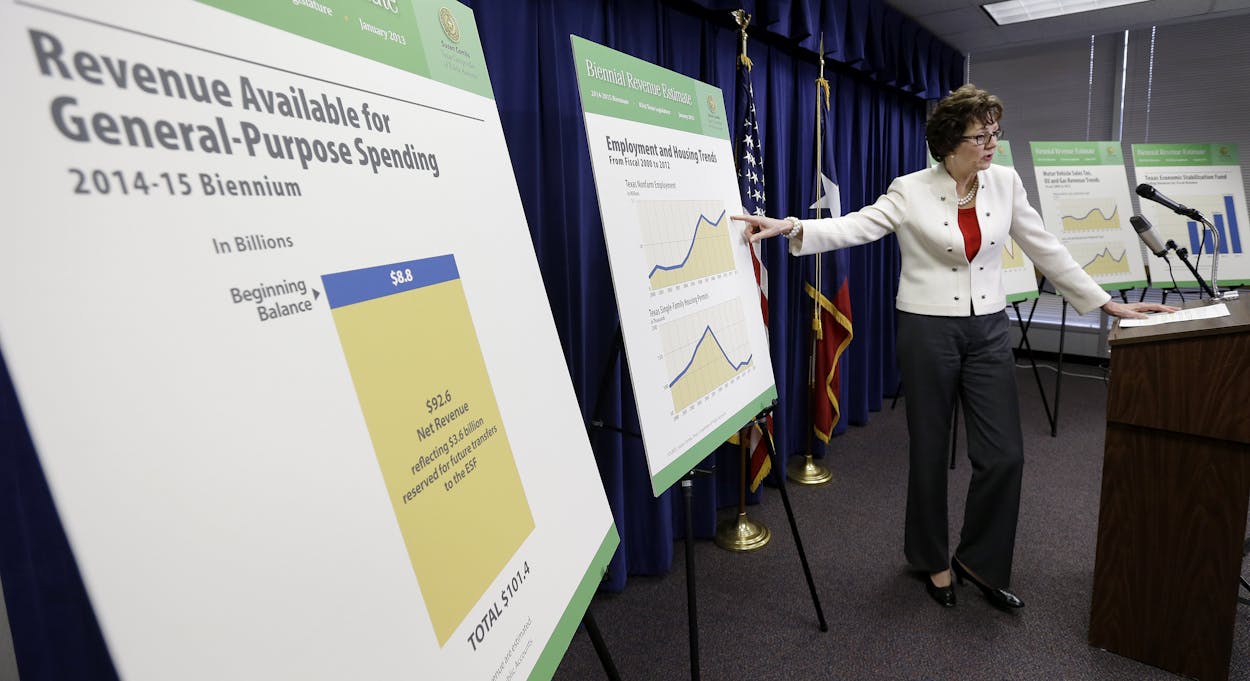

When Susan Combs, the Texas comptroller, announced her Biennial Revenue Estimate on Monday, Democrats might have thought it was good news for public education funding in Texas. The comptroller was projecting that Texas will have $101.4 billion to spend in the 2014-2015 biennium. The budget passed during the 2011 session represented a $5.4 billion cut to public education, compared to 2012-2013 funding levels and commitments the state had made about spending prior to that session. The comptroller’s new projection includes a surplus of $8.8 billion that will be left over at the end of this fiscal year—a surplus, in other words, that amply exceeds the public ed cuts.

There were cuts across the board in 2011, of course, but the cuts to education had been more controversial than most. Parents had seen the effects in their children’s classrooms, and the state is currently facing several lawsuits, because the Texas constitution requires the legislature to make “suitable provision” for public schools.

Democrats were quick to call for the funding to be fully restored. Many have observed that if the comptroller’s 2011 Biennial Revenue Estimate hadn’t been so wildly below the mark, there would have been no need to cut the public education budget in the first place. Republicans were just as quick to push back. In a press conference on Wednesday, Rick Perry said that state spending on public education has grown significantly, and has outpaced the growth in school enrollment. In fact, Perry said, Texas’s public education spending “has been pretty phenomenal.”

In other words, the Republicans are doubling down on fiscal discipline. Just because the state has more money, in their view, doesn’t mean it should spend more money. If anything, party leaders argue, the rosy new revenue estimate proves the wisdom of the austerity approach: Texas got through the past two years without putting any extra tax burden on businesses or workers; that, in turn, helped goose the state’s economic recovery, which is why the comptroller now expects revenues to be so healthy in the forthcoming biennium.

Muddying the waters is that there is, apparently, some internal disagreement among conservatives about how abstemious Texas actually is. Some Republicans point to the fact that overall state spending has grown at a faster rate than the state’s population. Perry is the most prominent figure in this camp, but also prominent are some of Perry’s critics, who point out that most of this spending surge has transpired under his watch. Other Republicans, however, dispute the suggestion that the state is getting sloppy. Most of the spending growth, they argue, can be explained by inflation, population growth, federal rules (about, for example, Medicaid eligibility), and structural factors. On the latter part, they mean the 2006 “tax swap,” which was designed to lower Texas’s high property taxes and created a new margins tax to make up the difference. The margins tax, notoriously, hasn’t brought in as much revenue as expected, but it is collected and distributed by the state, in contrast to the property tax, which is collected locally and (for the most part) administered by local authorities. So even if the swap has resulted in less overall money for the public sector in Texas, a significant portion of public spending has shifted from the local level to the state.

In other words, some conservatives think the state has become more bloated. Some conservatives think that the state is no more swollen than usual. But both camps agree that efficiencies (or further efficiencies) can be found. Some Republicans are even calling for further tax cuts, although others, such as state representative Dan Branch, have expressed doubts about that.

Despite that, the state is going to do some spending this session. “It’s been a while since we have done what I would call Texas Big Things,” said Phil King, a Republican state representative. Even the Republicans are looking for greater investment in transportation and water. David Dewhurst had, back in November, called for the state to take $1 billion out of the rainy day fund for such projects. A bill filed this week by Allan Ritter, a Republican state representative from Nederland, calls for twice that amount to be taken out and used to advance the state water plan. Such thinking isn’t entirely in conflict, though, with the overarching call for fiscal discipline. These are infrastructure projects, and infrastructure projects—fixing a road, building a new reservoir—generally represent a one-time, fixed expense (despite the need for future maintenance). At a conceptual level, then, the Republican support for infrastructure projects isn’t out of line with their insistence on small government.

This helps explain why public education is going to be the focal point of the budget battles. If there’s one sure bet about the state, it’s that the population is going to keep growing. That means Texas’s public school enrollment is going to grow. So not only is public education a recurring expense, it’s bound to be a growing expense, in real terms.

Of course, if Texas’s population is growing, it stands to reason that the state’s revenues will also grow. But if the growth in education spending outpaces the growth in revenues, the state will be in a difficult position. Texas ranks very low in terms of spending per student. But it does spend a greater share of its general budget on public education than the national average. The explanation for that apparent discrepancy is that the state’s overall spending per capita is among the lowest in the country; Texas students get a relatively big slice of a miniature pie.

Furthermore, Republicans would argue that there’s no consensus about what a state should spend per student. There may be a correlation between per-student spending and educational outcomes, but it’s not a perfect one. (Some, in fact, are skeptical of the correlation.) Democrats, however, will continue to maintain that Texas’s low spending per student is a dangerous underinvestment in the state’s future, particularly given that Texas schools aren’t producing the highly skilled workforce that the state wants as it is. Dewhurst, for one, expects the courts to agree with them.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Business

- Susan Combs