Brian D. Sweany: I was interviewing former state senator Florence Shapiro in 2004 when Governor Perry appointed you to be chief justice. She was thrilled when she heard the news and thought you were a terrific choice. Obviously you had already been on the Supreme Court, but take me back to that moment and tell me what your expectations were for yourself as chief justice. How did you envision leading the court?

Wallace Jefferson: So many thoughts flooded through my mind. I became only the twenty-sixth chief justice in Texas, so you’re joining a small group of judges at the highest level in Texas. When I was president of the San Antonio Bar Association from 1998 to 1999, I had three primary goals. One was to increase access to justice for poor people in Bexar County, and so we tried to find a way to increase pro bono representation and coordinate law firms’ work on cases involving indigent persons. The second was using technology to help make the practice of law more efficient. And the third was looking at our history, preserving the work of lawyers and judges who had done amazing things over the years. So each one of those was going through my mind. The number one was helping poor people vindicate their rights in court. We established an Access to Justice Commission in April 2001 after I joined the Supreme Court, and we needed to expand on their work. But the real problem was that, beginning in 2004 or 2005, the money available for the program was plummeting. So we had to find additional funding, and I wanted to get lawyers and the court united behind it. The second was bringing the courts into the electronic age. Our proceedings at the Supreme Court were not broadcast over the Internet, so I urged my colleagues to go forward with putting cameras in the courtroom; now the public is able to witness the great legal issues of the day. And it provided a forum for civics education. Here was my big frustration on the court, even prior to becoming chief justice: most of the reports about our work boiled down to who won and who lost. So maybe the public is mad that Smith won and Jones lost because Smith is a bad guy, but there was very little analysis of why Smith won. And so the public would get mad at the court even though we were enforcing a statute that the Legislature had passed and the governor had signed. I wanted the public to be able to dig down a little bit, so when you have cameras in the courtroom, anyone can watch the arguments and watch the court grapple with complex issues. Even though we are all Republicans—that’s often the label used in news stories about the court—we often have deep differences of opinion about the outcome of a case. And third, I wanted people to have an opportunity to access historic court documents, pleadings that went back to the founding of the Republic or documents that had Sam Houston’s or LBJ’s signature on them. You could go back and look at records pertaining to slaves; you could review the disputes that occurred during the oil boom. The problem is that most state and county courts don’t have archivists, and they don’t know how to store those documents. So we established a task force in 2007 to study how to preserve historic legal documents, digitize them, and make them available to researchers and the public.

BDS: Despite your efforts to make the Supreme Court more transparent, do you worry that the average Texan doesn’t understand how the court affects his life?

WJ: We hear cases that involve millions of dollars, and they really do impact the public’s daily life. Think about a thing like eminent domain. What’s the scope of that? How far can the state go? What are the constitutional limitations? Or think about water rights and what that means to the future of the state of Texas. Do you own the water under your land? Can it be regulated by water districts? But the public doesn’t really pay attention to those issues, in my estimation. The case that I think got the most attention during my tenure was whether pet owners could recover mental anguish damages for the negligent or wrongful death of their animal. [Editors’ note: In April the court ruled against a bereaved dog owner in Strickland v. Medlen.] The reaction was furious—not furious in terms of being mad at the court but in terms of the activity in the newspapers and blogs and on TV. We got calls from other countries. When the public sees an issue that hits close to home and makes headlines, that’s when they become engaged and understand that there is a high court that has this responsibility of declaring what the law is.

But in general, many of the people that I talk to during campaigns who are not lawyers are unaware that they even elect judges. They go into the ballot booth and vote a straight ticket—either Republican or Democrat—and they don’t understand the impact all the way down the ballot. And I think that’s unfortunate and leads to irrational voting. People are perhaps voting in judges who don’t have the qualifications to serve. In 2008 Barack Obama won Harris County, and so just about every Democratic candidate for judge in the county defeated a Republican incumbent. It’s not because the Republican incumbent was lazy or inefficient, but only because that incumbent was in the wrong political party during that cycle. And that same election, every statewide office was won by a Republican because the state, as a whole, voted for John McCain. So they voted for me by wide margins, but not because they knew who I was. It was my party affiliation. The second-biggest factor is the sound of your name. “Wallace Jefferson” is a good ballot name. It sounds strong, and I thank my parents for that. But again, that says nothing about my competence. I think the third most important factor is how much money you were able to raise and spend on advertising. But in those advertisements, all you’re trying to do is give the voter a pretty general impression. It’s very hard for a voter to look at the breadth of your conduct in office.

BDS: So I could run and say I’m a conservative who will strictly interpret the law. That would probably win me some votes.

WJ: It would. And that’s about all you need to say. You have these buzzwords that don’t really mean very much, and it becomes marketing. So, if you’re in the right party, and if you have a good name, and if you have enough money to create a good marketing scheme, then you’re much more likely to win. But again, those three things don’t really tell the voter, Is this judge intelligent? Does he work hard? Is he fair? Does he conduct his court proceedings with dignity? That’s the biggest flaw in our system of electing judges right now.

BDS: It’s no secret to anyone who has followed your career that you would like the system to change. But what is a better way? If you could wave a magic wand, how would you fix the process?

WJ: I would listen to former U.S. Supreme Court justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

BDS: Who was born in El Paso.

WJ: Yes, but when she was Senate majority leader in the Arizona legislature, she helped create a commission that is chaired by the chief justice of that state with appointees from the speaker and the lieutenant governor and the governor. If you want to be a judge in Arizona, you submit your name and application to this commission, and the members have objective factors to consider: How many trials has the judge had? How many arguments has he had in appellate cases? What do his peers think of him? The commission comes up with a list of recommendations that they send to the governor. And then when a judge is selected by the governor, he or she serves for a term and is evaluated by a judicial commission, which will recommend whether that judge be retained. It then publicizes this recommendation, and the judge is subject to a public up-or-down vote. This is nonpartisan, so typically there is no need for the judge to raise very much money, and the voter comes into the ballot booth knowing there has been an open process that has determined that this judge is qualified for office. But if the public thinks the judge has not done well, there’s a chance for the public to hold the judge accountable. I think that’s about the best you can do.

BDS: Will we ever see anything like that in Texas?

WJ: I think it’s a tough argument to make. Number one, it’s hard to make any change in the Legislature. The status quo is a very forceful, potent weapon against any sort of evolution like we’re talking about. Number two, there is an investment by people who run campaigns to retain the current system. It generates a lot of money. And number three, the parties are reluctant to change. You know, Harris County, Dallas County, and now Bexar County have become more strongly Democratic, and they would say, “Why would we want to change now that we’re winning?” The Republicans would say, “We’ve been the kings of state government since 2002, so why would we want to risk losing that dominance?” But, you know, every session there’s a new Legislature, and you just have to make the case again.

BDS: You’ve mentioned the Legislature a couple of times during our conversation. I’d like to ask you about your State of the Judiciary speech from last session. Here’s a passage from your remarks: “We must ask instead whether our system of justice is working for the people that it has promised to serve. Do we have liberty and justice for all? Or have we come to accept liberty and justice only for some?” Do we have liberty and justice for all?

WJ: No. We’ve got a long way to go. The one thing I realized in pursuing access to justice for the indigent is that it’s a much larger problem than that. The poor people, yes, are turned away. They can’t afford a lawyer, so their rights go unprotected in far too many cases. But the middle class doesn’t have access to justice because it costs too much to hire a lawyer. So if you are in an abusive marriage but you don’t have the money to hire a lawyer and you’re turned away from a legal aid organization, you suffer. And we haven’t done enough in Texas to make sure even the unrepresented—those who can’t find a lawyer for free or hire a lawyer—have a chance to get to court and plead their case. And so we’ve been working on things like forms for that very instance, so you can get a temporary restraining order online and go to a judge and say, “Here’s what’s going on. Can I get some relief?” Last year the court adopted forms for divorces, so that people who can’t afford a lawyer but need to find a way out of an abusive or loveless marriage can potentially represent themselves. There are counties around the state that have developed self-help centers in courthouses, so somebody can walk you through how to file a case involving a dispute between homeowners about their fence line or what have you. I think we have to do more of that. If you’re a small business owner and somebody has cheated you out of a fee that you’ve earned and the amount in controversy is $5,000, you go to a lawyer and a lawyer says, “I need $20,000 just to take the case.” So they give up. I don’t think that’s right. We’ve got to be a better state than that.

BDS: Looking back on your tenure, are there any cases that you reflect on and say, “I might have come at that a different way”? Or is there a decision perhaps that you regret?

WJ: [Long pause.] I don’t think so. On each of the cases that produced an opinion, there was a lot of discussion in the court. We got to a point where the arguments were laid out, the counterarguments were clear, and you worked to reach the result that you thought was fair. So none come to mind. That’s not to say that if somebody brought me a case and said, “Was this really right?” I might reconsider.

BDS: Let me flip it—is there a ruling you are proud of that will stand as an example of the legacy of the Jefferson court?

WJ: I’m uncomfortable answering that. I don’t know. I mean, I think we’ll see in time. What I was trying to do with every case was study that case as closely as I possibly could. I wanted to write an opinion that would clarify the law, not just for the litigants in that case but for judges throughout the state and for the public to understand why we reached that result. So if there’s anything I’m proud of, it’s that I think not just me but my staff attorney Rachel Ekery, the many law clerks that served for me, and the other judges and their staff attorneys and law clerks studied these issues seriously and grappled with them at a high level of sophistication. During my twelve years I’m proud to have witnessed that.

BDS: So tell me about your decision to step down from the court, which you announced in September. Why was it time to leave?

WJ: I thought that the court had accomplished a lot during my term. And I would have been on the ballot in 2014. As you know, I’m not a fan of electing judges, and the thought of going through that process again, raising money, and potentially having an opponent in either the Republican primary or the general election or both was daunting to me. I’d already done three elections, so I knew what was on the horizon and was reluctant to go through that again, especially if we didn’t receive a level of pay that I think judges ought to receive. I always want to make clear I’m not complaining about salaries as a personal matter, but I think we need to be able to retain judges who are willing to sacrifice for the privilege of being a public servant who can easily be far more successful in the private practice. And I don’t think we were there. It had been eight years since the last judicial compensation adjustment, and that was about half of what the Senate had recommended. I didn’t think my family would be able to continue to make it for a full term, for another six years, and so all those factors came into play. I’ve got a kid in college, another one who’s a senior in high school who will be in college, and I think it just comes to a point in life when the question is, “Could you do better for your family by making this move or not?”

BDS: A lot of people reading this interview might say, “He’s making more than $150,000 a year. I’d love to have that salary to put my kids through college.” Is that a fair argument?

WJ: I’ve heard that a lot, but I would turn it around and ask that person, “If you had the option of doing far better financially for you and your family, would you take that option?” It’s an individual decision. I left private practice to join the Supreme Court, and the compensation levels in private practice were far higher than they were at the state. But I thought I could make a contribution because I’m not motivated simply by money. And there are so many judges across the state who are brilliant and could be the general counsel for major corporations and be making millions. Instead they say, “No, I want to see if I can improve people’s lives through my service.” You want people to serve who could do far better in the private sector but are willing to forgo that to give back to the citizens.

BDS: There’s a brain drain in the legal profession because of that. Judges can begin to receive a pension after twelve years or so and can then go to the private sector and make a lot of money on top of that.

WJ: Let’s say you’re in private practice, and you’re doing very well. You get important cases, and somebody asks you, “Would you be a judge?” Well, you’re thinking not only of the compensation. You’re thinking, “Do I give up this thriving practice to be a judge in which I’d have to run a campaign right away even though the politics can be very ugly at times?” And I can’t say that I will win or not win based on my qualifications. It’s going to be based on factors that I have no control over, which we’ve already discussed. And so I would love public service, but do I give up everything that I have now only to be defeated in the next election?

BDS: You sound like a man who has run his final campaign.

WJ: I don’t see myself running for public office anytime in the near and probably distant future, but I want to remain active in matters that impact public policy as a private citizen. You hear a lot of criticism of public servants—people in the Legislature or in the executive branch—and I understand the nature of that criticism, but I think if people really saw how the staffs of these representatives and senators devote themselves to trying to get policy right, if they saw some of the debates, they would come away impressed. I don’t think that story is told that often.

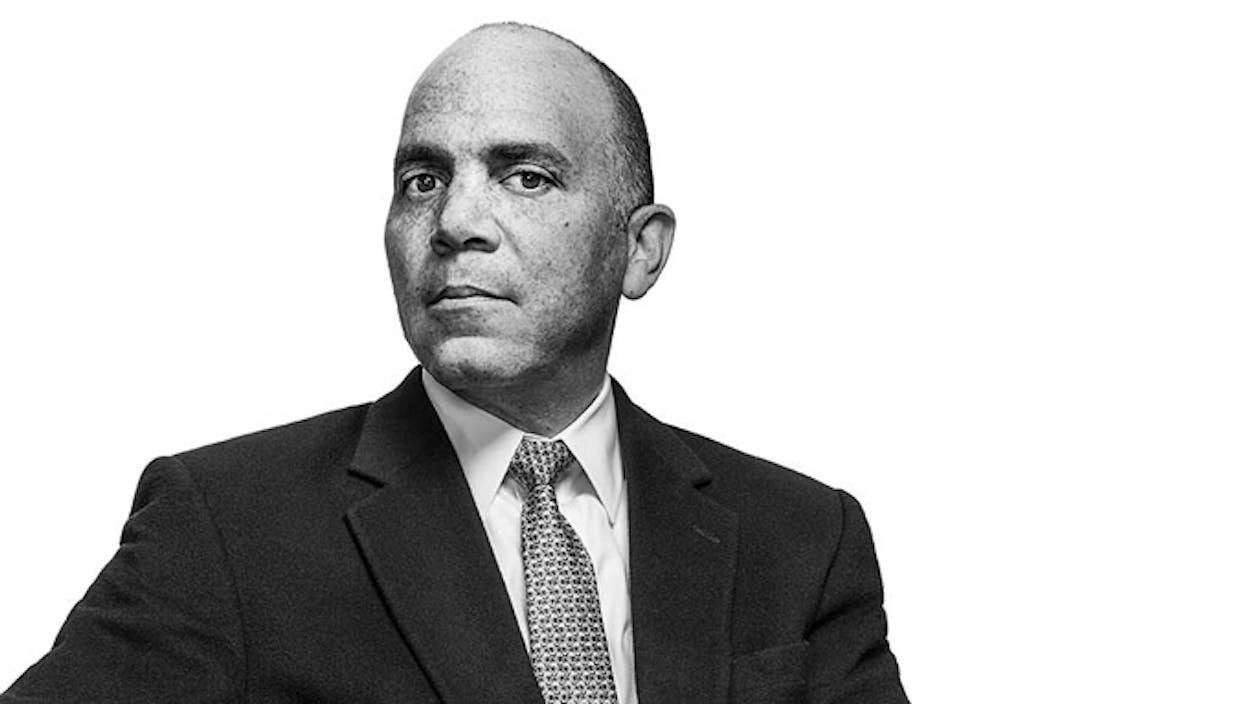

BDS: I’m sure you weren’t surprised to see that most of the press clippings about your announcement mentioned in the first line that you are the first African American appointed to the Supreme Court and also the first African American chief justice. How important is that to you? Or is that a label of little consequence?

WJ: The answer to that is complex. But I think back to my parents and our family history in Texas. Let me just start with my father, who was born in Chicago and grew up in Milwaukee, which is where he met my mother. In 1952, after a year at the University of Wisconsin—he played football—he enlisted in the Air Force. He would tell a story about going down for basic training at Lackland Air Force Base, in San Antonio, and he rode down on a bus. There were many places where he was refused a room because of the color of his skin. And the farther south he went, the more he saw segregated water fountains and theaters and restaurants. He told that story with disappointment in his voice, not anger. It was hard for him to understand how that could happen. But then he went to basic training and, through the military, got his undergraduate degree, and later he got his master’s degree in political science. He went to Officer Candidate School, and he became an officer. One of my first images of my dad is going to church on Sunday morning on the military base. The soldier guarding the gate would look at the bumper and see that an officer was coming, and that soldier, whether it was male or female, black or white or Hispanic, would stand at attention and give my father a sharp salute. All that is to say, we have a very complicated history in the United States where it used to be you couldn’t achieve great things because of the color of your skin, or because of your gender, or because of a physical disability, but there are ways to overcome those. I think what my father demonstrated was that you could achieve your goals if you were willing to put in the work.

So when I was appointed chief justice I thought it was a good example of that. If you become educated and do the right things and stay out of trouble, there is at least the opportunity for you to achieve high office or to be successful in business. But then, after the announcement that I would be the chief justice—it happened that I was on the front page of the San Antonio Express-News and on television—I went to a Spurs game, and people recognized me. And these African American grandmothers and grandfathers would come up with their grandsons and granddaughters and say to them, “I want to make sure you meet this person, because he’s the first African American to become chief justice, and what a great achievement that is.” Now, these grandparents remembered the days of segregation, and they wanted to show their family members that there don’t have to be barriers to achievement.

I want to make sure that I don’t let them down. And how do you do that? It’s not by concentrating on race but by doing what my father did. You put your head down and try to do a really sound job with everything that you do. Make sure you hold the office with dignity. Demand it of others, and more little kids might just think, “I’ve got a chance to succeed.” And all that’s wrapped up in this historical situation about my family. My father was born in Chicago, but his mother was born in Palestine. After Alex Haley’s Roots became a miniseries, my father and I decided to see if we could find out more about her family in Texas, and we discovered that her great-great-grandfather Shedrick Willis, who lived in Waco, was a slave, and his owner had been a state judge. Remarkably, after the Civil War, Willis became a city councilman. And now that former slave’s great-great-great-grandson was able to become chief justice. This is, to me, a bigger story about America. We’ve come a long way in a short period of time, from slavery, where somebody could be bought and sold, to his descendant leading the state’s judiciary. I think it’s not only a story about race in America, but it’s an important story about the evolution of liberty in our state and our nation.

BDS: You are now starting a new phase of your career, returning to private practice at an appellate boutique law firm where your name will appear on the door: Alexander, Dubose, Jefferson, and Townsend. What will be your role there?

WJ: It’s a great firm, and the lawyers have extensive experience handling very contentious, challenging cases in state and federal appellate court. An appellate firm marshals arguments that can be presented to an appellate court, and the result is that those arguments establish a precedent that governs not just the parties that are before the court, but potentially statewide, or nationwide, if you’re at the U.S. Supreme Court. And so, in a way it’s doing the same thing I was doing on the Supreme Court, and that is trying to find the accurate legal position in a case. And the good thing about this firm is that it does that at very high levels, but also gives back. They are a part of appellate pro bono cases, so they will represent people for free in cases in state and federal court. So it wasn’t just driven by clients who have a big wallet, but also by concern for our fellow Texans.

BDS: Are you going to miss wearing robes to work?

WJ: You know, you only wear a robe when you’re in court. Most people think of judges on the bench all the time, but it’s really only about six hours a month plus official ceremonies. But I will miss the role, and all of the policy issues that I dealt with.

BDS: Are there cases you will recuse yourself from because of your work on the Supreme Court?

WJ: My position, and I discussed this with the firm before I came, is that if a client comes to the law firm about a case that was at the Supreme Court of Texas while I was a judge, I want nothing to do with that case. There are ways for them to ensure that I am walled off from that case if the client is insistent on hiring the firm, but I won’t touch it. And I think it’s the clearest thing I can do, to ensure that there’s no question that I would use some confidential information that occurred when I was a justice on the court for a private purpose.

BDS: When you size up the trends of the major law firms in the state, is it a good time to be a lawyer?

WJ: I think it depends on what level of a lawyer you are. It’s been very difficult for young lawyers to find work, generally, and as a result the law school classes are down, fewer people are applying to law school, because they don’t think it provides the immediate entry into, you know, a good profession. And even those that find jobs, many of them are working not in the court room but doing discovery, and much of it is electronic discovery, which for some is not the most fulfilling kind of practice to have. But I think there’s an opportunity here, to match these new law graduates who can’t find jobs at the big firms with the desperate need we have for the middle class and the poor for representation. So maybe they won’t be making the $170,000 that you make at the most profitable firms, but they can make a good living, and their hourly fee can be greatly reduced, and maybe now that small business owner with a $5,000 dispute can find a lawyer to help represent them. I think that’s where we need to go, and it’s possible that we can find that match. We just have to think creatively.

BDS: Does that mean it’s a bad time to be a law student?

WJ: I think law students need to think about what they want to do with their professional lives. It’s not going to be automatic that you graduate from a law school and you go to work for one of the top law firms in the state or the country. So if it’s not automatic, what else are you willing to do? And I believe that most graduates of law school, what they want to do is get in court and represent somebody and help them where otherwise they would have their rights go unvindicated. So they have to figure that out. There are fewer cases going to trial, and there are more going to private arbitration, so the nature of the legal profession is changing. They need to study that, look at trends and decide what they want to do and which law school can take them there.

BDS: Is Justice Don Willett the same in person as he is on Twitter? And has he offered to give you any social-media lessons?

WJ: He is, I would say, one of the most famous members of the court. I don’t follow him on Twitter, so I don’t know if he’s the same in person, and he has not given any tutorials. I signed up a few years ago when I was thinking I’d have to campaign, but I never used it. The danger is, how far do you go? I don’t have to worry about that now.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy