It was a scene suspended between a Kafka nightmare and the lunacy of Lewis Carroll, a bizarre conclusion to the long national tragedy that began with the raid of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco in February 1993. Bill Johnston, the defendant who stood before a black-robed judge in a St. Louis courtroom awaiting sentencing, was charged, in effect, with concealing evidence of his knowledge of the FBI’s use of pyrotechnic weapons in its final assault on the compound. The former assistant U.S. attorney in Waco, who had helped prosecute eleven surviving Davidians for conspiring to murder federal agents during the initial raid on the compound, Johnston was the improbable villain turned up by a $17 million investigation led by special counsel John C. Danforth—making him the only person to be indicted as a result of all the hearings and investigations into federal misconduct at Waco. Everything about the courtroom scene was upside down and backward. Far from being guilty of covering up what happened at Waco, Johnston, more than any person in America, was responsible for exposing the truth. At the time when the FBI was still denying that it had fired the kind of ammunition that could have caused the fire that killed 82 men, women, and children at the compound, Johnston had broken ranks with his own superiors in the Department of Justice to write Attorney General Janet Reno that there was evidence that the FBI had used pyrotechnics. And yet here he was, a strapping six-four hunk of rawhide—a man who looked more like a rodeo cowboy than a dedicated professional lawman—standing with his shoulders sagging and his head bowed in shame and humiliation, certain that he was on his way to prison.

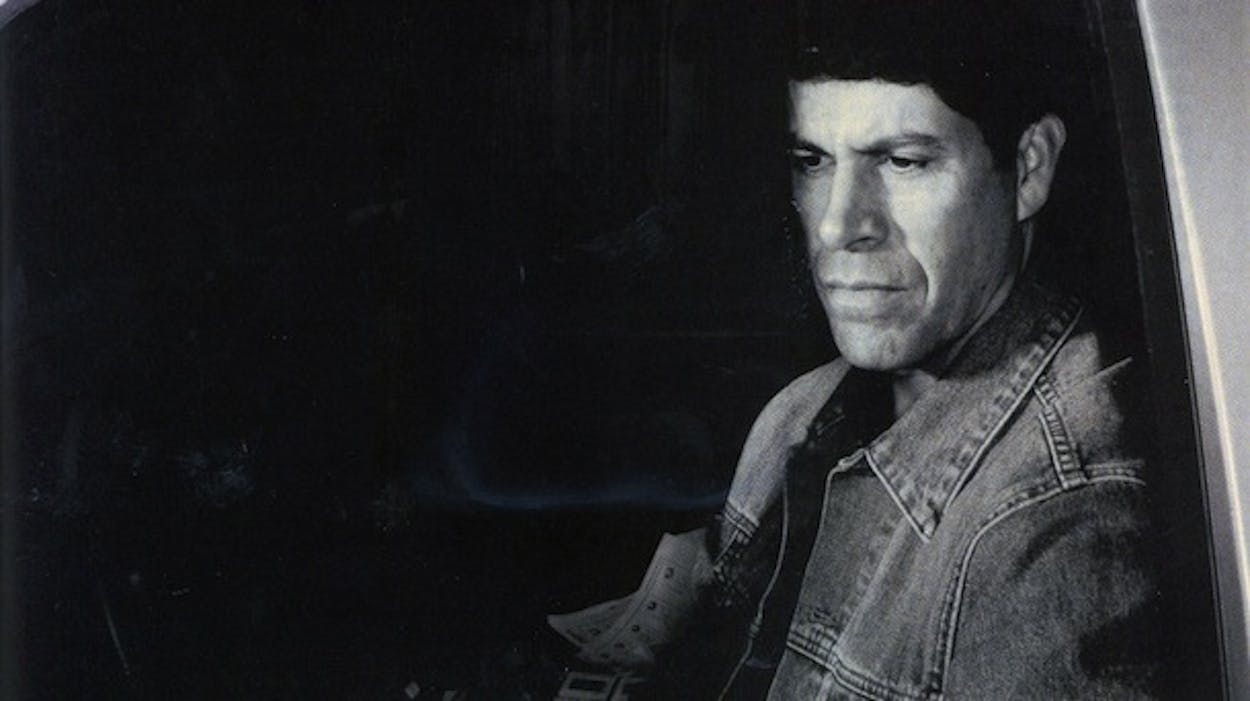

I was in St. Louis because Bill Johnston is a friend of mine. I have known him for nearly ten years and have written about him several times, most notably when he and two friends, U.S. marshals Mike and Parnell McNamara, instigated the search that led to the arrest, conviction, and execution of notorious serial killer Kenneth McDuff (see “Free to Kill,” August 1992). Johnston, 42, has the kind of instinctive integrity that Gary Cooper personified in Hollywood. A former Sunday school teacher and the author of Texas history books for children, Johnston doesn’t drink or smoke or swear; the strongest language anyone has ever heard him use is “golly.” He is almost too nice for a profession in which duplicity and mendacity are not only common but laudable.

Johnston was originally charged by the Office of Special Counsel with two counts of obstructing justice and three counts of lying to investigators and the grand jury. All of those charges were later dropped in return for Johnston’s plea to a single count of misprision of felony, which covers a variety of sins, including the failure to perform an official duty. The crime, unfortunately, was his own. I wish that I could tell you that Bill Johnston is an innocent victim of a government vendetta, but he isn’t. In 1999, responding to a subpoena to send all of his Davidian-related documents to his superiors, Johnston came across notes that he feared could be interpreted to implicate him in a cover-up, ripped them from a notepad of interviews conducted six years earlier, and later lied about it. What he did was wrong, but if he had not been such an outspoken critic of the Justice Department, he probably would have been given a slap on the wrist, as were others involved in the Waco fiasco.

The accusations of obstruction of justice have a distinct whiff of Orwellian irony. For more than six years the FBI and the Justice Department denied that pyrotechnics were used during the assault. Johnston didn’t obstruct justice—he pursued it, even if it meant blackening the eye of his own agency. That may explain why Danforth and his minions went after him. They made it clear from the start that they expected Johnston to serve prison time and permanently lose his law license. Friends who tried to raise money for Johnston’s defense fund found themselves subpoenaed to appear before the grand jury. “They literally conspired to ruin his life,” says retired Texas Ranger captain David Byrnes, who was in charge of the crime scene at the compound.

Johnston’s guilty plea ended an ordeal that left him a physical, emotional, and financial wreck. His legal bills were soaring. He had resigned from the job that had been the core of his life for thirteen years and opened a private practice, but nobody wanted to hire a lawyer with federal charges hanging over his head. He might well have won a jury trial, but the only realistic choice was to snap up the bone that was offered—a recommendation for probation rather than prison time. But then, three weeks before Johnston was scheduled for sentencing, the Office of Special Counsel suddenly withdrew its recommendation. The reason? Johnston had spoken to a reporter for Texas Lawyer, saying, accurately, that he had not pleaded guilty to any of the charges in the indictment—although he did admit to facts that supported several of the charges. The Office of Special Counsel contended that the interview was an attempt “to trivialize his guilty plea by now denying much of his criminal conduct.” James Martin, Danforth’s top lieutenant, informed the court, “Johnston continues to try to paint himself as the white knight who tried to force the government to tell the truth …”

Would Danforth get his final measure of flesh? Or would Judge Charles Shaw reject the argument? We were about to find out.

When the shooting started at the Davidian Compound on February 28, 1993, Johnston was at the command post for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) strike force. He had been assigned to give legal advice to the ATF. The first hours of the standoff were absolute chaos. No one could make a decision. The FBI’s Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) had been flown in from its headquarters at Quantico, Virginia, but no one was working on the criminal investigation or attempting to preserve evidence at the crime scene. Johnston asked the Waco police department to photograph the damage done by Davidian gunfire to military helicopters used in the raid. Then he persuaded the ATF to put the Texas Rangers, instead of federal lawmen, in charge of the criminal investigation. This action was the beginning of his downfall at Justice. Johnston was already considered a maverick by his boss in San Antonio, U.S. attorney Ron Ederer, because of the McDuff case. Ederer, a lame duck holding over from the George Bush administration, believed that federal authorities had no jurisdiction over the murderer and chewed out Johnston for getting involved. When Ederer heard what Johnston had done at Waco, he was furious. During a meeting with the Rangers and crime-scene experts from the Department of Public Safety lab, Ederer motioned for Johnston to follow him down the hall for a private conversation. “Why are you giving them advice?” he demanded to know. “Because they need it,” Johnston replied. He said that he was working on protocol for searching the buildings once the standoff ended. Ederer reminded Johnston that his only job was to prosecute. “I’ve got work to do,” Johnston snapped, turning and storming out of the room.

By the third day, the law enforcement community had split into warring camps—the FBI and the U.S. attorney on one side and the ATF, the Texas Rangers, and Johnston on the other. Johnston stayed in the Rangers’ camp, coordinating the criminal investigation. The Rangers believed that their best evidence in the homicide case was the dozen or so vehicles that the Davidians had left parked in front of the compound. During the shoot-out, ATF agents had used the vehicles as cover, and the vehicles were riddled with bullet holes and stained with blood. Since investigators knew which cult members had been at which windows, the lines of trajectory could establish who had fired the fatal shots. Ranger Byrnes solicited a promise that the FBI would respect the integrity of the crime scene, that the vehicles would not be moved unilaterally. But on a Sunday afternoon, about three weeks into the standoff, Johnston was horrified to hear from ATF agents that the vehicles were being bulldozed into heaps.

Johnston wasn’t a team player, but then he never had been; out in the boondocks, far from the San Antonio office and light-years from Washington, he had mingled with local law enforcement officers and considered himself one of them. He was totally unprepared for the high-stakes bureaucratic warfare in which he would soon become involved.

On March 23 Johnston took the most daring initiative of his career. Bypassing Ederer, he wrote a letter directly to Reno, the newly appointed attorney general, complaining that FBI actions and missteps were destroying evidence and threatening the effort to prosecute the Davidians. Before mailing the letter, he showed it to David Byrnes. “Bill, this looks like a suicide note to me,” the Ranger captain warned him.

Johnston’s letter got action. Reno sent her deputy assistant attorney general, Mark Richard, to Waco. Richard eyed the situation and instructed the FBI to cooperate and respect the role of the Rangers. But the letter was viewed as a virtual act of mutiny by rank-and-file lawyers at Justice, who never forgot or forgave. The letter had so poisoned the well that Johnston wasn’t told about the HRT’s plan for a final assault on the compound until the evening of April 18, just hours before it began—and he was told not by the FBI but by the Secret Service.

Already on the outs with his colleagues at Justice, Johnston further angered some members of the team of prosecutors appointed to try the surviving Davidians by fully cooperating with a review of the Waco tragedy by the Treasury Department. He was passed over as the lead prosecutor in favor of Ray Jahn of the San Antonio office, who was named to head up a five-member team, which included his wife, LeRoy, and Johnston. Ray and LeRoy Jahn had been stars within the ranks of Justice since the early eighties, when they successfully prosecuted Charles Harrelson for the murder of federal judge John Wood in San Antonio. They were angry with Johnston for cooperating with the Treasury review, which they feared would damage their case against the Davidians. For the trial, Johnston was given the relatively minor assignment of proving how and from whom the Davidians got their machine guns and explosives. But a critical moment for Johnston occurred a few months before the case was tried: In November 1993 the team of prosecutors traveled to Quantico to interview HRT members, a trip that seemed routine at the time. Six years later, it would become central to the unraveling of Johnston’s career.

The conviction of the eleven Davidians did not put the questions about the tragedy to rest. Congress held hearings on the Waco debacle in 1995, and the turf war between Justice and Treasury was on again. Subpoenaed to testify, Johnston further alienated his bosses by preparing a written statement that did not conform to Justice’s party line—that the FBI had done a fine job in Waco, had worked closely with the Texas Rangers, and had brought a difficult case to a successful conclusion. But when he appeared before Congress, the questions focused mostly on the ATF raid rather than on how the FBI had conducted itself. Johnston did not know at the time that pyrotechnics had been fired, but others who did know either lied or misled Congress. Several internal Justice and FBI documents, as well a Justice briefing for Reno, denied the use of pyrotechnics. Richard Rogers, the FBI commander who had ordered the firing of pyrotechnics, sat directly behind Reno—and remained silent—as she assured Congress that only non-pyrotechnics had been employed. After the hearings, the Davidian affair dropped off the media’s radar screen for nearly three and a half years. But one person was still asking questions about Waco—documentary filmmaker Michael McNulty. His 1997 film, Waco: The Rules of Engagement, conjured up a number of wild conspiracy theories, but it also raised the question of who started the fire. McNulty had repeatedly written letters to the Justice Department requesting permission to examine the evidence locker in Austin where the Rangers had stored thousands of pieces of material from the Davidian investigation that had never been inventoried. Each request was curtly denied. Johnston, who had always believed that the government had nothing to hide, decided to allow McNulty to look at the evidence, after first clearing it with Justice’s head of public affairs. The filmmaker discovered a shell casing from a pyrotechnic grenade. McNulty wrote the Justice Department about what he had found and told Johnston and the Rangers as well. Johnston was skeptical, but he and the Rangers decided to take another look at the evidence. By the summer of 1999 a DPS expert had established that the shell casing was indeed from a pyrotechnic M651 tear gas round.

When Johnston read the expert’s report, he sent a series of frantic phone, fax, and e-mail messages to Bill Blagg, the new U.S. attorney in San Antonio, alerting his superiors that Justice and the FBI had a big problem. Yet Reno and others continued to stand by the FBI. Meanwhile, the torts division at Justice was outraged to learn that McNulty had shared his discovery with lawyers representing the Davidians in their $675 million lawsuit against the federal government. Marie Hagen, Justice’s top lawyer in the civil suit, telephoned Johnston, furious that he had permitted the filmmaker to see the evidence.

The truth emerged on August 24,1999, when Dallas Morning News reporter Lee Hancock wrote that a former senior FBI official had admitted that the agency had fired two pyrotechnic tear gas grenades. The next day the FBI publicly acknowledged that it “may have used” pyrotechnic devices. Prosecutor Johnston had been right—but if he thought that the fallout from Waco was now behind him, he quickly discovered otherwise. A few days after the newspaper stories ran, Blagg called to say that he was faxing Johnston a troubling document that the Jahns had found. The fax was part of the notes taken by the trial team’s paralegal during the November 1993 Quantico meeting in which a member of the HRT’s Charlie Team revealed that “military gas rounds” had been used. The paralegal had written Johnston’s name in the margin, which suggested that Johnston may have attended this meeting. Johnston had been at Quantico at the time, but he had no recollection of such a meeting. Nor would he have understood the meaning of “military” rounds back in 1993. But he knew it all too well now. Johnston thought long and hard about what to do. He kept remembering something his father, an assistant district attorney in Dallas in the fifties, liked to say, “I sacrifice no principle to get this job; I’ll sacrifice none to keep it.” Then he sat down and wrote another letter to Reno, informing the attorney general that the FBI and lawyers from her own department had long withheld key information about Waco. Once again Johnston’s letter to Reno got a response. She appointed John Danforth, the former United States senator from Missouri, as special counsel, with orders to get to the bottom of the Davidian debacle.

Although the fax from Blagg to Johnston was confidential, a report about its contents appeared in the Morning News the day after Danforth’s appointment. When Johnston realized that the fax had been leaked, he gave Lee Hancock a copy of his letter to Reno. His estrangement from Justice had turned into open hostility. In a matter of hours the story was making national headlines. Soon Johnston was telling his story to 60 Minutes, National Public Radio, and other forums.

Johnston was now haunted by the possibility that he had attended the fateful November 1993 meeting at Quantico. That fear led to his downfall. Flipping through a yellow legal pad of notes from that trip, trying to refresh his memory, he discovered one cryptic page of scribbling. It read in part: “Charlie. One green military (incind).” The misspelled abbreviation apparently indicated that incendiary rounds had been discussed. He still could not remember the meeting, but he knew now its importance: If he had been there—if he had understood clearly that the FBI had fired pyrotechnics—then he had failed to reveal the truth. Johnston ripped the offensive page from his notepad, well aware that he was sliding down the slippery slope of criminal activity. Only then did he obey orders to send his Davidian-related documents to San Antonio.

Not long after that, Johnston arrived at his office to find a Justice Department computer technician downloading files from his computer. When she saw Johnston, she left abruptly. That’s when Johnston decided to resign. “I just don’t want to be on their side anymore,” he told friends.

On three occasions in the fall of 1999 and the spring of 2000, Johnston traveled to St. Louis to answer questions from the Office of Special Counsel, unaware that prosecutors had zeroed in on the meetings at Quantico and were poring over the notes of trial team prosecutors. Nor could he have guessed that they had discovered that a page was missing from his notepad and reproduced it through a technique called indented handwriting analysis. Unaware of his vulnerability, Johnston underwent questioning without an attorney. The Davidian trial team had broken into groups in that 1993 meeting at Quantico, so there was no way for investigators to establish which prosecutors had attended which meetings—except from their notes and what they remembered six years later. The Office of Special Counsel focused on one particular meeting in which HRT member David Corderman acknowledged that he had fired pyrotechnic rounds. None of the team members remembered this meeting. But notes taken by John Lancaster, a prosecutor assigned to the team from Justice’s Terrorism and Violent Crime Section, read “Corderman—military gas round … fired 1-4 incendiary rounds.” Notes apparently from the same interview taken by paralegal Reneau Longoria have the revealing terms “bubblehead” and “military gas round” and a misspelling of the word “incendiary.” The Office of Special Counsel discovered no notes to prove that LeRoy Jahn had attended the meeting but suspected that she had. After Johnston’s third appearance before the grand jury—and after he had lied about the missing page—he was told by an Office of Special Counsel staff member that he hadn’t attended the Corderman meeting, that he had probably learned about it from one of the others. The misspelling of “incendiary” suggests he had seen Longoria’s notes. But the revelation came too late to help him.

In its final report the Office of Special Counsel concluded that all the trial team members understood clearly what was said and shared responsibility. But only the Jahns and a blacked-out name that is presumably Bill Johnston’s “went to great lengths” to cover up their knowledge and obstruct justice. Johnston’s misconduct, however, “went further than that of the Jahns.” Johnston had not only removed from his notes a key page relating to the FBI’s use of pyrotechnic tear gas but had also falsely certified that he had produced all relevant documents. On the advice of Gerry Goldstein, a prominent San Antonio attorney, the Jahns refused to sign the same certification. The Jahns went out of their way to manipulate witnesses and shift the blame to Johnston, the report states. But Johnston had repeatedly lied about the existence of the concealed page and the Office of Special Counsel seemed particularly angered by what it saw as Johnston’s attempts to take the high road in letters to Reno and statements to the media. “He made these statements knowing that he had engaged in precisely the deceptive conduct which he was condemning,” Danforth’s office said. Finally—unlike the Jahns—“Johnston’s felonious conduct may be proved by direct, probative, and admissible evidence.” Prosecutors hate to indict unless they can also convict. Johnston had made it easy for Danforth to use him as the fall guy.

By the time Johnston pleaded guilty and came up for sentencing, the only unanswered question was motivation. The indictment used the word “scheme” repeatedly, implying that he had plotted to hide his own culpability and make himself into a hero (for example, by allowing McNulty to sift through the evidence and discover the M651 casing). “It’s not atypical for people trying to pass themselves off as whistleblowers to make public remarks and try to put the focus on other people,” assistant special counsel James Martin told me later. This theory requires people to believe that Johnston knew about the use of pyrotechnics from the beginning. Even if he had been at the meeting with the HRT in November 1993, he and the other members of the trial team, including the Jahns, were obviously confused by the semantics employed by the rescue team members, which used a number of terms interchangeably—military rounds, cupcakes, bubbleheads, incendiaries, hot gas, and penetrators. At one Quantico meeting, LeRoy Jahn had asked, “What is a cupcake round?” Apparently no one had used the correct name—pyrotechnics. There is no reason to believe that Johnston attributed any significance to the terms until after McNulty discovered the M651 shell.

After listening to both sides, Judge Shaw decided that Johnston was motivated by nothing more sinister than survival. Though his crime was real, it did not rise to the level of a Machiavellian plot or deserve a prison term. Instead, the judge gave him two years probation. It was a victory, but I didn’t feel like celebrating. The case never should have been pursued.

If Danforth had been truly pursuing wrongdoers, there were plenty to choose from:

• The ATF commanders, Chuck Sarabyn and Phillip Chojnacki. The Texas Rangers filed federal charges of lying to investigators against both men. They were fired by the ATF but later rehired. Justice declined to prosecute.

• FBI commander Richard Rogers, who gave the order for the HRT to fire pyrotechnics, then remained silent while his superiors denied that pyrotechnics had been used. Justice declined to prosecute.

• The Jahns. The Office of Special Counsel recommended that they be removed from their jobs. Justice declined either to fire or to prosecute them.

• James Cadigan, an FBI crime-scene investigator who made a note about a “40 mm gas grenade,” then concealed the notepad in his attic for seven years. “Putting notes relating to one of the most significant investigations in FBI history in an attic is highly suspicious,” the Office of Special Counsel observed. Justice declined to prosecute.

• Jacqueline Brown, an FBI lawyer who knew about the use of pyrotechnics but failed to pass on the information to Justice and then lied at least four times to the special counsel. Justice declined to prosecute.

But each of these wrongdoers got the benefit of the doubt. There was no government cover-up or conspiracy, Danforth concluded, just “human foible.” Of Jacqueline Brown, Danforth writes, “I believe what happened in this case was that this fairly young lawyer simply goofed, simply failed to do an adequate job.” Honest or even bad mistakes, the special counsel decided, are not evil, merely human.

Not if your name is Bill Johnston. Not if you’re a maverick. Not if you’re a whistleblower. Not if you tell the truth about the FBI. Not if you’re the only guy who doesn’t have friends in Washington. No one connected to the horror of Waco comes off clean. Nobody escapes censure. And Bill Johnston, the one person who did demonstrate honor and integrity, is the one who is punished. Somewhere, David Koresh is smiling.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy