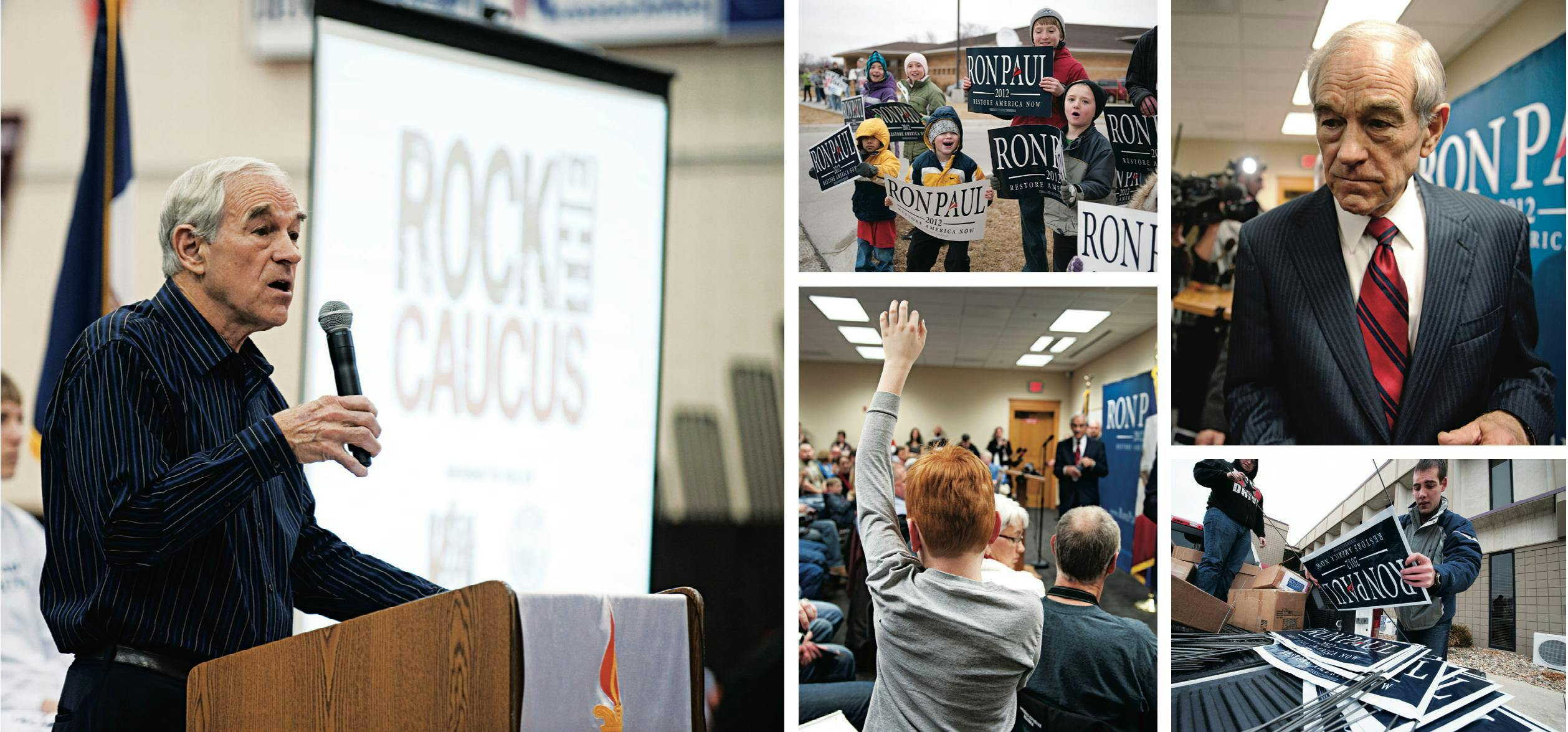

At 10:40 on the morning of the Iowa caucuses, Ron Paul entered the brightly lit gymnasium of Valley High School in West Des Moines surrounded by so many reporters thrusting so many recording devices into the airspace around his head that neither he nor his son Rand, the junior U.S. senator from Kentucky, could see the stage in the center of the gym’s sparkling parquet floor. As the cluster gradually advanced, amoeba-like, the director of MTV’s Rock the Vote, which was hosting the event, introduced Paul to an audience of perhaps five hundred juniors and seniors, which is to say all of Valley High’s new or soon-to-be-eligible voters. It was a good crowd. Michele Bachmann, who opened the morning’s program, had been greeted enthusiastically (“Who here wants to make a lot of money?” she shouted), while Mitt Romney’s four tall, handsome sons garnered polite attention. But when Paul finally reached the microphone, the applause was thunderous and sustained.

Paul, who is 76 and finally beginning to look a bit frail after some 35 years as a standard-bearer for the libertarian wing of the Republican party, quickly turned philosophical, musing about his recent surge in popularity with the millennial generation. “I don’t know the exact reason for it,” he told the students. “I defend the Constitution constantly in Washington, and that’s very appealing to young people. Sometimes the two parties mesh together, and it’s not too infrequent that I feel obligated to vote by myself. And when [young people] see that, they say, ‘He won’t go back and forth and will always stick to principle.’ ”

Paul has run for president twice before and has given a version of this same speech hundreds of times in his career, but he had never enjoyed a moment quite like this crisp January morning in West Des Moines. After decades spent in the political wilderness, he was polling dead even with fellow front-runners Romney and Rick Santorum in the first nominating contest of a wide-open Republican primary season. He was far ahead of his much-better-known fellow Texan, Rick Perry, despite the millions the governor had spent in Iowa, and was also sure to beat a resurgent Newt Gingrich. Even if he didn’t win the caucus outright, Paul had a top-three spot locked up, which meant that the media, never quite sure what to make of Paul, were finally treating him with respect. A growing chorus of pundits on the cable news channels praised his prolific grassroots fund-raising, his strong organization, and the loyalty and energy of his supporters, which he seems to have in abundance in every state.

What a difference a campaign cycle makes. In May 2007 I watched from an auditorium balcony as Paul was ritually sacrificed in front of five hundred of the Republican party faithful at a presidential primary debate in South Carolina. Then, as now, the GOP field was crowded with faces both familiar—like John McCain, Romney, and Rudy Giuliani—and less recognizable, among them the mild-mannered congressman from Lake Jackson, who was known outside his district in those days by only a scattering of libertarians around the country. Ignored by the Fox News moderators for much of the night, Paul thrust himself into the spotlight by suggesting, as the discussion turned to foreign affairs, that the 9/11 attacks had been a predictable response to our interventionist policy in the Middle East. Giuliani—still clinging to the “America’s Mayor” label almost six years after the tragedy that had made him a household name—ripped into Paul as the crowd roared its approval. Afterward, in the spin room, a throng of reporters offered Paul the opportunity to end his candidacy or apologize to the American people, neither of which he accepted. His evening was topped off by four minutes of live, on-air haranguing by Fox News’ Sean Hannity.

In those days, nobody wanted to hear what Paul had to say, not on foreign affairs and not on domestic policy either. Throughout the campaign, his screeds against the Federal Reserve System, his opposition to farm subsidies and corporate welfare, and his apocalyptic pronouncements about the coming bankruptcy of America fell mostly on deaf ears. He finished fifth in both Iowa and New Hampshire, and his campaign faded into irrelevance.

Four years later, Giuliani is rowing through the backwaters of the motivational speaking circuit, McCain is a grumbling presence in the Senate, and Paul stands at the fulcrum of a profoundly fractured Republican party. Having never truly ended his last campaign, and having clung tenaciously to the same contrarian ideas for decades, Paul has emerged as perhaps the most steadfast candidate in a field of constant flux. No moment was more emblematic of Paul’s new stature than the spectacle of the former pariah taking pity on Perry during the governor’s own debate nightmare, in November, when he inexplicably forgot the name of one of the three federal bureaucracies he had just promised to shutter if he reached the Oval Office. As Perry flailed and floundered, Paul, standing just to Perry’s left, gamely tried to fill the awkward silence. “It’s not three, it’s five,” he quipped, referring to his own plan to cut $1 trillion from the federal budget. Alas, there was no saving Perry, nor was there any escaping the takeaway from his disastrous evening: the ideas underlying his campaign would be much easier for him to remember if they were his own.

This is a problem that Ron Paul has never had to worry about. His political philosophy has not changed since his first term in Congress, in 1976. In fact, many of the ideas in Perry’s anti-government manifesto Fed Up!—such as the possibility of eliminating huge portions of the federal government—seem to have been cribbed from Paul’s voluminous writings. When Perry questions the constitutionality of Social Security and the federal income tax, he is channeling vintage Paul. That Perry would embrace such radical notions speaks volumes about how Paul has managed to climb up from the lower rungs of the conservative caste system over the past four years. There is no question that independent voters and more and more Republicans have moved closer to his position on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. A profound global recession, meanwhile, has put the nation’s precarious balance sheet at the top of the agenda, making Paul seem like a prophet to his longtime followers, and to those new to his message, someone worth at least a listen. Ron Paul’s moment, it seems, has finally arrived. The mountain has come to Mohammed.

Or so it seemed on the morning of the Iowa caucuses. Paul remains, and likely will remain, an outlier in the GOP field, but his idiosyncrasies have become strengths. A good part of his appeal is that he is so fundamentally unlike any of his fellow aspirants. This is why Paul’s negative ad castigating Gingrich as an unprincipled opportunist was so devastatingly effective and did so much to take the wind out of the onetime front-runner’s sails in Iowa. It had the obvious advantage of being true, but it would have rung hollow coming from a more polished figure like Romney, who can pander with the best of them. Likewise, there was something poetic about Paul’s dismissal of Donald Trump’s preposterous effort to host his own primary debate. “I don’t understand the marching to his office,” Paul told CNN. “I didn’t know that he had the ability to lay on hands.” Everyone knows that Trump is a pompous ass, but this sounds a lot better coming from somebody who looks like Jack Sprat, sounds like Jimmy Stewart, and publishes a combination cookbook and family album as campaign literature.

Truth be told, Paul is not a very good politician—not if your definition of political success includes realizing your public policy goals. Nothing about Paul suggests that he would, if he did somehow win the nomination, become another Ronald Reagan, the beneficiary of the last wave of right-wing populist anger that swept the country, in the late seventies. Paul doesn’t have the natural leadership skills to take the reins of government and steer the nation in a new direction. But his hard-core backers don’t want another Reagan, who, for all his talk about the perils of “big government,” oversaw enormous increases in deficit spending, mostly for the military, and added more layers of federal bureaucracy than he cut. Paul occupies that space where the libertarian right curves around and meets the anti-corporate, anti-authoritarian left. The “liberty” movement is a diffuse one, and Paul is not always careful about whom he associates with or what causes he lends his name to—a shortcoming that cost him votes when a batch of offensive quotes from his old newsletters, apparently ghost-written by someone else, resurfaced yet again during the stretch run in Iowa. But Paul’s apparent inclusiveness is also his strength. His people are just as likely to be found at tea party events as they are at Occupy Wall Street encampments, and their loyalty to his ideas may be Paul’s lasting contribution to the politics of the moment.

On the evening of the Iowa caucuses, Paul’s army of volunteers—recently arrived from all over the country—fanned out to caucus meetings across the state. At the Precinct 423 caucus, held at the First Church of Christ in the Des Moines suburb of Ankeny, not far from Paul’s Iowa campaign headquarters, about a dozen supporters arrived en masse just before seven o’clock. They were all neatly dressed and exceedingly polite and, with one exception, all young men. Perry had a champion too: his longtime friend and media consultant David Weeks was there with his wife. They were part of Perry’s “strike force,” a team of lobbyists, state officials, friends, and other volunteers dispatched to Iowa with some fanfare right after Christmas to boost the governor’s stagnant campaign. As the Precinct 423 voters made their way into the chapel, Weeks, dressed in a striking, floor-length black overcoat and cowboy boots, stood to one side of the church lobby, while Paul’s minions stacked themselves in quiet ranks in the opposite corner. Although they cannot cast a ballot, guests are welcome at caucus meetings and can even give nominating speeches on behalf of their candidates, if nobody from the precinct is willing.

After a member of the precinct gave an impassioned plea for Michele Bachmann, an invitation to speak on behalf of Jon Huntsman was met with silence and a snicker or two from the crowd of roughly 150 Iowans. Then it was Paul’s turn. Nobody from the precinct stood up; it seemed Paul’s local advocate had failed to show, or perhaps had gotten cold feet. A confused murmur moved through Paul’s volunteers, now clustered in the wide doorway at the rear of the chapel. Suddenly the young woman in their midst, who was maybe 23 and had long brown hair and comely features, strode to the front of the room. After a somewhat disjointed minute of extemporaneous remarks, she abruptly stopped and asked if anyone in the room had brought a copy of the letter that Paul’s campaign had provided for just this occasion. A teenager seated in the back row rose and shyly handed the young woman a copy of the letter, which she gratefully read before returning hastily to the safety of the lobby. As it happened, nobody stood up for Perry either, and Weeks was obliged to go to the front of the chapel and give his own nominating speech, which he dispatched with considerable aplomb.

Following the speeches, the votes were cast. I stood in the lobby and watched through a large serving window as precinct officials stood at the counter of a small adjoining kitchen and tabulated the names scrawled on little green scraps of paper. Weeks stood to my left, pen and paper in hand, while a young man from the Paul contingent (none of whom, under strict orders not to talk to the media, would even give me their name) looked on intently from my right. Weeks compared notes with both of us as he jotted down the bad news: Santorum and Romney were the big winners. Perry got just 16 votes and Paul 13. Gingrich got 23, which Weeks found hard to fathom. “That can’t be right. Gingrich can’t be doing that well here,” he said. Then he glanced at the crestfallen Paul maven beside me. “Oh well, as long as we beat you guys,” he said.

But when the final votes were tallied, it was Paul who had topped Perry, just as the polls had predicted, by a wide margin. At 21 percent, Paul wound up four points behind the leaders, Romney and Santorum, who finished in a virtual tie. The mood was victorious in the ballroom of the Courtyard by Marriott in Ankeny, where Paul’s supporters had gathered that evening to watch the returns. “It feels really cool to be a part of this,” said Carl Bisenius, a nineteen-year-old from Ankeny. When I asked what he liked about Paul, he singled out his anti-war stance, like almost every other young Paul supporter I spoke with that day. “When Obama was running, he said that he wanted to get out of Iraq,” he explained. What a lot of people didn’t realize, Bisenius said, is that Obama never intended to leave Afghanistan. “They are tired of being lied to.”

A week later, Paul finished a strong second in New Hampshire, more than tripling his 2008 vote total. This was less a threat to front-runner Romney, who finished fifteen points ahead of Paul, than it was a blow to everybody else in the race. Even after an amazing week, Paul remains a long shot to win the nomination. Nor is he seeking reelection to Congress, which means that this may be remembered as the pinnacle of his political career. Paul is unlikely to drop out, however, and he may yet play a role in the endgame, should the GOP wind up with a brokered convention. And there is always the possibility of a third-party candidacy, making his newfound momentum all the more alarming to GOP leaders. Whatever happens, this will likely be Paul’s last hurrah.

His long-term impact is harder to judge. Paul’s moment in the sun has coincided with a time of national crisis, and a crisis—so long as it lasts—is a great time to be a demagogue. Ron Paul is not that, exactly, but he is undeniably a fundamentalist: a man who sees every question in black and white, with little room for nuance and compromise. His bible is a doctrine laid down more than sixty years ago by an Austrian economist named Ludwig von Mises, who argued, in essence, that every government intervention in the market is bad and that more government inevitably means less freedom. This philosophy underlies every decision Paul makes. It is the source of his breathtaking adherence to principle, but it is also the reason his legacy as a lawmaker will be so limited. Policy-making is a messy process, especially in tumultuous times, and often requires even principled public officials to choose between two undesirable alternatives. Paul decided a long time ago that this was not his way.

But as a catalyst for change, Paul’s legacy may be more lasting. His willingness to gore the sacred cows of the Republican party, while managing to grow his base of support, has demonstrated that there is room for change in some of the party’s hidebound positions. And he also has lessons for Democrats, if they’re willing to listen, about the power of ideas and principles in organizing young people. Of course, Paul has another, much more tangible legacy, as a supporter I talked to on caucus day reminded me. Nick Sinclair, just sixteen, told me his biggest regret was that he’d never get a chance to vote for Ron Paul for president. But then he brightened. “Rand Paul,” he said. “Rand Paul will pick up where he left off.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ron Paul