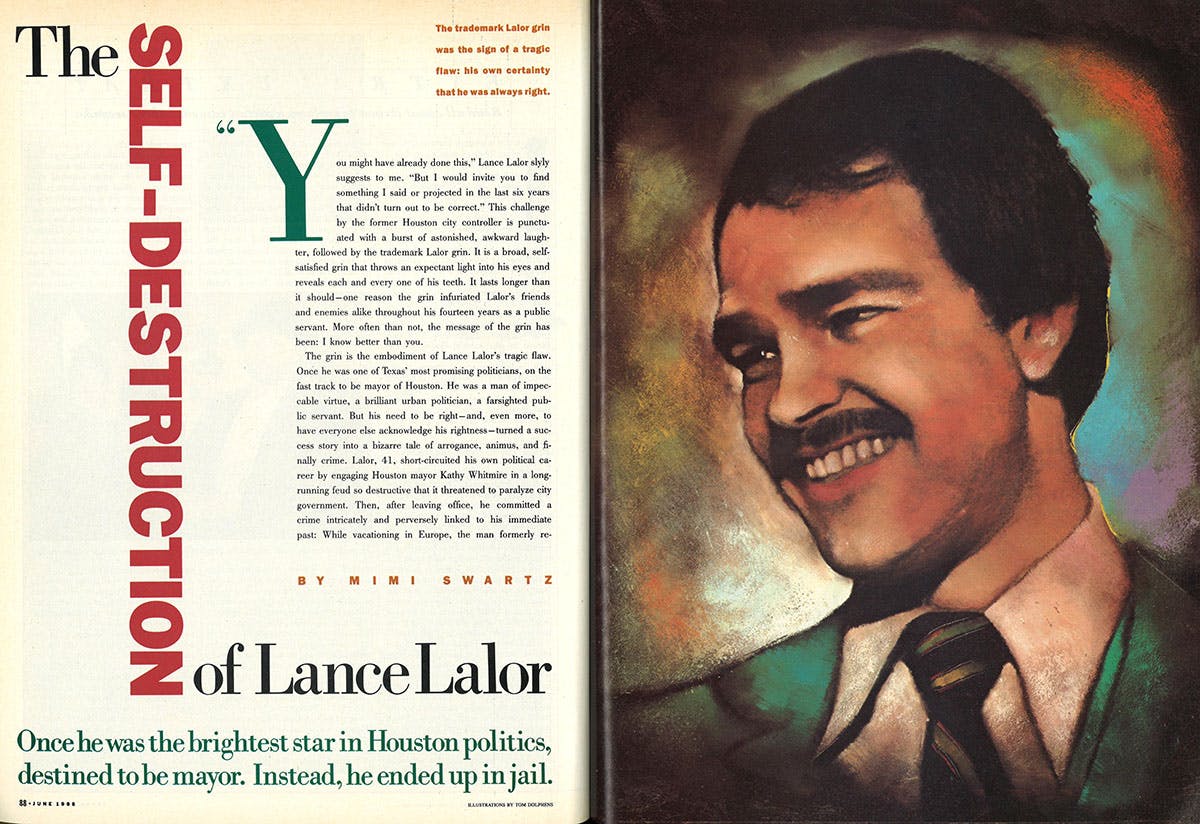

You might have already done this,” Lance Lalor slyly suggests to me. “But I would invite you to find something I said or projected in the last six years that didn’t turn out to be correct.” This challenge by the former Houston city controller is punctuated with a burst of astonished, awkward laughter, followed by the trademark Lalor grin. It is a broad, self- satisfied grin that throws an expectant fight into his eyes and reveals each and every one of his teeth. It lasts longer than it should—one reason the grin infuriated Lalor’s friends and enemies alike throughout his fourteen years as a public servant. More often than not, the message of the grin has been: I know better than you.

The grin is the embodiment of Lance Lalor’s tragic flaw. Once he was one of Texas’ most promising politicians, on the fast track to be mayor of Houston. He was a man of impeccable virtue, a brilliant urban politician, a farsighted public servant. But his need to be right—and, even more, to have everyone else acknowledge his rightness—turned a success story into a bizarre tale of arrogance, animus, and finally crime. Lalor, 41, short-circuited his own political career by engaging Houston mayor Kathy Whitmire in a long-running feud so destructive that it threatened to paralyze city government. Then, after leaving office, he committed a crime intricately and perversely linked to his immediate past: While vacationing in Europe, the man formerly responsible for Houston’s financial integrity was arrested for using a stolen credit card to pay for meals totaling $113. Even stranger, Lalor’s girlfriend turned him in. Charged with possession of a stolen credit card and intent to deceive, Lalor was fined about $250 for committing what is a third-degree felony in Texas.

That past, however, is not readily apparent on this spring day in Houston, when the humidity is just beginning to tip its hand. Lalor glides from his powder-blue Jaguar to a seat in a tiny restaurant with the swift, efficient step of the manager of a very fine hotel. He is excruciatingly groomed, from his monogrammed cuffs—LL’s in elaborate script—to his blue blazer, which clings desperately to his flawless physique. This is not a man likely to accept the premise that his life went sadly and strangely awry. Lalor maintains that he is only too happy to be rid of politics, that any suggestion of thwarted ambition is based on “an improper premise,” that nothing in his six-year term as controller would “conduce to that end.”

You’d almost think he has put the bad times behind him. Lalor says he has a new job now, as a consultant to an international-aid organization. But as he speaks, his long fingers flutter anxiously through the air and then stiffen, slicing to stress his points, and the discussion shifts into a diatribe. As Lalor’s voice careens on and on in hushed, clipped tones, he fails to meet my gaze, so that it appears he is talking to himself most of all. The Houston press, with whom he fought constantly, writes “the silliest, stupidest stories and nobody cares.” Of his nemesis, Kathy Whitmire, he says, “To this day I don’t think Kathy is personally venal, but she tolerates it around her.” On politics in general—the field in which he spent more than six years as a campaign operative, four years as a state legislator, and two years as a city councilman before becoming controller—Lalor’s final assessment is that “the only way you run for higher office is by sucking up to contributors, the media, and interest groups.” When asked about the incident in London—to which he pleaded guilty and paid his fine—Lalor spins away from the table like a car swerving to avoid a collision. Then he says, “I was not involved in the credit card thing. I was just there. I was a bystander.” In a short time, a different Lalor has emerged, someone as fragile as he is destructive, someone who has forgotten and forgiven nothing, someone with a powerful need to diminish and despoil the world he was once so proudly a member of.

It could be said that Lance Lalor’s story reveals the profound impact personality has on politics, that it serves as an object lesson for the limitations of operating on intelligence alone, of the perils of the moral-watchdog role Lalor chose for himself. Lalor’s story is also a way to understand Houston’s decline, to discover one reason why the city has been unable to cope with the budget crises that have become such regular occurrences. But there is something more universal about Lalor’s story and something more haunting: Lalor can blame everyone else for his failure to succeed, but like many tragic figures, the final responsibility is his own. To find the path that led a young man with a promising future to such a destructive end is to understand what happens when the imperatives of character’ collide with the specifics of circumstance. At that point, Lalor’s intense need to be right caused his well-planned life to go tragically wrong.

The Charges in Question

The last thing anyone would have imagined was that Lance Lalor would wind up with his photograph on the Houston Post’s front page under a headline like LALOR HELD BEHIND BARS IN LONDON. Or that he would be the butt of jokes (“Lalor should have left home without it”), a source of derision (one Houston restaurant made a welcome-home banner for him out of American Express receipts). He had a reputation for many things—abrasiveness, elusiveness, eccentricity—but mostly he had a reputation for integrity and for attacking those who lacked it.

Yet as of January, he joined the club of the seriously flawed. The facts from witnesses and police reports are these: On December 31, two days before his successor was sworn in, Lalor set off for a two-week tour of the British Isles with his girlfriend, Kathy Cole. Cole, 34, a tall, blond, prom-queen-pretty divorcee, had invited Lalor to go along and had paid for the hotels and airfare in advance. But on January 1, Lalor used the credit card of a man named Wade Bartlett to pay for a $72 dinner at an Italian restaurant in London. The next evening Lalor again used Bartlett’s card at the Mandarin Chinese restaurant in Kensington. The manager of the restaurant ran the card through the standard authorization check, but there was a delay. When notified of the wait, in the words of one waiter, “they threw some money on the table and ran away.”

The next day Cole called the restaurant and learned that Bartlett’s name was on the card. Concerned about being implicated, Cole contacted the London police. Along with the information that her companion was using a stolen credit card, Cole told them that he had been acting strangely—she implied that he intended to change his identity and hinted that he had been obsessed with an airline bombing that had occurred several months before. Then she returned to Houston alone. Lalor was arrested shortly thereafter at Gatwick airport. In addition to the two illegal transactions in London, a third turned up—the card had been used to charge $40 worth of books at the British Travel Bookshop in New York. On January 29 Lalor was tried in a London court for possession of a stolen credit card and intent to deceive. He confessed to using the card twice and was fined about $250 and given a conditional sentence. All charges will be dismissed after a twelve-month probation period. The judge was a stranger to Houston politics, but he used a word frequently leveled at Lalor at city hall: he called the case “bizarre.” “It is not at all clear to me why a person of your standing should attempt to use the card in this manner,” the judge told Lalor. “This is the most extraordinary tale.” He wondered why the couple behaved so absurdly. “Was it some sort of game?” he asked. As was so often true with Lalor, the answers were not apparent on the surface, but lay buried—not just in the past, but in the mysteries of his complicated nature.

The Making of a Reformer

From his earliest days, two traits dominate Lance Lalor’s life: an overriding intelligence (“bright beyond belief” is the way one council member described it) and a scorn for convention. Lalor, the oldest of six children, was born to a family of modest circumstances—his father was a paint salesman, his mother worked at Foley’s—in the Houston suburb of Bellaire. He rebelled against his conventional surroundings from the start. Faced with a ten-page assignment in high school, for instance, Lalor would turn in a paper five times as long three days late—and get away with it because his work was exceptional.

In the late sixties at Harvard Law School, he became an instant legend when he refused to take the final examination in property. Lalor read through the test and announced to the class that it wasn’t worth taking. Once again Lalor broke the rules and got away with it—the professor let him take the test later. “He always had a clever way of flouting authority,” a high school classmate recalls.

He was drawn inexorably to public affairs. In high school he distinguished himself in debate and extemporaneous speaking. In college, majoring in political science and art history at Tulane, the sardonic young man found a purpose that would shape his life—civil rights. It was an issue where right and wrong were clearly defined, where there was no need for the compromises that he would find so thorny in the future. Lalor registered voters, tutored ghetto kids, and picked cotton in the fields of the Mississippi Delta. But the work he liked best was organizing campaigns. “I got into politics to get establishment candidates out,” he says.

In one of his earliest successes, Lalor helped Charles Evers become the mayor of Fayette, Mississippi, a black-majority town that had never had anything but white officials. The winners reached city hall only to find it cleaned out—no books, no records, no nothing. With another activist, Lalor holed up in the Natchez library and taught himself how to run a town. He must have found the power of rules there; his understanding of charters, ordinances, and procedures would later give him an advantage over his opponents. Lalor got to do what he could never do in Houston—build the ideal city hall, one free of the bureaucrats and favor-seekers who would plague him later.

Ultimately, law school took a back seat to politics. Lalor quit Harvard in 1971, one course short of a degree. Sometimes he told friends that his notes for a paper had been stolen and that he didn’t have the inclination to start over; sometimes he told them that he found out he didn’t like lawyers. Either way, his explanation was true to form. When Lalor didn’t want to do something anymore, he made it into something not worth doing.

Lalor returned to Houston in 1973 to work on Fred Hofheinz’s race for mayor. Only 27, Lalor was a campaign veteran by this time, having worked in Father Robert F. Drinan’s upset victory in the 1970 Massachusetts congressional race and for George McGovern in 1972 under Gary Hart. The Hofheinz race was exactly the kind that had attracted Lalor to politics—a battle of insurgent minorities, liberals, and young professionals against the old guard. Hofheinz hands remember Lalor as a master of detail; he could predict the vote totals in sections of the city within a percentage point, and he knew not only which telephone poles should have posters but how many staples to use. But another Lalor trait that would later become maddeningly familiar made its appearance. He had been a fixture around the campaign headquarters, but in the hiatus between the first election and the runoff, he disappeared. After he didn’t turn up for several days, a staffer finally went by his house—then as now Lalor operated without a telephone. The staffer left a note, and Lalor showed up in time to help with the runoff. But when he went back, according to another campaign worker, “he made it clear that he was independent and didn’t really like anybody there.” Sharing—even sharing victory—was not his style.

In 1976, after serving as an aide to Hofheinz for two years, he won a seat in the Texas House of Representatives. Just thirty years old, Lalor was street smart and shrewd. He suffered from none of the insecurity that plagued other freshmen. He always seemed to know where the bodies were buried—a girlfriend in the Speaker’s office and a wily staff couldn’t have hurt—but he was not out to make friends at the Capitol. Lalor cloaked himself in his integrity—returning lobbyists’ gifts, ever vigilant that his campaign contributions were properly documented. He had no other job; Lalor lived on his $7,200 salary.

He was, as before, tireless and meticulous—a lobbyist remembers receiving a call from Lalor at nine o’clock on a Sunday morning after he’d spotted a typo in a bill. More important, Lalor was a master of procedure. “Your bill has a fatal flaw,” Lalor once hissed in the ear of a designated victim and then, with his adversary on the ropes, extracted his concessions. When Lalor didn’t need the rules, he ignored them. He had no use for etiquette. When Speaker Bill Clayton once summoned the young legislator to his office, Lalor refused, suggesting that the Speaker come to him. Clayton did.

Not that Lalor’s abrasiveness cost him. His agenda—funding for urban parks and the arts; support of ethics, consumer, and government-efficiency legislation—made him the darling of young urban liberals. His real interest, however, was city rather than state government, and after two legislative terms he ran for the Houston City Council in 1979. He beat thirteen other candidates to claim his seat.

Lalor’s city council experience mirrored his years in the Legislature. As part of the first council elected from single-member districts, he joined a new wave of local politicians who had their own ideas and programs, who weren’t simply there to rubber-stamp the mayor’s proposals. Lalor settled into his familiar routine, working his standard eighteen-hour days and separating himself from the pack. By nearly all accounts, he was a brilliant councilman. He introduced a budget-review process where none had existed before, wrote the city’s first piece of billboard legislation, took on unscrupulous tow-truck drivers, worked for gay rights. He remained true to his reformer’s ideals.

Once again, Lalor made few friends. To him, there was no such thing as a small affront. Lalor swiftly ended a longtime friendship with councilwoman Eleanor Tinsley after she accidentally betrayed a confidence in an open council meeting. Subsequently, he wouldn’t even share the same city hall elevator with her. (Stories of Lalor cutting off old friends and associates are legion, though he fails to recall them.)

Lalor reserved his harshest judgments for Mayor Jim McConn, a classic good ol’ boy and therefore anathema to Lalor. When the mayor was implicated in a scandal over the awarding of lucrative cable TV franchises, the councilman stepped up his attacks; he even showed up at one of McConn’s reelection fundraisers and told everyone he hadn’t wanted to miss the mayor’s retirement party. If it made sense philosophically for Lalor to attack the mayor, it made sense politically too; by 1980 it was conventional wisdom that Lalor would one day have McConn’s job. The problem was finding the next step up the ladder. He vacillated between going to business school and running for city controller, finally choosing the latter. He made no secret of his ambitions. “I ruled out long ago running for a state office or a federal office,” Lalor told the press when he announced his intention to run. “My sole interest is in local government, and I can’t conceive of ever running for any other office except possibly mayor.” Four years would be his limit, he promised. Lalor no doubt assumed that he wouldn’t have to wait that long for McConn to quit and leave him as heir apparent. But retiring controller Kathy Whitmire upset McConn to claim the mayor’s office in 1981. Still, it seemed unlikely that Whitmire could get in the way of someone as brilliant and talented as Lance Lalor.

Promises to Keep

“When I ran for controller, I was very specific. I said I was not going to be like my predecessors,” Lance Lalor explains, ticking off on his fingers the ways in which he was not like former controllers Whitmire and Leonel Castillo. They were “hacks” who, unlike him, “did not have the best interests of the city at heart.”

“I said I was not going to run for political office, I was not going to grandstand, I was not going to put out press releases, I was not going to hold press conferences.” As Lalor falls into this familiar litany, his face contorts with concentration, and his voice takes on a familiar urgency: “When I ran for controller I got out of politics, and not only did I say I was getting out of politics, but it was true. I didn’t go to political events; I haven’t been to rodeo parades or ribbon cuttings. I never sucked up to interest groups—none of that for more than six years.”

What in Lalor’s eyes was his greatest success was in reality his greatest failure. At a time when he most needed to be a good politician—to build coalitions, say—Lalor chose instead to withdraw and to alienate. The visionary had a vision problem; politicians need allies, not just to get reelected but to accomplish their goals. Because Lalor couldn’t be flexible—he couldn’t break with his reformer-loner role—he put himself on a course that led directly to his political self-destruction.

Lalor had misjudged his future. Far from being a stepping-stone to the mayor’s office, the controller’s job was particularly ill suited to his talents. While he had a good head for numbers—and was famous for being tight—he was leaving the world of ideas for the world of administration. He also lost the humanizing element of constituent contact, the call from the man on the street who wants a broken traffic light fixed. What he gained was the second-most-important job in Houston, which, considering Houston’s strong- mayor system—and Whitmire’s legendary stubbornness—was a very distant second on the power scale. The controller’s job is, at its heart, a bookkeeper’s position; he has the power to apply the brake if spending gets out of hand, but he has few chances to dispense favors and build a base of his own. The only way the controller can get his programs through—or oppose the mayor’s—is to build and maintain strong ties to the press, the power structure, the council, and the public. Lalor deliberately cut them off.

His first move was to disappear. The councilman who had so often basked in the limelight abruptly buried himself in his work for the first nine months, prompting the Houston Chronicle to ask in an editorial, Where Is Lance Lalor? While teaching himself his new job, however, Lalor made a startling discovery: he detected a drop in sales-tax collections. In the short run, that meant there would be less money for Houston to budget during the next fiscal year; over the long haul, that meant Houston’s salad days were over.

Understandably, that was not news anyone wanted to hear around city hall, where optimistic financial projections are the rule. Lalor sent a series of memos to the mayor. Whitmire didn’t respond. Lalor’s memos became more frequent and more vitriolic. Finally, late in 1982, Lalor told the mayor and the council that he would impose spending controls unless they could all agree on how much money Houston would be able to spend in the coming year. Word leaked to the press, infuriating the mayor. Meanwhile Lalor, ever a student of the rules, had studied the city charter and implemented a power controllers seldom used. To control spending, he demanded the council and the mayor get his signature authorizing that money was available for each item they wanted to include in the budget. Lalor may have believed he was just doing his job, but Whitmire had a different idea—that Lalor wanted veto power over the budget. She threatened to take him to court.

If Lalor and Whitmire had been different people, things might not have deteriorated so quickly. Whitmire and McConn had had celebrated fights, but at least McConn knew how to cut a deal. Neither Whitmire nor Lalor did. Lalor was then a dashing, dark-haired rebel while Whitmire, before her makeover, was a frumpy blonde with big glasses and severe suits. But it was and is commonly held that no two people were more alike. Both were unmarried with nothing in their lives but a single-minded dedication to city government; both could be stubborn, abrasive, vindictive, and thin-skinned when everything was on the line, which was always. There was only one difference that really mattered: “Lalor is smarter,” says one former city-hall staffer, “but Whitmire is more determined.”

As usual, Lalor wasted no time in putting his reformer’s stamp on his new job. He saved money by consolidating the city’s 184 bank accounts and earned millions by eliminating idle deposits in accounts at Texas Commerce Bank, requiring banks instead to bid for the city’s deposits. Accounting firms wanting to serve as the city’s outside auditors also had to submit competitive bids. Lalor replaced political operatives with professionals and uncovered financial abuses by Whitmire appointees.

It was inevitable that he would clash with his predecessor, and the nature of the battle was established early: Lalor would accuse Whitmire of being financially irresponsible; she would accuse him of being bizarre and erratic. Whitmire told the Post Lalor had the personality of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; Lalor retaliated by saying that Houston’s strong-mayor form of government “doesn’t have to be a dictatorship.” The crucial financial issues at stake—how to keep the city running and growing with ever-shrinking financial resources—were soon lost in a barrage of public name-calling. Even worse, the two most powerful public officials in Houston would not speak to each other.

When Whitmire needed to speak to Lalor, she contacted Councilman John Goodner, who acted as intermediary. His perception was that Lalor was angry because the mayor wouldn’t answer his memos and that the mayor was angry because Lalor wouldn’t return her phone calls. Considering Lalor’s gift for nasty prose (“Your note was the sort of gutless weasel-like double talk which has characterized your behavior in the last month”) and hers for tongue-lashings, the schism was hardly surprising. After several peacemaking sessions—during one, Lalor sat in a chair and recited the mayor’s sins—the two agreed to meet for breakfast once a week. The punctual Lalor showed up on time. Whitmire arrived late, often after Lalor had left in disgust.

Any ally of the mayor’s became an enemy of Lalor’s. When the personnel department questioned raises in the controller’s office, Lalor held up the paychecks of personnel employees. When city attorney Hank Coleman sided with Whitmire in a dispute, he too became a recipient of Lalor’s nasty memos; eventually, Lalor stopped speaking to Coleman.

Almost lost in the rancor was the outcome of Lalor’s battle to exercise control over spending. After years of squabbling, he won; Whitmire and the council agreed to abide by Lalor’s revenue estimates when setting the budget. But victory did not temper Lalor’s contentiousness. It wasn’t just the mayor who felt the controller’s wrath; it was anyone who crossed him. His good press relations soured after Lalor sent his press assistant to inform two Post reporters that henceforth they should submit their questions in writing. Lalor became more and more elusive with the press; he was hard to find and even harder to pin down. He called two reporters “scurrilous scumbags.” Others received long, hectoring memos on the controller’s letterhead but always unsigned. After the Post’s Tom Kennedy wrote a column critical of Lalor (Lalor’s Jekyll-to-Hyde Roles Baffling), the controller went on a radio show to denounce the reporter as a mouthpiece for the mayor, maybe even insinuating something sexual by suggesting Kennedy “swam in the mayor’s pool.” In a later column (Lalor Productive, Surly and Vindictive) Kennedy explained that he had attended one of Whitmire’s poolside cocktail parties with his wife.

There was almost always method in Lalor’s madness—a program he opposed, a punishment he was extracting—but neutrals lacked the inclination to detect it. Times were hard in Houston —in 1984 the city had lost its treasured AAA bond rating, money was scarcer than ever, and services were deteriorating. The city needed compromise but was getting conflict instead. By 1986 Lalor was even sniping at Whitmire in the city’s annual financial report, filling the pages with dark hints of “departures from general accounting principles” and “possible malfeasances.” He may have been right about some of Whitmire’s financing schemes—dipping deeply into reserves, for example—but he had worn people, too many people, down. The war of words was taking its toll on Lalor too. He announced his re-election bid in 1983 but ruled out running for higher office in the future. The onetime campaign strategist did not campaign, and a Lyndon Larouche candidate who advocated a crash program to develop laser-beam weapons in space got 26 percent of the vote.

The Battle of the Bonds

In the summer of 1985 Lalor launched the climactic battle of his career—an attempt to take control of city bond sales, the multimillion-dollar deals that finance projects from sewer lines to convention centers. As usual, Lalor had reason for concern. Whitmire and the council believed post-bust Houston was in need of a massive capital-improvement program; with the tax base shrinking, they began borrowing at an unprecedented rate. But among the beneficiaries of that policy were the bond lawyers, investment bankers, and financial advisers who championed the idea of using bonds, assembled the deals, and charged the city lucrative fees—the kind of establishment back-scratching that Lalor would not tolerate. He was incensed when an old adversary, city attorney Hank Coleman, returned to private practice at Vinson and Elkins and immediately began representing the city as bond counsel.

Lalor believed that the city charter gave him authority to control bond issues. In fact, the charter is vague on the point; it puts the controller in charge of the city’s fiscal affairs, but exactly what that involves is not spelled out. McConn and Whitmire had had their disagreements, but they found a way to work together. Whitmire wouldn’t relinquish power to Lalor, even though in at least one meeting several trusted advisers told her that Lalor was the official who was most capable of handling the duties.

By that time in Lalor’s tenure, it hardly mattered that he was right that the city could save money by putting him in charge of bond sales. His tactics had alienated almost everyone. Outside financial advisers who had been impressed with Lalor’s expertise resented that he would withhold his signature from contracts until the work was done—and then negotiate their fees downward. Granted, his hard bargaining provided some savings, but the companies usually found other ways to make up the difference. Even the few council members who still supported him were put off when Lalor—after cooperating with Whitmire’s staff to prepare a sewer-bond issue and never hinting at his disapproval—denounced it to the council on the day it came up for a vote. The council approved the package over his objections, and Whitmire began to cut him out of future negotiations.

It was getting ridiculous. Lalor refused to attend meetings on bond issues unless he chaired them—his right, he insisted, as the city’s chief financial officer. Soon he barred his employees from attending as well. The city was drawn into an unfortunate pattern: Often provoked by the administration, Lalor would refuse to be involved in meetings and then would approve the sale only after creating a crisis. In October 1986 Lalor went on the offensive again. Condemning previous bond issues as “notorious and embarrassing,” Lalor asked the council to formally grant him authority to coordinate all bond sales.

If ever there was a time for Lalor to try to mend his fences, this was it. Millions of dollars, not to mention his reputation and an important matter of principle, were at stake. Instead, Lalor stepped up his fighting on other fronts. Earlier, in July, Lalor was the only elected official who refused to take a 3 percent pay cut. In an editorial cartoon, the Post portrayed him as a baby with a pacifier in his mouth. In October 1986 he refused to include the traditional letter from outside auditors with Houston’s annual financial report; because the auditors were under contract to the mayor, Lalor said, they could not be trusted. When Whitmire asked him to reissue the report with the letter included, Lalor shot back another memo. The auditors’ firm, he wrote, was willing to “ignore its own ethical guidelines in order to conspire with you to achieve your personal and political goals.” When the council asked Lalor to appear before it to explain his actions, he sent a message that he preferred not to. He would fight on alone.

Lalor was showing signs of combat fatigue. The reformer could not cope with the constant need to compromise; the politician used to victory could not face the cold grip of failure. During a heated argument, Lalor grabbed the mayor’s chief of finance and administration by the necktie, and he also shoved a diminutive financial adviser after she said something he disagreed with. The man who had once treasured his staff was now removing notices of parties for departing staffers from the office bulletin board. More and more, Lalor was perceived as a man who was saying no just to exercise what little power he had left—any sense of mission had been lost. When Councilman John Goodner went to Lalor’s office one day during the height of the bond battle, he found the controller with his head in his hands, considering resignation. “Toward the end,” says a former Lalor staffer, “you had to wonder if he had both oars in the water.”

Finally—with the mayor and Lalor once more threatening to take each other to court over the control of a $160 million sewer-bond sale in December—the council had enough. It voted unanimously that the two find a way to cooperate. Subsequent mediation gave Lalor authority to review bond deals after they had been assembled, and he usually approved them. But that did not assuage his distrust of the administration. Lalor made an accusation that his signature was being forged on bond documents. The forged signature was a standard facsimile used to position signatures on the bond proofs for printing.

Lalor’s erratic behavior and utter disregard for political convention turned what should have been a winning position into a losing one. In March 1987 the council voted 9-6 to give the mayor control of bond sales, allowing her to take charge with the help of hired financial advisers. It was the worst possible outcome; because Lalor could not be trusted, more of the city’s business would be placed in private hands. Lalor fought on, of course. He called the mayor a “debt addict” and vowed to boycott an upcoming bond sale. Each time the mayor tried to bypass Lalor, he found ways to hold up the sale. The council searched for a compromise, but Lalor did not make it easy. Stung by the council’s vote against him, he refused to appear at meetings.

In June Councilman Jim Greenwood came up with a solution. The mayor’s financial consultants were replaced by a council group chosen by the mayor and the controller. The mayor would chair the meetings; if she was absent, the controller would run them. Whitmire agreed never to show up. By then, however, Lalor was withdrawing; as the November 1987 elections approached, he seemed to abdicate. He wouldn’t say whether he planned to run for reelection, though he made a halfhearted attempt to pick a successor. He abandoned that idea when Councilman George Greanias, a strong candidate, entered the race. He made no retirement announcement; he simply failed to file by the deadline. Lalor’s staff took the brunt of his disappointment. Determining that the job-performance reviews for some of his employees were too positive, Lalor rewrote them. The term he used over and over again was “abysmal failure.”

There was no transition. Greanias had to leave his belongings in boxes while he waited for Lalor to vacate. In the final hours, Lalor vanished before the secretaries could say good-bye.

Signing Off

Free of the identity he had bound himself to for his entire adult life, Lalor shaved off his moustache and told Cole he wanted to start fresh at the outset of the London trip. If Lalor was exhilarated, Cole was alarmed. She became even more worried when he pulled out an American Express Gold Card to pay for a meal at an Italian restaurant. Curious because she had previously seen him use only Diner’s Club or MasterCard, Cole quizzed Lalor, but he refused to respond. The next night, January 2, they had dinner at the Mandarin Chinese restaurant. According to Cole, who is backed by the recollection of a waitress, Lalor took out his wallet and presented Wade Bartlett’s card. In Cole’s version of the story, she questioned Lalor about his use of the card after they were detected, and finally, after Lalor abandoned her twice during the trip, Cole reported him to the police on January 9.

The story Lalor told the police is significantly different. He said that on November 1, while on a trip together to New York, Cole came back from a walk with an American Express Gold Card. The next day they used the card to buy travel books at a store not far from the British consulate. Once in England, according to his statement, Cole said, “Let’s see if this card will work in London.”

Lalor was repeating the pattern of his fights with Whitmire. He deflected blame by casting aspersions on someone else. He told a Chronicle reporter, for instance, that he had gone along with Cole to avoid a scene, that she had deep emotional problems. Cole retaliated by claiming that she had not been in New York when the card was first used and had the alibis to prove it. (Cole’s aunt and best friend both say she was in Houston; she also signed in at her Houston health club on the day Lalor said she was in New York.) Lalor then insinuated that Cole had authorization to use the card. It was as if the Houston city hall fight was still playing on Lalor’s mental stage; here he was, not a month after leaving office, haggling over a signature with a woman named Kathy again.

Cole and Lalor had been seeing each other for about a year, although their relationship had its limits. Cole never went to Lalor’s home the entire time they dated; indeed, she did not even know where he lived. (Former girlfriends describe the house as a lonely place with only the sparsest furnishings.) To Cole, Lalor seemed increasingly frustrated with his life; she says he told her countless times he wanted to leave Houston. His maverick’s streak both charmed and unnerved her. Once, as Cole was walking toward her car in her health club’s garage, Lalor, arriving, turned his Jaguar into an exit lane when he saw her. When she chided him, he kidded her that she would never get anywhere by following the rules.

Since the time he confessed to using the card in London, Lalor continues to blame Cole for the crime. At lunch with me, he says he knows of three times she used the card—“One of them was on the New York trip, and I know of two occasions in London”—and still maintains she had authorization to use the card. Wade Bartlett, the cardholder, denies that and denies knowing Lalor as well. A sales representative for a large corporation, Bartlett says he lost the card sometime after moving from Dallas to New York at the end of October. (He suspects he left it at the New York Delicatessen at Fifty-seventh Street and Sixth Avenue, the part of town Lalor prefers to stay in.)

As usual with Lalor, one gets drawn into the arguments and misses the point, which is that a man who prized his integrity wound up a forger. It may be, as one old friend suggests, that it was just a lark—free for the first time in his life, Lalor took a dip back into the youth he had forsaken so long ago. A darker theory holds that a man who never thought he should abide by traditional rules simply lost perspective and stepped over one more. There are also those who believe that it was only a matter of time before Lalor turned his destructiveness on himself; in his world of extremes, if he could not be perfect, then he would be deeply flawed. What is not plausible is that Lalor would get hoodwinked into a credit card scam. No one understood the power of a signature better than he—nearly every battle Lalor had fought for the past six years involved whether or not he would sign his name to an official document. With the forgery he showed everyone—including himself—just how little his years as controller had meant after all. In the process he spoiled the one thing he treasured above all else—his good name.

In the spring of 1988, Lance Lalor’s ghost hung over the city of Houston. He was said to be in town, he was said to be out of town. People said they saw him at traffic lights and that he sped off in his Jaguar to keep from being seen. The mayor, in her annual speech to the city, said the worst was over. Another budget crisis, complete with layoffs, followed. Certain shortfalls—in the municipal courts system, in the employee-health-benefits funds, for example—Lalor had predicted years before. He had been right, but he hadn’t been heard; council members remarked that they wished Lalor could have made them understand.

That may have been impossible. After our lunch, I had asked Lalor to call me so that I could check any additional information. The calls took on a familiar pattern: from phone booths in New York and Houston, Lalor would answer my questions and then tell me that I should be doing something more useful with my time. Inevitably, he took a swipe at old enemies, like Tom Kennedy of the Houston Post. One day I got a letter from Lalor with a check enclosed. The check was for $1,000, and the payee was left blank. In the past, Kennedy had claimed to have tapes catching Lalor in conflicting statements. Lalor’s letter said that if Kennedy would produce those tapes, I should feel free to make out the check to the charity of the reporter’s choice. When Kennedy told me that he no longer had the tapes but that he stood by his story, I suspected Lalor would take that as proof that he had been right again. Tearing up the check, I had the sense that he would go on, forever fighting, forever grinning, and never, ever understand.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Crime

- Houston