Editor’s Note: This story went to press when Bill White was still running for Senate. Mayor White officially announced his candidacy for governor on Friday, December 4.

Mayor Bill is on the move. Strapped into the passenger seat of an unmarked Lincoln Town Car, cell phone stuck firmly to his ear, he rolls through the vast grid of streets. He issues orders, barks out instructions. In the waning days of August 2005, something terrible has happened, and in some ineffable, fate-ridden way, it has fallen to him to fix it.

That terrible thing is Hurricane Katrina. The storm, which has slammed into the Gulf Coast, has also loosed a flood of evacuees. Of these, 200,000 have landed in Houston. There is no guidebook or FEMA manual that addresses such a massive shelter operation. In Dallas, 30,000 victims have arrived, and Mayor Laura Miller is already complaining that her city is nearing the saturation point. In Houston, 30,000 people will come through the Astrodome alone.

This is Mayor Bill’s problem. This is why he is pounding through the city at all hours of the day and night in the wilting, late-summer heat. He is learning, as the rest of America will soon realize, to its horror, that the federal government cannot be counted on for much of anything. Nor, really, can the State of Texas. Nor, really, can anyone else. No one knows what to do.

Except, as it turns out, Mayor Bill. In those first moments of chaos, he makes a large conceptual leap: The evacuees are not going home. Almost no one believes this, because it’s unthinkable that a single city could possibly absorb so many people. Mayor Bill believes this. Even better, he has a plan. Well, it is more of an objective, with the details to follow. But it is an extraordinary idea. “The overriding policy goal,” he will say later, “was to treat people the way we would want to be treated. We wanted people to be on the path to living with independence and dignity, to finding work and getting their children in school.” Permanently. Mayor Bill is old-fashioned: a Sunday school teacher who believes in the mysteries of God and in the quaint notion that people are inherently kind and generous. Each time he welcomes someone into the shelters, he offers a verse from the New Testament: “When I was hungry, you fed me. When I needed shelter, you took me in.” The Book of Matthew is the overriding policy goal.

In press conferences and interviews, he pitches this idea to Houston, and the city signs on. Its residents become, in effect, the people Mayor Bill believes them to be. Within a week, a staggering 100,000 individuals are mobilized in churches, schools, nonprofits, and businesses. One thousand doctors from Houston’s Medical Center—the best hospital in the world—are dispatched to provide care. Problems are swiftly solved. When Mayor Bill learns that thousands of evacuees can’t get prescriptions filled because they lack the proper identification, he responds by dictating a crisp letter to the CEOs of the major pharmacies, asking them to relax their rules. He has the entire Houston-area congressional delegation sign it and faxes it off. Within 24 hours, fully stocked pharmacies miraculously appear at the main shelters, staffed by pharmacists who suddenly have no trouble bending the rules.

Mayor Bill does not brook delay. He calls up a friend who is a director at Walmart and essentially demands that the company, the third-largest corporation on earth, put the full power of its global supply chain at his personal disposal. This happens immediately. Thus Mayor Bill can get anything he wants—cots, blankets, clothing, refrigerators, food—in hours instead of days or weeks. He holds daily logistical meetings at the George R. Brown Convention Center, which becomes the command post for the relief effort. He cuts off political speeches; he bans turf battles. He shames FEMA. In a meeting federal officials proudly announce that they now have an 800 number that will solve all the problems the storm victims are having registering for aid. White sends two of his lieutenants into a hallway to try it out. The number is useless. Mayor Bill demands to know why.

He does this sort of thing again and again with FEMA. He aligns himself closely with Republican Harris County judge Robert Eckels, and the two men work as one. Along the coast, government at all levels is breaking down. In Houston, as each minute passes, the relief effort becomes tighter, better organized, and more efficient.

Still, Mayor Bill has a problem: Where is he going to put all these people? FEMA’s answer: trailers and temporary shelters. His answer: apartments and permanent dwellings. He digs up every landlord he can find—eventually there will be some six hundred of them—and tells them, “The only place that these fellow Americans of yours can stay is in apartments, so if there is an apartment that has been abandoned, rehab it, fix it up. If it is due to go online in a month, have people work overtime.” Plumbers and electricians and building inspectors are recruited and deployed. Empty nursing homes are converted. With astonishing speed, reminiscent of wartime mobilization, the city and county come up with 30,000 empty units, ready for occupancy.

But that doesn’t answer the question of who is going to pay for them. The feds have already bailed out. There is no precedent for what is happening, and if there is anything a bureaucrat fears worse than losing his job it is those two words: “no precedent.” So Mayor Bill invents a program without anyone’s permission. It is essentially the Mayor Bill Plan, backed only by the full faith and credit of Mayor Bill. Without waiting for Congress or the White House, he issues thousands of housing vouchers that bear the seal of the City of Houston. People can give them to landlords to pay rent, but the apartment owners know there is nothing behind the vouchers. They want to know how they are going to get their money. Mayor Bill looks them in the eye and tells them, in his best Sunday school teacher voice, “I believe the American people, once they understand what is happening, will do the right thing.” Implausibly, the landlords agree.

As it turns out, Mayor Bill is right about his fellow Americans. Several weeks later, after the majority of evacuees are already living in Houston-area apartments and their children are enrolled in school, Congress passes a bill authorizing money to pay for the voucher program. In the meantime, 150,000 people are resettled in Houston, 120,000 of them in those apartments. Mayor Bill does it all for $250 million. And his plan becomes the model for the federal Disaster Housing Assistance Program, which profoundly changes the way the country will handle similar emergencies in the future.

Four years later, Mayor Bill—that would be the Honorable Bill White—is once again rolling through the city. But this time he is on a Trek road bike. On a still, humid Sunday morning in late July, the 55-year-old is making one of his trademark city-sweeping rides for which he has become locally famous. To ride with the mayor is to understand his relationship with this enormous, multiethnic stew pot of untrammeled laissez-faire-ism, this sprawling 640-square-mile patch of coastal plain so large that Chicago and Philadelphia could sit inside it and still have room for Baltimore and Detroit.

Today he starts in Memorial Park, on Houston’s west side, cuts an arc north and east through Independence Heights, then across to Airline, down through Freedmen’s Town to the heart of downtown, and back: a thirty-mile loop. The first thing I notice is that he knows the city virtually street by street. People had told me this—that he has a knowledge of the city, especially inside Loop 610, that even some cops and firefighters don’t have—and I had not believed it. But to ride with him is to believe it. He has an extraordinary memory for minutiae and knows all the street names and where the churches and crack houses are, where the schools and historic buildings are, where he has ordered homes torn down and replaced with his “Houston Hope” residences, inexpensive, subsidized dwellings that are popping up all over the city.

And he knows people. This is perhaps the most surprising thing. Over a three-hour ride, mostly on backstreets, White stops and talks to dozens of people with whom he is acquainted, from elderly blacks on the sidewalk in Independence Heights (“Say hi to Pastor for me”) to Hispanics at Canino’s Produce on Airline Drive (where he speaks Spanish) to city employees, who all seem to like him. These are people he actually knows.

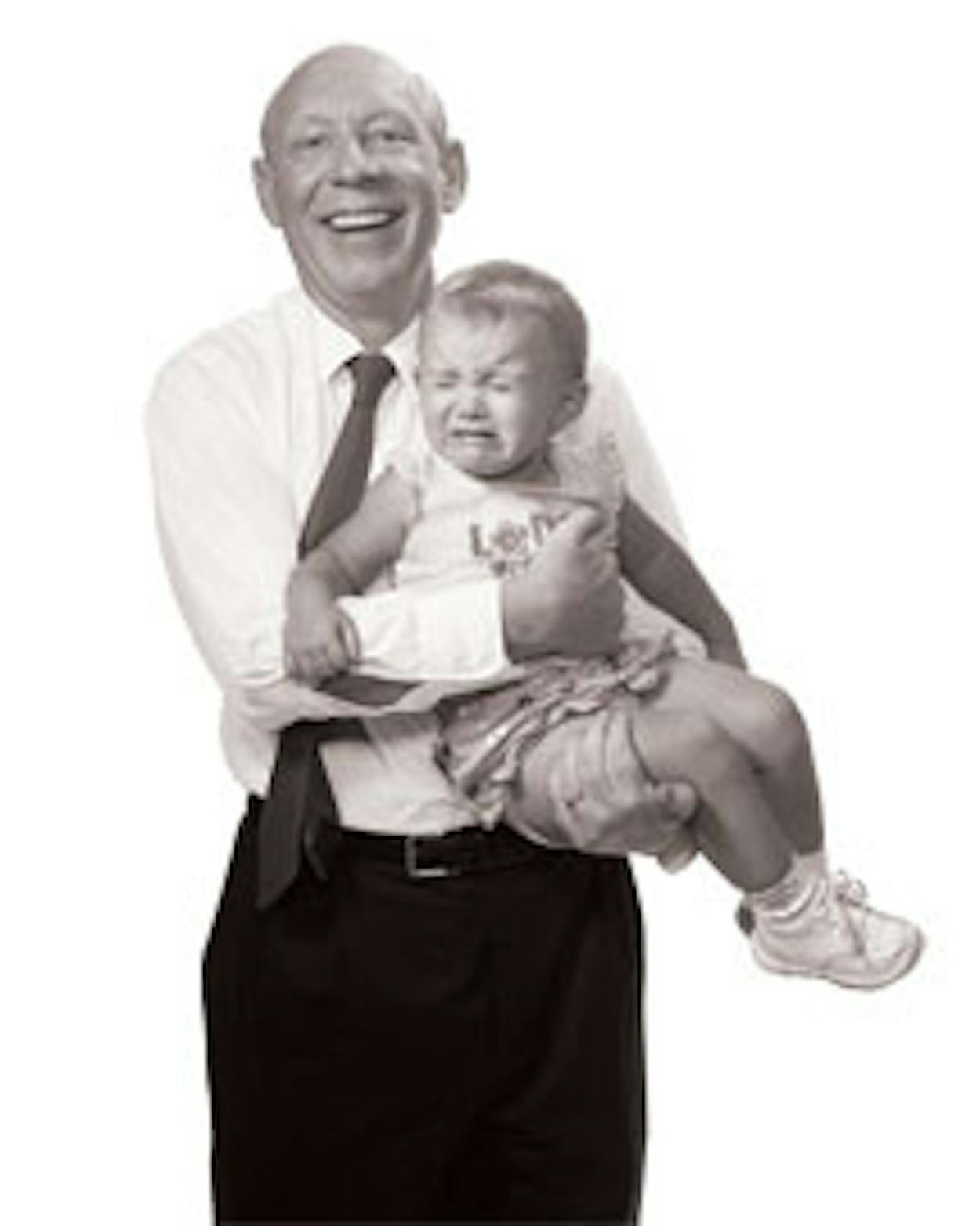

They are, however, far outnumbered by the people he does not know who recognize him and say hello. White has distinctive looks that were once thought a political liability: a bald pate with a fringe of reddish hair and features—notably his ears—that are perhaps a size too large for the superstructure. But since Katrina, when White was constantly on television and became a sort of instant celebrity, his appearance has become a huge asset. People recognize him at a distance, even in colored spandex and a helmet. He is “the Katrina guy,” the mayor who is so popular that he was reelected with margins of 91 percent and 86 percent for his second and third terms, respectively, carrying huge majorities of voting blocs, from Fifth Ward blacks to white, Galleria-district Republicans. “Hi, Mayor Bill!” cries a woman in a small group of people on a residential lawn in the Heights. They all wave and smile. At the market, folks cluster around him, taking photographs. There is something else about his face: It is kind and friendly. People are drawn to it.

Riding with him I get the sense—it’s almost surreal—that I am touring a small town, not the nation’s fourth-largest city. This is enhanced by the behavior of White himself, who has what city council member Anne Clutterbuck calls “an excruciating capacity for detail.” On his rides he takes note of everything from potholes and abandoned lots to apparent drug houses and crimes in the street. These notes make their way quickly to city department heads, as the equivalent of “action today” memos. Four years ago, when riding with state senator Rodney Ellis and others in Independence Heights, White came upon two men in a pickup illegally dumping building materials in an abandoned lot. He confronted them and asked what they thought they were doing. His companions, meanwhile, were concerned for his safety. “The mayor is back there saying, ‘You guys can’t do this,’ ” recalls Ellis, “and he looks like he is about to make a citizen’s arrest. I am worrying about a citizen about to get shot.” A few minutes later, a police cruiser arrived and arrested the men.

Today White spots an empty lot in Independence Heights, with a ditch full of garbage. He knocks on the door of the adjacent home, an old, ramshackle bungalow, and questions the man, who of course recognizes him immediately. White asks if he saw who dumped the garbage and gives him a number to call if he has any information. Since there is a For Sale sign on the lot, White calls the real estate agent and leaves a message: “This is Mayor Bill White. Your client’s lot is full of garbage, and I thought your client would want to know that.” Dumping offends White. It just isn’t right.

So it goes on our trip through the city. He shows me the renovations in Freedmen’s Town, the spectacular new $125 million downtown park called Discovery Green—built with combined public and private funds—that he thought up, helped raise the money for, and bird-dogged from inception to final bricks, mortar, trees, and grass. “This was a series of run-down parking lots,” he says. “Nobody knew what to do with it. Now it’s a great park. But there is also”—he points to the skyscrapers looming above—“a billion dollars’ worth of new investment going up around it.” At a market he consults with the owner, whose awning was blown off by Hurricane Ike and who is having trouble getting a city permit for a replacement. White takes notes and pledges help. Then the man’s daughter comes out with a camera to take a picture of her father and the mayor, and then more people arrive with cameras, and a small crowd gathers. White’s city rides are often like this.

After six years in office, Bill White has become something more than just the mayor of this massive megalopolis. He has been so successful and has become so powerful that it seems that he and he alone controls the city’s vast social and political machinery. This partly stems from the real power given to him by the city charter. There is no city manager, and he directs the city council’s agenda, which essentially means that nothing can come to a vote unless he says it can. He also directly oversees the bureaucracy of city government, which means that he can tell city employees what to do. They all work for him.

Partly it is the way White has wielded that power, a quiet, bipartisan, consensus-building approach, that has transformed the Houston City Council from the often rancorous foe it was under his predecessor, Lee Brown, into a docile—some would say too docile—and cooperative ally. Of more than 13,000 city council votes since he has been in office, White has lost 3. Most are unanimous. “He doesn’t like to do anything on an eight-to-seven vote,” says council member Sue Lovell. “He really wants the clear majority of stakeholders and council members to be comfortable with it and in favor of it. If you come to him and say, ‘I don’t think this will work,’ he will listen to you and sometimes come back to you and say, ‘You are absolutely right, we need to do it this way.’ ” Though a faint bleating can be heard in some quarters of city hall from council members who may have felt ever so slightly stepped on or who find White a trifle dictatorial, you can scarcely find any credible political figure who is willing to speak against the most popular mayor in memory. Calls to those who have had differences with him, including city council members Jolanda Jones, Pam Holm, and Ron Green (all of whom vote with him most of the time), were not returned.

“He has instilled confidence, and he has gotten people to trust him to such a degree that people have this feeling that the city is in great shape because Bill White has been taking care of it for six years,” says Nancy Sims, a longtime observer of Houston politics who writes a popular political blog, texas-musings.com. “There is really not a group of people that you can find that, as a whole, hate Bill White, which is a rare thing to say about a mayor.” Says Craig Varoga, a national political consultant who has worked extensively in Houston: “Even people who are unhappy or dissatisfied because of their particular issues will say that they think he has done a good job overall. A lot of that is rooted in Katrina, which was the perfect confluence of reality and politics.”

He has done it with a complex and ambitious plan that few mayors anywhere would have attempted. Against the advice of his friend, former mayor Bob Lanier, White has not cherry-picked a few prominent urban problems to solve. He has instead taken on more than a dozen major issues, many of which carried considerable political risk. He banned, for all practical purposes, lobbyists from city hall and from any involvement in city contracts, thereby cleaning up what many had come to call “the trough.” He took on the city’s legendary traffic jams and, in a series of programs, untangled some of them and sped up commuting times. He reduced the city’s property tax rate five years out of six; shored up the city’s wobbly pension system; reduced the City of Houston’s energy consumption by 6 percent, making Houston one of the greenest cities in the country; took on petrochemical companies over air pollution; added parks and libraries; cleaned up decaying neighborhoods and built affordable housing; revamped a badly managed police department, resulting in the city’s lowest crime level in decades; and signed new contracts with firefighters giving them 38 percent raises, the first salary increase in six years.

White has also made the most of the economic boom time that coincided with most of his tenure. He balanced his budgets every year—meaning that the city did not borrow to pay for operating expenses—and used the additional revenue both to cut property tax rates five times and to build up the city’s surplus fund, all while increasing key city services. When recession-bound Houston faced a $101 million shortfall this year due to declining revenue, he bridged the gap in part by drawing down on that surplus. White and his council also strengthened the city’s wobbly municipal pension fund by both significantly reducing benefits and upping the amount the city contributed to the system. These moves were not without controversy. Many people believe that the pension system will need further shoring up through increased employee contributions, and White himself acknowledged in a staff memo that “the recent downturn in the value of investments for all defined pension plans . . . can pose challenges for the future.” And there has been plenty of talk in this campaign season that White was in effect balancing his budget by using his rainy day fund. White insists that the purpose of the surplus is to cover shortfalls in hard times. Either way, voters seemed happy with his fiscal management, and Houston thus far has survived without any of the major layoffs or budget cuts that have come to define life in most large American cities. “With little more than seven months remaining in his last term,” reads a May editorial in the Houston Chronicle, “Mayor White has deftly steered Houston through both fiscal and tropical storms. His successor will have a tough act to follow.”

Indeed, Katrina is what people will always remember. Though Houston’s humanitarian response to the problem is now a source of civic pride, at the time not everybody in Harris County was keen on having what was perceived to be the dregs of New Orleans relocated to their city; a subsequent crime wave seemed to confirm their fears. Many of those evacuees have now been completely absorbed into the city’s fabric, as White had hoped and believed they would be. For his leadership in that crisis, White was honored in 2007 with the prestigious John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award and named by Governing magazine one of America’s top public officials.

It is endorsements like this, and his track record as mayor, that have propelled White into the race for the U.S. Senate. Because of term limits, he will find himself out of a job in January, and a December 12 runoff will decide whether city controller Annise Parker or former city attorney Gene Locke will take his place. Though many Democrats had hoped he would run for governor in 2010, he has announced his intention to run for the seat left open by Kay Bailey Hutchison, assuming she resigns to run for governor against Rick Perry. If she does step aside early, the race to succeed her could culminate in a multicandidate special election scramble as early as May.

At first glance, White would seem to have enormous advantages, which include his popularity in the state’s largest city and name recognition from his public role in Katrina. And he has proved that he can raise money. As of the reporting cycle that ended October 1, he has $6 million in his war chest; his closest Democratic rival, former comptroller John Sharp, has only $3.8 million. But the reality is that he is facing an uphill battle in a red state that went 55 percent for John McCain in 2008, has not elected a Democrat to statewide office in fifteen years, and where big-city mayors, even successful ones, have historically gone nowhere. He will be running against extremely well-funded Republican opponents. If White faces Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst, he will also be facing Dewhurst’s money: He dropped $10 million of his personal fortune in the 2002 election and could spend at least that much in 2010. Then there is the rather stark fact that, no matter what people may think of White personally, his candidacy amounts to a referendum on President Barack Obama himself. A vote for him means that Obama’s supermajority in the Senate increases by one. It is by no means clear that most Texans want that to happen.

To meet Bill White is to be underwhelmed. He has an open face; a slow-breaking, ingenuous smile; and a measured, courtly way of talking, in an accent deeply inflected by his native San Antonio, that does not suggest either extreme ambition or razor-sharp intellect. Most politicians talk in crisp sound bites. White, as his friend Paul Hobby once observed, speaks in footnoted paragraphs. As University of Houston political science professor Richard Murray puts it, his speech is “a maddening stream of consciousness without periods.” He does not seem, in short, to be what he is, which turns out to be a huge natural advantage.

At no time was this more true than during his fourteen-year career as a trial lawyer. White attended Harvard University on an American Legion scholarship, where he majored in economics, then went to the University of Texas School of Law, where he was editor of the law review, graduated first in his class, and seemed, according to a classmate, “ten years older than everybody else.”

After graduation he joined Susman & McGowan, a new Houston law firm whose unusual strategy was to do business litigation mostly on a contingency basis. To make money, the lawyers had to win their cases. White, who preferred this sort of risk-taking, was an almost instant success, and the firm quickly became one of the state’s most successful (its name was later changed to Susman Godfrey).

“Bill was such a superstar that he became a partner within a few years,” says Neal Manne, a partner at Susman Godfrey. “He had this great ability to analyze, on the front end, which cases would be successful. That, of course, is the whole game in this sort of practice.”

He was also devastating in the courtroom. “When Bill had a case in town,” says Manne, “there would be a crowd of people that would go down to watch, not just from our firm but from other firms. It was a phenomenal teaching experience, and it was world-class entertainment.” In 1989 White won jury verdicts in two major fraud cases. One involved a defective oil drilling tool and was at the time the largest securities fraud class action in the United States. The other also involved oil field fraud and was the largest award in the Western District of Texas. White, the son of schoolteachers who’d made very little money, shopped at thrift stores, and often had to struggle to make ends meet, earned millions. “If he had stayed with the firm, he would be a zillionaire today,” says Manne.

Though White prefers to govern by a sort of gentle consensus, he is fully capable of reverting to his more aggressive, inquisitorlike, trial-lawyer persona. No one felt this more than the refining and petrochemical companies of the Houston Ship Channel, who became the target of White’s ire because of their emissions of harmful pollutants. In the summer of 2004, White determined that Texas Petrochemicals was emitting unusually high levels of the chemical 1,3-butadiene and in early 2005 announced that he was going to sue the company. Texas Petrochemicals sought refuge with the State of Texas, which assured Houston that it had jurisdiction but then failed to come up with an enforceable agreement. White was furious. He indicated on the city council agenda that the city was retaining a high-profile plaintiff’s lawyer to go after “certain polluters.” “The next day our lawyer got a call from the company’s lawyer saying, ‘What do you want?’” says Elena Marks, White’s director of health and environmental policy. In the next few months White’s team worked out a settlement with the company to reduce its emissions over time that was contractual and enforceable. “They got a lot of grief from their fellow industry members, who said, ‘You caved,’ ” says Marks. “But they were going to lose a big, ugly lawsuit.”

White also went after Lyondell Chemical, the city’s largest emitter of the carcinogen benzene. Unable to force compliance under city laws, he tried an inventive strategy: He challenged Lyondell’s operating permit from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. “If the company believes that it’s just fine to put tons and tons of benzene in the air,” White told the Chronicle last year, in full trial lawyer mode, “then we would like to hear what scientific evidence they have that benzene is good for you.” The matter is still pending.

In July 2008 White went even further: He challenged the Environmental Protection Agency’s basic methods of estimating levels of pollutants. He insisted that because of the EPA’s flawed methods, emissions of harmful chemicals in Houston were many times what they were reported to be. The EPA’s reply, which made national news, came in April 2009. To the amazement of many, the agency agreed with White and promised to overhaul the way it calculates cancer-causing emissions from plants.

White’s stand on issues such as air quality—as well as such quality of life issues as traffic, parks, libraries, and clean energy—is what truly distinguishes him from his predecessors. Mayor Kathy Whitmire streamlined and professionalized city government; her successor, Bob Lanier, was famous for making city services work, filling potholes, repairing streetlights, cleaning ditches, and fighting crime; Lee Brown, a more politically controversial mayor, nonetheless gave the city an urban rail line and a stadium. But no one until White really focused on the way Houston residents experience life outside the workplace.

Though White had always been interested in politics, working as a page in Austin while in junior high school and registering voters in San Antonio’s Hispanic neighborhoods when he was in high school, his official political career began in 1993. That year President Bill Clinton appointed him Deputy Secretary of Energy, the department’s de facto chief operating officer. There were good reasons for the appointment. The first was that he had supported Clinton early on and had raised nearly $2 million for his presidential campaign. The second was more interesting: White was considered a leading expert on energy policy, though he had never held a real job in the field. In 1975, when he was a junior at Harvard studying natural gas policy, he had taken a semester’s leave of absence to work for newly elected Texas congressman Bob Krueger, who happened to be on the Energy and Power Subcommittee. It soon became apparent that the precocious White knew more about the subject than most congressmen. “Bill White . . . literally wrote for me legislation that gradually decontrolled oil prices,” wrote Krueger in a 2003 op-ed piece in the Chronicle. “Throughout this period, Bill was my mentor.” Krueger’s bills did not pass, but no one forgot White’s contributions, which were written up in the New York Times. In 1978 he was back, taking a temporary leave from law school and helping Krueger, who was at that time floor manager for a natural gas deregulation bill. “I recall going up to D.C. and being one office off the House floor as floor amendments were coming in,” White says now. “It was very exciting. I kept up with it over the years.”

At the Department of Energy, White spearheaded American efforts to make parts of the former Soviet Union available to oil and gas drilling. “During Clinton’s first term, Bill was one of the key players in bringing U.S. support to constructing a regionally strategic oil and gas pipeline from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean,” says Steve Nican-dros, the chairman and CEO of Frontera Resources, a company that White helped create. White hobnobbed with heads of state such as President Eduard Shevardnadze, of Georgia, and President Heydar Aliyev, of Azerbaijan. He helped close the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine. He undertook major reforms in the DOE, opening up more than $27 billion in contracts to competition for the first time and cutting the department’s workforce by 3,788 employees on a five-year plan. When he left the job, in July 1995, to become more involved in state politics, the Washington Post ran a flattering story under the headline “Government Loses a Key Reinventor.”

Back in Texas, White found that he was very much in demand. In a state where energy is one of the main drivers of the economy, holding the number two job at the DOE carried enormous weight. White capitalized on it right away, first by becoming head of the Texas Democratic Party and then by starting Frontera Resources, part of whose mission was an extension of what White had been doing at the DOE: looking for exploration and production opportunities in far eastern Europe. He assembled a dazzling, high-powered group of co-founders and investors that included former senator and Secretary of the Treasury Lloyd Bentsen and his son Lan, a finance and real estate executive; former Conoco chairman Constantine “Dino” Nicandros; his son, Steve, the former head of Conoco Overseas Oil; and Houston venture capitalist J. Livingston Kosberg. Former CIA director John Deutch was briefly an adviser. There were plenty of other blue-chip investors as well, including Baker Hughes, Shell Capital, Deutsche Bank, Schlumberger, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. This, of course, was where White’s political connections would come into play. Though White had helped fund Frontera’s early existence from his own pocket, he had a short-lived executive role, partly because he was spending most of his time traveling around the state trying to revive the moribund Democratic party. Frontera was simply a very ambitious side project for him. He became chairman; Steve Nicandros ran the company. All in all, it was a remarkable play, and it had been entirely Bill White’s idea.

Incorporated in 1996, the high-flying, politically connected Frontera became one of the first Western companies in Azerbaijan to have an onshore production—sharing agreement. Fueled by a $60 million loan from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the company ramped up production to approximately six thousand barrels of oil a day and was making money within three years. “Then we hit a speed bump,” says Steve Nicandros. “The Azeri state oil company changed the rules.” One of the company’s primary lenders bailed out, which forced Frontera to sell its assets in Azerbaijan and redistribute them in the neighboring country of Georgia, a major blow for its backers. (It is not known how much White invested; his former boss Steve Susman invested $1 million, and it is probably safe to assume that White invested at least that much.)

Though one of White’s opponents in the 2003 mayoral race portrayed Frontera as a failure, the truth is more nuanced. White himself had nothing to do with Frontera’s board or its management after 2001. Eventually Frontera went public and has focused its exploration efforts primarily in Georgia. Though it has not seen profits in recent years—its stock has fallen from a high of $2.87 to 25 cents—the company remains well funded, pursuing potentially lucrative oil and gas business.

The reason White shifted his attention away from the company was that his burgeoning career had taken yet another turn: In 1997 he had been named the president and CEO of the Wedge Group, a Houston-based holding company for energy, manufacturing, real estate, hotel, and other interests, with approximately $200 million in revenues, owned by then—Lebanese deputy prime minister Issam Fares. Its business was acquiring firms, running them and fixing them up, then selling them at a profit. White proved an able executive; in the years after he took over, the company saw an 80 percent annualized return on its assets. White made millions. He held board meetings in Monaco. He spent time in Spain learning Spanish, which was not an idle hobby. White, who calculates many moves ahead and many years into the future, was thinking about politics again. In 2003 he spent $2.2 million of his own money, leaned on his business friends to raise a record $8.6 million, and came out of nowhere to win the mayor’s race against veteran Houston politicians Sylvester Turner and Orlando Sanchez.

Though he is a lifelong Democrat, White is not an ideologue. He is a resolute pragmatist, a problem solver, a man who sees the world as a succession of challenges, great and small, that can be resolved by the application of old-fashioned horse sense, fair play, and raw intelligence. It is a strikingly simple, binary vision. That is not to say that White is inflexible; he is famous for compromise, because he believes that consensus is the intelligent way to govern. He is disappointed when his city council votes are not unanimous, because he works hard at accommodating the members, and such a vote amounts to a challenge to his sense of the rightness of things, to his conviction that smart and sensible people will automatically see and appreciate good ideas. “I want the city council to realize that they are my partners in governing the city,” he says. “The people in Houston want a safer city, they want jobs, they want it to be easier to get around, they want amenities like parks and libraries, and they don’t want to pay more than they have to in property taxes. These are goals we share in common. If somebody has a better way of approaching that goal, we ought to listen. But if somebody is doing something for a reason that is not factual or based on a mistake, then we ought to correct the mistake.”

This is the way White talks. Behind his pragmatism stands a stern view of morality that is never far from the surface. Once one of his acquaintances, who had raised a good deal of money for the police department, sent White a speeding ticket he had received, assuming White would fix it. White sent it back with a note asking if the man would like his contributions refunded. Likewise, he bridles at the notion that politics could possibly influence the awarding of city contracts. Early in his administration, when he heard that a Wall Street firm that did business with the city had retained a prominent political fund-raiser, he publicly criticized the company, lecturing it on civic morality and making it clear, as he says, that such a firm “was not on the program of my administration . . .

What I don’t like is the influence of money on politics.”

One of White’s early triumphs—and a classic example of how he operates—was his untangling of the city’s finances. White is good with numbers. He finds reading spreadsheets late at night relaxing. Two years before he was even elected mayor, he had volunteered to help the city, which was running short of money to pay for parks and libraries. Within a few months he had restructured the repayment of city bonds in such a way that he freed $80 million for parks and $40 million for libraries, with no tax increase. City officials, who were getting what seemed to be free money, were amazed. “I don’t think I am a stranger to public finance,” Houston’s chief administrative officer Al Haines told the Chronicle at the time, “but this was like going back to school. Bill really immersed himself in this.”

His skills became apparent in the early months of his administration in 2004, when White discovered what amounted to a time bomb embedded in the municipal pension system. The city, as it turned out, had accidentally been too generous. The pension board had originally estimated that funding the pension plan would consume about 15 percent of the total payroll for this group. White figured out that the pension fund was going to eat an astonishing 52 percent of the payroll. His subsequent retooling of the pension system—which included passing a citywide referendum—was one of his first successes as mayor.

“I have not seen a mayor get involved in that much financial detail,” says Judy Gray Johnson, a former Houston city comptroller and former city director of finance and administration. “He wanted to know every decision that was made that affected finances not just for the immediate impact but for what would happen over a five-year period. I learned very quickly that I could never give him a number that wasn’t solid and I could never fudge because he would remember everything.” In lockstep with the mayor was his fourteen-member council, which gave him comfortable majorities on most of the city’s key issues. “His style of leadership is one of collaboration and thoughtfulness and attention to detail,” says council member Clutterbuck, a Republican who, like several other Republicans on the council, chairs an important committee (in her case, Budget and Fiscal Affairs). “He is frankly one of the reasons I chose to run for office. I wanted to be part of working with that leadership style.”

Through it all he was his calm, persistent self in public, while making often brutal demands on his staff. White is in fact obsessive about work, sleeping just a few hours a night and spending very little time doing anything else. His wife and three children are all volunteering for his Senate campaign. “He is hard on himself and very demanding of others,” says Bob Stein, a professor of political science at Rice who has worked with White on various issues on a pro bono basis. “If you fail Bill, you are pretty much out of favor.”

It is this résumé that drives White’s campaign for the Senate. He has so much to talk about, so many victories to boast of, so few enemies and critics, that he can sometimes seem a bit unreal. Too machinelike, perhaps. And it is true that you have to go looking hard to find much that is truly negative about his six-year tenure as mayor. His success, from Katrina forward and including an equally impressive performance in helping the city recover from Hurricane Ike in 2008, has mostly silenced his opposition. In the race to replace him as mayor this year, no candidate uttered a bad word about Bill White.

There is no such immunity in the Senate race, where the opposition’s big guns are already trained on him. After governing a city in a bipartisan way, he is suddenly vulnerable simply because he is a Democrat in a red state where Obama’s fragile popularity is already waning. In September he came under pointed attack by the Republican National Senatorial Committee, which claimed he supported Obama’s cap and trade system to limit carbon dioxide emissions, saying it would lead to “higher energy costs, increased taxes, and a loss in jobs.” He is pilloried in the blogosphere for his advocacy of Houston as a “sanctuary city,” meaning a place where the police do not question people about their immigrant status.

His opponents are also starting to focus on his three terms as mayor. He has not made many political mistakes, but with a record as clean as White’s, they tend to stand out. In September 2004, White appeared at a fundraiser for then—House majority leader Tom DeLay, of Sugar Land. Though this was before DeLay was officially admonished by the House Ethics Committee, it was after a Houston area congressman, Democrat Chris Bell, had filed an ethics complaint against him. White had also appointed DeLay’s former top aide Ann Travis as his chief of governmental affairs.

“I think Bill believed he had to work with DeLay to get urban rail,” says Bell, who now works as a lawyer in Houston. “But a lot of us felt it went too far. I had just filed the ethics complaint against DeLay when I learned that the mayor was going to be a special guest at a fundraiser for him. Later Bill appeared in a video tribute for DeLay. It didn’t sit well.”

Then there are some minor political sins that will no doubt also resurface in the coming months. In January White wrote a letter on behalf of developer Marvy Finger asking Houstonians to consider renting in his new One Park Place tower, a building rising above Discovery Green, one of White’s proudest accomplishments. White was promoting his pet project and the crown jewel of his program to increase urban parkland, but “exhorting Houstonians,” as the Chronicle put it, to rent from a private commercial developer was out of keeping with the White administration’s strict intolerance of cronyism and insider deals. Another apparent lapse in judgment was a political ad that ran the same month in the Houston Defender, a newspaper serving the black community. It featured pictures of White, Martin Luther King Jr., and Obama, with the words “The Hope [White], The Dream [King] and The Change [Obama].” The ad, which seemed to many to equate White with King, caused a minor uproar among some community activists. Though it was produced by the Defender’s staff, it was paid for by the White campaign. He angered conservatives and property rights advocates—and even his friend Bob Lanier—when he loudly vowed to stop a high-rise apartment building that was going up near leafy, residential West University Place. Since then, White has engineered what the group that opposed him most strongly, Houstonians for Responsible Growth, now calls “a reasonable balance between neighborhood concerns and the market-driven growth that has made possible our affordable home prices.” Still, opponents on the right may well use this against him too.

White, meanwhile, is moving ahead, traveling the state on weekends in his rented jet, touting his record as mayor. With his virtually built-in capacity to carry Harris County, the state’s most populous; his ability to raise enormous sums of money from both Democrats and Republicans; and his deep Rolodex of friends and party regulars from his days as chair of the Texas Democratic Party, he is already clearly among the front-runners for Hutchison’s Senate seat. He will need that cash to sell himself to the rest of the state, which doesn’t know him yet and may find him, as Houstonians once did, somewhat less than spectacular.

Shortly before he was elected to his first term, White was riding with his friend, the renewable-energy executive Michael Zilkha, when he fell off his bicycle and broke his collarbone. “I drove him to Methodist Hospital,” says Zilkha, “and when he went into the emergency room, no one recognized him, even though he was on the board of the hospital. That would never happen today.”

Indeed it would not. White’s transformation from a complete unknown to a household name in Houston in the space of six short years is a reminder of how fast things can change in Texas politics. He can only hope that the rest of the state catches on as quickly, instead of dismissing him as the latest long-shot Democrat who is convinced he can break through the Republican tide.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Rick Perry

- Bill White