laney to finish his committee’s deliberations and get a bill to the House floor, Sadler said that the issue was too important to rush. He conducted marathon meetings that ran well past midnight three days a week, met frequently with Bush, and ultimately produced a bill that went further toward embracing the governor’s view of deregulated home rule school districts than Ratliff’s did. Minority members protested vigorously that Sadler’s power-to-the-parents approach didn’t address problems in urban districts, where many families are fatherless. But Sadler—and Ratliff—had managed to convince the normally cautious Legislature that the uncertainty of change was preferable to the mediocrity of the status quo.

Respecting the Difference

Sylvester Turner

Democrat, Houston, 40. He was the voice of the loyal opposition, and he found a lot to oppose. Three of the four big issues in Governor Bush’s program—juvenile crime, welfare reform, and education reform—seemed to be aimed directly at minorities. Day after day, week after week, Turner stood before the House and waged his lonely fight, often in anguish but rarely in anger. He knew that he couldn’t change the outcome; the best he could hope for was to make people understand. “Until you have walked in the shoes of those who you’re trying to regulate,” he said during the welfare debate, “it makes it very difficult to try to tell other people how to do things better.”

Typically the House is not a place where opposition is welcome. Its culture is “go along to get along”; when members linger too long at the microphone, voices shout out “Vote! Vote!” to hurry the proceedings along. Yet whenever Turner took the floor, the buzz in the chamber died out and was replaced by the silence that signals respect. He put on a good show, punctuating his speech with sharp movements of his hands and index fingers, like a conductor wielding a baton to mark the beat of his own words. Here’s Turner on juvenile justice: “If the people in the system had the hearts of mothers and fathers, I would not be standing here.” On cutting welfare benefits: “Penalize the mother, penalize the irresponsible father, but do not penalize the children of the state of Texas.” On local control of education: “[It] provides enough boats to take some of the kids off the burning ship, but it leaves most of the kids on that ship that’s on fire.” And he reminded his listeners that he was one of them too, a participant in the deliberative process: “I know we differ, I respect the difference, but let me come here with my own experiences, my own background.”

Turner did manage to amend several of the bills he fought and passed an open-records bill, but opposition was his forte. His most memorable moment came during the House debate on education reform, when he predicted that unchecked local control could turn back the clock to the segregated schools of the fifties. “A hopeless generation is a dangerous one,” he warned. “And when their leaders lose hope, they lose hope, and when their leaders become frustrated, they become frustrated.” As he spoke, black and Hispanic members gathered around him in a show of unity. For two more days the debate over education continued, finally ending after midnight on a Sunday morning. A few hours later, Turner and two colleagues caught the early plane to Houston. “Will I see you in church, Syl?” asked one as they deplaned. “No,” said a weary Turner. “I’m going straight to Bedside Baptist.” He’d earned it.

The Worst

Life is Unfair

Gonzalo Barrientos

Democrat, Austin, 53. He didn’t want to be in the Senate this session, and he acted like it. He had bided his time for years, waiting to replace Jake Pickle in Congress, only to see destiny snatched from his grasp when Lloyd Doggett resigned from the Texas Supreme Court to seek the seat and got the backing Barrientos had been counting on. So he spent the session sulking and pouting, mulling on the unfairness of life and making the Senate pay for his disappointment. Among his grievances:

The education reform bill. When Senator Ratliff detailed how far he had gone to inform colleagues about his bill, Barrientos contradicted him. “I beg to differ with you just a little bit. I do not think that all of the members are sufficiently enlightened about the bill to perhaps feel comfortable voting on it,” he complained. Maybe he was unaware that there had been two special briefings for senators, since he didn’t attend them. Then he proceeded to offer a succession of doomed amendments. When Lieutenant Governor Bullock hinted that he gesture was pointless—all the amendments were being defeated by the same large margin—Barrientos again groused. “If the parliamentary process will allow me to close,” he sniped.

Gubernatorial appointments. Another blow: Barrientos had to step down as chairman of the Nominations Committee when Bullock decided that a Republican governor deserved to have a Republican head the committee that screens his appointees. A graceful loser he was not. Questioning Nolan Ryan, named by Bush to the Parks and Wildlife Commission, Barrientos asked, “Can you tell me one thing about why you think you’re qualified to serve on this board?” Then he asked Ryan to autograph a baseball. When billionaire Lee Bass, who was being reappointed to Parks and Wildlife, testified that the agency’s record of hiring minorities had improved by 3 percent during his tenure on the board, Barrientos broke in with a sarcastic “whoopee.” Once, in floor debate, he made so many references to the way he had run the committee that his successor, Teel Bivins of Amarillo, finally rebuked him publicly: “I’m the chairman of the committee now, Senator, not you.”

Austin bashing. Near the end of the session, Barrientos criticized his colleagues for passing a series of developer-backed bills that restricted Austin’s right to control suburban growth. Twice he filibustered into the late hours in a futile effort to sway his colleagues. The local media were duly impressed, but Capitol insiders were not. They knew that most senators would never have voted to meddle in the local affairs of a colleague for whom they had respect. That was the problem with Barrientos’ churlish behavior. The ability to function in the Senate depends entirely upon relationships, and Barrientos alienated senator after senator. He hurled down his microphone and turned his back when one tried to debate him. He asked the Department of Public Safety to investigate a nominee from another colleague’s district, without notifying the other senator first. In a conservative year, the Senate’s dwindling bloc of liberals needed all the help it could get. But Barrientos was too bitter to be of any use.

The Bad Old Days

Kim Brimer

Republican, Arlington, 50. The word that comes to mind is “shameless.” Kim Brimer is a throwback to the bad old days, when powerful legislators did as they pleased, oblivious to public policy and contemptuous of standards of behavior. He carries sleazy bills, engages in ruthless power plays, and plunges into controversy as if it were his favorite swimming hole.

No special interest legislation raised more of a stink this session than Brimer’s booze bills. The first was a bonanza for current package store owners, who would be insulated against further competition. The brainchild of industry lobbyists, the bill proposed to limit the number of liquor stores in every county in the state: a maximum of three in small counties and one for each 10,000 people in big counties. No new stores would have been allowed in the Houston, Dallas, and Austin areas; San Antonio, Fort Worth, and El Paso were close to the maximum. Brimer defended his measure as a way to stop the proliferation of liquor outlets in poor neighborhoods, but a concerned black legislator rejected the argument and an official with Mothers Against Drunk Driving described the motive for the bill as “strictly greed.” To speed the bill through the House, the committee that oversees liquor, which Brimer sits on, used a parliamentary ploy that is supposed to be reserved for noncontroversial items. Fortunately, the bill died in the Senate.

Brimer’s other liquor bill was even more odiferous. He embraced a Senate amendment that bestowed upon a handful of families the exclusive control of the distribution of liquor in Texas for all eternity: The bill gave each family a monopoly territory that could be passed on to future generations. That didn’t pass Governor Bush’s smell test, and he vetoed it.

Brimer never seemed to run out of bad ideas. Another of his measures gave police departments the right to conduct surveillance on and compile information about any juvenile who associates with people suspected of being in gangs, even if no criminal conduct is involved. Toby Goodman, a fellow Tarrant County Republican who is no law-and-order softie (he passed the governor’s juvenile justice reform bill), objected: “If you allow law enforcement agencies to compile information on people who have not committed crimes, every kid is at risk.” But Brimer prevailed.

Brimer’s involvement in workers’ compensation issues provided him yet another opportunity for mischief. He had been the chairman of a House-Senate oversight committee that was due to be replaced by a new board in September; the Senate, reasonably enough, said it was their turn to have the chairmanship, but Brimer wanted to keep the position for the house—meaning, presumably, himself. That battle lasted all session until Brimer capitulated on the final day. It was so unnecessary. Brimer has the skill to succeed by playing the game out in the open. But he would rather operate in the back alleys.

Bombing Out

Warren Chisum

Democrat, Pampa, 56. Last session Warren Chisum made the Ten Worst list because he was nothing more than a demagogue. This session he made it because he tried to be more than a demagogue—and failed miserably. He calls to mind the description of a turn-of-the-century English politician: “Dangerous as an enemy, untrustworthy as a friend, fatal as a colleague.”

The chairman of the Conservative Coalition got off to a bad start by flouting ethics laws against soliciting campaign contributions within thirty days of the start of a session: He held a caucus fundraiser on the eve of the session, contending that the ban applied only to individual legislators, not groups. When embarrassed House members tried to eliminate the loophole, Chisum fought them (unsuccessfully) and refused to reveal the coalition’s contributors.

He was his usual self on the House floor, zapping bills with amendments and points of order so often that members, adopting a ritual begun last session, whistled the sound of falling bombs whenever he approached the microphone. His amendment to prohibit the Texas Commission on the Arts from funding any project that includes sexually explicit displays was so broadly worded that Senate critics said it would require draping the statue of the Goddess of Liberty atop the Capitol. “Are you ready for what Representative Chisum is going to do to this bill?” Senator John Montford asked a colleague who was trying to pass an innocuous bill involving the arts. “There are not going to be many performing arts that escape his keen mind relative to reprehensible conduct.”

Chisum’s worst problems arose when he tried to get involved in substantive legislation. He didn’t do his homework, and he couldn’t be persuasive in debate. He tried to pass a controversial bill giving immunity from lawsuits to companies that voluntarily disclose violations of environmental laws. But when opponents started to ask hostile questions, Chisum couldn’t explain the bill; the best response he could offer was, “It’s not my intention to cover up any wrongdoers.” Fearing that certain defeat loomed, two other backers of the bill took over from Chisum as floor managers and passed it.

Many House members like Chisum, whose elfin stature and dry wit make him a sort of town character. But they don’t respect him. In the final hours of the session, Chisum went to the microphone with an innocent motion to suspend a procedural rule, making it easier for the House to clear its calendar. Instantly a long line of members, conservatives and liberals, Republicans and Democrats, formed at the back microphone to ask questions. Why do we need more time? Chisum couldn’t give a clear explanation. How many items are eligible for the calendar? Of course, he didn’t know. The motion failed by a huge margin. The message for Warren Chisum was clear: You can’t be a demagogue for 138 days and expect to be treated as a serious legislator on the 139th.

Honk! Honk!

Frank Corte

Republican, San Antonio, 35. Mercenary. Mendacious. Malicious. Petty. Meet Frank Corte, one of the more dismal products of democracy to reach the Legislature in many a year. Let’s take it from the top.

Mercenary. In a flagrant display of self-interest, Corte, who owns apartments, led a floor fight against a bill to provide deaf tenants with strobe-light fire alarms. The bill’s sponsor explained that she had reached an agreement with landlord groups for the tenant to provide the alarm and the landlord to pay for the wiring and maintenance. “I think you might be telling me this is one of those agreed-to bills. Is that what you’re trying to tell me?” Corte asked. She was. But he kept up the attack and the House killed the bill.

Mendacious. Along came another apartment bill, this one strengthening the rights of tenants with regard to their security deposits. When Corte led the fight against it too, the sponsor said, “Representative Corte, we have talked about this and I asked if you had any questions. You said you didn’t like it, and then as I recall, you said you wouldn’t work against it.”

Malicious. A delicate compromise had been reached on Governor Bush’s tort reform bill putting a strict limit on punitive damages—but Corte wanted to make it even more strict. Members were in a bind: If they voted against the amendment, they would look soft on tort reform. If they voted for it, they might wreck the deal. When the Republican point man for tort reform pointed out that his amendment breached the agreement everyone had worked all session on, Corte smirked, “If you’re gonna tell me the governor’s gonna veto this bill ‘cause this amendment goes on, that’s a choice he’s gonna have to make.” The point man said, “I’d appreciate it if you’d pull your amendment down.” Corte wouldn’t. A Democrat was more blunt: “I think it’s a little obnoxious for members to have to vote on this amendment.” Corte wouldn’t relent—but he lost, 116-27.

Petty. All session long, San Antonio legislators squabbled over a federal judge’s threat to regulate the pumping of water from the Edwards Aquifer if the state didn’t come up with a plan of its own. Just when the issue seemed resolved, Corte killed the bill with a point of order. Said Senator Jeff Wentworth, a fellow San Antonio Republican: “I think it was extremely shortsighted and petulant of Frank Corte… It wasn’t in the interest of anyone in Bexar County, San Antonio, or especially in the military bases for this bill to be defeated.”

Finally the House struck back. Unaware that one of his bills had reached the top of the calendar, Corte had to be summoned by the Speaker over the microphone. “Frank!” shouted a member. “Frank!” came another shout. Other members took up the chant: “Frank!” “Frank!” As the chorus gained new volunteers, the shouts became more nasal, until they began to sound like “Honk! Honk!” A goose: That’s about the nicest way to describe Frank Corte this session.

Dumb and Dumber

Michael Galloway and Drew Nixon

Michael Galloway—Republican, The Woodlands, 30. Drew Nixon—Republican, Carthage, 35. Was the hottest debate in the Senate this session over (a) tort reform, (b) concealed handguns, or (c) affirmative action? None of the above. The real question on everyone’s mind was, Which of the two freshman senators from East Texas is worse: Galloway, the political novice who upset Senate legend Carl Parker, or Nixon, whose campaign last fall was dogged by his 1993 arrest for illegally carrying a handgun in his car? No one expects first-year lawmakers to shine, but these two were dimmer than Jim Carrey.

Galloway made a name for himself even before the session started when he perused a lobbyist’s check at a fundraiser and said, “That’s a little light.” No sooner had the Senate started working than he committed the unpardonable sin of voting against a Republican colleague’s local bill. That earned him a heated lecture on senatorial courtesy, but to no avail; a few weeks later, he did it again.

No matter what the issue, he was utterly clueless. When an Environmental Protection Agency official testified before the committee about air pollution, Galloway asked, “What does it do to you? I mean, at what level do you die?” On another occasion, a colleague asked Galloway to explain one of his own amendments but mercifully withdrew the question after Galloway shuffled papers for so long that it was apparent he didn’t know the answer.

He had no more influence on the course of events in the Senate than a speck of dust in the path of a bowling ball. He passed only one bill of any significance—dismantling the Lamar University system and putting the school into a system with other regional colleges—and it was almost too much for him. He couldn’t answer questions in committee, even softballs such as whether Lamar had any programs that had been singled out for excellence. Advised to ask Lieutenant Governor Bullock for help in passing the bill, Galloway did so; meanwhile, he resisted Bullock’s overtures to vote for judicial reform. If it ever occurred to him that there might be a connection, he didn’t let on. Finally, Galloway proudly told Bullock that he had changed his mind about judicial reform after talking to Texas Supreme Court chief justice Tom Phillips. Great, said Bullock. Go see the chief justice when you want to get your Lamar bill passed. Says a fellow senator: “He’s not even coachable.”

Nixon’s problem was not ignorance; it was arrogance. He toyed with gubernatorial appointees as if they were Power Rangers. On one occasion he invoked senatorial privilege to block the confirmation of an appointment to the Trinity River Authority. Uh-oh. The unfortunate appointee was a constituent of House honcho Allen Hightower, who thought Nixon had told him that confirmation wasn’t a problem. Hightower is the wrong guy to offend, and he quickly gave Nixon a lesson in hardball. Only a contrite Nixon apology—and his approval of the nominee—saved his entire legislative program from certain death in the House. In another episode, Nixon, a certified public accountant, invited three IRS agents to a hearing at which he questioned three nominees to the Sabine River Authority at length about the agency’s expenses and accounting practices—and then didn’t object to their confirmation. Suffice it to say that other senators did not look kindly upon having the feds in the Capitol, where they just might get ideas about other things to investigate. And we don’t mean who’s dumb and who’s dumber.

Decline of the West

Mike Krusee

Republican, Round Rock, 36. He never smiles. Mike Krusee mopes around the House floor, certain that he is watching Western civilization collapse before his very eyes. He bears the weight of the world on his shoulders and blames the Democrats for putting it there. Krusee is the truest of the true believers, someone who believes that there are only two ways to look at any issue: his way and the wrong way.

In floor debate he can get so sharp and intense that the atmosphere of civility fails. Speaking in favor of a bill limiting Austin’s annexation powers (Krusee is one of the House’s most ardent Austin bashers), he was so vituperative in his attacks on the city’s officials that gasps and hisses were audible on the House floor. During the welfare reform debate, Krusee led the fight against a Democratic amendment that was acceptable to the bill’s Republican sponsor. “Mr. Krusee,” said the sponsor, “I respect you for your view, but let me also tell you that it’s a very harsh one and it does not make the state of Texas any better.”

Later in the debate Krusee offered an amendment to prohibit unwed teenage mothers age fifteen and younger from receiving any welfare benefits. “Illegitimacy is the single most important problem of our time,” he said. “It is more important than crime, more important than drugs, more important than poverty, more important than illiteracy or homelessness, because it drives everything else…. The family as we have known it throughout Western civilization has collapsed.” But then some Republican colleagues began whispering in his ear that his amendment would cause more abortions, and suddenly Krusee gave up rather than force Republicans to choose between abortion and welfare reform. “I couldn’t do that to the Republicans, the people I love,” he said in an interview. “If I could have done it to the Democrats, I gladly would.”

He looked more morose than ever, and for a moment it was easy to empathize with him: He had made an eloquent plea for a cause he considered to be of the utmost importance—and no one had listened to him. But moments later he demonstrated why no one listens to him: He tried to change the name of the Lone Star Card, which is used by welfare recipients, to the Government Assistance Card. Accused by an opponent of “just trying to stomp people,” Krusee said, “The lone star is the symbol of our state. It stands for independence and self-reliance. It doesn’t belong on a welfare card.”

Who cares? If Mike Krusee truly believes that he future of the country depends on preventing illegitimate births, then he should be turning heaven and earth to do something about it. He should be looking for any allies he can get, including Democrats. He should forget about purely symbolic gestures and concentrate on what’s important. If you want to be a fireman, you’ve got to know the difference between a campfire and a forest fire.

Bad Report Card

John Whitmire

Democrat, Dallas, 45. Every grade-school teacher knows the type: the little boy who would do so much better in class if he weren’t so impetuous and desperate for attention. That’s Senator John Whitmire. When he buckles down and studies, as he did on last session’s prison reform bill, he makes the honor roll. But when he disrupts the class and makes messes that others have to clean up, as he did this year, he ends up in the principal’s office.

And what a mess he made of his attack on the state’s program to comply with the federal Clean Air Act. Discovering from radio talk shows that the program—which would test auto emissions in Houston, Dallas, the Golden Triangle, and El Paso—was unpopular, Whitmire called for a ninety-day moratorium and pooh-poohed fears of losing federal funds or getting sued by the testing company, Tejas Testing Technology. But enough lawmakers were worried about litigation that the Legislature decided to lend Tejas $8.8 million until Whitmire came up with a better testing program. He couldn’t. He watched helplessly during a chaotic debate as senators exempted their districts from his bill and then voted to extend the moratorium to two years. “We’ve come full circle,” said an incredulous Lieutenant Governor Bullock. “We got nowhere fast.” Finally the Legislature tossed the ball to the governor; in the meantime, Texas faces the possibility of federal sanctions and Tejas has initiated legal action against the state for $150 million.

Another mess: Whitmire’s revisions of the new penal code, which he helped write in 1993. This session, his bill carried a whopping initial price tag of $600 million for housing more prisoners. When House Members balked at the cost, Whitmire pulled an adolescent stunt: He got a Republican colleague to let him distribute, on her stationary, a letter written by GOP state chairman Tom Pauken criticizing a key House member for holding up the bill. The charge turned out to be erroneous. Though the colleague issued a letter of apology, the House member was furious, and progress on the bill stalled until peacemakers intervened.

His problem is a fatal combination of ambition and rashness. His eagerness to grab a popular issue has inspired rumors that he is interested in running for attorney general or mayor of Houston. But he acts first and thinks later—if at all. As the session drew to a close, he did it again. As chairman of the Criminal Justice Committee, Whitmire had to pare the cost of a bill that had already been approved by his panel. Rather than go through the proper procedures, Whitmire took telephone proxies from his committee- a no-no in every parliamentary body that has ever existed. When a colleague questioned him about the tactic, Whitmire blew up. “I think you question the integrity of me and this body and all of us who operate this way,” he snapped. Send that kid back to the principal.

Oily Doyley

Doyle Willis

Democrat, Fort Worth, 86. The kind of legislator who could turn Pollyanna into a cynic. His idea of family values is using his position to give things of value to his own family.

In 1991 Willis got state licensing officials to double the number of chances potential nursing home administrators had to pass a qualifying test, from three to six. It seems that one of his daughters had flunked the test. In 1993 he sought a change in state pension laws that would allow him to shift his beneficiary from his wife, who no longer lives with him, to one of his daughters without getting his wife’s consent. The provision didn’t make it into the final bill, so Willis tried again this year. This time, he got caught. “Oh, that’s the Doyle Willis amendment,” the pension bill’s Senate sponsor confessed to a newspaper reporter. Following an embarrassing round of headlines that squelched the ploy, Willis got his wife to sign a consent form.

We’re not talking peanuts here: Willis was first elected to the Legislature in 1947, or maybe it was 1847, and is eligible for an annuity of more than $65,000 a year. It would be worth the money to be rid of him. In his heyday he was known as Oily Doyley for reasons that have long since been forgotten but are not difficult to imagine. When he made the first Ten Worst list, in 1973, we wrote, “One of the least competent legislators, he has fed at the public trough for most of his adult life.” He’s still feeding. One of Willis’ bills this session would have given a tax exemption to veterans who sell agricultural property that they have owned for more than twenty years. According to a fellow House member, Willis estimated that only forty or so veterans qualified for the break. One of them was—who else?—Oily Doyley.

Special Awards

Best Quip

Former senator Carl Parker of Port Arthur, a liberal Democratic stalwart who was defeated for reelection last fall, came back to the Capitol as a lobbyist. When a business lobbyist asked how he was faring, Parker said, “Great! All your friends are hiring me to protect them from all my friends.”

All-Star Team

With the former managing general partner of the Texas Rangers occupying the governor’s office, baseball metaphors were in vogue at the Capitol. So here are the awards for the legislative leadership team, which had its most cooperative session in many a year.

Rookie of the Year: George W. Bush. The governor passed his entire legislative program without a hitch, including his most controversial proposal, home rule for school districts. When the session began , no one—except possibly Bush himself—thought that a strong education reform bill had much of a chance, but he paved the way by forging personal relationships with numerous legislators. In the end, it passed with ease.

Manager of the Year: Bob Bullock. The lieutenant governor had to handle a difficult lineup of seventeen Democrats and fourteen Republicans. From opening day on, he drove the Senate to handle the big issues early, as if he had had a premonition of disaster. It came true on March 26, when his parliamentarian and close friend of nearly forty years, Bob Johnson, died from a heart attack. Johnson’s institutional knowledge and his advice to Bullock and senators alike made him irreplaceable. And yet Bullock’s control of the Senate remained unwavering, if sometimes heavy-handed (he interrupted a debate over whether to pay a multimillion-dollar court judgment to whistle-blower George Green by introducing Green, who was in the Senate gallery, and describing him as “a man who has been wronged by the State of Texas”). After midnight on the last night of the session, he frantically ran through the final calendar of bills at the speed of an old Federal Express commercial. His critics called him a control freak, but his single-mindedness guaranteed that the state’s business got done.

Strikeout Ace: Pete Laney. A more relaxed leader than Bullock, the populist Speaker of the House put his mark on the session despite its overwhelmingly pro-business tilt. Laney is a farmer from tiny Hale Center, north of Lubbock, and like most farmers, he has never looked kindly on big concentrations of economic power. It was no coincidence that any interest group fitting that description struck out in Laney’s House: big banks (they lost one key issue by a vote of 142-0 and another never came up for a vote), big insurance companies (they will have to lower their rates because of tort reform), and big utilities (they didn’t get the protection against competition that they sought).

Honorable Mention

At the top of the Honorable Mention list is Fannett Democrat Mark Stiles. He has a record worthy of a Ten Best legislator, but like last year’s Aggie football team, which was denied a Cotton Bowl bid because it was on probation, he is ineligible. Newspaper reports have questioned whether Stiles, the president of a cement company, has used his position to become a subcontractor on major state construction projects. The controversy caused him to cast a neutral “present” vote on the state budget.

Old Reliables

Allen Hightower, Democrat, Huntsville

Kenny Marchant, Republican, Coppell

Curtis Seidlits, Democrat, Sherman

Senator David Sibley, Republican, Waco

Steve Wolens, Democrat, Dallas

Career Years

Toby Goodman, Republican, Arlington

Todd Hunter, Democrat, Corpus Christi

Steve Ogden, Republican, Bryan

John Smithee, Republican, Amarillo

Dianne Delisi, Republican, Temple

Comers

Fred Bosse, Democrat, Houston

Robert Duncan, Republican, Lubbock

Scott Hochberg, Democrat, Houston

Senator Jerry Patterson, Republican, Pasadena

Best Nickname

Senate Democrats began referring to JANE NELSON, Republican, Flower Mound, as Calamity Jane, or just plain Calamity, after she repeatedly shot down efforts to reach a compromise on the sensitive issue of affirmative action.

Furniture

The term “furniture” first came into use around the Capitol to describe members who, by virtue of their indifference or ineffectiveness, were indistinguishable from their desks, chairs, and spittoons. It is now used casually and more generally to identify the most inconsequential members. Here is the unusually large furniture list for the Seventy-fourth Legislature.

New Furniture

Gary Elkins, Republican, Houston

Judy Hawley, Democrat, Portland

Barbara Rusling, Republican, Waco

Gilbert Serna, Democrat, El Paso

Burt Solomons, Republican, Carrollton

Dale Tillery, Democrat, Dallas

Used Furniture

Homer Dear, Democrat, Fort Worth

Joe Driver, Republican, Garland

Bob Glaze, Democrat, Gilmer

Roberto Gutierrez, Democrat, Mcallen

Jesse Jones, Democrat, Dallas

Senator Gregory Luna, Democrat, San Antonio

Huey Mccoulskey, Democrat, Richmond

Jim Pitts, Republican, Waxahachie

Buddy West, Republican, Odessa

Antique Furniture

Charles Finnell, Democrat, Holliday

Sam Hudson, Democrat, Dallas

Senator Don Henderson, Republican, Houston

Best Additions to the Legislative Lexicon

The legislature has a language all its own. Some terms, such as “flake” (to renege on a promise to support or oppose a bill), have been in use for many years. Others, such as “lobster” (a lobbyist), are newer. Here are the latest expressions to come out of the Capitol.

BELLFARE: In general, a telecommunications bill regarded by opponents as excessively generous to Southwestern Bell. In particular, the one that passed this session.

HUBCAP: An attempt to block an affirmative-action provision for HUBs (historically underutilized businesses) that gives minority-owned firms a share of state contracts.

RIG COUNT: The number of TV camera tripods in the Capitol on a given day. A high rig count is a sure sign that a major issue is about to be debated.

Dishonorable Mention

This year only nine legislators made the Worst list. The final slot remains vacant because the only other lawmakers who committed blunders bad enough to land them in the bottom ten had more credits to their name than demerits: Ron Wilson, Democrat, Houston, and Judith Zaffirini, Democrat, Laredo.

Wilson played the race card as if it were the ace of trumps. In one of the session’s pivotal moments, he donned Ku Klux Klan regalia to attend Republican senator David Sibley’s press conference about his proposal to eliminate affirmative-action programs. Said Wilson: “I was rummaging around in Senator Sibley’s closet and dredged this up.” His antics—and their message that questioning affirmative action is illegitimate and racist—destroyed the atmosphere of goodwill that is essential to finding common ground through the legislative process. Republican opposition hardened. Both the House and the Senate fought over affirmative action for the rest of the session, with the result that blacks were the big losers. Wilson’s actions caused his side to cede any claim to the moral high ground. Yet, when he got off the subject of race, he was a powerful and unpredictable force; he sponsored the concealed-weapons bill, going against the grain of black urban Democrats, and he was the member who best knew the arcane House rules and how to use them to get what he wanted.

Zaffirini is the most effective senator South Texas has ever had—so effective, in fact, that she drives her colleagues nuts with her schemes to grab goodies for her impoverished district. She usually succeeds, because she is incredibly relentless and hardworking (she arrives at the Capitol before five in the morning), but this year she tried to grab too much. Without advance warning, she introduced a bill to shift Texas A&M International University in Laredo to the University of Texas system. The bill zipped through the Senate, but the Aggies declared war and stalled it to death in the House. The rift her bill opened between the state’s two big universities, which usually try to maintain a united political front, still hasn’t healed. Meanwhile, state leaders have decided that before any future legislative meddling with colleges can take effect, it must be approved by the higher education coordinating board. Zaffirini’s overreaching canceled out an otherwise excellent session, in which she passed major bills overhauling the welfare and Medicaid systems.