It is a cliché around the Capitol that each legislative session has a personality unlike any other. Even clichés can be right on occasion, and this was one. The 69th Legislature was a surly child that had been dragged along to a place it did not want to go for the purpose of doing things it did not want to do, and by golly, somebody was going to have to pay for it. In the end it did what it was supposed to, but not before bruising a lot of feelings and a few fists as well.

Three things affected the collective temperament this session: money, Republicans, and the memory of last summer’s special session on education reform. The state’s tight fiscal situation contributed mightily to the grim looks on lawmakers’ faces. Most politicians don’t like to tell people no; this session they had little choice. The unpleasantness was exacerbated by the fear that Texas is nearing the end of the oil era and ought to do something to plan for the future. Empty treasury or no, the Senate wanted to invest millions in high-technology programs, mainly at UT and Texas A&M, while the House clung to a we-can’t –afford-it posture.

Which brings us to the rise of the Republicans, or to put it another way, the decline of the conservative Democrats. The realignment election of 1984 added 15 new Republican seats to the House, swelling GOP numbers in the lower chamber to 52—more than a third of the membership. Many of their gains came at the expense of conservative Democrats, and those who survived never forgot it for a moment. For the first time, conservative Democrats began to see themselves as dinosaurs, and they did not view their prospective extinction with equanimity. They made nervous jokes about how the new Republicans want government only to defend the shores and deliver the mail, but they didn’t joke at all about their own party, which was trying to foist on them a presidential primary bill that would have accentuated the Democrats’ liberal drift. Kent Hance’s switch to the GOP hit them hard; they sprouted buttons advertising, “We would rather fight than switch.” Meanwhile, the Republicans proved themselves shrewd and able politicians by not voting as a bloc but letting their numbers act as an incentive to cut spending and frivolity.

The hangover from the education reform session was the biggest factor of all. Last summer was the Legislature’s finest moment in years, maybe ever. Veteran members returned to Austin knowing that they had already done the most important thing they would do in their careers. What’s more, they had already dealt with the only issues ordinary Texans seem to care about: education, highways, taxes. The session began with no sense of urgency, no feeling that anything just had to be done, no reason except a budget to be there in the first place. It was anticlimactic from day one. Passions were spent not on issues but on personal hostilities; there were more fistfights and near fistfights than anyone could remember, and one legislator even treed a student during an outdoor protest of tuition increases.

Despite the gloomy atmosphere, the Legislature came up with a session to be proud of. For that we can thank the much-maligned Texas constitution and its equally maligned injunction that the Legislature meet every two years for no more than 140 days. All the ingredients were present for a stalemate: torpor, factionalism, the absence of pressing issues. Had the Legislature been a year-round body like Congress, we still wouldn’t have a water plan or a budget or a hazardous-waste law or dozens of other good bills that are headed for the law books. The deadline provided the urgency that nature had omitted, and the Legislature lurched toward its destiny almost in spite of itself.

Under the pressure of time, the philosophical and party rifts became an asset. Compromise was the only way to beat the clock. Consequently, although this was the most conservative Legislature in recent times, its product was also one of the most balanced in recent times. There seemed to be something in everybody’s stocking: indigent health care (passed during a brief special session after it became the one thing that time really did run out on) and a hunger package, tough new crime laws, the first glimmerings of environmental concerns in a water plan, a leaner bureaucracy, decent if not lavish funding for universities, even a consumer bill or two.

That augurs well for Governor Mark White, who faces reelection in 1986. Never mind that White had little to do with the session’s success. He has never bridged the gap between electoral and legislative politics; he paints with too broad a brush, full of generalities when dealing in an arena where all the battles are over specifics. On subject after subject, on fee increases, blue laws, funding for indigent health care, a telephone tax adjustment, White’s waffling led to controversies that could have been avoided. Did he want a cigarette tax to pay for indigent health care or didn’t he, and why wouldn’t he make up his mind? (When he finally did decide-nix on the tax- it was the Friday before the session ended). But if he isn’t very good, he at least is lucky. Mainly, he’s lucky that the House and Senate are in good hands and can insulate him from having to lead.

Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby is the best thing that has happened to Texas government since the oil severance tax. He has the best vision of what Texas should be, the best understanding of public policy, the best sense of how politicians should comport themselves, the best ideas, the best staff. He has defined the modern Senate. Speaker Gib Lewis, in his second session—five fewer than Hobby—showed some surprising signs of moving in the same direction. He too is molding his members into the kind of legislators he wants them to be: those who do their work in the coolness of committee deliberations rather than the heat of floor debate. That makes for less excitement but better legislation. He is a member’s Speaker who uses his power to keep the train on the track rather than to run over people. His main weakness is his indifference to the details of issues, which sometimes leaves him blind to impending trouble (such as the predictable deadlock that occurred in the water conference committee), and his how-ya-doin good-ol’-boy tendencies, which make him at times an easy caricature. (He asked a visiting group of paraplegics to “stand up and be recognized,” for instance, and proclaimed at a women’s lobby luncheon that “I’m so happy to be here. I love girls.”) But no one can question his good intentions or his courage. He stuck by education reform despite attacks from all sides, and during the special session, in the middle of the most partisan fight since Reconstruction, he broke a tie to save indigent health care.

Our criteria for the Best and Worst lists, as always, rest on personality rather than ideology, because that is how legislators judge their colleagues. Nor did we base our selections on issues, although with money as such a major factor in the session, it was inevitable that work on the budget, good or bad, became a short route to one list or the other. The constants of politics are intelligence, integrity, open-mindedness, fairness, and the desire to find a way to advance the ball. The common characteristic of bad legislators is their absence of a constructive purpose. We judged harshly those who elevated partisanship and emotional issues above the business of the state. There just isn’t time for that sort of thing in 140 days.

The Ten Best

Paul Colbert

35, Democrat, Houston

If brains alone got you on the Best list, this would be Colbert’s third straight appearance. But in sessions past, his cerebral, compulsively talky style—as foreign to the gregarious, backslapping House as Margaret Mead must have seemed to the Samoans—raised the hackles of other members and limited his effectiveness. He diluted his stock through sheer overexposure at the microphone, explaining endless amendments in excruciating detail and playing the kamikaze. Then something called HB 72 changed Colbert’s life: during last summer’s special session on that educational reform bill, brains were in. His awesome knowledge of school finance proved essential. He was ubiquitous (colleagues fretting over the bill in the men’s room were startled when Colbert materialized from a stall to set them straight); people who had tuned him out suddenly tuned him back in. By the end, he had forged ties with the leadership, changed his image (a near-impossible feat in the unforgiving House), and discovered that he was on the inside. What’s more, he discovered he liked being on the inside.

For one thing, there were rewards—his spot this session on the key Appropriations Committee, for example. Again he was everywhere, speaking for this program and against that program, busier than a squad of trauma-room doctors on a full-moon Saturday night. Kept HB 72 reforms patched together in the face of attacks from House honchos; spared parks from a devastating raid; single-handedly resuscitated a scholarship fund for bright students who want to be teachers. Ferreted out loose money in unlikely places (“Colbert could find money inside this plant,” asserted one member, fondling a fern); used his fertile mind to figure out how to divert $15 million in interest from the usually sacred highway fund when others were insisting there were legal impediments. Tried to make the point that there’s fat in the higher education budget by moving to phase out UT-Permian Basin—and, much to his own surprise, got the votes; repeated the performance on A&M-Galveston. Because those were the most publicized cuts of the session (they were later restored), some accused Colbert of grandstanding, but that’s the price you pay for winning. At least no one accused him of not making his point.

Dogged as a terrier, when Colbert couldn’t get what he wanted from the House, he went after it in the Senate. After the House axed funding for the Texas Research Institute of Mental Sciences (TRIMS), Colbert nosed around until he found an obscure Senate bill that could provide funds to transfer TRIMS to the UT system. Then he tracked Appropriations conferees to a back room and waited till 12:30 a.m. to snatch Chairman Jim Rudd as he exited and to make his pitch. He won, saving four thousand desperately needed mental health beds for Houston. “Colbert is the most tenacious sumbitch in the world,” testified a battle-worn lobbyist. “When he gets hold of your pants leg, say goodbye to your trousers.”

The contrast between the new Colbert and the old was starkest during the billboard debate. Last session had members gnashing their teeth and voting him down by a landslide as he ran with fifteen different amendments. This year saved his ammunition for one logical, eloquent attack on the bill, arguing in a vernacular that would have come hard to the Colbert of yore. “That ain’t right! This is!” he finished succinctly. He lost, but he lost like an insider, and in a legislative career that can make all the difference.

Chet Edwards

33, Democrat, Duncanville

We have seen the future and its name is Chet Edwards, your senator for the eighties. Young (at 33, the youngest of his peers). Handsome, straight-arrow bachelor (women swoon, strong men mutter enviously). Aggie with an M.B.A from Harvard who manages to please both consumers and corporate types. Cast in that all-important Hobby senatorial mold: courteous, conscientious and gentlemanly. Sponsor of a legislative program as clean and glamorous as he is. In short, an impossibly burnished package with a surprise inside—real substance.

It’s tempting to trivialize Edwards on the grounds of that dazzling physical presence. Sure, the camera loves him and he loves the camera. Yes, he exudes the grave, Goody Two-shoes formality of a pretty face afraid of not being taken seriously. Yet if his performance proves anything, it’s that one takes Edwards lightly at one’s own risk. Spent the session cannily carving out a niche for himself, a precocious step that set him apart from the pack of sophomores. His turf, high tech, plugged right into the timely, post-oil-boom theme of economic diversity. Chaired an interim high-tech commission, then passed a panoply of bills welcomed by the computer industry.

Displayed a high techie’s love of data; craved information and knew how to use it. Good ol’ boy arguments to keep blue laws intact left him cold; he demanded documentation of how employees would be hurt, and when it wasn’t forthcoming, voted for repeal. Took on the phone companies single-handedly by trying to put a two-year ban on local measured service (LMS), a plan that would charge customers by number of calls, time, and duration. Armed with multiple version of the LMS bill and amendments for every objection, he organized one of the most impressive committee hearings in recent memory. Then, to everyone’s surprise, miraculously pried his bill out of committee after the phone folks had boasted that it was dead. Whoops—time to reprogram the computers; Edwards was somebody to contend with.

Worked yeomanlike on a range of issues that were anything but easy sells. Cleaned up and passed a Senate bill to continue the controversial Health Facilities Commission. Passed his painstaking redo of the election code (a feat that had eluded others for the past three sessions), and even prodded a presidential primary bill through the Senate. Championed nursing home reforms against wily Senate vets, one of the few moments when his smooth countenance could be seen to waver. Put it down to a naiveté that’s both a blessing (doesn’t lie, doesn’t understand what’s impossible) and a curse (doesn’t catch the sneaky stuff).

His batting average? Oh, that. Saw some major bills (LMS, primary, health facilities) go down to defeat in the House, but because all ran into booby traps, he emerged from his battles almost without blemish. Even hardened lobby cynics had to take notice. Marveled one, “You keep looking for the warts, but there aren’t any.”

Charles Evans

46, Conservative Democrat, Hurst

The perfect Puck, a redheaded imp who exults in making mischief almost as much as he exults in making policy. Not the sort of legislator you’d want a high school civics class to follow around, but when all was said and done, Evans had contributed more to the public interest than just about anyone, even allowing for a deduction or two along the way.

Carried a satchelful of good bills: a state Grace Commission to root out inefficiency and waste, a requirement that insurance companies pay for alcoholism treatment, a ban on local measured phone service—and passed all but the telephone bill. Constantly rescued the alcoholism bill from the insurance lobby’s noose, once when Speaker Lewis was about to spring the trapdoor. Just when he was getting fitted for a halo, showed up with a bad ol’ bill that tried to close some open records, which figures; Evans himself is about as open as the Berlin Wall.

Proved it in spades as czar of the Sunset process, in which a host of state agencies had to be reestablished by the Legislature or cease to exist. As chairman of the House committee overseeing Sunset, Evans delayed action on bill after bill until the fading hours of the session. Bureaucrats were putting out résumés. The Senate was having fits. House sponsors were wringing their hands. Lobbyists were going nuts. And Evans? He was loving it. Nothing is more obnoxious to Charlie Evans than a dead calm.

Then Evans opened the floodgates, and the House was awash in three-hundred-page Sunset bills whose contents he alone knew. If you are asking yourself whether that bears any resemblance to good government, you are only echoing what just about everybody in the Capitol was saying. But there was method in Evans’ madness. No lobby in the Capitol can match the power of the entrenched bureaucracy and its clients, all of whom wanted Sunset to be a rubber stamp for the status quo. Oilman Ed Cox, chairman of Parks and Wildlife, didn’t want Evans messing with his agency. H. Ross Perot didn’t want drug treatment touched. The hospitals wanted the Health Department left alone. The river authorities wanted Evans to keep his hands off the water agencies.

By waiting until the last minute, Evans diluted their power and created a fair fight. He gave Sunset a chance to do what it was meant to do. When it was all over, he had modernized drug treatment, arranged for the sale of some obsolete state hospitals, turned the sluggish water bureaucracy inside out, and in general left his stamp on state government for the better—even if he did slip in funding for a new state park in Fort Worth. Best of all, he had a whole lot of fun.

Ray Farabee

52, conservative Democrat, Wichita Falls

What else is left to be said about this good, gentle man? That he has more virtues than Mother Teresa? No, we listed a lot of them—conscientious, hardworking, smart, fair, independent, an air of inner strength—back in 1977, the first time he appeared on the Ten Best list. That he operates on a different level from anyone else, not as the voice of a single district but as the trustee of an entire state? Nope. Said it in ’81. That he is the most respected member of the Legislature, who defines by example what a senator should be? Sorry. That was ’83. So leave it at this: Ray Farabee is the sort of person who could give politics a good name.

Everybody wanted Farabee to carry their bills, though his floor skills are just ordinary, because, in the words of a Senate staffer, “having him as your sponsor is like the Good Housekeeping seal of approval.” His legislative program would have sunk a supertanker: judicial reform, blue law repeal, toxic waste regulation, computer crime control, protection for time-share purchasers, securities deregulation, a bond procedures act, fine tuning of parole procedures, indigent health care. Passed most of it despite refusing, as usual, to use his chairmanship of the busy State Affairs Committee as a lever to shift votes, as other chairmen have done since time immemorial.

Remarkable above all for his fairness. Never has a hidden agenda, never gets petty, never tries to get even, never overlooks the weak and helpless. As a member of the Senate’s budget-writing team, looked out for agencies aiding delinquent youth, abused children, and the mentally ill. Has a deep-rooted faith in the process of compromise; seemed genuinely offended by the give-no-inch attitude of House budget negotiators, lecturing them that “the act of compromise is not just coming up here to sign off on the House bill,” and helped fashion the final agreement.

His one shortcoming, if it is that: he’s too trusting in the process, too aloof from winning or losing. But he’s doing better. When he was informed that three of his judicial reform bills had died in the House after he had worked on them for a year and a half, Farabee actually threw down his ballpoint pen. On the session’s closing night, he even risked exposure to the teeming House floor to inquire after the fate of indigent health care. “They’re killing our bill,” someone shouted to him amid the pandemonium. But there was nothing he could do. He was out of his element, a Lord among the Commons.

Bob McFarland

44, Republican, Arlington

The Legislature’s answer to Red Adair. Are fires raging over billboard regulation? Is a precarious agreement on tuition threatening to blow? Just call on McFarland, who institutionalized his role as troubleshooter-in-residence this session. Cleared the decks of his own program early (including an important bill to extend insurance coverage to alcoholism treatment), which freed him to prowl the halls writing amendments and sealing compromises—a roving subcommittee of one. Everyone from Bill Hobby and Gib Lewis to worried senators and reps sought out his help, but his fix-it missions seemed not so much assignments as enactments of a primal urge. Born to write off-the-cuff amendments that clean up problem bills, he composed them on the floor, on the run, on napkins at the Austin Country Club. Granted free passage by his colleagues, who know that he’s not straightjacketed by partisan politics and that his only motive is to make the process work.

McFarland has more fun ferreting out negotiable areas than most people have dancing the cotton-eyed Joe. His technique: coax the warring parties onto the dance floor, perhaps bringing in a heavy like Hobby to make a “strong suggestion.” Sit down with one side and throw out hypothetical questions—“What if we did this?” Go to the other side and ask, “What if we did that?” Finally, proclaim, “This is the way it’s going to be.” It worked on the nightmarish billboards dispute, when McFarland ended two years of warfare by crafting a compromise that both the industry and the cities that wanted regulation could accept. It worked during the wiretapping filibuster, when he fashioned an agreement that persuaded Craig Washington to sit down. When wrangles over tuition threatened to poison the entire session, McFarland raced between House liberals and Senate conservatives with a cut-and-pasted amendment; soon there was a deal. Such exploits explain why he is crucial to Hobby’s vision of the Senate as a businesslike, non-confrontational body: without McFarland, the blood would flow.

By session’s end, he was fixing bills that nobody particularly wanted him to fix. Kept trying to pump life into the hock-your-home (a.k.a. second mortgages) bill long after everyone else had pulled the plug. Refused to let the bill banning open containers in cars die a decent death; wrote language that won the extra vote to bring it out of committee. If he has a blind spot, it’s that he has trouble accepting that some bills are born to die.

Withstood the legislative heat with his trademark cool aplomb; eternally precise in his language, his grooming, his carriage, his neat-as-a-pin desk. One evening, after what senators euphemistically call a l-o-o-o-n-g dinner, McFarland put his hand out to hold an elevator while he talked to two reporters. It got stuck between the doors. The reporters panicked. “It’s not my hand I’m worried about,” McFarland assured them, unflappable to the last. “It’s my cigarette.”

Bill Messer

34, conservative Democrat, Belton

The dominant figure in the House in every way—carrying bills, devising strategy, working the floor, setting the agenda, and, ever and always, generating controversy.

As elusive to define as the elephant to the blind men of Indostan. Some regarded him as a card-carrying extension of the business lobby, citing his sponsorship of special-interest bills (restricting local ordinances against billboards, requiring the wearing of automobile seat belts), but guess who passed more labor bills than all but one other member during the session? Some criticized him for never doing anything for people who can’t take care of themselves, but guess who passed a bill protecting families of organ donors and helped save indigent health care with his floor leadership during the special session? Some say he loved playing the game more than getting public policy into law, but guess who helped devise the plan for restructuring the state water agencies and fought to tie the number of state employees to population? One colleague said it best: “He’s so good he’s bad; he’s so bad he’s good.”

Nothing he did provoked so much contention as his chairmanship of the pivotal Calendars Committee. Functioned as Saint Peter, a description made more apt by his cherubic cheeks, as he guarded the Pearly Gates through which all bills had to pass to reach the House floor. But was he saint or sinner? Some, especially senators who saw time run out while their bills languished in Calendars, accused him of abusing his power. They were wrong. Messer did not use a fraction of the clout his position gave him. He didn’t kill important bills he opposed (blue law repeal being one), nor did he hold bills hostage in exchange for help for his own program. Instead he ran Calendars like the eighteenth-century conservative he is—someone who believes that process is just as important as substance. He choreographed the entire session to keep the House from falling into the partisan and ideological traps that lurked everywhere, and he succeeded.

The one thing no one questioned about Messer was his skill. Enormously knowledgeable, both about legislation and about the world beyond (in casual conversation he has been known to launch into disquisitions on subjects ranging from electrical cogeneration to the shifting politics of Belize). Quick on his feet; countered the toughest arguments in debate; possessed an uncanny ability to assess any situation. During the conference committee on educational reform last summer, onlookers were surprised to see Messer leave his seat on the House panel and take up residence on a sofa next to Bill Hobby’s staffers. He had correctly deduced that they, not the senators, were the people he had to persuade. As usual, he did.

Hugh Parmer

45, Democrat, Fort Worth

Committed more good deeds than a troop of Boy Scouts. Found money for the hungry, rescued women and animals in peril, slipped neatly into the consumerist, do-gooder shoes vacated by Lloyd Doggett—and unlike Doggett, did it all without turning off his peers. What’s more, he did it without Bill Hobby’s benediction, which made Parmer one of the few members of either house to forge a record of accomplishment independent of the presiding officer.

Carved out the hunger issue as his own: headed a year-long interim study, put together an $18.5 million bill to help feed needy children, pregnant women, the elderly, and the unemployed, then spent half his legislative time guiding the bill over a hundred hurdles. Got conservative senators on his team with an astute appeal to the session’s great theme—cost-effectiveness—arguing that good nutrition would save taxpayers health costs in the end. Worked the House harder than any senator in years, marshaling a multilobby force and deploying it by means of a chart spread across his whole office wall, as intricate as a plan for the invasion of Normandy. Won $15 million in funding, a crowning victory in a lean year.

Meanwhile, the ever-cheerful Yalie foiled the mugging of a female Capitol employee by dropping his gym bag, shedding his glasses, and pursuing her assailant. Failed to pass dog kennel regulation or prohibit use of live animals as dog-racing lures but did rescue a turtle trying to cross Twelfth Street against heavy traffic. Even came to the aid of Chet Brooks, offering him a way to avoid the indignity of defeat by his own committee; foolishly, Brooks declined.

Sainthood? Not quite. Detractors grumbled that Parmer dragged out hearings with unnecessary chatter. Temporarily blew his good-guy status during a filibuster by ribbing Senator Carl Parker about his indictment, a terrible gaffe that flouted unwritten rules of Senate courtesy and almost led to fisticuffs. But Parmer was so contrite that even Parker found it hard to stay mad at him.

Reclaimed any lost stature by pulling off one of the session’s most masterful plays in the panicky final hours. Had squeaked a badly needed consumer bill—extending group insurance policies for spouses after death or divorce—past a hostile industry, only to find it trapped behind a legislative logjam in the House. What to do? Attach it as an amendment to an innocuous insurance measure already past the logjam. How to get the votes? Get the attention of the logjam’s architect, Bill Messer, the House’s most powerful member. Knowing Messer’s beloved billboard bill had yet to pass the Senate, Parmer donned a button reading, “No Bills, No Billboards,” brandished his running shoes, and threatened a lethal filibuster against Messer’s bill. Instantly, Messer summoned a swarm of billboard lobbyists to descend upon the House, treating amused neutrals to the rare spectacle of business lobbyists pleading for Parmer’s consumer bill. When both bills passed, Parmer had proved that nice guys really can finish first.

Jim Rudd

42, conservative Democrat, Brownfield

Not since Peter Graves has anyone undertaken such a mission impossible: come up with a state budget acceptable to both the parsimonious, Republican-heavy House and the free-spending, Democrat-dominated Senate. Somehow, the rookie chairman of the House Appropriations Committee beat the odds.

Tall, gray, and distinguished; could be typecast as a cattle-town banker in a movie about the open range era. Played the role to the hilt, doling out money with firmness and fairness but never favoritism. Thanks to Rudd, in a year when there was less money to go around than anyone could remember, there was also less rancor about the appropriations bill than anyone could remember.

Produced the state’s first kosher budget—no pork. Led by example, resisting special treatment even for Texas Tech, the item nearest and dearest to his heart. By the time the committee bill reached the House floor, Rudd’s restraint had already elevated him to demigod status among his colleagues. When the conservative caucus, led by Tom Waldrop of Corsicana, tried to cut the bill by 2 per cent across the board, Rudd argued, “If you vote with Mr. Waldrop, you are saying that all the hours that the Appropriations Committee has put in are out the window.” By a 90-50 vote the House sided with Rudd. After the debate Rudd received the rarest of House tributes, a standing ovation.

But the battle was only half won. Still ahead lay the conference committee showdown with the Senate. The central issue: Rudd’s insistence that state employees receive a pay raise in order to forestall unionization. When the Senate resisted, the five House conferees showed up wearing blue-and-white buttons saying, “Rudd’s Right.” Soon the buttons were everywhere, on House members, on staffers, on lobbyists, even on reporters—on everyone, in fact, but grumpy old senators, who had rival buttons made up praising their chairman. Rudd was right, and in the end he prevailed.

Mike Toomey

35, Republican, Houston

Mike the Knife. The supreme cutter; a Texas version of David Stockman, who knew where the budget bodies were buried and was intent on exhuming and dissecting every last one.

Though a newcomer to budget writing, had all the qualities essential to mastering this most difficult of legislative arts: industry (toiled late at night, on weekends, and before breakfast), inspiration (hit upon the idea of holding Sunday conferences with individual budget staff experts, extracting information in private that could never be gleaned in public), a mind for detail (“He knows where every office is, what it looks like, who works there, and what they do all day,” marveled one senator after a head-to-head bout with Toomey), and objectivity (a staunch partisan Republican, but never let partisanship guide his stiletto). Said one thirty-year Capitol veteran, “There’s never been anyone who knew the budget like Toomey.”

Bureaucrats feared him. Democrats respected him. But Republicans deferred to him. When they wanted to know how to distinguish cost-covering fee increases from taxes, Toomey came up with a go-no-higher number that GOP leaders called the Toomey line. It virtually became a Republican battle cry: “That good old Toomey line/That good old Toomey line/We’ll never spend a penny more/Till Toomey says it’s fine.”

The pivotal figure on the ten-member House-Senate conference committee that wrote the final budget. Sat by himself on a separate tier, surrounded by mountains of file folders containing notes about every state agency, so that he could readily gain the ear of Chairman Rudd. Without grandstanding, quietly forced cut after cut upon reluctant senators, whose knowledge of the bill was no match for his. Even managed to eliminate $4.4 million from attorney general Jim Mattox’s budget—no easy feat, considering that two of the senators on the committee would like Mattox’s job (and budget) for themselves.

The sight of Toomey at work was one of the lasting images from the session. Walking around with his arms folded, a very private man, protecting himself and his space; or seated, dark and intense, with a piercing, quizzical gaze that looked through the eyes of an adversary as if to probe his brain. He was unforgettable, essential, a person without whose contributions there would never have been money to balance the budget. But for all his brilliance, Toomey held fast to a narrow ideology that had room for no-new-taxes, law-and-order, and little else. The question now is whether he will grow beyond technical artistry into the kind of statesmanlike leader that Republicans in the House so desperately need before, as will inevitably occur, their party ascends to power.

Tom Uher

47, conservative Democrat, Bay City

As refreshing as an eddy in a stagnant pool; the most independent member in a House so docile toward the leadership that it seemed as if opposition had been prohibited in the rules. Embodied the best qualities of the old-line legislator: hewed to a consistent philosophy, yielded to reason but not to pressure, reveled in a floor fight, didn’t care a fig about offending the leadership, and didn’t live in constant dread that someone back home was peering over his shoulder on every vote.

All of which made him Mr. Right for one of the toughest jobs: overseeing the House budget for higher education, the most sensitive part of the appropriations bill. Faced intense pressure to give special treatment to UT, A&M, all the private colleges, and Baylor medical school, and stood up to them all.

Laid aside his deceptively clownish streak (on the floor he dispensed backslaps, bear hugs, and one-liners like a Shriner at a national convention) and applied his deep-felt agrarian conservatism to the sober nitty-gritty of appropriations. His thankless assignment: to divide up a diminished pie and still satisfy the state’s most voracious appetites. Uher’s recipe:

– Concentrate on the basics. His budget pumped $250 million more into faculty salaries than earlier budget staff recommendations, $60 million more into departmental operating expenses, $30 million more into libraries.

– Ignore the frills. Every school clamored for extra bucks to fund special items that had little to do with basic education—robotics programs, schools of industrial relations, and the like—but were great for grant chasing. In a lean year, Uher decided, they would have to wait.

– Woe to the boondoggles. Uher proposed deep cuts in dubious doles to private colleges and lushly funded Baylor medical school. Why subsidize them, he asked reasonably enough, when there’s no money for our own schools?

– Protect the weak and let the strong fend for themselves. Uher stuck up for junior colleges, the traditional route off the farm for rural Texas. They received $96 million more than the budget staff recommended. But the UT and A&M system offices, which have access to all that oil money, got not a penny more.

What did Uher get for his troubles? Martyrdom. He was shut out of a well-deserved slot on the budget conference committee; by then he had stepped on too many sensitive toes (including Speaker Lewis’, who hadn’t forgotten that Uher had once eyed the speakership himself). Without Uher, the big powers had a field day in the conference committee, especially UT and A&M in the area of special items for high tech, while junior colleges suffered mightily.

But Uher refused to lie down and play dead, even after he was dumped. Hours after learning of his omission, he was leading a floor fight against higher college tuition proposals, forcing the Speaker to cast a rare vote to guide his straying flock. And Uher may not be through yet. With a major study of higher education scheduled for the next two years, you can bet that he’ll be fighting those battles all over again.

The Ten Worst

Chet Brooks

49, Democrat, Pasadena

A prosecutor’s job is not always a happy one, particularly when the accused is dean of the Senate, a man who has compiled a long history of accomplishment in the social services. But this session the spotlight shone on health issues, and in its glare Brooks showed himself to be not a leader but a mean, petty person bent on undoing his own good works. Before convicting him of conduct unbecoming a dean, let us give sober attention to the indictment.

Count one: Got too close to the lobby. Brooks styles himself the father of nursing home reform, but over the years has grown tight with the industry, a big-bucks contributor to campaigns. So instead of carrying the ball on a Sunset bill loaded with much-needed nursing home reforms, Brooks turned himself into the industry’s premier apologist. Those nursing home abuses you’ve been hearing about? State inspectors were the problem, not the nursing home, Brooks told senators. Then he fought successfully to reduce penalties and fines for those abuses and to kill a fund that would have paid off damage suits against offending homes.

Count two: Tried to sabotage key indigent health care measures. Did he step to the fore on the important indigent health care package? Nope, just the opposite. He did his damnedest to save hospitals from beefing up their charity-reporting procedures and to spare them from civil liability and license loss if they kicked out critically ill patients. Even Brooks’ own committee rebelled by voting against him unanimously—a stinging chastisement for a Senate chairman to endure. Brooks left in a snit, peevishly blamed House indigent health care sponsor Jesse Oliver for his setback, and then at a local watering hole, did the unheard of, telling Oliver never to lobby Brooks’ committee again.

Count three: Kept dropping the ball on the powerful Finance Committee. Committed himself to help fund a program to prevent child abuse; on the critical day, he was missing in action. As the session wore on, Brooks’ attention wore short. His work on Finance slipped far below his usual standard—so far that Hobby took the unprecedented step of not reappointing Brooks to his prized seat on the conference committee that negotiated the final state budget. Brooks had already tested Hobby’s patience by opposing revenue-raising measures no conferee was supposed to oppose; it is a Senate axiom that if you don’t vote to raise the money you don’t get to spend it.

Count four: Set an abysmal senatorial example. Among his undeanly deeds: made a brutal personal attack on the commissioner of higher education in floor debate; questioned a fellow senator’s integrity during the filibuster of a shrimping bill; seriously breached Senate etiquette by launching a filibuster without first informing Hobby or the sponsor; blustered unbecomingly whenever a bill strengthening campaign reporting laws reared its head.

Appeared more interested in dining out on the lobby than in doing his work. “Sometimes a person can stay too long,” said a former-Senate-aid-turned-lobbyist. We agree, and find the defendant guilty as charged. But in consideration of his past record, we are prepared to let him out on shock probation, provided that he heeds this quatrain, originally written for the queen consort to George IV: “Most gracious Chet, we thee implore/To go away and sin no more,/But if that effort be too great/To go away at any rate.”

Bill Ceverha

48, Republican, Richardson

An absolute zealot who, but for an accident of birth, could have been a Bolshevik revolutionary or a Middle Eastern bomb thrower. Shares the same drive to lay waste to anything that stands in opposition to his extreme conservative ideology, even if the innocent have to suffer in the explosion.

A case in point: The Texas Commission for the Deaf. Its newsletter listed the subjects to be covered by 22 panels at a deaf women’s conference in California. Uh-oh. One was called “Gay Deaf Women.” Here came Ceverha, with handouts and speeches condemning the agency.

An ex-TV anchorman whose understanding of the subtleties of politics runs about ninety seconds deep. Watched fellow Republican Mike Toomey put on a clinic in the Appropriations Committee about how to cut attorney general Jim Mattox’s budget—stick to logic, avoid partisan issues, don’t get the Democrats riled up—but absorbed nothing; undermined Toomey’s patient efforts by trying to riddle Mattox’s consumer and environmental division.

Ceverha did chalk up one victory: he forced the resignation of an old foe, Sarah Weddington (a leading proponent of free choice regarding abortions), by revealing that she had taken excessive time off from the governor’s Washington office to travel at state expense. But Ceverha couldn’t find the brakes. Not content with getting Weddington, he tried to cripple the division where she had worked by cutting its funding 70 per cent. He got 2 votes out of 29.

It was vintage Ceverha: unable to stick to merit, driven by compulsion not just to beat his opponents but to discredit everything they are associated with, possessed of a deep incivility. He does not fit into a place where the formalities—“I reluctantly rise,” “Does the gentleman yield?” “Asks unanimous consent”—serve as constant reminders that things are never supposed to get too personal.

During the session’s last weekend, Ceverha couldn’t find the brakes once again. Supporters of a bill extending the life of a controversial state agency wanted to add an antiabortion amendment to attract conservative votes, but Ceverha, who had been trying to pass an antiabortion law for years, would not hear of it. “I consider this to be a slap in the face to me and every other person who has been active in the right-to-life movement,” said Ceverha, exhibiting a pre-Copernican predudice that everything must rotate around him. He proceeded to attack the amendment’s author, a mild, highly regarded South Texan named Ernestine Glossbrenner, for insincerity and insufficient right-to-life credentials.

By the last night of the session, nobody wanted to hear from Ceverha anymore. But they had to. At three minutes to midnight, the indigent health care bill came up for debate. Ceverha took the microphone to talk it to death. Boos and hisses filled the chamber from all sides. At midnight it was over. But it wasn’t. The next morning everyone was back for a special session, courtesy of Bill Ceverha.

Jerry Clark

41, Conservative Democrat, Buna

A dull razor who had the misfortune to be called into service from the forgotten shelf where he had rusted away during previous sessions. The predictable result: knicks, scrapes, and scars everywhere.

Couldn’t cut it as chairman of the House Retirement and Aging Committee, a dumping ground reserved for members out of favor with the Speaker. Inflicted further punishment on hapless members by playing Jekyll and Hyde—courteous and patient on retirement matters but vicious and brutal on aging. Any bills hinting at nursing home reform were DOA; until pressured by Speaker Lewis, Clark refused to let them out of committee. Then, when one somehow escaped his clutches only to be defeated on the floor, Clark celebrated its demise by exchanging high-fives, smirks, and chortles with fellow good ol’boys at the back of the House chamber. Observed a fellow chairman, “He just turned his committee over to [nursing home lobbyist] Pat Cain.”

Out of his depth on the House-Senate conference committee that feuded over the state water package until Lewis threatened it with termination. The only East Texas representative among the House contingent, but you’d never have guessed it. Joined other House panelists in ignoring senators championing East Texas issues like sewage treatment bonds, flood control, and protection of bays and estuaries.

As unresponsive to stroking as a petulant house cat. Sought out by legislative budget staffers to sponsor a crucial retirement bill that would raise almost $30 million for the state; typically, never got around to it, requiring much overworked Appropriations chairman Jim Rudd to resuscitate the bill.

Through those three stories—indeed, through his entire career—runs a common thread. Jerry Clark is not so much evil as he is a throwback to the old-fashioned, pre-Sharpstown scandal kind of legislator who avoids the serious work of legislating at all cost. It is simpler to kill a nursing home bill than to fix it; it is simpler to glower and snipe at senators than to negotiate a water compromise; it is simpler to let someone else carry a bill than to pass it yourself. He does not want to advance the ball; he doesn’t even know how. All he knows is how to get in the way.

Gerald Geistweidt

37, Republican, Mason

The greatest champion of the negative since Kodak. Acts as if “yes” is a four-letter word, change is good only for vending machines, and compromise is a communicable disease.

The personification of intransigence on the conference committee appointed to negotiate a state water plan. The appointment was unfortunate for Geistweidt, since negotiating involves two things—give and take—and he believes in only one of them. It was also unfortunate for the state, since Geistweidt suffered from political nearsightedness: he couldn’t see past the boundaries of his district. Predictably, showed antagonism toward anything that benefited any part of the state except his own, especially the Senate’s number one priority, guaranteeing fresh water for bays and estuaries. “Why should we release perfectly good water just to protect the crisscross snail darter?” he harrumphed. Then he tried to make senators choose between using water for bays or for Houston, Corpus Christi, and San Antonio, prompting a senator to ask, “Do you represent Houston?” Geistweidt: “No.” Senator: “Do you represent Corpus Christi?” Geistweidt: “No.” Senator: “Do you represent San Antonio?” Again Geistweidt got to use his favorite word. Senator: “Then you’re meddling, Mr. Geistweidt.” Whereupon the senators broke off negotiations. Only after Speaker Lewis threatened to replace Geistweidt and company did the conferees reach an agreement.

Nothing seemed to upset him so much as the prospect of harmony where there might be discord. Business and labor could agree on an unemployment compensation compromise—but not Geistweidt. No sooner had a compromise budget for the Agriculture Department been presented to the Appropriations Committee than Geistweidt made a motion to torch it. When fellow Republican Mike Toomey tried to make cuts in Jim Mattox’s budget more palatable to the committee’s Democratic majority, along came Geistweidt with a motion to make them more punitive. Looks the part of the heavy; scowls, registers disgust, folds his arms, rolls his eyes heavenward, betrays no hint of the person who, away from the heat of the battle, has been known by his colleagues to pick a mean guitar and carry a nice tune.

His closed mind renders his skills useless. On the last weekend, Geistweidt led a floor fight against a bill that completely revamped state water agencies. “You can’t throw a skunk in the room and pass a law saying it doesn’t stink,” he said of the new plan. But he couldn’t follow through. His objections turned out to be procedural, to the very idea of something new rather than to what was being proposed, and the status quo he was defending was a proven turkey. Oratory notwithstanding, he fell ten votes short. In the aftermath another combatant summed up the trouble with Gerald Geistweidt: “He doesn’t like anything. Why is he here?”

Glenn Kothmann

57, Democrat, San Antonino

A monument to the indifference of the people of South San Antonio, who have endured nonrepresentation in the Senate for fourteen years. On the Worst list for the sixth time in seven sessions; hasn’t changed an iota since the first, when we wrote, “Described in the official Senate biography as ‘a man of quiet initative.’ The initiative is imperceptible; the quiet is surely for his own protection.”

Ought to be required to wear a Post No Bills sign. Didn’t pass any, which is hardly a surprise, since he didn’t introduce any. One poor House member, incensed that Kothmann had blocked his noncontroversial bill in the Senate, waited for weeks for a Kothmann bill to come through the House so that he could return the favor. He’s still waiting. Users of the legislative computer who tried to call up Kothmann’s program kept getting the notation “Not Found”—a metaphor for his entire career.

An easy mark for capitol wags. “If there was a no-pass, no-play rule in the Senate, Glenn Kothmann would have been on the sidelines long ago,” said one. “The less said about Kothmann the more accurate it is,” said another. Once Kothmann, who never has anything to say in committee, burped audibly during a committee hearing. “Will the senator yield?” asked a colleague.

Still lazy after all these years. Recruits other senators to pass House bills affecting his district, then flees to the Senate lounge lest a stray question come his way. Even recruited a House member to explain a local bill in committee so he wouldn’t have to do it. Never participates in debate; spends his time on the floor signing letters and talking on the telephone.

His pledge to vote for a controversial bill had to be devalued like the peso. Served up waffles and flakes like a boardinghouse breakfast; the Kothmann segment of the last-night Senate staffers’ slide show featured as background music “First you say you do, and then you don’t/And when you say you will, that’s when you won’t/ You’re undecided now, so what are you gonna do?”

Kothmann did have one thing on his agenda this session: trying to decide whether to run for reelection in 1986. When a potential opponent passed to the Senate a badly needed bill creating three new Bexar County courts, Kothmann malevolently sidetracked it, not once but twice, to a House-Senate conference committee—on which, true to form, he declined to serve. After the session, Kothmann announced his decision—he’s not running. The only question is, Why has he ever run?

Jan McKenna

36, Republican, Arlington

To comprehend McKenna’s passage through the 69th Legislature, imagine the worst driver you ever saw on the freeway. Right—the one switching lanes, honking the horn, lagging and speeding, hitting and running, heedless of the rules. That’s our Jan: a multicar legislative accident looking for a place to happen, a deadly combination of malice, ignorance, and arrogance.

Specialized in the three M’s: meddling, misleading, and mucking up. So pathologically partisan—she once told a colleague, upon learning at midsession that he belonged to that other party, “Oh, and you seemed so nice” – that even other Republicans loathed her. Anointed herself judge and jury of party purity, then played more-Republican-than-thou, berating comrades for votes she deemed wayward. Asked a fellow Republican how he stood on horse racing, saying that her poll was purely personal. It wasn’t. When the poor fellow said he favored it, she informed churches back in his district and goaded them into a calling frenzy. After he told her off, she began soliciting candidates to run against him. Rejoiced another Republican after a similar encounter, “she’s not speaking to me, thank God.”

Exhibited as much grasp of issues as the squirrels on the Capital lawn. Squabbled with other members over who had the territorial rights to reforming pornography laws. Won permission from Criminal Jurisprudence Committee chairman Terral Smith to introduce the same pornography bill he had labored over last session, but procured the wrong draft; proceded to cut and paste it into monstrosity, removing anything she didn’t understand, which meant there was a ton of white space; produced a bill that among other omissions inadvertently legalized bestiality, then blamed the Legislative Council for the messy draft. Caught again—the council’s code numbers, which everybody in the Capital knew about but McKenna, were conspicuously absent.

Nowhere did she play the cockroach to more damaging effect than on abortion. Hunted high and low for bills onto which she could tack antiabortion amendments, like someone playing pin the tail on the donkey. Clung to the back microphone like a barnacle, defending her cause with gems of illogic: “If it’s unnecessary, if it’s not needed, let’s put the amendment on.” Thought it clever to attach an antiabortion amendment to a liberal bill that she opposed, but days later screamed bloody murder when others tried the same ploy in hopes of luring conservatives to support another bill that she opposed. “I’m as pro-life as anyone,” a senior member told her, “but you’ve set abortion legislation back three sessions.”

Last session McKenna attributed her presence on the Ten Worst list to freshmanitis. It didn’t wash then, and it doesn’t wash now. A floor exchange with Houston Republican Milton Fox is the epigram for McKenna’s dreadful career. Fox: “Did you introduce this bill at the request of someone in your district?” McKenna: “No, this is something I thought of myself.” Fox: “I’m afraid that’s what concerns me.”

Robert Saunders

39, Conservative Democrat, La Grange

Like a medieval pope, launched crusades against the infidel to recapture the Holy Land, and plunged everything around him into chaos. Schemed and plotted to restore orthodoxy to the Texas Department of Agriculture and put heathen Commissioner Jim Hightower to the sword, pillaged and plundered anyone who stood in his way, but in keeping with the fate of earlier crusaders, succeeded only in bringing discredit to his cause.

With his bunched-up shoulders and farm-boy blond hair, Saunders seemed molded for his job as chairman of the House Agriculture and Livestock Committee. But it wasn’t his looks that endeared him to the notorious lobby clique—the Farm Bureau, the Chemical Council, the growers, the co-ops—that regards itself as the agricultural establishment. It was his zeal to serve their power struggle with Hightower the way a tractor serves its driver: unquestioning, unrelenting, its only duty to go where it is pointed.

Headed straight for Hightower’s budget. Let agricultural chemical lobbyists help write an alternative version that would have done Draco proud; it eliminated the jobs of top aides involved with the environment and pesticides, gutted the pesticide regulation program so noxious to the Chemical Council, even dictated how employee business cards should read. Saunders’ budget so crippled the agency the Speaker Lewis, no admirer of Hightower, intervened to force a compromise.

Round two: hatched the session’s most nefarious plot in an effort to undo Hightower’s ability to regulate pesticides. Refused to abide by a Senate compromise agreed upon by Hightower and his adversaries; substituted his own bill that shifted authority to a new board on which Hightower would be perpetually outvoted, then plugged his rendition as the real compromise, leading a committee member to observe, “It’s a compromise between those who want to hang Hightower and those who want to tar and feather him.” Late in the session Saunders lost a point of order that delayed floor action on his substitute for two days, during which he amused himself by killing the bills of members who opposed him. They began to retaliate; the session seemed on the verge of falling apart. On the morning of the vote, a Chemical Council lobbyist asked a respected Republican to help Saunders and was told, “You’ve been too sneaky and too greedy.” When the vote came, the House agreed.

None of that should be construed as a defense of Jim Hightower. He brought many of his troubles on himself by his thinly concealed contempt for the Legislature and his ill-judged decision to install as his marketing director a talented woman who also happened to be his live-in girlfriend. But the battle with Hightower was not over personalities or budgets or pesticides but over power: whether the good-ol’-boy network and the agricultural lobbies could mortally wound the first agriculture commissioner who was not beholden to them—a description that could never be applied to Robert Saunders.

Ralph Wallace

35, Democrat, Houston

A happy bumbler whose erratic flounderings cast him from the sea of mediocrity onto the perilous shores of the Worst list. Incapable of thinking issues through, he introduced legislation not so much by design as by accident. At the request of a constituent, carried the session’s worst bill, a measure that would have gutted the holy Texas Open Beaches Act; when warfare broke out at a committee hearing, admitted he probably should have read the bill first. Then faced the ultimate humiliation of having to beg fellow members to kill his own bill.

Had no more idea of the big picture than an ant in a redwood forest. Case in point: his gyrations on handgun law, a classic performance that mde the best case for his unlikely nickname, “Disco Ralph.” First proposed a bizarre bill under which a tax on gun sales would be dedicated to the arts; the Ways and Means Committee tabled it right in front of him, denying him even the normal courtesy of sending it to subcommittee. Oops, maybe that gun bill had been perceived as too liberal. So Ralph made a power drive to the right, introducing a bill to allow every man, woman, and child in Texas to pack heat. Oops, now the other side was mad, particularly when Wallace told a committee that “every back man in Houston carries a gun.” Spent the rest of the session trying to explain what he really meant.

For all his meandering, displayed an uncanny and unbecoming sense of direction when it came to the lobby. His single, ill-disguised aim: to run for railroad commissioner someday. Laid the groundwork this session by trying to cultivate big-bucks Houston bankers, telling them he had a lock on the chairmanship of the Financial Institutions Committee (he didn’t) used that putative chairmanship as a fundraising ploy in his reelection campaign, shamelessly sending out solicitations emblazoned with a quotation from powerful Houston banker Ben Love.

When he wasn’t with the lobby he loved, he loved the lobby he was with. Named instead to the chair of the lowly Cultural and Historical Resources Committee, he ingratiated himself with the tourism folks without missing a beat. Shortly before voting on the tourism budget, coaxed his committee into a grueling three-day, multi-city, industry-sponsored circuit of Texas tourist attractions that detractors dubbed the Magical Mystery Tour. Always too enamored of penny-ante legislative perks, he plunged gleefully into a whole new world of freebies. Soon was distributing passes to almost every theme park and tourist mecca in the state—a nifty follow-up to his ritual distribution of oil derrick neckties, an annual event by which Wallace contrives to shake the hand of every member of the House and Senate. “That’s what you have to do to get ahead,” he once told a lobbyist. “That’s how you move your legislation.” Ralph, we hate to be the ones to tell you-and after five sessions, we shouldn’t have to—but it ain’t that easy.

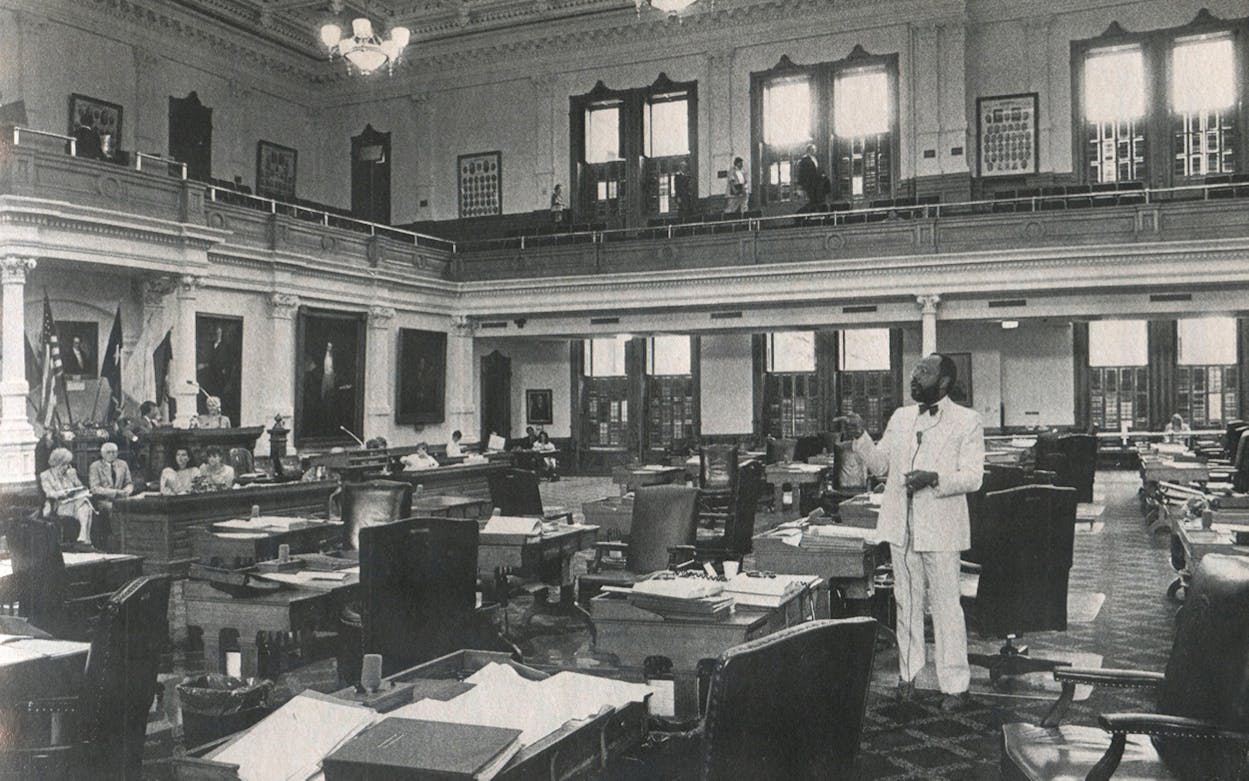

Craig Washington

43, Democrat, Houston

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Washington, one of the most brilliant and respected members the House has ever known, shouldn’t have become the stuff of Senate jokes. Question: “Where’s Washington on this issue?” Answer: “In Houston.” The laughter is sad and nervous; no one seems prepared to accept that Washington, now in his second session, has sunk from first-rate to fifth-rate, an indifferent absentee who only sporadically rouses himself to effectiveness.

That’s the essence of the Washington dilemma: there is no in-between. It’s his way or no way, as he demonstrated on the horse-racing issue in a play that symbolized his whole approach to Senate life. A cosponsor of last session’s almost-successful pari-mutuel bill, insisted anew on reserving part of the state’s take for welfare—badly misjudging the depth of this session’s fiscally conservative mood. When Hobby and fellow senators balked, he vowed to kill horse racing in the House, setting the stage for its ignominious defeat.

Did he really care more about welfare than about horse racing? If so, why in the session’s waning hours did he try to slap a dog-and-horse-racing amendment on the indigent health care package so vital to his urban black constituency? Had Hobby not quashed this ill-conceived ploy on a point of order, the back-door move would have imperiled the health care plan in the House.

Repeated the flip-flop on abortion. First threatened to filibuster if an abortion amendment went on a bill; later proposed that it be added to the exact same bill. Was the reason for his about-face a change of heart? No. A compromise? No. Just a silly game—a chance to embarrass a House member he didn’t like. Said an unashamed Washington, “I don’t like the abortion amendment, but I like to see Brad Wright squirm even more.”

To the despair of his former admirers, Washington came late to committee or left early; often he didn’t come at all. Spent more time tending to his troubled Houston law practice than he did at the Capitol. Unwilling to adapt to Senate dynamics; might as well have worn sandwich boards proclaiming “Not a Player.” Schooled in the swirling alliances of the House floor, he was reluctant to go one-one-one in clubby Senate fashion; alienated heavies like Grant Jones, whom he sneeringly interrupted in a committee contretemps. Even when he won, as when he softened the state’s wiretap authority, he was flying solo, filibustering.

Came to life in the final weeks of the session with a slew of floor amendments, bill tags, and filibusters—all one-man shows, of course. Ultimately showed he could dazzle 10 per cent of the time, but two weeks of something and eighteen weeks of nothing is enough to land any senator on the Worst list. Mourned one erstwhile fan, It’s like putting a million dollars in a non interest-bearing account.”

Ron Wilson

31, Democrat, Houston

Bad legislators fall into three classes: those who have no talent, those who have talent and don’t use it, those who have talent and misuse it. The third category is by far the worst—and the most tragic. Ron Wilson has the intelligence and the instinct for how the process works to be a major force in the House. But the right ammunition is of no use when it is always fired at the wrong targets.

Knew the arcane House rules better than any other member-clutched them under his arm in a blue loose-leaf binder as he wandered the floor-but used them to show off rather than as they are meant to be used: to police wrongdoing and affect policy. Clobbered an uncontested landlord-tenant bil with a point of order about some incorrect underlining. Delighted in taunting freshman who made routine motions to suspend the rules; toyed with them by asking for the name and number of the rules they were trying to suspend. But random shots can be ricochet. After Wilson knocked a package of nine uncontested bills off a hurry-up calendar with another purely technical point of order, he learned that the bills had been sought by Houston power broker (and occasional Wilson benefactor) Walter Mischer. “Why didn’t you tell me?” Wilson demanded of a colleague. “Why didn’t you ask?” came the reply. The ensuing delay in passing the bills cost Mischer’s business $300,000.

His own agenda was all symbolism (making Martin Luther King’s birthday a state holiday, excoriating South Africa), no substance. Attempted to graft anti South Africa amendments onto anything and everything, which sounds harmless enough, except that Wilson—whose bill package is pitifully meager—finds so little time for legislation that might actually help his urban constituency.

The sad part was that since Craig Washington’s departure from the House, Ron Wilson was the closest thing to a leader the black members had—and he let them down. As a member of the powerful Calendars Committee that scheduled bills for debate, he failed to help other blacks get their bills heard; indeed, he was mostly a no-show. He split the Black Caucus in two with his insistence on piece-of-the-pie politics that helped kill the horse-racing bill. He has led by example, but it was the wrong example. Hispanics, once far behind blacks in the house packing order, now are far ahead, mainly because they eschew the tactics espoused by Ron Wilson. His time has passed, his only legacy the dying words of Willie Stark in All the Kings Men, that it all could have been different.

Special Awards

Clarence Darrow

Excellence in Debate Award

Senator JOHN WHITMIRE, Houston. Offered to pass an amendment to add pleasure boats to the list of property (like homesteads) that is exempt from court foreclosures. “Is anyone in the state of Texas for this amendment?” asked an incredulous Senator Bob Glasglow. “Me,” replied Whitmire.

Sydney Carton

Memorial Award

As Dickens wrote, “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known.” To Senator LINDON WILLIAMS, Houston, who after a long and undistinguished career, gave up his seat to become a lowly (but well-paid) justice of the peace.

Honorable Mention

Pity JOHN MONTFORD (Conservative Democrat, Lubbock), the hardworking Senate sponsor of the water plan. No one should have to had to spend so much time with that awful quintet the House sent to negotiate the final package. Their inflexibility sabotaged Montford’s chances of making the Ten Best list; gave him a Purple Heart instead. The rest of the second ten, all of them House members:

Lloyd Criss, Democrat, La Marque

Bruce Gibson, conservative Democrat, Cleburne

Juan Hinojosa, Democrat, McAllen

Lee Jackson, Republican, Dallas

Ray Keller, Republican, Duncanville

Pete Laney, Conservative Democrat, Hale Center

Frank Madla, Democrat, San Antonio

Jesse Oliver, Democrat, Dallas

Jack Vowell, Republican, El Paso

Dishonorable Mention

Of all sad words of tongue or pen, the saddest are these: “Is Mr. Hudson on the floor of the House?” When that question booms out over the House speakers, you can bet that another important piece of legislation is in jeopardy because SAM HUDSON (Democrat, Dallas) has missed a crucial vote. Two years ago his absence was fatal to the horse-racing bill. This year he missed the key vote on indigent health care during the special session, even though it was probably the most important vote for his South Dallas constituency that he will ever be called upon to cast. Only a tie-breaking vote by Speaker Lewis saved the bill—and Sam’s hide.

How bad was KELLY GODWIN (Republican, Odessa)? The folks back home had to hire the fellow he defeated as a lobbyist in order to get representation. His problem: hypocrisy. He begged for more state spending in his district (home of much-beleaguered UT-Permian Basin) but when it came to raising the money to pay for it, Godwin was an unrepentant no.

Best Nickname

“Grunt” Jones. For GRANT JONES of Abilene, chairman of the all-powerful Senate Finance Committee. Jones mastered a mumble that was perfectly clear to his committee underlings, though remaining inaudible to an audience of bureaucrats and lobbyists desperate to learn what was happening to their pet projects in state budget.

Furniture

The term “furniture” first came into use around the Legislature to describe members who, by virtue of their indifference or ineffectiveness, were indistinguishable from their desks, chairs, and spittoons. It is now used, casually, and more generally, to identify the most inconsequential members. Our furniture list for the 69th Legislature:

New Furniture

Bill Blackwood

Bill Carter

Eldon Edge

Ron Givens

Used Furniture

Talmadge Heflin

Don Lee

Paul Hilbert

John Whitmire

Squeaky Furniture

Pete Patterson

Al Price

Irma Rangel

Antique Furniture

Tony Garcia

Sam Hudson

Lou Nelle Sutton

Petrified Wood

Charles Finnell

Boss of the year House Division

Charles “Goose” Finnell, Holliday. Asked his staff out to lunch and informed them that they would all have to take a large cut in pay. Then he made them pay for their lunches.

Boss of the year Senate Division

Carlos Truan, Corpus Christi. Immediately after Truan passed his bill to guarantee teachers a duty-free lunch period, one of his aides contended that she was fired for taking a full hour for lunch.

Best Observation

Bill Finck, Lobbyist, San Antonio

Perusing a copy of bills scheduled for debate that day, Finck said, “You know, the Republic has survived for a hundred and fifty years without a single one of these bills becoming law.”

Most Improved

Senator John Leedom, Republican, Dallas

A worst just four years ago as the Senate’s abominable no-man, Leedom has become a valuable member of the Senate. He has accentuated the positive side of his conservatism by finding ways to save money for the state that no one else even dreamed of. Just how far he has come was evident during the special session, when he went to the House to urge Republicans not to kill indigent health care. Said Leedom: “There’s a difference between being conservative and being stupid.”

Best Columnist

Anne Cooper, Republican, San Marcos

In a world where everything gets magnified, especially one’s self-importance, Cooper’s reports from the field had a refreshing human quality. Our favorite excerpt:

“Some of the letters [on the horse-racing issue] were quite strongly worded, but the threats dealt only with my possible reelection and not with my life, so that was a relief. Next time we have a really controversial issue, I hope someone who doesn’t care one way or the other will drop me a note to that effect.”

H. Ross Perot Back to Basics Award

To Austin representatives BOB RICHARDSON, who missed every subcommittee meeting of the Department on Aging budget and then angered colleagues by going over the budget line by line in full committee, question even the most paltry increases. Finally reaching the line that marked the grand total, he demanded, “Why is this increase so much greater than any of the others?”

Dumbest Argument

Betty Denton, Waco.

Jumped into a heated debate over teacher competency tests, a crucial part of last summer’s education reform package, to argue that the tests should be eliminated because they had been written by “an out-of-state, Yankee company.”

Smartest Argument

Bill Hammond, Dallas

Following Denton at the microphone, Hammond quickly responded, “That’s probably the most ridiculous reason to be for or against this proposition.”