This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In the emotion-parched arena of prostitution, Jim Bunch was a fool for love. He signed the many letters he wrote to hookers “Love, Jim,” and he fell hard for the women who sold him their affection by the hour. Bunch had no more business running an escort service than he did igniting a state government scandal. But he did both, for love and money, and paid with his life.

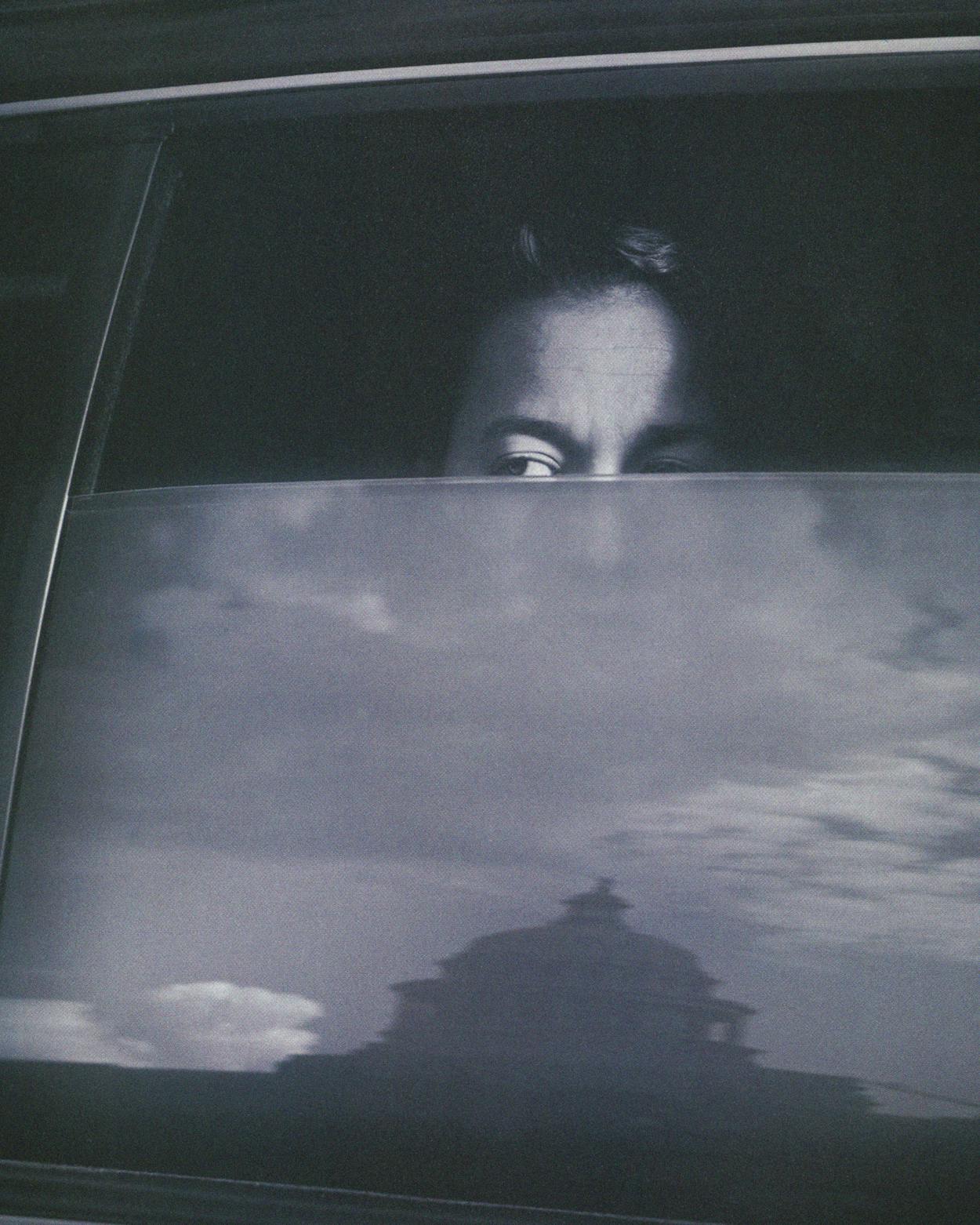

Jim Bunch was but a humbled gray figure in a year that has been shaded garishly by Tonya Harding, the Bobbitts, and O. J. Simpson. When, upon Bunch’s arrest, it came time to tell his story—the story of a state employee, who, from his cubicle at the Texas Department of Human Services, ran a high-volume escort service that was said to involve not only Austin’s most fetching prostitutes but also a blue-ribbon client list of state politicians and the local jet set—he did not perform up to the standards of Heidi Fleiss, Hollywood’s self-promoting glamour madam. Instead, he shrank from the camera lights like the nocturnal creature he was, and ultimately blew his scandalous life away.

Today Bunch’s brother says flatly, “The media exposure is what killed Jim.” But James Almer Bunch’s hidden life was wobbling recklessly long before its exposure and violent culmination. The underworld of prostitution tempted Bunch, his girls, and his clients with just enough hedonistic adventure to ensnare them all. That Bunch was right in the center of the action, where he had always wanted to be, only meant that he could not fully recognize the precariousness of his double life until its inevitable collapse.

Here is how the stage was set in 1991: Jim worked for the state, Natalie worked for Aimes (pronounced “Amy’s”) Escorts. Jim evaluated regional Medicaid facilities. Natalie turned tricks. Jim was twice divorced. Natalie was strung out on heroin. Jim loved Natalie. Perhaps the feeling was mutual.

Jim Bunch was 43 and new to Austin, having just transferred from the Department of Human Services (DHS) office in San Antonio, where he had spent all of his adult life. His family would later attribute Bunch’s troubles to his new environment: “In moving to Austin,” says his brother, “he probably became a little lonely and met another side of life that he wasn’t prepared to handle.” Bunch was an intelligent and good-humored man, but he had always been shy around women. A boyhood bout with polio had left him with a slight limp. By his senior year in high school, his hair was thinning rapidly. Bunch was entirely acceptable looking, but remained bedeviled by his shortcomings. As the son of a career military man, he moved from one city to the next throughout his schooling. Just out of high school, he began dating a woman for the first time, a girl from his hometown of Mexia. When she ended the relationship after two years, Bunch was crushed. He attempted suicide by swallowing a bottle of aspirin.

Through most of college, Bunch seldom dated. After graduating from Stephen F. Austin University in 1970, he was hired by the DHS and moved to San Antonio. His first marriage lasted eight years, his second marriage five. Insecure, lonely, and unlucky in love, Bunch sought out “another side of life” in Austin—the side that forfeits romance for the sake of control. He dialed the phone numbers of the escort services listed in the Yellow Pages of the Austin phone directory. But he could not resist his softer impulses. Bunch was a generous man, and the prostitutes he hired were often desperately poor. The escort service call girls may have had it easy compared with street prostitutes—who worked all night on South Congress and gave all their earnings to their pimps lest they be whipped with wire coat hangers—but none of them was living the Pretty Woman life. Some were teenage runaways whose first introduction to Austin was a middle-aged man’s proposition. Others had husbands in jail, children to feed, drug habits to support; the cause of their poverty did not matter to Bunch. His state salary was a little more than $30,000, but he had credit cards and used them liberally to buy meals, clothes, or whatever else the prostitutes required. He may have missed his family back in Mexia, but Bunch discovered another family life in the Austin underworld—one in which his generosity would always be needed. “He couldn’t say no to any of us,” recalls one prostitute.

Above all, he could not say no to Natalie Dudney. Natalie was redheaded, buxom, and about 35, a veteran by call-girl standards. She had been plying her trade in Austin for nearly two decades, through the massage-parlor era of the mid-seventies, which followed the closing of Hattie’s on South Congress in 1960 and of La Grange’s infamous Chicken Ranch in 1973. She had seen the once wide-open Austin prostitution business go underground, the bandidos biker gang take over the business in the early eighties, and the Asians claim their turf by the middle of the decade. Natalie had acquired a long police record and a taste for heroin along the way, but she was charming and savvy, and Bunch found her impossible to resist. At his request, she moved in with him in July 1991. Time and again Natalie would disappear, returning weeks or months later, broke and wasted. Bunch always took her back, and after delivering a few unheeded lectures on the evils of heroin, he would nurture her back to health so that she could go on calls again.

Natalie’s employer was Sherry Beard, the 25-year-old owner of Aimes Escorts. Sherry had been arrested for prostitution in 1985 at 19, but otherwise ran a discreet operation out of her South Austin home and knew to shut down the business whenever she felt the heat from the Austin Police Department vice squad. Her girls were for the most part attractive, and her extensive client list featured several prominent attorneys, doctors, lobbyists, and entrepreneurs. While dating Natalie and sometimes paying for the services of her co-workers, Bunch developed a phone acquaintanceship with Aimes’ owner that evolved over time until he and Sherry Beard were, in the words of one mutual friend, “like father and daughter.” He loaned her money, chatted with her on the phone in the evenings, and eventually was answering the escort service’s phones by having its calls forwarded to his northeast Austin home. By 1992, Bunch was helping Beard hire prostitutes.

For a while, Jim Bunch kept his two lives separate. At the DHS he was a dignified presence in his starched white shirts and his well-trimmed beard, and was known throughout the state’s regional offices as a decent and hardworking man. He spent holidays with his parents in Mexia—all holidays except New Year’s Eve, when he would drive to the north side of Austin to a place near the old Dr Pepper plant, knock on an unmarked door, pay his admission fee, step into a cavernous room filled with dance music, and celebrate the New Year with other anonymous swingers, many of them in various stages of undress. Bunch only watched the action, but that was adventure enough.

He took Natalie to the swingers’ club and celebrated the dawn of 1993. Less than two months later, on the evening of February 20, Bunch was driving Natalie and her three-year-old son back to his house when she begged him to make a stop so that she could score some heroin. After several minutes of arguing he relented. As soon as they pulled into his driveway, Natalie darted into the house and shot up in the bathroom. Bunch found her dead five minutes later. Sherry Beard happened to drive up just then and took the little boy to a carnival, while Bunch sobbed alone in his house. “Jim totally blamed himself,” recalls a prostitute who knew him well. “He hated himself.”

Jim fought with everyone he loved,” says Kelli LaRue with a leisurely laugh as she exhales marijuana smoke. “Him and me, we had a completely love-hate relationship. He was a father figure to me, but we argued every day, all day long. God, he thrived on arguing.” The 24-year-old prostitute shakes her head and her waist-length avalanche of dark red hair partly obscures her smile. “I wish he was alive today, so that I could beat the shit out of him.”

Are those the makings of tears in her eyes? She takes another drag and seems restored. Heavy metal blares from the stereo and incense fumes drift out of the living room, but otherwise her residence is orderly and distinctly middle class, replete with paintings and knickknacks of fish that match a tattoo on her ankle. (“Do you think you’re a fish or something?” a vice squad investigator sneeringly asked her recently, prompting the reply, “Yeah, I do. Fish are real easygoing until something pisses them off. Then they bite.”)

Like many fathers, Jim Bunch enjoyed reminding his “daughter” who controlled the purse strings. Kelli had wanted to buy a house, but she had bad credit; she had to threaten Bunch with leaving town before he would put the house in his name. Similarly, he balked when she asked for a loan so that she could buy a particular bedroom set, even going so far as to say that he just might buy the set for himself. But today Kelli has the bedroom set, Bunch’s old ranger truck, and a debt to him hovering around $3,500.

Kelli LaRue spends her days and nights here in a casual state of numbness—smoking pot, watching television, listening to the stereo. Her husband is on the lam, as there is a warrant out for his arrest on marijuana charges. Since she is awaiting trial for aggravated promotion of prostitution in the wake of the Bunch scandal, she is not accepting business calls. Yet Kelli neither repudiates her profession nor gives a damn what anyone thinks about her. With a total absence of self-pity, she recites her history in a wry singsong, the formative calamities reduced to throwaway anecdotes. A wild child in a gossipy small town. Living with a 35-year-old shrimper in Port O’Connor by the age of 14. Pregnant for the third time at 15, this time by the shrimper’s nephew. Her infant son taken from her by Child Protective Services the next year, following an incident in which the child fell from her lap and cut his head on the floor. Her mother’s surrender to pancreatic cancer just before Kelli’s fifteenth birthday. And fights with her father—all of which led to her flight from the Gulf Coast. And thereafter, a dark mosaic of characters and places. By 1992, Kelli LaRue was 22, unemployed, living with her 4-year-old daughter, and, as she puts it, “in a desperate situation.” She noticed an Aimes Escorts advertisement in the back pages of the Austin Chronicle and dialed the number. Sherry Beard offered her a job.

“I told myself I’d only do it for a month,” she says, laughing, conscious that this is a familiar refrain. “Then, only for a year.” But the money was too good. For each hour’s work, Sherry retained an escort service fee of $50 and Kelli got the rest, which began at a base of $100. Even on slow weeks, Sherry’s girls could earn $1,000, while a busy evening’s work could net as much as $600, and $1,000 for an all-nighter. Certainly the vocation had its inglorious moments—clients gone crazy on cocaine, wanting to be verbally humiliated, to be whipped—but for the most part the men were well behaved. “I put up with a hell of a lot worse as a cocktail waitress,” Kelly says, “and all for a one-dollar tip.”

By the time she met Jim Bunch in November 1992, the DHS quality-control coordinator had become interested in the financial possibilities of the sex racket. He and Natalie were placing ads in swingers’ magazines, through which they made more than $1,000 selling nude photographs and suggestive letters. In a letter to a prostitute he hoped to lure into the magazine market, Bunch wrote, “I hope I don’t seem like a pervert to you but I have come to the conclusion that sex makes the world go around and there is a ton of money out there to be made if you don’t rip people off.”

Natalie’s death left Bunch emotionally reeling. For companionship, he leaned heavily on Kelli, who often spent evenings at his house answering the escort service’s line, listening alternately to sex-crazed customers and the heartsick bureaucrat. Though there was nothing physical between them, Kelli became Jim Bunch’s closest friend in his shadow life. He took her shopping, baby-sat her daughter, and finally persuaded her to join him in sex-oriented entrepreneurial schemes. In the summer of 1993, Kelli and Jim began placing women-seeking-men ads in the Austin Chronicle: “Sweet young thing seeks generous man for fun and support.” The ads were wildly successful, even if most of the respondents were initially surprised to learn that this mildly seductive campaign was nothing more than a solicitation by a $150-an-hour prostitute.

As fate would have it, Bunch’s capitalist urgings coincided with the vice squad’s renewed interest in Sherry Beard. Word on the street was that a bust was imminent. Sherry needed to bail out in a hurry. Knowing this, Bunch told her that he would like to take over the business. In October 1993 Sherry Beard sold the Aimes Escorts client list to Jim Bunch in exchange for an automobile down payment he had made for her in the past. Before fleeing Texas, Sherry took Kelli LaRue aside. She advised Kelli to copy the client list in case Bunch went down. “You be careful,” she told her. “Jim is going to get arrested. He’s not street-smart.”

The escort-service game in Austin is so well understood by its players as to be farcical. On one side of the playing field are the 37 escort services listed in the Austin Yellow Pages, each of which is suspected by the Austin Police Department (APD) of engaging in the state offense of selling sex. Another dozen or so prostitution fronts appear in the guise of Austin Chronicle personal ads under the headings “Women Seek Men,” “Variations,” and “Adult Services.” On the other side of the playing field are Richard McFadin and Rudy Vasquez, the two vice squad officers assigned to the escort-service beat. The numbers do not favor the officers, and the most discreet services manage to stay in operation for years by going about their business quietly and occasionally snitching on their competitors. One of the most well-established operations in town is owned by a resident of Baltimore, Maryland. Another veteran owner is widely believed to be providing information to the Austin police. She declined an interview for this article, coolly saying, “I’m a very private person.”

“The typical escort-service owner is a sleazebag, but he’s a cut above street pimps, especially when it comes to business sense,” says former vice squad commander Gene Freudenberg, who is now a private detective in Round Rock. Under Freudenberg—known as Friggenberg by his adversaries on the street—in 1986 the APD vice squad busted the notorious Tony Brubaker, who kept 1,500 square feet of office space and racked up an estimated $600,000 in escort-service profits. That same year, a credit card sting operation managed to put 33 prostitution-related Austin operations out of business. “We expect business to decline drastically,” proclaimed a police department spokesman, but it was a naive prediction. The remaining escort services continued to do good business, and soon other opportunists rushed in to command a slice of the prostitution pie. One of these was a captain stationed at Bergstrom Air Force Base who was found to be a partner in Austin Escorts and was given a ten-year sentence in August of last year, two months before James Bunch took over Aimes Escorts.

Bunch knew enough about the risks to avoid the most obvious police stings. Sex could not be discussed over the phone, and callers were required to give their names and addresses and have listed telephone numbers. To keep tabs on his girls, Bunch initiated a staff directory. Each girl filled out a form giving her name, address, phone number, age, measurements, and schedule. The form was similar to those used by other escort services, but Bunch added a line marked “Limitations.” This gave his prostitutes the option to list calls they would refuse. Among the responses the Aimes employees gave on the limitations line were “no blacks,” “not submissive,” and “none really.”

Under its new ownership, Aimes’ business was booming. By Kelli LaRue’s estimate, the phone at Bunch’s residence rang anywhere from fifty to one hundred times daily, out of which ten to twenty service calls were consummated. Assuming each service averaged one hour, Bunch was pocketing from $500 to $1,000 a day, while his girls netted double that amount. Bunch employed up to twenty prostitutes at any one time, including one male model to accommodate female clients. (During Bunch’s four-month ownership of Aimes, the number of female callers wanting either a man or a woman was probably less than twenty, according to Kelli LaRue. The escort service did not cater to male homosexuals.) The client list, maintained on index cards, exceeded three hundred. Bunch aggressively pursued the market. He answered inquiries to his escort service ads in the Austin Chronicle with letters offering everything from lingerie modeling and photo sessions to “erotic correspondence,” “sexy wake-up calls,” “fantasy role-playing,” “threesomes and moresomes,” and “maid service in the nude.” The list of people receiving these letters included attorneys, health care professionals, engineers, and professors. Another Bunch advertisement solicited participants in “house parties for swingers,” for which Bunch charged couples $100 and single males $250 to congregate at a Howard Johnson hotel suite and engage in group sex. Other follow-up letters promised monthly “singles” and “couples-only” parties, and a possible “ladies-only” party “for our Bi ladies.”

There was money to be made in the sex business, and Jim Bunch seemingly wanted all of it. He continued to take in wayward prostitutes and scatter his money around, but he also demanded that his girls work longer hours and ranted continuously that they were cutting him out of some of their tricks—which, of course, they were. “Jim got really greedy,” says Kelli LaRue, “and the greedier he got, the more careless he got.” To keep the business going at all hours, he allowed “real fruitcakes who didn’t know anything about the business end” to answer the phones, she says. He added to the staff directory a few questionable prostitutes, including a trio from Minneapolis who were accomplished thieves. Worse still, Bunch put to work a seventeen-year-old girl who had moved into his house, and who in turn—unbeknownst to him—brought a fifteen-year-old friend into the fold, which meant that Aimes Escorts was now committing the second-degree felony of employing minors as prostitutes.

Though Bunch did not do drugs, he began to sell cocaine to his clients. This was an outrageous flouting of escort-service etiquette, as drug peddling gives law enforcement agents an easy opportunity to shut down an otherwise discreet operation. “I had a lot to say about that,” says Kelli LaRue, whose vices do not include either cocaine or alcohol. “But Jim didn’t care about the danger. He couldn’t see past the money.”

One of the customers who paid Bunch for his girls and his drugs is an Austin professional who shall be known as Christopher. Wealthy and urbane but traumatized by a divorce, Christopher began to pay for sex. “Some of the girls I met recommended Aimes to me,” he says. “You know, there’s a lot of prostitutes out there who are really hard core: hard to look at, hard to talk to, hard to trust. Bunch had the girl-next-door types.”

Christopher became an Aimes regular. When Bunch answered the phone, Christopher would ask, “Who’s around?” (“The object,” he says, “was to have this constant spin cycle, one ingenue after the next. I mean, obviously I wasn’t looking to have someone move in. I was hiring them so I could move them out. The game was variety.”) Bunch would reply, “I’ve got this new girl you’d really like.” Then he would ask, “Are you interested in some pool?” If Christopher said yes, that meant he wanted Bunch to deliver an “eight ball” of coke (two and a half grams) to his house, followed by a prostitute who would do the drugs with him.

Sometimes Christopher invited his friends over and entertained them with Aimes prostitutes and coke. Sometimes he hired several and kept them to himself. Sometimes he enlisted a prostitute just to sit around with him and do drugs. “Except for Kelli, they were all doing drugs,” he says. “They were addicted to the money, the attention, and the cocaine. It was a trap for all of us.” More and more, Christopher found himself staying up all night with Bunch’s girls. “We were binging on sex, alcohol, and drugs,” he says, “and it was this wretched downward spiral we couldn’t figure out how to stop. There would come a certain point when the meter would cut off, so to speak. But they’d stay over anyway. It was safe, and they didn’t want to come down alone. They’d talk about the depravity of it all, and they’d start crying, and I couldn’t see having sex with them again because, through the pain, we had gotten too close.”

Christopher stopped calling Bunch’s number and went into drug and alcohol treatment. But Bunch would not let one of his most lucrative clients off that easily. He began to phone Christopher at his office. He sent him letters that described the beautiful new prostitute he had enlisted recently. When all that failed, Bunch began to drop packets of free cocaine through Christopher’s mail slot.

By January 1994, Christopher was back on the active client list.

Throughout his management of Aimes Escorts, Jim Bunch continued to perform his work at the Department of Human Services with his customary efficiency and attention to detail. But Bunch crossed the line he had drawn between his two lives, and that would prove to be fatal.

Though he had told no one at Aimes, Bunch kept client and staff lists on his office computer. He made frequent calls to his girls and customers from his DHS cubicle. “He was outrageously open,” says one of Bunch’s friends. “People could walk right by, see him counting money, and hear him talking about prostitutes over the phone.”

Perhaps the dual pressures of trying to increase profits at Aimes and maintaining a double life were getting to Bunch. Though he hid his moodiness from his family, he was showing signs of chronic depression. He spent much of his free time in bed, in the dark, eating chocolate bars while watching two television screens. He hit on the girls frequently, as male escort-service owners often do, but the prostitutes could see that he was not so much sexually driven as lonely. As he had written, sex did make the world go around, but perhaps Jim Bunch was tiring of a hollow world that spun endlessly.

At the beginning of February, Bunch decided to sell the business. He had received an offer of $25,000 from a former professional football player but decided instead to give the list to one of his girls. Bunch visited an accounting firm in order to assess the escort service’s tax situation. He then asked the girl he had selected as his successor to sign a letter that he would forward to the phone company, verifying the transfer of the Aimes Escorts phone line. That letter was faxed to Bunch’s office on February 14, 1994.

Bunch did not know that the fax was intercepted by DHS investigators, who had been monitoring him for several weeks. He did not know that one of his co-workers, apparently disturbed by his arrogant flaunting of his moonlighting job, had reported him to the investigators. Nor did Bunch know that two computer diskettes on his desk, containing staff directories, client lists, advertising follow-up letters, and erotic correspondence, had been copied and thoroughly perused by state officials. All of this explains why Jim Bunch looked bewildered when vice squad officers dragged him out of bed on the morning of February 15, searched his house, confiscated numerous boxes of evidence, and led him away handcuffed and shirtless to the police station, where waiting DHS officials informed him that his 23-year career was being terminated on the grounds of official misconduct.

News of the sensational arrest thundered through Austin. A prostitution ring being run out of a state agency! The Department of, ahem, Human Services, no less! Your tax dollars at work! The media spotlight shifted daily, first to Bunch’s audacious use of state property for illicit purposes; then to the client list, which, police acknowledged after reading only a portion of it, included the name of at least one state legislator; then to the vice squad’s revelation that Bunch may have pimped for girls under seventeen. Local wags salivated over the possibilities until speculation became gossip and ultimately took on the status of fact: “They say he ran the whole operation right out of the DHS. They say he made millions. They say he had teenagers and Tarrytown housewives on his payroll. The say the whole damned Legislature’s on the list!” Referring to the number of well-heeled Aimes clients who contacted the police department to find out whether their name appeared in the Bunch files, vice squad investigator Rudy Vasquez smiles and says, “The phones got real busy around here.”

Jim Bunch was released on a $5,000 personal recognizance bond on February 16, the day after his arrest. He talked to his family on the telephone and ordered them not to come to Austin. The local media were hounding him; one television reporter planted a microphone just outside his front door. Having heard of the fabled client list and imagining the ramifications of such a list’s being in the hands of the police, Bunch’s brother asked, “Jim, is your life in danger?”

No, Bunch assured him—concealing from his family, as always, the fact that the real danger rustled within his despondent heart. On the advice of a friend, he began to take Prozac to combat his depression. His life, once so neatly compartmentalized, was now in a shambles. The DHS job he loved so dearly was no longer his. Though several individuals had contacted Bunch’s attorney offering assistance, only one DHS co-worker had called him personally to extend support. His girls were now in deep trouble. Several had been questioned by the police, and eventually a few of them would be arrested. Against the orders of his attorney, he called Kelli LaRue. “Jim, you know we’re not supposed to be talking,” she said and hung up on him.

The secret life he had fought so hard to keep from his family, particularly his parents and his daughter, had now been made excruciatingly public. Could anyone be hoped to understand his story, now so grotesquely inflated and embroidered by the media? He hadn’t owned Aimes for “at least two years,” as the Austin American-Statesman had reported; the business had been his for only four months, and he had already arranged to turn it over to someone else. The suggestion that he had gotten rich off of prostitution was ridiculous. Where was his money? He had none! He’d given it away as soon as it fell into his hands. What did he have to show for his endeavors? Only a Ford Bronco, and he was still making payments on it! And minors—that misconception depressed him the most. He would never have employed a girl under seventeen. That the fifteen-year-old had gotten into the business through one of his girls was news to him. Jim Bunch would never stoop to such exploitation. He was always decent to his girls. He always helped them.

Then this business about the list. Yes. There were a couple of legislators, but no more than that. What escort-service list didn’t include a few politicians? And sure, the list featured several prominent names: wealthy attorneys, doctors, lobbyists, developers, academics, restaurateurs, a local television personality, a former professional athlete, and other notables. But, with a few exceptions like Christopher, the big money wasn’t coming from the big names. It was coming from men who, like Bunch himself, were of modest means and perhaps modest self-image and who were spending all of their disposable income on women who made them feel virile and adventurous for a fee. The money was coming from a local businessman who blew his livelihood on crack. It was coming from a bureaucrat with the Austin Fire Department and from a middle-aged federal employee who still lived with his parents. It was coming from an auto mechanic who liked to get drunk with his friends and hire three or four women at a time. It was coming from a blues musician who asked the prostitutes to make noises into a microphone during sex. It was coming from a scary young man who lived in a shabby Riverside apartment and who liked to be “rushed,” or knocked around. It was coming from one accountant who liked to whip the girls and another who wanted to be kicked in the testicles. These were Jim Bunch’s glamorous patrons. These were the Richard Geres who kept Austin’s Julia Robertses in business and on cocaine.

By the early morning of February 18, Jim Bunch had decided not to count on anyone’s understanding. On four pieces of paper, he scribbled a series of notes to nineteen people or groups. He began by writing good-byes to his parents, his son and daughter, and his brother. To a nineteen-year-old prostitute whom he had taken in, he wrote, “I love you as a daughter,” and asked his parents to take care of her, as she had no family of her own. To Kelli LaRue he gave his love and said, “This is the only way out for you.” He thanked the Austin vice squad for their professional treatment of him but then warned, “You are fighting a losing cause. The [escort] services are the only things that these girls can survive by.”

The notes moved on, extending thanks to friends and apologies to the Department of Human Services while reminding the world, “I did a good job and cared about the clients and staff.” To the Austin TV stations, he wrote, “Boy, you were brutal . . . It’s a shame I couldn’t stick around for the movie of the week.” In another moment of irreverence, Bunch admonished the city to fix the air conditioners in the courthouse holding tanks. But he let down his guard when it came to addressing Natalie Dudney: “On the 20th it will be a year since you died. You will never know how much I love and miss you. I think I want all this to happen as punishment for not being able to help you.”

After notations to his attorney, the Internal Revenue Service, and a co-worker, he jotted down one last paragraph: “Finally My Girls: I hope you know that I cared about each of you. I am sorry for the pain I have caused you. I hope this takes some heat off of you. I should have done it sooner. I forgive all outstanding debts (like you were going to pay me anyway). Sorry I was so stupid. I know this puts all of you in a financial bind. I made it so easy for them. I can’t believe I was so stupid. Take care of yourselves.”

And with that, James Almer Bunch put the note in his car, drove five miles from his house to the parking lot of his old workplace on the corner of Lamar Boulevard and Fifty-first Street, stepped out onto a grassy median, and revealed the one final secret he had kept from everyone, including his girls: the fact that he owned a revolver.

“I’m out of the game,” says Christopher over dinner at a popular Austin restaurant. Fresh from a long stay at a rehabilitation center, he indeed looks healthier. His therapist has ordered him to say away from prostitutes, and he has done so, despite the provocative calls he has received from a few of Bunch’s former girls. “Prostitution is a trap for men and women,” he observes. “The girls and the guys con each other, and they con themselves by telling themselves that it’s just an economic relationship like so many marriages are. Anyway, I’m through with the conning.”

“Hmmm,” says Kelli LaRue with a knowing smile when informed of Christopher’s decision. “Well, we’ve heard that before about him, haven’t we?”

She has seen enough in her 24 years to infect whole populations with lethal doses of cynicism. Kelli wishes Christopher the best—after all, why not?—but in her experience, one might do well to count on the worst and learn to live with it. While Jim Bunch’s other prostitutes have scattered like wild seeds—some of them are already working for other escort services, some are under arrest, others are nowhere in sight—his closest female associate sits and waits for her part in the Bunch fiasco to play itself out. She awaits trial as Bunch’s suspected co-manager, and her attorney, Allan Williams, predicts, “They’ll try to shift the blame of the whole operation onto Kelli, just so they’ll have something to show for their efforts after Bunch killed himself.”

Kelli LaRue made herself an easy target by being the only Aimes call girl to make the trip to Mexia on February 20, the day they buried Bunch. Heads turned and whispers filled the air when the red-maned prostitute sashayed into the crowded funeral home. But she picked her way through the congregation, oblivious to the gawking mourners, until she came upon Bunch’s mother and brother. She told them who she was and that she loved Jim, and then she began to cry. They embraced her, and while Jim Bunch lay in state, his two families were united at last.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Business

- TM Classics

- Crime

- Mexia

- Austin