Mass shootings barely register now unless they provide some new twist or new level of horror: six-year-old victims, Sandy Hook; 422 people shot, Las Vegas; racial terrorism, El Paso. When a colleague googled “mobile mass shooting” to see if there was any kind of precedent for the event that took place in Midland–Odessa on Saturday, he discovered that nine people had been shot in Mobile, Alabama, on Friday, an event I had not heard of otherwise before or since. Searching for “Alabama shooting” just now, I found out that a fourteen-year-old in Athens, Alabama, killed his five family members Monday night with a 9mm pistol.

At seven deaths and 22 injured, including a seventeen-month-old toddler, the Midland–Odessa shooting doesn’t rank particularly high on the grim scoreboard we’ve erected for these things. But it is different in a couple ways. First, there was the way the shooter careened across the two cities, causing random mayhem instead of focusing fire on a specific place or population. Second, the shooting followed another terrible gun attack less than a month earlier in El Paso, which spawned weeks of pointless meetings convened by Governor Greg Abbott and silly arguments about gun violence in Texas. At the moment, the Midland–Odessa shooting seems notable partly for demonstrating once again the extraordinarily poor quality of the explanations we’re getting from many Texas leaders about what’s going on, and why.

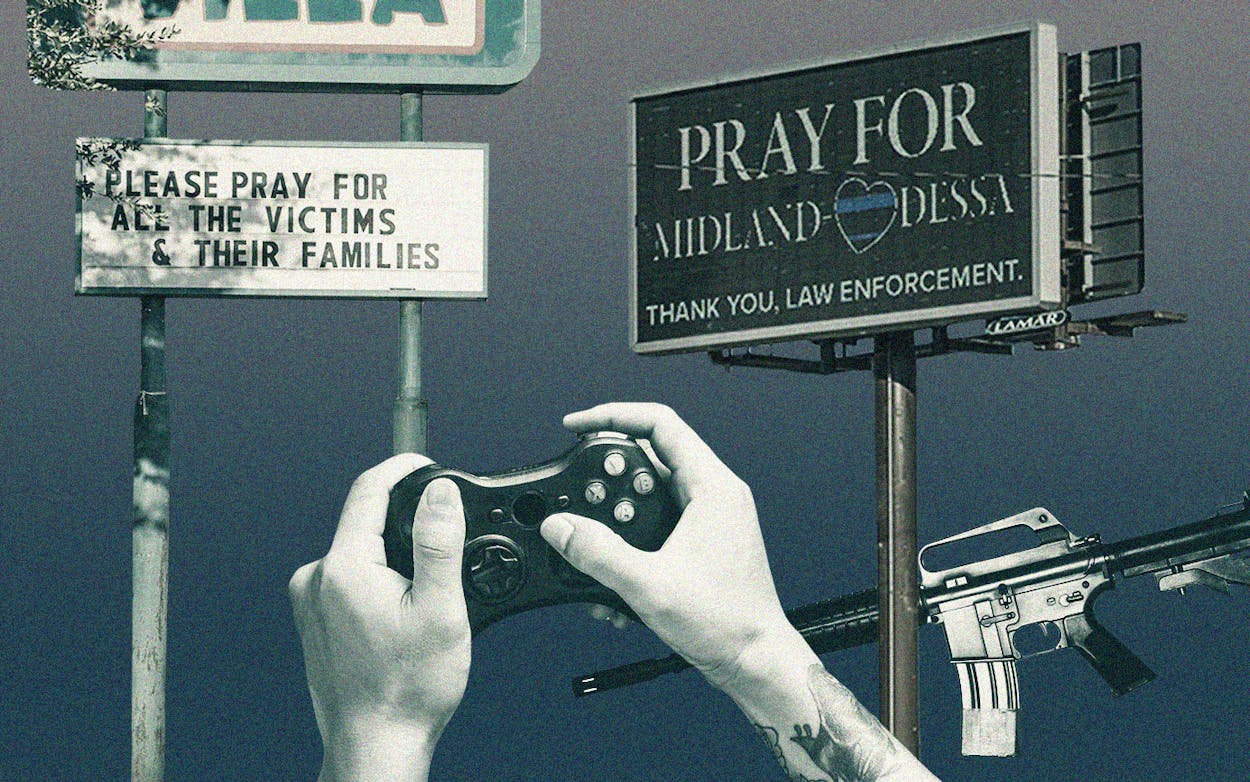

Odessa mayor David Turner blamed video games, just as President Donald Trump and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick did for the domestic terror attack in El Paso. The alleged gunman in Midland–Odessa was a 36-year-old unemployed truck driver whose home apparently lacked electricity, so he seems unlikely to be a Fortnite fanatic. Abbott tweeted that the shooter had a criminal record and that “we must keep guns out of criminals’ hands,” which is true and more helpful, but also an example of cramped thinking: presumably the goal is to prevent anyone from carrying out a mass shooting, not just those who already have criminal records.

In the past, Republicans and gun-rights activists typically responded to mass shootings by arguing that the state should make guns more available for self-defense. That’s the logic behind the raft of new gun laws that went into effect on September 1, just hours after the shooting. But can you think of a place where you’re more likely to run into people with guns than Odessa? The uselessness of a handgun in a hip holster is made clear by the image of the alleged shooter zooming down a highway with an AR-15.

Perhaps most notably, before the victims had even been identified in Odessa, state representative Matt Schaefer stepped in with a thread on Twitter that quickly went viral. “I am NOT going to use the evil acts of a handful of people to diminish the God-given rights of my fellow Texans. Period. None of these so-called gun-control solutions will work to stop a person with evil intent,” he said. “What can we do? YES to praying for victims. YES to praying for protection. YES to praying that God would transform the hearts of people with evil intent. YES to fathers not leaving their wives and children. YES to discipline in the homes.”

There was one public policy problem at the heart of the mass shooting epidemic, Schaefer said. “Godless, depraved hearts. That IS the root of the problem. Every person needs a heart transformed by faith in God through Jesus.” That’s a sentiment Schaefer’s Jewish constituents no doubt appreciate, and it’s worth noting that “pray to end it, because laws can’t” is emphatically not how Schaefer feels about abortion. Schaefer’s remarks were clarifying. They make sense, as do other remarks made by public officials after the shooting, only in the context in which guns are the totems of their own kind of religious belief, items that cannot fail but can only be failed, whose worth is inherent and not subject to empirical study or the vagaries of public policy.

He’s not alone in that.

A long time ago, my dad was an FBI agent. On the few occasions he found himself in an environment that felt dangerous, he was struck, he told me, by the tremendous psychological benefit of carrying a gun. It wasn’t just the superficial awareness that he could use lethal force if required. It was a kind of gauzier feeling of invulnerability, as if he were the only person in each room he entered who had real agency. But he was also smart enough to know, he said, that the feeling was a mirage, and that it was even a dangerous one, a kind of drunkenness. If the confidence it gave him led him into a bad situation, one in which the revolver wasn’t useful, the gun had hurt him, not helped.

The .38 Special he carried looks like a child’s toy compared to the weapons used in most recent mass shootings, including the AR-15 in Odessa. But we seem to be suffering, collectively, from a version of that haze. Fewer than a third of Americans own guns. Many in that group have a more traditional, utilitarian, healthy relationship with firearms, but some portion of them feel that sense of agency very strongly. The free availability of firearms is key to their sense of being a person with power in the world.

That sense of power is impervious to the empirical studies that have demonstrated, over and over again, that when you have a gun in your home, you’re much more likely to have it used against you, use it to kill yourself, or shoot an innocent person intentionally or by accident than to successfully use it in self-defense. You’re also much more likely to have a home invader shoot you. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that living in a home where guns are kept increased an individual’s risk of death by homicide between 40 and 170 percent, and one published in the American Journal of Public Health found that individuals who owned guns were about 4.5 times more likely to be shot than those who didn’t. But you’ll never convince a single person for whom gun ownership is important with figures like that, because the feeling of gun ownership is so powerful.

In 2017, a pair of sociologists at Baylor University looked at the data and found that “simply owning a gun does not predict an individual will express anti-gun control opinions, but rather whether the person feels empowered by the gun.” The extent to which a person feels “empowered” by gun ownership basically comes down to how alienated that person is from the wider culture. If the person is experiencing economic stress, they’re more likely to find guns “morally and emotionally restorative.” If they exhibit meaningful social connections, like regular church attendance, they’re less likely to see firearms as giving them a sense of purpose. The most intense form of gun ownership was a kind of salve, the researchers found, which gave meaning to people, predominantly white men, who were otherwise experiencing a loss of status.

The public debate we’re having is really about how much that special sense of power should be protected, and at what cost. When people blame video games, or godless hearts, what they’re saying is that it should be protected at any cost, and that no number of seventeen-month-old shooting victims is worth the discomfort of a fairly small number of super-active gun owners. When leaders like the governor convene a series of closed-door “commissions” to mute the conversation, what they’re doing is abetting that sentiment, because the votes of that small number of people are important to the Republican coalition.

It’s a perverse state of affairs, and Schaefer’s tweets were profane. We may not be any closer to changing the politics of guns in this country. But we’re seeing more clearly what’s going on, and who it benefits. That’s a start.

This article has been updated to correct the misidentification of Odessa mayor David Turner as David Brown.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Crime

- Greg Abbott