Out of my always-churning maelstrom of treasured Texas titles, these ten (listed in no special order) arise from my current reflections, either because the books are always with me—abiding voices like William Goyen’s and Sandra Cisneros’s—or because they’ve been important in my explorations of deep Texas time. Another sounding in another year might come up with other titles. I’ve chosen a catalog and an anthology for their value in presenting a host of artifacts and a range of literary statements; maybe someday I’ll get around to reading more Texas novels. On the fraught matter of making such a list, I’m reminded of J. Frank Dobie’s sage remarks at the opening of his Guide to Life and Literature of the Southwest. “Its emphases vary according to my own indifferences and ignorance as well as according to my own sympathies and knowledge.

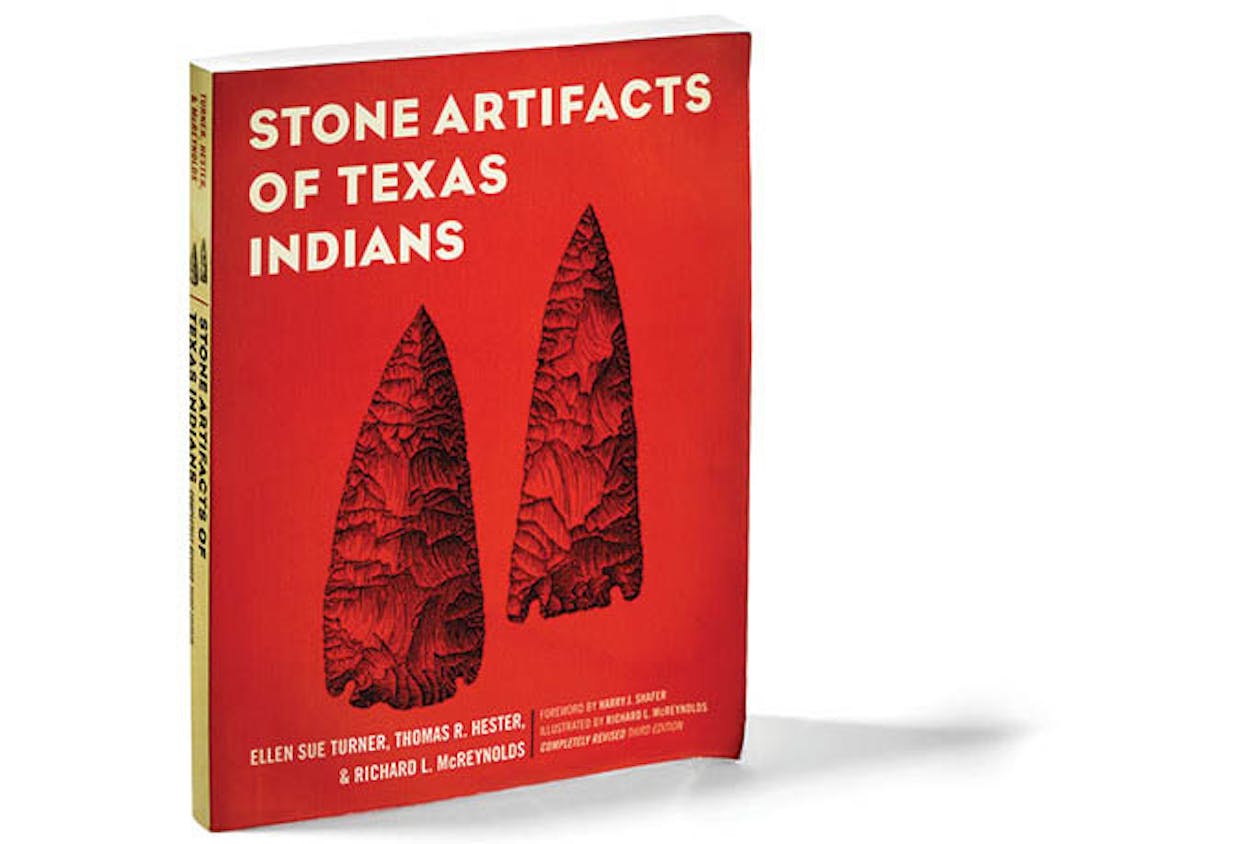

No. 1 Stone Artifacts of Texas Indians

This richly documented and illustrated catalog of exquisite drawings cleverly classifies the trove of points and spearheads that have been excavated across Texas, revealing the astounding variety and sophistication of cultures that have been present in these lands going back as far as 10,000 years ago. The authors refer to recent discoveries of human remains that also indicate how often these weapons were used not just against animals but other peoples, a testimony of how long homicide has been a mainstay around these parts. You’ll reconsider the notion that these lands were vast and unpopulated before the arrival of numerous settlers.

No. 2 Tongues of the Monte (1935) and A Texan in England (1945)

Perhaps these two lesser-known titles from the master of Texas letters appeal to me most because they represent Dobie out of his element, willing to spin his tales from unfamiliar threads. In Tongues, he is clearly spellbound by Sierra landscapes and quirky vaquero personalities, while his tales of British university eccentrics and pub life in Cambridge helped shape my expectations of how a Texan might navigate the English academy without coming off as superior or condescending. These books still exemplify for me the prospect of a Texas writer setting out into the greater world, whether on horseback or by some more modern transport, in search of story.

No. 3 With His Pistol in His Hand: A Border Ballad and Its Hero (1958)

In a spare, laconic style that can read as folksy as Dobie’s, Paredes pulls off an extraordinary literary feat with this tome, writing a folklor-istic study of the story of Gregorio Cortez— a ranch hand who shot a Texas sheriff in 1901—and debuting the practice of incorporating historically informed critical thinking that’s rooted in the experiences and language of South Texas Mexican Americans. Along the way, he exposes the racist underpinnings of Walter Prescott Webb’s characterizations (“a cruel streak in the Mexican nature”), and not even Dobie comes out of his analysis unscathed. It’s a book that opened the way for a host of voices to come.

No. 4 Empire of the Summer Moon: Quanah Parker and the Rise and Fall of the Comanches, the Most Powerful Indian Tribe in American History (2010)

Filling in a story that was once largely told from only one side, Gwynne’s deeply researched and stirring account of the life of Quanah Parker, the fierce mixed-blood Comanche chief who led his tribe’s last insurrections against advancing white settlers in the Texas Panhandle, is uncompromising in its depiction of the climactic battles on the High Plains. Gwynne moves from the Indians’ defeat to Parker’s heroic efforts to lead his people in the aftermath, uncovering a tale of radical hope—as well as a sense of the stories that still await in the hidden history of indigenous and mestizo Texas.

No. 5 Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans Into Americans (2003)

Johnson illuminates the all-but-lost history of the “Plan de San Diego” uprising of 1915, a call to arms for Mexicanos, blacks, and Native Americans to liberate U.S. territory from South Texas to California. Texas Rangers led the violent response, exacting a death toll that ran into the thousands; in an effort to help quell the upheaval, Mexican Americans created their first political organizations, such as the League of United Latin American Citizens. Amid today’s hype about the Valley’s future electoral importance, this book provides an invaluable glimpse into the region’s fractious political history.

No. 6 Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987)

It’s hard to overstate the impact of Anzaldúa, who was born in Raymondville, in creating a new understanding of Texan Chicana/Chicano identity. Her epoch-marking book incorporates echoes of Dobie, Paredes, and both Carlos Castañedas—the Texas historian and the California shaman—and combines autobiography, poetry, mystical imaginings, and biting indictments of culture and gender as she tries to conjure a new way for the mestiza/mestizo to think about self. Anzaldúa called this concept of identity Nepantlismo, a term inspired by the Aztec word “nepantla,” for the netherworld—a fluid space not unlike Texas itself.

No. 7 Hecho en Tejas: An Anthology of Texas Mexican Literature (2006)

This compendium, a historical survey of literary and artistic expression—including paintings, drawings, and popular songs—offers readers a deep look at the missing story of Texas. From the anonymous corrido tradition and the lyrics of Lydia Mendoza to the prose of John Rechy and the poetry of Rosemary Catacalos, this is a portable archive of a long-ignored but central literary tradition within the Texas epic. “I want this book to overwhelm the ignorance . . . about Raza here in Texas,” writes Gilb in the introduction, “the people who settled and were settled and still remain in Texas.”

No. 8 Woman Hollering Creek (1991)

Cisneros wasn’t born in Texas, but her rendering of the rasquache Tex-Mex vernacular is pitch-perfect in this short-story collection, which appeared just seven years after she arrived in San Antonio. Anchored in Mexico and Texas, these stories read like lapidary poems, telling of romance, revenge, carnal and spiritual longing, and whimsy. One story, written as a compilation of letters to various South Texas healers, saints, and virgins, ends with a confession by a woman that connects Texas, ancient Mexico, and divine universal forces. The book, still arresting today, expanded the way everyday life in Texas could be represented.

No. 9 The Secret School (1997)

In this fourth book of a series that recounts his abduction by, and interactions with, nonhuman entities he calls “the visitors,” Strieber recovers memories of attending a midnight “school” in the woods of San Antonio’s Olmos Basin. There, an alien grandmother teaches him and other children the history of the solar system, offering glimpses of the potentially tragic future for Earth. San Antonio place names and personalities abound; the city, always a crossroads of cultures, becomes a point of contact for alien worlds. As someone who grew up transfixed by NASA and trips to the moon, I find in Strieber’s work a city I recognize.

No. 10 The House of Breath (1950)

From the day I discovered this book on the shelf of Westfall Library, in San Antonio, Goyen’s debut novel has remained my greatest Texas read ever, a beacon of the infinite possibilities of literary voice—especially in capturing both the specificity and immeasurable abundance of everyday Texas. Plotless, meandering, at times unpolished and more often dreamlike, the work takes shape around explorations of place and identity as well as the underlying power of family. In one of the epigraphs to the book, quoting one of its characters, Goyen expresses a powerful version of the Question of Texas: “What kin are we all to each other, anyway?”