For 140 days the seventy-seventh legislature searched for its personality without finding it. This was a budget-trimming session in which money was tight. No, it was a free-spending session in which state expenditures increased by $14 billion. This was a session that would be dominated by redistricting. No, the Legislature didn’t even pass a redistricting bill. This was a session when legislators took off a week to go to Washington to celebrate the inauguration of fellow Texan and former governor George W. Bush. But it was also a session when lawmakers passed bills to repair the damage to the state’s reputation incurred during Bush’s tenure and presidential campaign.

Republicans went to the inauguration elated and came home deflated, almost with a sense of “Daddy’s gone. What do we do now?” New governor Rick Perry had few suggestions. Both he and Lieutenant Governor Bill Ratliff, having filled vacancies, were unelected, and neither had a mandate to lead. With no one imposing an agenda on the Legislature, the lawmakers went about their routine business with no sense of urgency. The only piece of legislation that absolutely had to pass was the budget, and the only parts of the budget that posed serious problems were Medicaid and teacher health insurance. Not surprisingly, the lawmakers who figured out how to make these programs work without rupturing the budget made the Best list.

The one thing that could have ruined the session—partisan warfare—never came to pass. The hate crimes bill could have been the Fort Sumter that plunged the world of the Capitol into civil war, but in this torpid session, the will to fight just wasn’t strong enough to generate action. Anyway, the war is coming; it will be waged in the 2002 elections and in the 2003 session, but for now, everybody was content to run away and live to fight another day.

So let’s call it the antebellum session. We followed it on the floor and in committee, day after day and for a few late nights. We found our heroes in those who looked for common ground in a divisive time, and our villains in those who failed to do likewise. And as always, we found some folks who are in immediate need of reconstruction.

THE BEST

Garnet Coleman

Knowledge is power. Seldom has the truth of this old saw been demonstrated more convincingly than by Garnet Coleman this session. He came to Austin in January wearing a Kick Me sign, which he hung around his own neck by way of campaigning vigorously against George W. Bush last fall. House Republicans obliged by trying to gut two of his bills as soon as they got the chance. But when crunch time came, and the problem of how to pay for Medicaid looked as if it might wreck the budget and with it the entire session, Medicaid expert Coleman proved to be indispensable.

Medicaid, which provides health care to children in poor households, is a mind-clogging maze of acronyms, waivers, and arcane regulations. But the political problem was simple. On the one hand, Texas needed to cover more than 600,000 eligible kids who were not participating in the program—mainly because of an arduous application process that seemed perversely designed to discourage participation (thereby saving money). On the other, covering them cost money the state did not have. The job of solving the dilemma fell to an informal working group, of which Coleman was a co-chair, appointed by the House and Senate budget chairmen. His job: find the money to cover everybody. And he did it, in part with a plan to get $9 from the feds for every $1 Texas puts up. You don’t want to know the details, and we’re not sure we can explain them; suffice it to say that when Coleman finished fiddling with the equation, the numbers balanced.

His performance is all the more praiseworthy because he had to deal not only with his opponents in the legislative process but also with his own demons. Coleman has a history of depression, and he fought to hold himself together through weeks of little sleep, bad food, and intense pressure. His final test was negotiating with Republican Arlene Wohlgemuth over her proposals to hold down costs.The whole Capitol, it seemed, was holding its breath. Late one night they emerged from a conference room into a nearly deserted House chamber, grinning and hugging, and the moment they appeared, you knew the session was saved.

Robert Duncan

Like all rookie senators, no matter how great their potential, Robert Duncan had to spend time on the bench in 1997 and 1999 before he could get in the game. His apprenticeship over, Duncan stepped up to the plate this session and hit the ball out of the park. With former Senate leaders Bill Ratliff and David Sibley no longer in the starting lineup—Ratliff because his duties changed when he won the race for lieutenant governor and Sibley because his morale plummeted when he lost it—Duncan became the Senate’s cleanup hitter.

You name the issue and chances are the slender, sandy-haired lawyer was involved in it: His bills addressed nuclear-waste disposal, workers’ compensation reform, Permanent School Fund investment procedures, the selection method for appellate judges (he wanted to change it from election to appointment), DNA testing of inmates in Texas prisons, and on and on. He took on the Bubba lobby by passing a bill to prohibit hauling teens around in the back of pickups. He tried to save the state’s nursing home industry by reducing lawsuit costs and even won passage of a politically risky fee that would have drawn more federal dollars for Texas homes—only to be embarrassed when Governor Perry belatedly threatened to veto the bill if the fee wasn’t removed.

It’s impossible to go to bat that often without striking out occasionally. Duncan found himself in the center of a firestorm when, at Perry’s request, he temporarily withdrew his support for the hate crimes bill, forcing a delay in its consideration. He had the thankless task of trying to find a middle ground between anti-nuke activists and business interests on the question of where to store low-level nuclear waste (his efforts died in the House). But his batting average was high, and he had some “Plays of the Day,” as when his incisive questioning exposed the flaws of an amendment that would have gutted the hate crimes bill. No one would dispute his place on this season’s all-star team.

Jim Dunnam

He’s a throwback to the old days, when success in the House rested on talent rather than title and you could do what you were big enough to do. Though he lacked a chairmanship or even a seat on a powerful committee, Jim Dunnam was big enough to pass two of the session’s biggest and best bills: charter-school reform and tougher restrictions on open containers of alcohol in cars. If the session were a video game, he would be the lone gladiator in light armor who successfully fends off the swords and maces of his menacing adversaries. Here comes Governor Perry, bent on committing mayhem against regulations on charter schools. Splat! There he goes, head over heels into the wall.

It took all of Dunnam’s skill to keep the open-container bill from blowing up like . . . well, a warm can of beer. Half of the House thought the bill was too tough; the other half thought it was too lenient. Rather than argue the point—a tactic that has proved fatal in previous sessions—he refocused the debate on the $43 million in federal highway construction funds that Texas had already lost and the $43 million more it would lose if the bill died or was weakened. Sticking to his theme of not letting Washington take away our money, Dunnam pointed to the high ceiling of the House chamber, with its handsome Lone Star chandeliers and lettering. “Look at the lights up there,” he implored his colleagues. “What does it say? It says ‘Texas.'” Not for the first time did parochialism prove effective in the Texas House.

The bill to reform state-funded but largely unregulated charter schools proved to be an even tougher fight. Dunnam wanted to prevent misuse of public monies and place a moratorium on new charters until the problems are corrected; Perry, a strong backer of the experimental schools, opposed a moratorium and urged additional study of their problems. Dunnam defeated a Perry-backed attack in the House, then negotiated a compromise with the Senate that addresses the misuse of state funds and places a ceiling, rather than a moratorium, on the creation of new charter schools. Perry may still get the last “splat!” by vetoing the bill, but Dunnam has proved that he can play the game.

Rodney Ellis

On an April trip to the white house, Rodney Ellis stood next to President Bush and waved at tourists from the Truman Balcony. Always the wiseacre, Ellis quipped, “They probably think I’m Colin Powell.” Bush, who is famous for bestowing nicknames, promptly dubbed him “the General.” The new moniker fit Ellis’ role back in Austin, where he commanded the troops in charge of drawing up the state budget as the chair of the Senate Finance Committee.

The unexpected elevation of Ellis to finance chair by GOP lieutenant governor Bill Ratliff proved to be one of the session’s defining moments. It assured that social services wouldn’t get short shrift and greatly increased the chances that the hate crimes bill, Ellis’ top priority apart from the budget, would pass. He handled the budget skirmishes like a seasoned combat veteran who had trained for this battle all his life. He wanted a teacher health insurance program, more funding for poor children’s health care and for the University of Houston, and more college grants for economically disadvantaged students. He got them all.

He was successful because everybody likes him. He works across party lines as well as anybody in the Senate; indeed, he won a struggle with the House for more Medicaid funding with the help of two Republicans. Most of the time he is charming, funny, flattering, and relaxed, but he can also be blunt, dead serious, critical, and relentless. When his first attempt to pass the hate crimes bill failed, he feigned indifference. “Moi? Do I look like a guy who has been tripped up? Do I seem angry?” he asked reporters. But when Governor Perry intervened to stop a vote on hate crimes, Ellis fired his heavy artillery, accusing his opponents of being “homophobics,” later saying, “If I offended somebody by my rhetoric a bit yesterday, tough. I meant it.” Under pressure, Perry signed the bill.

It’s no secret that Ellis has grown wealthy as a bond consultant while in office. But he is also the rare lawmaker who does good deeds with little publicity. He prevailed upon Continental, Southwest, and Delta airlines to provide free tickets to Austin so minority students could visit the University of Texas campus, and he runs an internship program for young people who are interested in politics. With Ratliff not returning as lieutenant governor and Republicans expected to increase their majority in the Senate, Ellis is not likely to remain as finance chair. At least when he got his chance to lead, the result was mission accomplished. Colin Powell, eat your heart out.

Juan Hinojosa

If the competition for the ten best list had been a horse race, nobody would have bet on Juan Hinojosa. He was carrying too much weight: a package of criminal-defense reforms, many of which were anathema to district attorneys and victims-rights groups, not to mention the lock-’em-up-and-throw-away-the-key types in the Legislature. To get his bills out of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, which he chairs, he faced a series of obstacles—including four law-and-order Republicans, among them an ex-sheriff and an ex-cop.

This last vulnerability Hinojosa turned into a strength; he joined the Republicans to his cause. He first came to the Legislature in 1981, back when it didn’t matter whether you had an R or a D after your name; left in 1991 to run for the Senate (he was defeated in the Democratic primary by Eddie Lucio, Jr.); then returned in 1997 to find the House a different place, with far less camaraderie and far more emphasis on partisan divisions. But Hinojosa still operates in the old style. This session he forged a relationship with former Travis County sheriff Terry Keel, who is the most credible authority in the House on how law enforcement really works. (“A great chairman” is Keel’s description of Hinojosa.) It was an amazing sight to see conservative Republicans asking friendly questions of Hinojosa during floor debate on his bills.

Here’s the laundry list of what he passed: a plan to provide indigent defendants with competent counsel; a DNA-testing procedure for inmates to attempt to establish their innocence; a ban on executing the mentally retarded (which faces a potential veto by Governor Perry); a requirement for corroborative evidence for drug busts, assuring that a much-criticized undercover operation in the Panhandle town of Tulia will not be repeated; and a prohibition of racial profiling by peace officers. He lost a few fights—notably, an attempt to provide a life sentence without parole as an alternative to capital punishment—but who would have ever guessed how often he would finish in the winner’s circle?

Bill Ratliff

Triumph and tragedy: the churchillian title sums up the session of Bill Ratliff, which began with his selection as lieutenant governor by his colleagues and ended with his decision not to seek election to a full term in 2002. The triumph was his own; the tragedy was Texas’.

For twelve years Ratliff has been an unwavering North Star in a political universe in serious need of guidance, moral and otherwise. But it was that very quality that led him to conclude that he could not bring himself to do the things that are necessary to run and win a statewide race. The job of lieutenant governor required Ratliff to balance responsibility with ambition for the first time. In the past his constituents in the northeast corner of Texas were happy to send him to Austin with no strings attached, trusting him to use his engineer’s skills to fashion sound public policy. In his new post ambition could have tempted him to use his prestige to jump-start a reelection campaign that likely would have cost him more than $10 million. Instead, Lieutenant Governor Ratliff turned out to look and sound a lot like Senator Ratliff. He mentored younger members, restored calm in tense moments, and mediated disputes, usually siding with the powerless against the powerful (for example, far-flung University of Texas campuses against UT-Austin).

He cast fewer than ten votes, supporting increased penalties for hate crimes, a ban on racial profiling by the police, approval of the state budget, and the creation of a teacher health insurance plan. But his fairness and scruples, so valuable inside the Capitol, did not play well with influential Republicans outside it. Ratliff once described himself as “51 percent Republican”; they wanted 100 percent. He was committed to an evenhanded Senate redistricting process; they wanted the most partisan plan possible. He wanted the hate crimes bill to pass; they wanted it to fail. And they blamed him for the eight-year-old Robin Hood school-finance plan that he helped pass at a time when the alternative was having the Texas Supreme Court close the schools. He is the kind of officeholder Texas needs, but he is also the kind that partisan politics does not produce. His withdrawal leaves a huge void—as if, suddenly, a black hole appeared where there once was a guiding star.

Paul Sadler

Session after session, speaker Pete Laney assigns Paul Sadler the responsibility of passing the most important, most demanding, most difficult issue on the Legislature’s agenda. And session after session, Sadler cruises to a successful completion of his task: overhauling the state’s education laws, raising teachers’ salaries while cutting school property taxes, and devising a farsighted tax-reform plan that, though it died in the Senate, continues to simmer on the back burners of public policy. This year’s mission: state-funded teacher health insurance.

“Around the first of April, I had serious doubts that we could do this,” Sadler reflected late in the session, when success was assured. “It looks so easy now, but we were befuddled. At a meeting of the House committee chairmen, I told them that this was maybe an issue we couldn’t simply solve.” The problem was finding a single plan for the state’s thousand-plus school districts that didn’t break the budget. The answer, Sadler finally decided, was not to look for a one-size-fits-all solution. He created a basic insurance program that is mandatory for small districts (those with fewer than five hundred employees) and optional for the rest; the districts and the state will share the cost for now, with the local share increasing to 100 percent after six years. But he couldn’t ignore the big school districts, who already offered good insurance benefits but had the political clout to kill the deal if they didn’t get something. So he provided for every teacher in the state to receive $1,000 to upgrade his or her health insurance—or, if a teacher chose, as additional compensation. A grateful House passed the once-controversial bill by the remarkable vote of 146-0. Once again Sadler had proved that if necessary, he could thread a needle with his toes.

This was a session, however, in which Sadler needed two miracles, and one was beyond his power to produce. In February his ten-year-old son was severely injured in an automobile accident. Doctors were not sure whether he would ever walk or talk again. Sadler left Austin for five weeks and did not return until his son began to show signs of improvement. On the last weekend of the session, Sadler strolled through the House, saying good-bye to colleagues and accepting their congratulations on two fronts: for the final passage of his bill and for the recovery of his son.

Senfronia Thompson

If you have a fenced goat, a fenced mule, a fenced chicken, a fenced hog, they are protected. If you happen to hurt those animals that are fenced in, you’re gonna get a chance to go to the state jail, get a state jail felony against you for that. . . . We have a chance, just like we protect the pigs and the goats, to protect human beings. And that’s what I am asking you to do when I ask you to vote for this hate crimes bill.” With that speech, Senfronia Thompson started the session’s most controversial bill on its way to passage. But she belongs in the top tier of legislators not simply because she passed hate crimes; rather, she was able to pass the hate crimes bill because she is in the top tier of legislators.

Thompson’s speech reveals why she is regarded as one of the best bill passers in the House. Instead of making moral appeals to her colleagues, she says, in effect, “You can vote for this; it’s not such a big deal.” And there’s always a little wry humor attached. When Republicans started asking questions about her bill to raise the state’s $3.35-an-hour minimum wage, she barked, “Let the little dogs eat”—a twist on the old adage “Let the big dog eat,” meaning that it is futile to fight the rich and powerful. Her bill requiring insurance companies to cover women’s contraceptives, just as they cover Viagra, would end “redlining in the bedroom.” (Like hate crimes, the minimum wage and contraceptives bills passed.) She delights in playing on House resentment of the Senate. Complaining about changes the upper chamber made to another of her bills, she told her colleagues, “We sent the Senate a doughnut, and they sent us back the hole.”

Thompson and Speaker Pete Laney are the last active members of the 71-strong House freshman class of 1973. They are about as different as two members can be—a white male farmer from the High Plains and an African American female urbanite—and yet in one essential way they are the same: They notice everything, they forget nothing, and they almost always get what they want.

Arlene Wohlgemuth

Dear Arlene,

You don’t mind if we call you by your first name, do you? Everybody else around the Capitol does. You could be the title of a C&W song: “Ara-lene, Ara-lene/Toughest gal I ever seen.” We’re writing to warn you that we’re fixing to ruin your reputation: We’re putting you on the Ten Best list. The Shiites and the Black Helicopter Caucus and the other true believers on the right wing of the Republican party in the House, who look to you as their leader, may begin to have second thoughts.

Sorry about that, but we just can’t leave you off. You had a great session in the toughest job there is—leader of the opposition—and your performance was masterful. You were always philosophical and never personal, never questioning the motives of others nor providing cause for others to question yours. You were the most articulate spokesperson for conservative principles (fiscal restraint, individual responsibility) that the House has seen since Ray Hutchison in the mid-seventies. By advocating things that government ought to do—including protect the rights of mobile home owners, come to the rescue of financially troubled nursing homes, and require insurers to cover birth control prescriptions for women, as they do Viagra for men—you paved the way for the time, not far distant, when Republicans will take up the burden of running the House. Best of all, you didn’t try to kill the important bill that expanded Medicaid services, even though you warned that it could sink the state budget in future years, but instead negotiated a compromise to contain costs and supported it in floor debate. That’s leadership.

There will be folks on the left who won’t like seeing you on the Best list either. They haven’t forgotten—who could?—the Memorial Day Massacre, four years ago, when the Democrats stalled an abortion bill late in the session and you retaliated by killing an entire calendar of bills. “The worst of the worst” we called you that year. But we put that memory to rest when, at 2:18 a.m. on the last night for passing House-originated legislation, you moved to resurrect a Democratic colleague’s bill that Republicans had killed earlier. Congratulations on completing rehab!

Judith Zaffirini

In the midst of heated negotiations with house members over the state budget, Senate Finance chairman Rodney Ellis received an unexpected package from his colleague, Judith Zaffirini. Though she sent no note, the gift conveyed an unmistakable message to Ellis to stand his ground on the Senate’s priorities. The box’s contents? A pair of brass balls.

Never, never underestimate Zaffirini, or Lady Z, as she is called by her colleagues with . . . affection? No, it’s more of a grudging respect. After all, this is a woman who, when asked to reach an agreement with two colleagues on a South Texas redistricting plan, rose to announce the place and time—in her office, at five in the morning. No problem for Zaffirini, who gets there each morning at four.

Nor does anyone question whether she knows her stuff. When it came time to debate a complete overhaul of Medicaid, Zaffirini took about five minutes of the Senate’s time to explain it and pass it. No one had any inclination to get in the way. Having spent her fourteen years in the Senate mastering Medicaid—the minutiae of court orders, federal regulations, and state budgeting—Zaffirini had won the total confidence of her colleagues.

She deserves great credit for generously increasing state spending on poor children’s health care, no easy feat in a tight-money session. She convinced the two Republicans on the Senate’s negotiating team that she had wrung the most care out of the available dollars and wore down House leaders with her inimitable relentlessness. Crisp and businesslike, she displays a grating sense of self-importance that should limit her ability to succeed, except that her colleagues know that no one works harder or shoots straighter. In mid-May it was announced that she had cast her 25,000th consecutive vote in the Senate—an unmatched feat, mainly because no one else cares about missing a vote now and then. But Lady Z cares about everything, which is why her colleagues gave her a standing ovation.

Honorable Mention

Speaker Pete Laney (Democrat, Hale Center) tops the list. His coalition of mainstream Republicans, rural Democrats, and minorities bent a bit under the pressure of partisan and ideological differences, but it still held together, perhaps for the last time. His five terms as Speaker have been remarkable for their fairness and their independence of the lobby, notwithstanding the complaints of a handful of disaffected Republicans who have no idea how benign Laney is compared to the Speakers of old.

Fred Bosse (Democrat, Houston) is the best member who has never made the Best list. Quiet and unassuming, he handles big projects such as the oversight of state agencies in the Sunset process without a misstep.

Kim Brimer (Republican, Fort Worth) passed a major economic-development bill offering school property-tax breaks as an incentive for companies to move to Texas. He even won over the education community, which usually looks askance at tax breaks.

Judy Hawley (Democrat, Portland) served as the chair of the rural caucus and quietly orchestrated the passage of a package of bills to help rural Texas.

Senator Steve Ogden (Republican, College Station) saw the big picture on hate crimes and was the first Senate Republican to support the bill. He also sees the little picture, as one of the few senators who pay attention to the details of legislation.

Senator Royce West (Democrat, Dallas) has a keen, practical understanding of criminal-justice issues. A former prosecutor, he has credibility with both sides on issues like his bill prohibiting racial profiling.

SPECIAL AWARD

Tomb of the Unknown

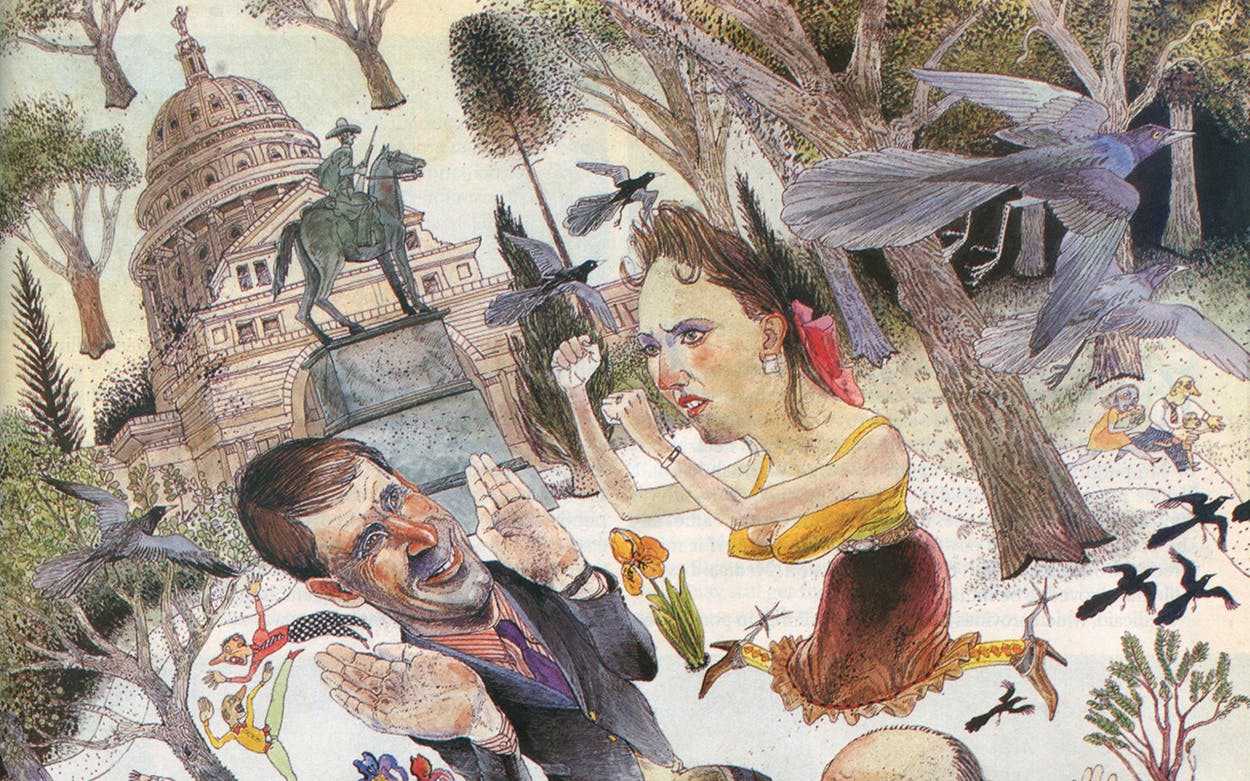

One of the most startling developments of the session was the failure of three of the Legislature’s all-time best members to perform up to their usual standard. But sometimes even the most valiant fighters cannot achieve their objectives. Sometimes even veteran warriors cannot escape hostile fire. The Tomb of the Unknown commemorates the anonymous legislative hero who, after many years of combat, fell from the heights. It could be Democrat Rob Junell of San Angelo, the longtime chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, who for once was unable to dominate the budget-writing process and had to yield to the Senate. It could be Democrat Steve Wolens of Dallas, the best debater in the House, who tried to defend the indefensible (utility company profits) and was outdebated by Democrat Sylvester Turner of Houston. It could be Republican senator David Sibley (above) of Waco, who, after losing the race for lieutenant governor, spent the first half of the session nursing his wounds, and then, when he returned to action, did so via the low road of partisan politics instead of the high road of public policy. We honor them for past deeds and hope for better things ahead.

THE WORST

John Carona

“You arrogant son of a bitch!” the session’s most memorable temper tantrum belonged to diminutive John Carona, who marched across the Senate floor in high dudgeon to confront Royce West, a fellow Dallas senator and a former UT-Arlington football player who looks to be about twice Carona’s size. Carona wagged a finger at West, West wagged back, and they exchanged warnings: “Don’t poke me!” “Back off! Back off!” A quick-thinking colleague hustled Carona off the floor so tempers could cool, but moments later Carona was back in West’s face again, fuming like a two-year-old who had escaped from time-out. Fearing, perhaps, for Carona’s life, Lieutenant Governor Ratliff intervened from the podium: “Senator Carona, could you please return to the other side of the aisle?” Just what caused the outburst of passion and anger? A dispute over an emotional public policy issue, like the death penalty or hate crimes? No, Carona was shaking with rage because he wanted to delay a proposed consumer-protection bill for a day so he could check with “industry representatives,” and West had offered only a thirty-minute respite.

Poor Carona: A once-promising senator has turned into a tool of the “industry representatives.” It’s not that he doesn’t work hard, it’s whom he works hard for: loan sharks and apartment-management firms (he used to own one). A consumer group called a package of Carona bills “the unlucky seven” and charged that they would cost Texans hundreds of millions of dollars. Carona proposed fees that amounted to interest rates ranging as high as 780 percent on payday loans; he fought, unsuccessfully, against state regulation of sale-leaseback transactions (in which the borrower typically pays $33 in fees per $100 borrowed on personal property, such as his own TV set); he tried to increase the fee for automobile title documents from $50 to $75 but was thwarted by a Governor Perry veto; and he attempted to allow landlords and property-management companies to sell renter’s insurance without state supervision of rates (the House killed the bill). If he had carried any more dirty water for lobbyists, he would have needed a permit from the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission.

Gary Elkins

In the legislative pond, Gary Elkins is a minnow. he feeds in the shallows, far from the dangerous waters of floor debate and important bills. He’s such a small fish that he escaped the Worst list in 1999 with a onetime catch-and-release exemption—even though no less than the Wall Street Journal had documented his efforts to help the small-loan industry, in which he makes his living (“Legislator’s Slim Agenda Mirrors His Private Interests”). So what does Elkins do this session? He swallows the hook again. Exemption expired.

Elkins’ livelihood is the controversial sale-leaseback business, in which customers, usually low-income, get cash for a household item, which they retain, and pay stiff regular fees until they can repurchase it. The industry claims that these transactions are leases, not loans, and that the fees are not interest payments, which would be subject to regulation. The attorney general’s office has sued Elkins’ company (unsuccessfully), and the Legislature, after several previous attempts, finally gave state regulators authority over the industry this year—but not without some unseemly shenanigans by Elkins. After the chairman of the House Business and Industry Committee, on which Elkins sits, introduced a bill declaring that sale-leaseback transactions are not loans, a lawyer for Elkins’ company testified in favor of the bill—but neither he nor Elkins disclosed the connection. Later, Elkins’ name surfaced again involving a bill backed by the payday-loan industry, a competitor of Elkins’ sale-leaseback industry. A Nevada company with links to Elkins (but no other apparent Texas concerns) had hired a lobbyist to fight the payday-loan bill. Referring to Elkins, an ethics advocate for Common Cause told the Austin American-Statesman, “If I were a member, any bill [he] had would be suspect to me.”

Elkins’ involvement in the issue is not illegal but does create the appearance of self-dealing. It gets in the papers and it lowers public confidence in the Legislature. Perhaps he could be forgiven if he made any noticeable contribution to the public weal, but no. He filed ten bills this session and passed one, making it legal to stop, stand, or park your vehicle in your own driveway in a manner that blocks a sidewalk. If only he had quit while he was ahead.

Mario Gallegos

A retired firefighter who threw gasoline on every combustible issue, Mario Gallegos confused ranting with representing. Content to let other senators do the real work, the voluble Gallegos contributed hot-tempered speeches when cool reason was needed. It seemed nothing could escape the racist tag: a traffic-safety bill banning teens from riding in the bed of a pickup (forget about saving lives; all Gallegos cared about was whether the police would have an excuse to stop Hispanic drivers); a bill limiting teens from late-night driving unless an adult is in the car (ditto); a bill requiring high school students to take the the college-bound curriculum if they planned to seek the automatic college admission awarded to top 10 percenters (obviously a trick to keep minorities out of college); even a proposal to move back the birth date for entering kindergartners (somehow, in Gallegos’ mind, an idea that would affect minority kids more than other kids). Some lawmakers always seem to have an ace up their sleeve; with Gallegos, it’s an entire pack of race cards.

His indifference to the legislative process was highlighted the day two senators, Democrat Royce West and Republican Robert Duncan, offered a carefully negotiated compromise on a bill to ban racial profiling, the practice of police officers making traffic stops based on race. When Duncan offered an amendment that won badly needed Republican support, Gallegos petulantly declared, “I don’t like your amendment.” How helpful. Thanks for letting us know how to make it better. Meanwhile, in the real world of problem-solving rather than just griping, Texas police departments will soon begin installing video equipment that will shed light on the nefarious practice and, hopefully, reduce it, thanks to West and Duncan’s hard work.

At least he could be counted on for comic relief—what Republican observers took to calling “Mario moments.” When the GOP’s David Sibley unveiled a redistricting map with new Senate boundary lines, Gallegos mentioned his own previous experience as a co-chair of the redistricting committee. In other words, he’s a guy who knows what’s going on. Then he asked Sibley if his plan complied with court rulings, “you know, Miranda rules.”

Yes, Senator Gallegos, you have the right to remain silent—and everyone fervently wishes you would.

Domingo Garcia

Domingo Garcia is a one-man leper colony. Nobody wants to be around him. What’s worse, the disease is self-inflicted. He set out to make himself the most despised member of the House, and it is about the only thing of note he has accomplished in his three terms.

To achieve absolute-zero status, you have to do something really special. Garcia was up to the challenge. In the spring of 2000 he set out to end the careers of four of his Democratic colleagues from Dallas and one from Fort Worth. He sought Hispanic opponents in the Democratic primary for Steve Wolens, Dale Tillery, Harryette Ehrhardt, and Lon Burnam, all of whom are white, and Terri Hodge, who is African American. None of Garcia’s agents were successful, but it didn’t matter: He had violated an ancient legislative taboo against actively seeking the defeat of one’s colleagues. The taboo exists for a good reason, which is that the legislative process cannot function without underlying goodwill and civility, and nothing destroys goodwill and civility faster than trying to end someone’s career.

The contempt for Garcia erupted for all to see during the debate over the ill-fated campaign-finance bill. He offered an amendment to impose a $500 fine on candidates who published or broadcast false information about an opponent. Uh-oh. Up came Wolens to the microphone with a question: “Can I make your amendment retroactive fifteen years, to the last time you ran against me?” Uh-oh again. Up came Hodge: “Are you saying that if I put on my campaign literature that you are a great guy and an outstanding representative that I could be charged a five-hundred-dollar fine?”

The irony is that Garcia, who apparently believes that Hispanics ought to represent Hispanics, cannot effectively represent his constituents. He wants a law school and a pharmacy school for South Dallas; he wants state universities to de-emphasize standardized test scores in admitting students; he wants the state’s electoral votes in presidential elections to be awarded by congressional district instead of winner-take-all. But he is such a marked man that he has no hope of getting anything done; indeed, he acknowledged to the Dallas Morning News that he had to farm out several of his bills to other legislators. And he has no one to blame but himself.

Rick Green

I do not like thee, Mr. Green

Exactly why I cannot ween.

But this I say, although it’s mean:

I do not like thee, Mr. Green.

Something about Rick Green just drives his house colleagues nuts. Maybe it’s things like his bill to let parents opt out of required immunizations for their children (currently allowed only for religious reasons). Maybe it’s things like the way he introduced his bill in committee: “If you had told me a year ago I would spend this much time dealing with shots, I would have assumed it was a gun bill.” Maybe it’s things like his argument for his bill, that three times as many kids are injured by shots as have gotten the disease the shot is intended to prevent. (Could it be that immunizations are the reason so few children get the disease?)

Still, one bad bill and an annoying style does not a Worst legislator make. No, Green had to go out and earn his notoriety. No problem. He spent the session embroiled in ethical pratfalls. First he sponsored a fundraiser for the Torch of Freedom Foundation, which he founded, and sold tickets to lobbyists; solicitations for charitable foundations do not violate prohibitions against fundraising during a session—but the executive director of Common Cause told the Dallas Morning News that such activity smacks of a “lobbyist shakedown.” Next, published reports revealed that lawyer Green had worked successfully to secure a state parole for a family friend and associate of a Green family business who had been convicted of defrauding investors of $30 million (the Greens were not linked to the fraud). The man had loaned $400,000 to the Green family, most of which had been forgiven in various transactions. Finally, Green appeared in an infomercial, sitting in his Capitol office and walking through the halls of state, for Focus Factor, a company that sells nutritional supplements to “supercharge your brain.” When word of this made the rounds, he asked that he be edited out of the infomercial. Forget the ethical issues; the real scandal is, Who decided that Rick Green was the exemplar of a supercharged brain?

Suzanna Gratia Hupp

Suzanna Gratia Hupp is articulate, striking, and charismatic. She gives a rousing speech. She has had to cope with sudden tragedy in her life, the death of her parents in the 1991 Luby’s Cafeteria massacre in Killeen. She ought to be an inspiration to her House colleagues and a rising political star. Sad to say, she is on a different path.

When Hupp has a bad idea, it’s a doozy. One of her bills would have sealed from the public (including potential employers) the list of persons who are licensed to carry concealed handguns. Another proposal would have created a right to privacy in the Texas Constitution that critics said would negate open-meetings and open-records laws. And these bills weren’t even close to being her worst. That dubious honor goes to one that would have let principals and superintendents in counties with fewer than 20,000 people pack heat in school. Mercifully, the only bill she was able to pass concerned the Clearwater Underground Water Conservation District.

Hupp can be a tenacious adversary in debate, but she has a tendency toward the melodramatic, playing the role of a Greek chorus commenting on the action. “Many of you may find it difficult to vote against this,” she said during the hate crimes battle, as she offered an amendment to increase the penalties not just for hate crimes but for all crimes of violence. The gratuitous remark made clear that her amendment was just a “gotcha!” ploy to force the bill’s supporters to cast a politically dangerous vote against increasing penalties for heinous offenses.

The problem with Hupp is that she would rather have the adoration of the fringe than the respect of the mainstream. She is the belle of the Black Helicopter Caucus, the name given by mainstream Republicans to a small group of their dissident and alienated brethren. All of this flared up in the session’s final week, when Hupp attacked a fellow Republican’s bill to electronically read driver’s licenses for the bearer’s age only, to prevent teenagers from buying alcohol. Said Hupp: “This poses a huge threat to our privacy . . . We have absolutely no way of knowing what the person behind the counter is keeping.” The response: “I agree. There are black helicopters flying all over Texas.”

What a waste.

Chris Harris

An unwritten but fervent addition to modern theology this session was the Prayer of the Committee Witness Under Questioning by Chris Harris: “Why me, Lord?” Time and again, Harris violated common courtesy in his mean-spirited treatment of members of the public who testified before one of his Senate committees. Lowly state employees, a hapless businessman who opposed one of his bills, an unpaid state board member—all were subjected to painful public tongue-lashings that would have tried even Job’s patience.

He revels in his reputation as the biggest, meanest bully in the Texas Legislature. “I think I better loosen my tie,” he began menacingly before launching into a tirade against a title company representative who opposed his bill on surveys. At the end, the stunned committee chairman could only say to the poor fellow, “Welcome to the Texas Senate.” When a Department of Public Safety employee failed to show up for a hearing, Harris wanted to issue a subpoena. Sure, the chairman nodded, we could do that. Or we could just call his office. The call produced the witness a few minutes later. Harris’ bizarre grilling of DPS board member Colleen McHugh likewise prompted sympathy from other committee members. At a break, someone gently asked if she would like a glass of water or soda. “Chivas?” suggested Senator Mike Moncrief. Then there was the day that Moncrief was trying to pass a nursing home reform bill. When Harris, whose law firm has represented nursing homes, kept asking unfriendly questions, Moncrief noted that he might have a conflict of interest. “Will you shut up?” Harris exploded. Other senators were stunned.

Harris’ defenders—and there are some—argue that he occasionally puts his bullying to good use, such as when he castigated the House for penny-pinching on Medicaid. Others point out that he fights for children in need of child support or health care. But on balance, his erratic behavior sends the wrong message to citizens, whether they are recipients of a tirade or witnesses to one. The Capitol and the government belong to the people, not to legislators. When Harris mistreats a citizen, he is mistreating his boss.

Fred Hill

If intentions were all that counted in politics, Fred Hill would not be on the Worst list. He holds heartfelt beliefs about ways that he would like to make the world a better place, and he fights for them. For years he has advocated cracking down on drunk drivers. Another of his targets is greedy lawyers. Worthwhile causes, to be sure. So what’s the problem? Starting out with the best of intentions, he ends up with the worst of results. Like the cartoon character Yosemite Sam, he trains his gun on the enemy only to shoot himself when someone sticks a finger in the barrel.

Exhibit A: The House is debating a proposal to increase the amount of money that the families of Texas A&M bonfire victims can recover in a lawsuit against the university. Hill is worried that greedy lawyers will take too much of the money for themselves and leave too little for the families. So he offers an amendment to limit the lawyers’ share. Who could object to that? Well, lawyers. The Legislature is full of them. They race to the microphone to defend their profession. The focus of the debate shifts from bonfire victims to plaintiffs lawyers. The moral force of the issue dissipates, and the proposal goes down in defeat. It was one of the lowest moments of the session—and the outcome was entirely predictable.

Exhibit B: Hill has tried for the previous three sessions to pass a tough bill making it illegal to have an open container of alcohol in a car. Three times he failed because the bill was too tough for Texas’ alcohol-friendly culture. This year the bill passes, thanks to its new sponsor, Best honoree Jim Dunnam of Waco. Dunnam’s bill isn’t as tough as Hill’s version, but it is a lot better than the current law, which requires an officer to see the alcohol being consumed, and it has the support of Mothers Against Drunk Driving. But that didn’t stop Hill from complaining about its shortcomings. Or us from complaining about his.

Mike Jackson

Mike Jackson raises an intriguing philosophical question. He is the pluperfect example of furniture—a legislator so inconsequential that he is indistinguishable from the desks and chairs. But are there degrees of furniture? Is there a point at which a lawmaker is so removed from the norm of participation and contribution that he ceases to be furniture and becomes a Worst? This metaphysical issue, never before confronted, must be answered in the affirmative. Just as the finest examples of real furniture can evolve into museum-worthy art, so has Jackson, by doing less than any senator in memory, evolved into more than run-of-the-mill legislative furniture. Put him on display in the Bullock museum.

This is not to say that Jackson was totally idle. The highlight of his session was trying to amend a bill prohibiting teens from riding in the bed of a pickup by exempting hayrides. Too bad it failed. His own legislative program consisted of such featherweight bills as an infinitesimal change in the rules for servicing portable fire extinguishers; the creation of the State of Texas Anniversary Remembrance Day Medal; permission for county auditors to audit the promotion and development funds of navigation districts; and the like. You could pick the student council president from most Texas high schools, put him in the Senate, give him a competent staff, and he could have done as well.

Jackson wasn’t the only senator with a light legislative package; his Harris County colleague, John Whitmire, filed even fewer bills. But the comparison doesn’t help Jackson one bit. Whitmire is a player. He had a leading role in getting Bill Ratliff elected lieutenant governor. He asks intelligent questions in floor debate. He’s a factor in the budget-writing Finance Committee. He is extremely knowledgeable about criminal-justice policy. One of the bills Whitmire handled—a study to create a system of drug courts—could have a significant impact on public policy. None of this can be said for Jackson. The House, with 150 members, can afford a few featherbedders. The Senate, with the same workload spread among just 31 members, can’t afford even one.

Carlos Truan

High maintenance, low performance: if Carlos Truan were an automobile engine, he’d have been relegated to the scrap heap long ago. Unfortunately, he is the dean of the Senate, practiced in the art of longevity—and nothing else. He doesn’t do his homework nor does he contribute; he just takes up everybody’s time. Sometimes it seems that if he would just go away, or at least forgo his oratorical meanderings, the Senate could wind up its business in half the time. “Carlos Truan” is a two-word rebuttal to the argument that the Texas Legislature needs to meet more often than 140 days every two years.

His specialty is the phantom complaint. He objects that a bill will do X when in fact it does Y. He worried that a bill setting accounting standards for school districts would hurt poor districts. (It would not.) He worried that a bill requiring consumer disclosures on credit life insurance would cause poor people to purchase it. (Not even close.) His questions reveal nothing except how unprepared he is. Once, he began to harrumph that a bill would deny college admission to poor children. Puzzled looks ensued around the chamber. An embarrassed silence filled the air, finally to be broken by Lieutenant Governor Ratliff: “Senator, . . . this is about bats.” Truan had launched into a passionate argument about another of the author’s bills, which had to do with educational opportunity, while the rest of the Senate was considering bat conservation. If Truan was for a bill, he still complained. After signing on as a co-sponsor of the teacher health insurance bill, he peppered the lead sponsor with hostile questions during floor debate and wondered aloud about national health insurance.

Even the trivialities were beyond his ken. One day he interrupted a committee hearing to introduce a group of young people whom he had just met. Oops. Wrong group. “Let the record reflect that we will not recognize you to introduce phantom constituents,” said the chairman. Let the record reflect that we do recognize phantom senators.

SPECIAL AWARDS

BEST QUIP

Buster Brown, Republican, Lake Jackson

After the Senate formally declared the pecan the state’s official health nut, he said, “I thought Senator Moncrief was the official Health nut.”

BEST YOGI BERRA-ISM

Tommy Merritt, Republican, Longview

When asked who had helped him draw up a redistricting plan that neither the Democratic leadership of the House nor the Republican caucus endorsed, he replied that he had done it “single-handedly, with the help of others.”

MOST DUBIOUS ARGUMENT

Eddie Lucio, Jr., Democrat, Brownsville

Urging his colleagues to adopt his bill delaying the start of school until later in the summer, he said, “Not one of the senators on the floor today started school before Labor Day and we all turned out fine.”

BEST PROP

Gene Seamon, Republican, Corpus Christi

Protesting the proposed new boundaries for his district, which stretched from Corpus Christi into the Rio Grande Valley, he donned a life jacket to show that he’d have to go across the bay to reach his constituents.

FURNITURE

The furniture list for the seventy-seventh legislative session—recognizing those who participated little more than the desks and chairs—consists of a single person, Governor Rick Perry. This fate befell him not by chance but by choice. Having ascended to the governorship by filling a vacancy, he opted to lie low and play safe, an aspiration that proved to be within reach. His legislative program was lighter than helium. His top priority—shutting off a primary challenge in 2002 from U.S. senator Kay Bailey Hutchison—lay outside the Capitol and appears to have been attained. On the rare occasions when he got involved in a big issue, his intervention came late and was not welcomed. He said he would not try to halt the hate crimes bill but got caught doing so; in the resulting uproar, the bill gained the support it needed to pass. Senators in his own party were furious when he scotched a fee plan to fund nursing homes; they said he had reneged on a deal and he said he hadn’t. His accomplishments included holding the line on taxes, some good appointments, and little else. His limitations, however, were noticeable only to insiders; outside the Capitol, Perry’s absence from the fray did him no harm. He didn’t lead, but the Legislature found its way without him.

MALAPROPS

The Legislature has a colorful language all its own. The mixed metaphor (“a time bomb headed for a banana peel”) and the redefinition of a term (“rig count” to describe the number of television cameras on tripods) are staples of the legislative lexicon. This session’s special contribution was the malaprop—the misuse of a familiar word. Our favorites:

arthur n. One who writes a bill. “Who is the arthur of Senate Bill 5?”

mute adj. Without practical significance. “That’s a mute point.”

ominous adj. Referring to the combination of many elements into one. “What happened to the ominous courts bill?”

physical adj. Pertaining to government spending. “What are the physical implications of this bill?”

president n. A principle or ruling that serves as a guide for future decisions. “This bill sets a bad president.”

spend v. To waive or bypass. “I move to spend the rules.”

susceptible adj. Agreeable to. “The amendment is susceptible to the arthur.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Best and Worst Legislators