THE ANCIENT GREEKS BELIEVED THAT politics was the art of organizing and governing human society for the greatest good, and considered it to be among the highest callings of man. Since that time, politics has sunk somewhat in public esteem. Some cynics claim that there are two things one should not watch being made: hot dogs and the laws of the land.

We watched the laws of our state being made during the 63rd session of the Texas legislature; and while the legislators could hardly pass for ancient Greeks, they were much more noble than those of us who automatically write off politics and politicians would like to think.

Teddy Roosevelt once said that good men must enter politics or else be governed by those who do. This session of the legislature provided a cast of characters that included some noteworthy good men and some of the other kind. There were honest and dishonest men, conscientious workers and utter charlatans, plodders and posturers, scoundrels and statesmen. In short, the legislature was a lot like us, like Texas. It was amazingly diverse and boringly predictable; grand and generous and mean and small.

The legislature is the best entertainment Texas has to offer. One can picture in the galleries the shirt-sleeved crowds fanning themselves in the unairconditioned heat of earlier Texas springtimes, images from an era when politics was entertainment. Before movies, radio, and television, politics was the only show in town. Texas politics is still a great crowd pleaser. It’s the honorable this and the worthy that and will the gentleman yield and the whole ritual that organizes conflict into resolution while keeping it from getting, hopefully, too personal.

When it comes down to it, though, the business of governing Texas is a personal business. Politicians work with each other under intense pressure and through long hours; it’s the sort of work that brings out the best and the worst in people.

To find the best and worst we took our pads and pencils and watched the legislature, watched it from the gallery and watched it in the committees where the key work is always done. We talked for a month with people who knew the politicians, who saw them under pressure: the press, the lobbyists, the staff, the academic scholars, and especially the members themselves, who often are the most discerning judges of the men and women who share their battles in the legislative pits. The sketches which follow represent a composite portrait of some of the people who write our laws, a portrait gleaned from the insights of those who work with them every day.

The sheer size of the Texas House of Representatives (150 members) and its tendency to herd-like behavior reduce the opportunities for individual members to display their best qualities (although the opposite is not true: the worst members are painfully obvious). The Senate, because of its intimate size (31 members) and calm, parliamentary atmosphere, offers a better setting for each member to exhibit his potential.

In addition to the Ten Best Legislators, several members deserve an Honorable Mention award. The Senate is particularly well-stocked with contenders. Bob Gammage, 35, a freshman liberal Democrat from Houston, carried one of the largest legislative programs in the Senate (including a number of controversial measures like portions of the Speaker’s reform package, consumer protection, and the eighteen-year-old rights bill), fought for it in the rough-and-tumble tradition of Babe Schwartz, and got much of it passed. Tati Santiesteban, 38, a liberal Democrat from El Paso who served three terms in the House, showed exceptional ability in floor debate as the sponsor of the complex Penal Code and (with Jim Wallace) the Senate drug legislation; he quickly acquired the admiration and confidence of senior members to a degree rarely accorded to newcomers. Jack Hightower, 46, a conservative Democrat from Vernon and an old-line member of the Senate establishment, performed his duties as chairman of the Administration Committee with rock-solid fairness; he continues to be among the most trusted and respected Senators, in spite of the defeat this session of the major item in his legislative program—the oil field unitization bill. Oscar Mauzy, 46, a liberal Democrat from Dallas, was a tireless work-horse with a huge legislative program and a high degree of effectiveness. Chet Brooks, 37, a liberal Democrat from Pasadena, came into his own this session, particularly in the area of appropriations.

In the House, Fred Agnich, 59, leader of the Republican delegation from Dallas, helped to make his party a credible force in the legislature for the first time in a century and lent strong support to environmental legislation. Walt Parker, 55, a conservative Democrat from Denton, won wide admiration from his fellow members by dint of his hard work on appropriation matters; his effective presentation of welfare appropriations was a notable example of his ability to understand and deal convincingly with complex new problems. Carl Parker, 38, a liberal Democrat from Port Arthur, showed considerable poise and forcefulness as one of Price Daniel, Jr.’s chief lieutenants. Dave Finney, a conservative Democrat from Fort Worth, gained in stature and articulated a thoroughly urban-oriented point of view on such issues as redistricting, drug law reform, and school finance. Robert Maloney, 40, a freshman Dallas Republican, was probably the new member most respected by the lawyers in the legislature; a former prosecutor with a razor-sharp intelligence and enormous presence in floor debate, he has a bright future. Gene Jones, 28, a liberal Democrat from Houston, and Buddy Temple, 31, a moderate Democrat from Diboll, were alert, effective, and usually capable freshmen whose careers seem only beginning.

Billy Williamson, 45, a conservative Democrat from Tyler, took purposefully preposterous stands on most public issues but served an indispensable function by adding an ingredient of good humor to debates; his quick wit was displayed throughout the session, but to best advantage on the final night, when the important school finance bill dead-locked on a 70-70 tie vote. Speaker Price Daniel, Jr. did not cast his potential tie-breaking vote immediately but retired to his office for 20 minutes to confer with his lieutenants. When he returned he declined to vote, thus gavelling the bill dead. Williamson broke the tension by stepping to the microphone and asking, “Mr. Speaker, were you able to get the Supreme Court on the telephone?”

THE TEN BEST

Six Representatives and four Senators are among the Ten Best Legislators. They are discussed in alphabetical order. Speaker Daniel (who proved that it was possible for the House to function democratically) was excluded from consideration because the presiding officer’s role is fundamentally different from that of an ordinary member’s and cannot be judged on the same terms.

Neil Caldwell, 43, Liberal Democrat, Alvin. Probably the all-around best member of the legislature, on every list of “The Ten Best.”

Acquired power for the first time this year, replacing Bill Heatly as chairman of the all-important Appropriations Committee; conducted himself brilliantly and produced one of the best appropriations bills in years.

An extremely smart, savvy politician who is thoroughly trustworthy. Treats public office with the outtmost seriousness without being sanctimonious about it. Realized early in his career that a sense of humor could do more than anything else to preserve his effectiveness without forcing him to sacrifice his principles; has honed the art to perfection. (A few days after Fred Agnich, last session’s leading Republican member of the “Dirty 30,” had successfully gutted the financial disclosure bill, he was defending his conservation-oriented endangered species bill on the floor of the House. Caldwell offered a tongue-in-cheek amendment adding “Republican Reformers” to the list of creatures threatened with extinction.)

One of the most versatile men ever to sit in the Texas legislature—an accomplished musician, cartoonist, sculptor, and motorcyclist.

DeWitt Hale, 56, Moderate Democrat, Corpus Christi. Old-line, establishment House member who in some ways is himself the House establishment, having seen numerous speakers come and go during his 11 terms. Could have let his ambitions carry him up and out of the House as most capable young members do; instead, has stayed around year after year and devoted his energies to building the House as an institution.

Has had a significant impact on the public policy of the state, mostly for the good. With his grandfatherly manner and hard work, has influenced the House rules more than any other member. An expert parliamentarian.

Questionable record on some smaller and middle-sized issues (e.g., loan sharks, homebuilders), but has a good grasp of what the really important issues are and what he should do about them. Gets there without a trace of idealism in his makeup, however.

Carried the judicial reform package in the House this session; ran afoul of the traditional House reluctance to interfere with established interests, in this instance the court bureaucracy, and lost badly. Nevertheless continues to be one of the formidable forces in the legislature.

Ray Hutchison, 40, Republican, Dallas. Best of the Republicans, and a fine member by anyone’s reckoning. Has won the respect of his colleagues to a degree achieved by few legislators, and by almost no freshmen. Phenomenally effective for a first-termer: almost any time he offers an amendment on the floor, he gets it on.

Represents the wishes of his conservative North Dallas constituency loyally while retaining an open mind to rational argument by those who disagree. Almost single-handedly killed two of the most important pieces of environmental protection legislation offered this session (HB 205 giving citizens the right to sue state agencies to enforce pollution control standards, and HB 646 creating a State Office of Environmental Quality), while retaining the friendship, admiration, and respect of his opponents in the process.

Significant accomplishments: fought like a tiger to secure appropriations for education of deaf children; pushed through a proposed Constitutional amendment (SJR 29) which would improve credit ratings of Texas municipalities and save taxpayers $40 million a year in bond interest charges.

Like several other Dallas Republicans [see Honorable Mention list], he symbolizes an increasingly urban and urbane trend among conservatives, in a marked contrast to the sputtering ineffectiveness of the doctrinaire Houston wing of the party. More like a good legislator from California, Oregon, or Connecticut than the sort Texans have been accustomed to seeing over the years.

Dan Kubiak, 35, Moderate Democrat, Rockdale. The best-educated chairman of the House Education Committee in recent history. The only man in the House, except DeWitt Hale, who really understands the complex issues of education and school finance which account for 47 per cent of the entire state budget. As the only member who is capable of actually writing education bills himself, his expertise is invaluable. Has two years to develop a new school financing plan; his success on this could make or break his political career.

Closely allied to the teachers’ lobby (Texas State Teachers Association), but has the rare ability to go beyond his base of support to influence the attitudes of those who seek to influence him (an example: his no-nonsense approach to the 1976 teacher pay raise, which the TSTA sought to obtain but which would have wrecked the school finance bill).

A diligent, hard worker who attends committee meetings, keeps informed, knows what is going on. Incorruptible, though critics complain of occasional doubletalk.

Like Caldwell, a man of wide-ranging, cultivated interests. Historian, newspaper publisher, author of highly-regarded books on Texas.

Bill Meier, 32, Conservative Democrat, Euless. One of the happiest surprises in the current Senate. A freshman with no prior political experience, he is one of its best-informed and best-intentioned members.

Most distinguishing characteristic is a painstaking attention to detail that never descends to nitpicking. Catches points that other Senators miss in their haste to thresh out the major policy issues in a bill; a legal craftsman.

Probably somewhat more conservative than his district, but never dogmatic. Highly accessible, open-minded. Unfortunately was a key vote to kill the Telephone Utility Commission; strongly involved in criminal law legislation, sometimes on the conservative side (death penalty, oral confessions), sometimes on the liberal side (marihuana). Played a major role in salvaging the House reform legislation in the Senate; did an outstanding job as sponsor of the campaign finances disclosure bill (HB 4).

Nothing special in floor debate but absolutely outstanding in committee.

Hawkins Menefee, 28, Moderate Democrat, Houston. One of the brightest of the 77 freshman House members, with an impressive command of the Texas political process gained in his work as a legislative aide and member of the Southwest Center for Urban Research in Houston.

Strongly urban oriented, he emphasized environmental issues, mass transit, and consumer problems in his legislative program and met with moderate success in achieving his goals. Intelligent, ambitious.

Won a key seat on the Appropriations Committee and became known for his skill at political maneuvering. Served on the House-Senate Conference Committee on the appropriations bill, a rare and powerful position for a freshman. Worked behind-the-scenes to preserve key measures, such as the food stamp program.

Very sophisticated in his approach to politics and to other politicians, he is willing to put in long hours lobbying other members on behalf of his bills.

In manner a trifle too slick for some, a little too down-home for others. Perhaps the most talented mimic in the history of the legislature; his ability to use humor took some of the edge off a tedious session.

A.R. “Babe” Schwartz, 46, Liberal Democrat, Galveston. The most complex, remarkable man in the Senate. Came to the legislature in 1954 as an all-but-ignored liberal gadfly, now one of the most consistently influential members. Votes an unabashed liberal record but always manages to stay on good terms with whoever happens to be lieutenant governor, a situation which has generated suspicion from other liberals. Has almost single-handedly saved the Gulf Coast beaches from commercial exploitation.

Picks his battles carefully. Once he decides to go after something, he is a ferocious adversary. A former prosecutor whose penetrating voice seems to come from the corner of his mouth, he is expert in floor debate, repartee, and filibusters. Even stronger in committee, especially conference committees, where the mere presence of his name on the list of Senate conferees is enough to strike terror in the hearts of the House contingent. Often spreads himself too thin, especially at end of session when he tries to carry the ball in several conference committees meeting at the same time. When present, a master of the divide-and-conquer technique.

Quick, phenomenally retentive mind. Brilliant understanding and insight into the most complex matters. A gut-fighter by instinct, has nothing of the goody-goody in him; has no use for the “Scholz’s Liberals,” who reciprocate the disdain. Likes power and is willing to accept the down side of things occasionally to keep it. Tied to Galveston millionaire Shearn Moody long and closely—in the opinion of many observers, too long and too closely. Not for sale, but remains a complete cynic about politics and the possibility of “political reform”—an attitude which may help to explain his prolonged, bitter feud with Senator Bill Patman of Ganado, himself a model of scrupulous personal rectitude. Accept others’ frailties (except Patman’s) and makes no excuses for his own.

Max Sherman, 38, Conservative Democrat, Amarillo. Rates high in honesty and intelligence. A person of great integrity who takes his job seriously and has a genuine sense of public service. More nearly resembles a thoughtful professor of business administration than the popular stereotype of a politico.

Makes an earnest effort to be well-informed, a rare trait in any case and one which few legislators can sustain through the heat of a session. A “floater,” not locked into a preconceived ideological position. His very open-mindedness increases his influence and helps him swing votes. Regarded as totally fair, even by observers who don’t agree with his positions as chairman of the important Natural Resources Committee.

Legislative program is rather modest. Reluctant to carry controversial bills; on the other hand, is not one of those legislators who is a soft touch for seamy-sided special interest legislation. A stabilizing influence on the Senate.

Represents the most isolated, homogeneous district in Texas, an area which usually prefers to be left alone and often sends legislators to Austin to accomplish that purpose. Like Representative Dean Cobb, Dumas, Sherman is a conspicuous exception to this rule, taking an interest in problems that affect the entire state.

Jim Wallace, 45, Moderate Democrat, Houston. Splendid senator, probably the best of the lot. A quiet, polite Baptist teetotaler, the polar opposite of a flamboyant demagogue. Moves slowly and deliberately but always knows exactly what he is doing. An observer in the Senate gallery would never surmise the breadth of his influence from watching him on the floor.

Like Sherman, works hard at being well-informed, and succeeds. Much of the respect he has in the Senate is due to the fact that he is a man of absolute courage who is never rash. Would clearly rather not be a Senator at all than be a phony Senator or a bad one. Unimpeachably honest. Like Schwartz (and Mauzy and Brooks), is one of the few legislators who recognize the importance of hiring a capable, professional staff and making intelligent use of them.

Has a substantial and carefully-thought-out legislative program, emphasizing environmental issues. Was sponsor of every major piece of environmental legislation that passed the 1971 and 1973 legislatures (other than Agnich’s endangered species act and Schwartz’s coastal laws), including improved standing-to-sue in pollution cases and full agency status for the Air Control Board. Also carried Title III of the new Family Code, improving the handling of juvenile delinquents, and the Senate version of the marihuana and drug reform legislation.

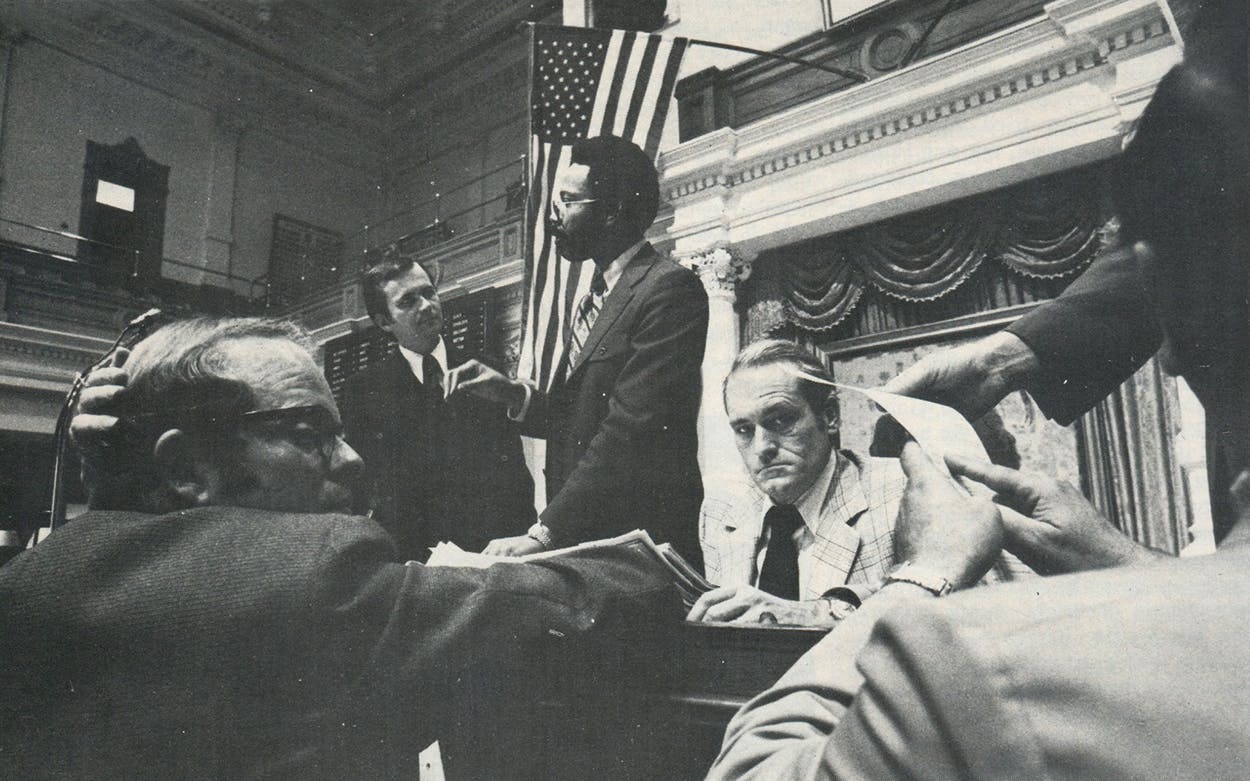

Craig Washington, 31, Liberal Democrat, Houston. Has done more than any man in history to end racism on the floor of the Texas House.

Vigorously represents the interests of his predominantly-liberal constituency, which includes the University of Houston and Texas Southern University.

Has a remarkable facility for expressing his controversial views without antagonizing the more conservative members. Fought the death penalty bill (HB 200) with a sureness of parliamentary technique and some of the most moving oratory to be heard on the House floor this session. Has a gift for focusing (and forcing others to focus) on the crux of a problem instead of the peripheral issues.

Not always punctual in tending to his committee assignments, but resourceful and quick-witted on the floor and a formidable opponent when he gets down to business.

Mesmerized House members with a personal privilege speech delivered after midnight at the close of the session on May 28:

“From a poor boy across the tracks, you cannot possibly know what it means for me to stand here with you. If we understand each other, then you tell the poor little black boy who still lives across the tracks and the poor little white boy who still lives across the tracks that they can be here too…Go home and tell the people we didn’t do all we wanted to, but we tried.”

Has announced he will not run for reelection in 1974 because of an inability to make financial ends meet on the $400-per-month salary a representative is paid.

THE TEN WORST

The following list of the Ten Worst Legislators contains eight Representatives and two Senators. They are listed in alphabetical order.

“Jumbo” Ben Atwell, 57, Conservative Democrat, Dallas. Chairman of the House Revenue and Taxation Committee under the ancien regime where he was put in the hands of the corporate lobby; now completely without influence. Reduced to cavorting around the House as a kind of brobdingnagian court jester (he arrived one day this session wearing a necktie the size of a Navajo blanket; members ho-ho-ho’d as cameras clicked, then winced as constituents’ letters poured in demanding to know why the hell the legislature didn’t have better things to do with its time.)

Personally beloved by almost every member, but few take him seriously. The classic surviving example of the “good ole boy” syndrome. Unlike Billy Williamson, his form of comedy serves no useful function because it doesn’t relieve tensions in the legislative process, but instead mocks it.

Microscopic sense of public responsibility. Just enjoys being in Austin, and the Dallas Establishment keeps finding reasons sufficient unto themselves for sending him back. If missing from the Capitol, can usually be found at the Deck Club.

Charles Finnell, 29, Conservative Democrat, Holliday. Nicknamed “Zero” by his colleagues, a reference to their estimate of his intelligence. A sheep in peacock’s clothing. Spend more time preening himself than he does reading bills, seems to have no guiding principle except self-admiration. His omnipresent comb is one of the most widely-discussed artifacts of the session.

Remarkable for his lack of candor.

In past sessions he usually waited to see what Bill Heatly did before pushing his own voting button; with Heatly’s demise this session, has had a hard time figuring out whom to follow.

The consensus choice for “most insufferable” member of the House.

Glenn Kothmann, 45, Liberal Democrat, San Antonio. Described in the official Senate biography as “A man of quiet initiative.” The initiative is imperceptible, the quiet is surely for his own protection. Easily the densest member of the Senate. People still cannot imagine how he got elected, much less reelected.

An object of derision by other Senators. “Let Kothmann carry that bill on the floor,” one remarked to another during a lull, “so we can watch him try to explain it.” Whenever he was entrusted with the chair by the lieutenant governor, parliamentary proceedings seemed to grind to a mangled halt.

So happy to be a Senator that he can’t find time to be one. Would probably let his secretary vote for him, as he did in the House, except that the Senate requires voice votes. Has no legislative program of any consequence and seems proud of the fact. Passed only five bills, all strictly local. The lobby regards him as an easy mark. Despite his liberal-labor stereotype, he provided the crucial fifth vote that killed the telephone utility commission bill in subcommittee. The only urban legislator to vote consistently with the Farm Bureau.

Exceedingly vain, as though people were noticing. Owns (and wears) what must be the largest collection of black shirts since the March on Rome.

Mike McKinnon, 34, Conservative Democrat, Corpus Christi. The quintessential media candidate—a TV-station-owner who got elected on the strength of his pretty face and the reputation of his predecessor, liberal Democrat Ronald Bridges. (Corpus has gained some notoriety for its long line of awful Senators. Nobody thought they could come up with one worse than Bridges, but they did.)

His big problem: he’s in way over his head. Frequently has to be told what to do, often by a sympathetic adversary who realizes his plight. Introduced exactly two bills all session, perhaps an all-time record low. Neither of them passed. Otherwise his legislative program consisted of a handful of simple resolutions—the usual stuff honoring hometown high school classes in the gallery, plus one welcoming Clinton McKinnon, his brother.

Earned special animosity from supporters of the newsmen’s shield bill (HB 10) by posturing as a newsman and expostulating at length why the bill was unnecessary.

Tries to make up for his obvious inability to cope with his surroundings by all sorts of picayune, petty behavior—conduct which has led other Senators to regard him as the most obnoxious member of their very exclusive club.

James Nugent, 51, Conservative Democrat, Kerrville. Most mistrusted man in the House. Perhaps also the most misunderstood, but no one knows for sure. Fine intelligence, extraordinary ability, dazzling command of parliamentary rules and procedures. Can verbally cut a member to ribbons from the back microphone. Secretive, aloof, hostile to daylight. Nobody trusts him beyond a certain point, not even his friends. Nickname: “Supersnake.”

A master craftsman—although, as Churchill once remarked, “craft is common both to skill and deceit.” Devious, sneaky, rows to his object with muffled oars. Not above using others to do his dirty work while posing as a champion of the good, true, beautiful, and whatever else he thinks the Hill Country burghers will like. Carried the ethics reform bill (HB 1), orated on the sublimity of Ethics, and is widely suspected by other members of trying to sabotage the bill with behind-the-scenes maneuvering. Has spent 13 years of public life looking for people to play Faust to his Mephistopheles.

Lindsey Rodriguez, 41, Liberal Democrat, Hidalgo. Combines aggressive ignorance, a boorish manner, and a persistent, flypaper-personality into one of the most dismaying members of either house.

Has no idea of what is going on. Said one colleague: “he actually works at being dumb.” After three terms, he still has not bothered to learn the most basic procedural rules, has been known to try to bring up bills for floor debate which have not even been heard in committee. Mystifies unsuspecting staff members and clerks, who cannot believe he is a Representative.

His support on the floor is an albatross for anything; his real damage, though, is done in committee. Will sit quietly while others reach a decision, then pop up with totally unrelated and disruptive objections. Temporarily stalled a bill renaming the State Finance Building for Lyndon Johnson by demanding that the question first be submitted to the U.S. Postal Service to see what they thought about it. Consumes an astonishing amount of legislative time with petty and incomprehensible objections, apparently for the sole purpose of letting the other members know he is thinking, which he is not.

“Not only is he stupid,” said a member who has served with him for five years. “He wants everyone else to be as stupid as he is.”

Henry Sanchez, 42, Liberal Democrat, Brownsville. On everyone’s “worst” list except, presumably, his own. Has a conception of politics that bears no relation to any civics textbook. Spends a large portion of his time studying how to manipulate the special interests to his advantage.

Represents one of the poorest, most downtrodden districts in Texas, which he simply ignores once he gets to Austin for the Big Game. Opposed the minimum wage during his first campaign in 1967. Has apparently infinite capacity for the beer-and-barbecue circuit that constitutes politicking in South Texas. This—plus the fact that he is not smart enough to pose any kind of threat to the established Brownsville interests (meatcutters union, Farm Bureau, manufacturers’ association)—keeps getting him re-elected. His races are becoming closer, however: last time he won by only 114 votes over a weak Republican candidate.

An example of the lowest common denominator in South Texas politics now that Anglo hegemony has been shattered.

Wayland Simmons, 32, Conservative Democrat, San Antonio. His only goal in politics is to survive and advance himself. Blithely indifferent to any other purpose. Most frequent descriptive comments from other members: “calculating,” “common,” “vicious.”

Adorns his meager legislative program with bills designed to harass people who disagree with him or who didn’t support him in the last election. Likes to set these bills for public hearing, force his opponents to take a day off work and drive to Austin to testify against them, then cancel the hearing moments before it is scheduled to begin. (Did this with HB 846, aimed at crippling the Bexar county auditor by placing him under the thumb of the county commissioners whom he is supposed to audit. The auditor has been involved in a bitter feud with Commissioner Tom Stolhandske, one of Simmons’ law partners.)

Enjoys being an obstructionist on the floor. Took particular delight in objecting to rules suspensions necessary to ease the logjam of bills at session’s end. Pretended to support reform principles but seldom missed an opportunity to sabotage them and make them appear unworkable. A classic example of the unreconstructed Mutscherite trying to restore legislative politics to the old autocratic ways.

A shameless demagogue. Has lost credibility among his colleagues for his bald-faced misrepresentations on the floor of the House; they know he does it, he knows they know he does it, but he keeps on doing it.

Used his “legislative continuance” power to delay the felony trial of Hudson Moyer, a former Representative accused of stealing state postage stamps to payoff a note at his bank. According to Travis County District Attorney Bob Smith, who will prosecute the case, Simmons signed on as one of Moyer’s attorneys the Monday before the legislature convened, automatically forcing a postponement until July 9.

Tim Von Dohlen, 29, Conservative Democrat, Goliad. Cut from Crusader’s cloth, the sort of man who would burn an Islamic mosque in the name of God. Medieval in his rigidity, a timeless example of the zealot in politics. No sense of give-and-take, but sees politics as a morality play in which he is cast in the leading role to banish devils, a category which seems to include anyone who has a life-style different from his own.

His legislative program consists chiefly of trying to enact his prejudices into law for everyone else (a partial exception: the abortion issue, where he defended freedom-of-choice for hospital personnel). Said one member: “He’s the sort of person who’d take a bill permitting acupuncture and try to amend it by requiring that the work be performed with rusty needles.”

Resourceful, hardworking, and (like Nugent) quite intelligent. One of the few Representatives to abuse his power in this reform session: as chairman of the Public Health subcommittee he deliberately smothered a bill regulating nursing homes (HB 414) by refusing to recognize any motions to act upon it until so late in the session that it was doomed. (Fred Head of Troup tried the same tactic as chairman of the Reapportionment Committee and later apologized for his behavior on the floor of the House; Von Dohlen did not). Considered a pushover by the lobby, not because he is crooked (he’s personally honest) but because he is their natural, instinctive ally. Said one lobbyist: “If you’ve got a bad bill you want passed, just get a short-haired, clean-cut guy to take Von Dohlen to lunch and maybe offer to fly him to some high school commencement in your corporate jet. He’ll carry that bill with a smile—and the amazing thing is, he’ll never even ask you what the down side of the bill is.”

Represents the worst of Middle America—narrowness, lack of compassion—without any of its saving virtues—humor, openness, basic fairness. Said one long-time member: “He personifies everything that’s bad about Texas politics, except he’s not a crook.”

Doyle Willis, 64, Moderate Democrat, Fort Worth. One of the least competent legislators, he has fed at the public trough for much of his adult life. Lacks even elementary respect from his colleagues, who consider him a boring phony and rush for the telephone whenever they see him coming.

Viewed by many other Representatives as untrustworthy, in a blasé sort of way; they point to his tendency to play both sides of the fence in such matters as pledges for the 1975 speaker’s race. The sort of person who would fit in perfectly in Chicago, cheerfully whiling away his time with whatever Mayor Daley told him to do.

Casually indifferent to the needs of his district; never even showed up for the Appropriations Committee meeting at which the UT-Arlington item was considered, even though the university is in his district and he was the only Fort Worth area representative on the committee. Blamed for holding up the entire Tarrant County redistricting plan in hopes of wangling a seat for his son.

Used to be in the Senate (1953-1962); wants to go back. God forbid.

A LEGISLATIVE LEXICON

The legislature, like any club, has developed a descriptive language all its own. Among the more popular expressions:

cockroach, n. A member who stirs up trouble to no good purpose; “It’s not what he carries away that’s the problem: it’s what he gets into and messes up.” Not as brutally pejorative as it sounds. Rep. Tom Uher, Bay City, is the most often-cited example.

crater, v.i. To renege on one’s promises under pressure. A sudden and total cave-in. “He really cratered on that vote.”

down side, n. The unsavory aspects of a proposal. “The down side of that bill is that it would turn over the public lands to Exxon.”

flake, v.i. To drift away by degrees from a previously-stated position pledged to a colleague. “Senator, I’m down here just flaking away on that oil unitization bill.” In contradistinction to cratering, flaking may occur to enhance the flakor’s strategic bargaining position with the flakee.

furniture, n. Members of the legislature who, by virtue of their ineffectualness or stupidity, are indistinguishable from their desks, chairs, and inkwells.

L.S., n. Loan Sharks.

L.R., adj. Low-rent. Mediocre, lacking in ability, merit, or character. “Those vending machine lobbyists are really L.R.”

low-rent sumbitch, n. Very mediocre. “The honorable member from San Antonio is a low-rent sumbitch.”

on the take, adj. Receiving a bribe or available to be bribed.

Scholz’s liberals, n. Ineffectual, doctrinaire crowd of liberal members who congregate at Scholz Garten and complain about the way things are going. Rarer than it used to be, chiefly because they now congregate somewhere else.

stout, adj. Strong, effective, not easily dislodged in floor debate; often has connotations of approval of the viewpoint espoused by the member described. “That Senator Trial Lawyer from Houston is stout,” said Senator Trial Lawyer from Dallas.

topwater, n. lit., a minnow. A lightweight politician, one who does the work of the big boys; a front man for special interests. John Connally is the antithesis of a topwater.

white, adv. Refers to the electronic voting board in the House of Representatives, where a red light beside each member’s name signifies he is voting “no,” a green light “aye,” and a white light “present but not voting.” Used as a device to avoid commitment on an issue while proving to the voters back home that you were not out drinking beer when the vote was taken. “I think I’ll vote white on this ones, friends.”

FURNITURE

The term “furniture” is casually used around the legislature to describe members who have no discernible ability to grasp what is going on, and who for that reason do not participate to any significant extent in the proceedings. These members may be personally popular with their colleagues, but their impact on the legislative process is nil except when they push their voting buttons or answer a roll-call vote.

The Furniture List for the Sixty-Third Legislature:

House

Latham Boone III—Navasota

Sid Bowers—Houston

Terry Canales—Premont

Phil Cates—Pampa

Nub Donaldson—Gatesville

Tony Dramberger—San Antonio

Frank Gaston—Dallas

Forrest Green—Corsicana

Joe Hanna—Breckenridge

Joe Hawn—Dallas

Don Henderson—Houston

Joe Hernandez—San Antonio

Bill Hilliard—Fort Worth

Doyce Lee—Naples

Elmer Martin—Colorado City

T.H. McDonald—Mesquite

Joe Sage—San Antonio

Elmer Tarbox—Lubbock

John Whitmire—Houston

Senate

Roy Harrington—Port Arthur

John Traeger—Seguin

SPECIAL BEST & WORST AWARD

Best…worst…Sometimes categories fail and words fall short. Sometimes the line between a scoundrel and a statesman can be hammered too thin to recognize. Such is the case with Senator Bill Moore, 55, the bellowing “Bull of the Brazos.”

Moore is second in Senate seniority, and he has forgotten nothing in the 23 years Bryan has sent him to Austin. Few men have mastered parliamentary tactics and the art of good-humored gamesmanship as well as he; few men have so scant a legacy of significant public accomplishment to show for their skills.

His wit is legendary, his abilities immense. Without him the Senate would be a husk of its present self; with him, the Senate can bear fruit only by overcoming the impediments he places before it. He is alternately obstreperous and expeditious; he makes no effort to get along, to yield, not even to remain silent after everyone has had enough of him; yet he can call a truce in the flick of an eyelash and get the business done. His eight-year tenure as chairman of the powerful State Affairs Committee is unblemished by even the merest hint of democracy, yet no Senator holds any lasting grudge against him for unfairness or tyrannical behavior, and the job seems his for as long as he wants it. He is capable of the most blatant, disingenuous, low-down dirty tricks (as when he killed Senator Charles Wilson’s telephone regulatory bill in 1969), and at the same time of breathtakingly generous acts toward an opponent whom he discovers momentarily off balance (as when he rescued Senator Charles Wilson’s telephone regulatory bill in 1971).

He is baffling, unclassifiable, larger than life. Of him it could be said, as it was said of the nineteenth-century Irish patriot/villain Daniel O’Connell, “The only way to deal with such a man is to hang him up and erect a statue to him under the gallows.”