At 1:45 p.m. on Friday, July 18, White House communications director Dan Bartlett strode into the James S. Brady Briefing Room to confront a large, hostile, and deeply skeptical group of reporters. The issue in play was an erroneous assertion by George W. Bush in his January 28, 2003, State of the Union address: “The British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.” While that statement was true in the narrowest sense— the British had indeed reported it—the U.S. intelligence community had serious doubts; a similar line had been cut from an earlier presidential speech. But Bush had uttered those sixteen words anyway, and then the White House had compounded the problem by blaming the Central Intelligence Agency, a spectacular tactical mistake that triggered an ugly political catfight. This was serious stuff: The president’s honesty was being called into question. The press, which already suspected that the government’s intelligence on weapons of mass destruction had been sexed up to serve Bush’s political agenda, had gone into overdrive. Bartlett, an affable 32-year-old Texan with all-American good looks, was there to take his best shot at cleaning up the mess.

The orgy of finger-pointing and recrimination was definitely not business as usual. Like his former boss and mentor, Karen Hughes, Bartlett ran a tight ship. The 52-person communications shop he controlled was famous for its lockdown discipline and airtight message control. Reporters often complained about how stingy it was with information and how stubbornly it clung to the designated message du jour. Now all hell was breaking loose. While tape recorders clicked on in the Brady Briefing Room, Bartlett—speaking on background, as he often does, as a “senior administration official”—launched into a marathon defense of the war. He not only had to deflect criticism of the bogus uranium story; he had to rebut the larger implication that the entire justification for the war was tainted.

To help make his case, he had persuaded the intelligence agencies to declassify portions of a National Intelligence Estimate, which included their principal summary of Iraq’s weapons programs. Bartlett showed reporters the parts where the agencies had overwhelmingly agreed that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. He showed them where it said that Iraq was trying to buy uranium in Africa, and he showed them the State Department’s claim that those reports were “highly dubious.” The thrust of the briefing was: Look, we didn’t make this stuff up; we got it from our intelligence agencies, and yes, there was some doubt about the uranium deal, but it wasn’t conclusive. After an hour of questions, Bartlett believed he had done as much as he could to reassure the press of the White House’s sanctity of purpose. “When I gave the briefing,” he said, “I thought I was giving them everything we knew.”

To his chagrin, the administration had made yet another set of assertions that turned out to be wrong. Four days later he was back in a briefing room—this time the Roosevelt Room, which holds far more reporters, and this time on the record—to earnestly explain why the sixteen words were mainly the White House’s fault after all. Over the weekend White House officials had discovered that George Tenet, the director of the CIA, had told them himself that the uranium story was bogus not once but three times.

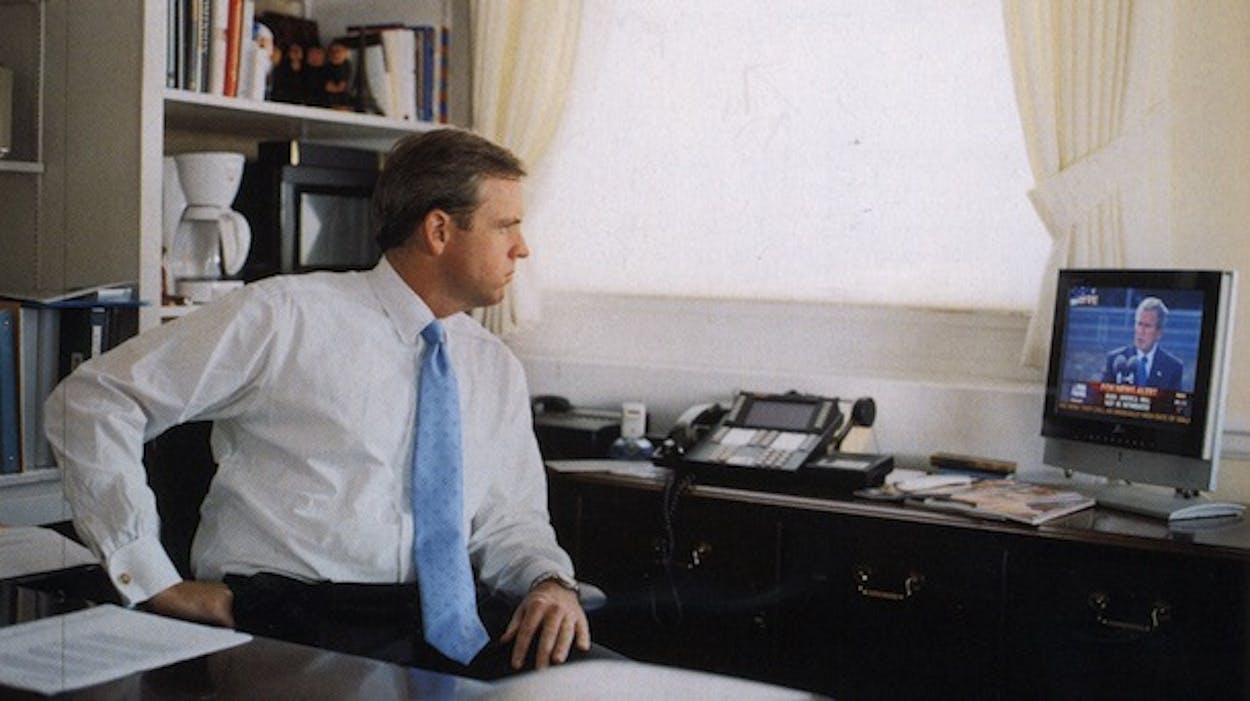

“It was like being punched in the gut,” Bartlett told me when I interviewed him in his West Wing office in August, describing the feeling of being at the center of the media storm. “Every time we thought we had it under control, something else popped up. There was never an intention to shift the blame onto the CIA. But that was clearly how the rank and file perceived it.” Bartlett also insisted that part of the problem was timing: When the news broke—triggered by then-White House press secretary Ari Fleischer’s concession that the sixteen words should not have been in the speech—Bush, Bartlett, and national security adviser Condoleezza Rice happened to be in South Africa, and Tenet was on the West Coast. Bartlett was thus unable to follow the first rule of damage control: Put all the players together in the same room and plan strategy.

“There is a sense,” he said with a sigh, “as the frenzy comes upon you, almost of resignation. You know it is going to run its cycle. The question is, how long?”

Considering what Bartlett does for a living, which is to get the spit knocked out of him with alarming regularity by the velociraptors of the media, he seems altogether too nice. You might expect instead someone far more layered, riven, scarred. You might expect someone with a world-weary and perhaps faintly self-indulgent sense of the great burden he bears. You would not be quite ready for this pleasant escapee from a Norman Rockwell painting, this self-possessed former chapter president of the Future Farmers of America who says he has never harbored any strong ambition to be, or to do, anything in particular. Sitting in the quiet, sunny office he inherited from Hughes, it is hard to imagine that he spends a good deal of his eighty-hour-plus weeks engaging in “crisis communications,” a White House euphemism for “what you do when you’ve got a thousand reporters breathing down your neck.” And yet, by virtue of several large accidents of fate, a sui generis relationship with Bush, a taste for combat, a rare ability to schmooze reporters without compromising his boss, and a talent for putting out political fires, this hyperbaric corner of the West Wing is emphatically his domain.

Aside from his youthfulness, his wholesomeness, and the question of what such an even-keeled guy is doing in this graveyard of the well-intentioned, the reason to be interested in Bartlett is that he is the linchpin of the most far-reaching, tough-minded, and technologically advanced government communications operation in history—one whose sophistication, sweep, and scope make even the silken spinners of the Reagan era seem primitive by comparison. While Reagan’s team pioneered the staging of news, they really had to worry only about getting one shot and one soundbite for the evening news. Bartlett lives in, and grew up in, an all-news-all-the-time world crammed full of yammering talk-show hosts and instantaneous headlines, one in which every presidency is by definition a media presidency. His purview, therefore, extends to the full global warp of the 24-hour news cycle, where the words uttered by a White House spokesman at a morning briefing show up on CNN in Stuttgart that afternoon, in Internet chat rooms in Moscow by early evening, and cause Tokyo’s Nikkei stock index to plummet the next morning.

During the Iraq war, Bartlett oversaw an hour-by-hour flooding of the worldwide airwaves with the Bush message, carefully synchronizing the efforts of the State Department, the Defense Department, and the Justice Department (all of which, not coincidentally, had public-information officers handpicked by the White House; so did military headquarters). From the early-morning informal press briefings for the benefit of the morning news shows to the midday press conferences at United States Central Command in Qatar to the formal late-afternoon Pentagon and White House briefings to the steady stream of talking heads on TV and in print, nothing like this had ever been tried before. “Such a comprehensive communications strategy for a war,” wrote Washington Post reporter Karen DeYoung, “is unprecedented in the modern White House.”

When things go right in Bartlett’s White House Communications Office, as they did in May, with the president’s speech and photo op from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln proclaiming the end of major hostilities in Iraq—largely conceived, designed, and executed by Bartlett’s minions—or in the stunning secrecy with which Bartlett and a handful of other colleagues plotted the roll-out of the Department of Homeland Security, he basks in the warm afterglow of a gigantic PR victory and in the knowledge that thousands of angry, envious Democrats are muttering imprecations against him. When things go wrong, that glow is a harsh, unflattering spotlight. When the president wants to know why the press is hanging him out to dry over his private stock deals, as it did in 2002, Bartlett is the rapid-response guy. When Al-Jazeera sets the newswires ablaze, as it often does with information the Bush administration deems false or biased, he is the fireman. The press secretary is tactical, existing solely in the daily spin cycle. Bartlett, the communications director, lives three to six weeks in the future. His focus is on the Big Picture, on planning the overall strategy of which press conferences are only a part. When Bush’s popularity ratings decline—as they have in recent months—then one has to wonder if it’s due to the message or the message machine. In any case, it’s Dan Bartlett’s problem.

If the Bush Administration has a true wunderkind, whiz kid, or whatever you call a young person who manages to dazzle his older colleagues with abilities that seem well beyond his years, that person is, unambiguously, Daniel J. Bartlett. He is among the youngest people in the history of the White House to have Oval Office walk-in privileges. Though he denies any such ambition, many of his friends in the Bush administration have predicted he’ll one day run for office. (The Washington Post speculated that he might run for Texas governor, for which, he says, he caught no end of teasing.) He has a relationship with Bush that has conspicuous father-son overtones. The age difference is right: 25 years. Bush has no son. Bartlett’s father moved out when he was a child, and by his own description, Bartlett spent his formative years seeking out the company of older, self-sufficient, professionally competent role models.

This is not to say that Bush is soft on Bartlett. On the contrary, by all accounts, Bush is a taskmaster, a bottom-line, goal-driven guy who wants answers in meetings with no fuss or chatter. “He’s fast and hard and direct, and he doesn’t pull any punches,” says veteran political operative Mary Matalin, who resigned last year as counselor to Vice President Dick Cheney. In his book Bush at War, Bob Woodward writes that when Bartlett went to Bush to suggest new wording for his post-9/11 television speech, Bush barked, “What? No more changes!” Bush was also sharply critical of Bartlett for not making bigger news out of the president’s decision to freeze the assets of terrorists. According to Bartlett, “He was very tough on me early and at different junctures in my career when I took on more responsibility.” But Matalin says that Bartlett responded well. “He’s so methodical and unflappable,” she says. “He’s complementary to the president.”

Bartlett has actually been the Bushies’ version of a wunderkind for a long time. It is only now, in the nearly sixteen months since he took over the reins of the communications office from Hughes, that the rest of the world has begun to pay attention. He was born in Waukegan, Illinois, and grew up in the North Texas town of Rockwall, about 25 miles northeast of Dallas. His parents divorced when he was in seventh grade, and his father left the area. He and his siblings—two brothers and a sister—were raised by their mother, who ran a school for gifted and talented minority children in the South Dallas neighborhood of Oak Cliff.

Rockwall, which has since become a bedroom community of Dallas, still had plenty of pigs, cows, chickens, and planted fields when Bartlett was growing up. “It was a city in transition,” he said. “There were people commuting to Dallas, but I was attracted to and got involved with people who were farmers and ranchers.” He took agricultural classes at school and became active in the Future Farmers of America. “The dirty secret of the ag classes was that they were not very rigorous,” he said. “If you were in advanced ag, your first period was basically going off campus to take care of your animals.” Bartlett purchased, raised, and sold three steers while he was in high school, ran a feedstore, and played varsity football and basketball at Rockwall High. He loved hunting, especially dove and quail hunting.

He attended the University of Texas at Austin, where, he said, “I was always good at doing enough to get by. I didn’t excel much in academics and didn’t become intellectually focused until late in college. I have always been the type who got on well with a lot of people and was kind of pleasant to be around.” He did manage to figure out that he was more politically conservative than many of his classmates. “In my political science classes, just outrageous conclusions were being drawn from current events as well as history,” he said. “They had a very pacifist view of foreign wars, and they were passionately against Reagan. It wasn’t even so much my peers as it was the faculty. I remember sitting there scratching my head and thinking, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.'” Bartlett and two friends who likewise spoke their minds became known in one class as Public Enemies One, Two, and Three.

While he was still in school studying political science, Bartlett began to dabble in politics. He went to work in the Texas Senate for his local state senator, Democrat Ted Lyon, and in 1992 took a job with a little-known political consultant named Karl Rove at Rove’s small direct-mail business in Austin. Bartlett had barely heard of Rove, but he immediately realized that this was no ordinary operative. “My first day on the job, thirty minutes after I got there, the guy next to me picked up the phone and said, ‘The president of the United States is on the phone for Karl.’ All of a sudden I was very interested in knowing who this guy was.” In 1993, working for Rove and still taking courses at UT, Bartlett signed on to the fledgling campaign of an untested gubernatorial candidate named George W. Bush. The campaign, which was run out of Rove’s office, had only two paid employees. Bartlett was 22.

He quickly made himself indispensable. “He came up on the Bush radar early,” says his boss at the time, Vance McMahan, Bush’s main policy guru. “The campaign was such a lean organization, and he had direct access to the candidate. It was apparent right away that he thrives on being at the center of the action. If the team is down by one point with three seconds to go, he wants the ball.”

Bartlett’s wish was fulfilled when, in September 1994, he was charged with managing the press event at which Bush, hunting doves, accidentally and illegally shot a protected bird called a killdeer. A gleeful Capitol press corps jumped all over the story, and Bartlett had his first taste of crisis communications. “I saw Karen Hughes’s talents for the first time,” he said. “She told Bush, ‘You need to personally get on the phone with reporters.'” Bush did and made light of what had happened. “He came up with some good quips. He said, ‘I’m glad I wasn’t deer hunting; I might have shot a cow.’ It was pivotal in East Texas—I mean, growing up there and knowing how people react to things. I think it humanized him.” Says Hughes: “I remember Governor Bush telling Dan to go find a justice of the peace and pay the fine [for killing the bird]. We left Dan to take care of that. There were a lot of times when we left Dan to take care of things.” After Bush’s victory, Bartlett was given what for a 24-year-old was a position of great responsibility in the governor’s office: deputy director of policy. “It was clear from the get-go that this was a person of enormous talent,” says Rove. “We identified him very early, and he was sort of fought over after that.”

Friends and colleagues say they noticed back then that Bush and Bartlett had a great deal in common. They were both sports nuts (“UT football-obsessed” is how one friend describes Bartlett); they both liked to hunt; they both played golf (and still do together). And people who know them well say that Bartlett’s personality is similar to Bush’s. “Of all the people in the presidential universe, he is the one most like the president in demeanor, character, and wit,” says Bush media adviser Mark McKinnon, a managing director at the Austin public relations consulting firm Public Strategies. “They both have a sort of towel-snapping, jock sense of humor.” Bush once bet Bartlett $100 that he could beat him in a ten-kilometer race. Bartlett trained hard, won, and collected the $100.

Then there was the nickname. “Around the office we called him the Vice, as in vice governor,” says McMahan. “It was a lighthearted acknowledgment that his style was very similar to the governor’s.” Indeed, they both fracture syntax. They use common expressions, such as “like I said.” They both mispronounce the word “nuclear” as “nu-kyuh-lar.” And they share a fondness, apparently, for Yule-related pranks. As a junior at Yale, Bush and some frat brothers were caught stealing a Christmas wreath from a hotel. As a freshman at UT, Bartlett and some frat brothers were caught trying to steal Christmas trees.

Former associates say that Bartlett came into his own during Bush’s 1998 reelection bid and 2000 presidential race, when he was made the keeper of the governor’s personal background files. This meant that, to prepare for the inevitable press scrutiny, Bartlett had to do his own investigative reporting into sensitive areas of Bush’s background: his National Guard service, his career in the oil patch and with the Texas Rangers, and his youthful high jinks. He met and talked to almost all of Bush’s family and old friends, and he eventually knew everything about him, including the highly secret details of his 1976 arrest for drunk driving.

That’s why it was Bartlett, principally, who drew the rapid-response duty when news of the DUI broke during the last week of the presidential campaign. “I could literally feel the blood draining from my head,” he says of the moment he learned that a reporter had gotten onto the story. “I said to myself, ‘No! This is not happening!’ I remember going into a room where [campaign chairman and now Commerce Secretary] Don Evans was talking to Karl. I closed the door and told them, and there was just silence. Then I called Karen and the governor, who were traveling. I had never seen Karen speechless before.” Bartlett got on the phone with the press; Hughes held a press conference.

By that point, he and Hughes had developed a close working relationship. “When Karen was on the road and he was in [Austin], it got hard to tell where one started and the other stopped,” says Rove. No one was surprised when, after the election, Hughes asked Bartlett to be her deputy. He had successfully incubated with both Rove and Hughes, which made him exceedingly rare among the Bush loyalists. In April 2003, when Hughes announced she would be quitting, he got her job.

The message machine Bartlett runs is basically a huge, multifaceted sales pitch delivered through the megaphone of the global electronic media and designed to advance the Bush agenda. He gets to the White House every day at 6:15 in the morning, where he reads a large stack of newspapers and magazines. He has a standing morning meeting with the president, Rove, Rice, and chief of staff Andrew Card to discuss the day’s events. During the day he talks not only to reporters but to top presidential advisers like Evans and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz. He is rarely home before eight-thirty in the evening. He often works weekends at his home in Chevy Chase, Maryland (he and his wife, Allyson, a Houstonian who works as a financial analyst, have no children), and he travels frequently with the president on Air Force One; he was flying with him, for instance, the entire day of September 11.

Bartlett’s office consists of five divisions: press, which holds daily briefings on and off camera; media affairs, which deals with out-of-town press; speechwriting (the president makes more than six hundred formal public appearances each year, and most require speeches); communications, which is mainly strategic planning; and global communications, which deals with media outside the country. The rhetoric those divisions manage is complex, nuanced, and entirely driven by Bush’s shifting attitudes, desires, and ambitions. Bartlett presides over it all with a management style that his former deputy Jim Wilkinson describes as “quiet but very thorough. I have never heard him yell.” Bartlett is also known for his laconic e-mails: “I have had a lot of e-mails from him with one word: ‘agree,’ or ‘disagree,'” says Wilkinson.

One of the best examples of Bartlett’s message-meistering—his refining of a broad set of ideas about how and what to communicate—is the administration’s push for a Cabinet-level Department of Homeland Security. Bush’s plan, which was announced in early June 2002, was shrouded in such secrecy that only a handful of Bush’s seniormost aides knew about it. To ensure maximum secrecy, which was necessary, Bartlett says, because early leaks would have spurred congressional committee chairs and other interested parties into self-preservation mode, they met in the Presidential Emergency Operations Center, the bomb-proof bunker underneath the White House to which Vice President Cheney was taken after the terrorist attacks on September 11. They gathered information but told no one what they were doing. By the time the plan was ready to be announced—for a giant new agency that would subsume the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the Department of Transportation and represented the most significant restructuring of the federal government since 1947—not even Cabinet secretaries had a clue.

In Washington such an information blackout was unheard of, even by the standards of an administration known for its secretive ways. “When you are trying to develop a policy that will partly or significantly affect twenty-two different agencies,” Bartlett said, “there are institutional forces that are going to rev into overdrive when they hear about it. Turf battles will take place. In that context it is hard to make the sort of dramatic changes the president was trying to make.” Congress would still have to vote, but at least the White House had a running start. The communications plan that Bartlett and his team sketched out involved a televised presidential address followed by other speeches around the country. “Our decision was that the president needed to talk to the public and dramatize this,” he said. “So a lot of our people would spend time working on what he was going to say in making the case. We had Cabinet secretaries go out; they create an echo chamber for what the president is saying. We reached out through our legislative affairs office to our natural allies in Congress, who would also provide an echo. We did columnist outreach and worked by phone with the media.”

By most accounts, Bartlett is accomplished at the latter task, which takes up 30 to 40 percent of his time on any given day. “What makes Dan Bartlett good is that he gets the game,” says Time White House correspondent John Dickerson. “For Karen, this wasn’t natural. Dan’s relationship with the press is much better. I call him to get the real take on what is going on, and he does it without giving away stuff that will hurt him or his boss.” Says Matalin, one of the smoothest operators in the world of media and politics: “Either you know how to do this or you don’t. Dan is a natural at it. The idea is to give you just enough of what you need to make a story out of it without compromising the president.” Bartlett can be tough, as he was when he shut off access to Talk magazine when it ran a fashion spread mocking Bush’s daughters, but mostly he tries to be accommodating. He might provide a reporter with details of a meeting inside the White House, for example, that will considerably spruce up a story and give it an insider feel, which is the sort of thing editors love, all without talking about works in progress that the administration is not ready to make public.

This message discipline contrasts, to say the least, with the anarchy of Bill Clinton’s fantastically porous White House, which leaked merrily from every porthole and scupper. The change has been jarring for the reporters have who covered both administrations; nearly everyone in this White House has been unwilling to play the game even a bit. When Fleischer was press secretary, he was stubbornly on-message in briefings and stubbornly on-message if you called him at nine o’clock at night. If you were a reporter and wanted to have a long, informative, off-the-record chat with a Bush administration official, then your only real options were Bartlett or Matalin—and, of course, she’s no longer there. Hughes says that part of the reason for withholding information from reporters is that to do otherwise would be to play favorites: “We don’t think it’s fair to pick and choose your favorite reporter and pick and choose who to tell things to first. I don’t think it’s fair to pit reporters against each other.” Of course there are exceptions to this. In July two senior administration officials divulged the name of an undercover CIA agent to columnist Robert Novak. This prompted a full-scale Justice Department investigation and created yet another media firestorm for Bartlett to handle.

But such rare indiscretions are the exceptions that prove the rule; the White House in general has been remarkably leakproof. Why? “It is mainly because there are not a lot of factions in the White House,” Bartlett said. “Under Clinton, and at times under Reagan, people were litigating their policy differences in the press. We don’t have a lot of that, thankfully.”

It all sounds like a nice, neat way of doing business, but does it really work? There are clearly benefits to the regimented control of information. An April 20, 2003, headline in the often-critical New York Times read “Even Critics of War Say the White House Spun It With Skill,” reflecting general admiration in the media for the way the Bush administration parceled out information. “Their communications operation is a very good one, and I am sure that it will be emulated in the future,” says Towson University professor Martha Joynt Kumar, who published an exhaustive study of the Bush communications operation in the June 2003 issue of Presidential Studies Quarterly. “Its main strength is coordination, not only of people but of ideas.”

But the Bush message machine is far from perfect, in part because of that lockstep approach. Its obsessiveness about control has spawned an office that has, as Washington Post media critic Howard Kurtz has suggested, “valued secrecy, hoarded information, and often viewed the press as hostile opposition.” The consequences, Kumar says, are undeniable: “While it is good to have such tight control over when the message gets out, how it is constructed, and how it is used, it also prevents you from hearing about trouble as fast as you might otherwise have. The sixteen-word episode is an example of the problem in listening. This should have bubbled up sooner as a problem.” There is also a reluctance to admit error. Says one member of the White House press corps: “The need to protect the president is so deeply burned into the DNA of these people that they just can’t admit they screwed up. To some extent Bartlett bears the blame for not seeing that they should drop the righteous defense of Bush.”

And then, increasingly, there is the question of whether the message itself is any good. In the months preceding the war, Bush was battered by negative stories suggesting that he was an ethically challenged businessman who knew more before September 11 than he let on about the prospects of a terrorist attack and stood a good chance of being a one-term president. This year, his approval ratings are falling because of uncertainties over Iraq, the ballooning deficit, and the sagging economy. And despite the considerable efforts of Bartlett and his cohorts, the administration has failed to persuade the Arab world that the Iraq war was one of liberation.

Bartlett appears unfazed by any of this. He says he is motivated by only one consideration: the approval and support of George W. Bush, to whom he remains profoundly loyal. “What I do is less about politics than it is about being driven by him, and liking him, and really wanting him to succeed,” Bartlett said. “I have been blessed. My introduction to politics and my life in politics so far has been entirely with one very successful politician.”

But what if he becomes less successful? What if Bush is defeated in his bid for reelection? What will he do then? He can’t imagine working for another politician, he says, and he doesn’t like the idea of working on Capitol Hill, where “it’s like trying to move a glacier.” He’s not interested in lobbying, and he won’t run for office himself. Which leaves Dan Bartlett exactly where he’s been for most of his life: With no particular plan for the future.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- George W. Bush