It’s been a cherished tradition for young students in San Marcos for almost a decade: The NASA Future Aerospace Engineers and Mathematics Academy (FAMA) summer camp. Last summer, COVID-19 prevented the children and teachers from gathering. But the program’s creator, Araceli Martinez Ortiz, Ph.D., got to work. She created “NASA Camp in a Box” and recruited Texas State University bilingual education students to help. The teachers-in-training modified five NASA experiments geared for kids in Kindergarten through 8th grade, gathered all materials the children would need to conduct the experiments at home, and included instructions in English and Spanish, so parents who don’t read English could help.

When a teacher can appreciate the life experiences of the students in their classes, they can use examples from the students’ lives to guide their learning more effectively.

This improvisational fix combined several of Dr. Martinez Ortiz’s passions: Getting teachers involved with culturally diverse students; getting parents involved in their children’s schoolwork; and, most importantly, getting science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education to young children in order to research their impact upon motivation and learning. Martinez Ortiz also wanted as many people as possible to benefit, so in addition to Texas, “NASA Camp in a Box” activities were sent to families in Illinois and Virginia.

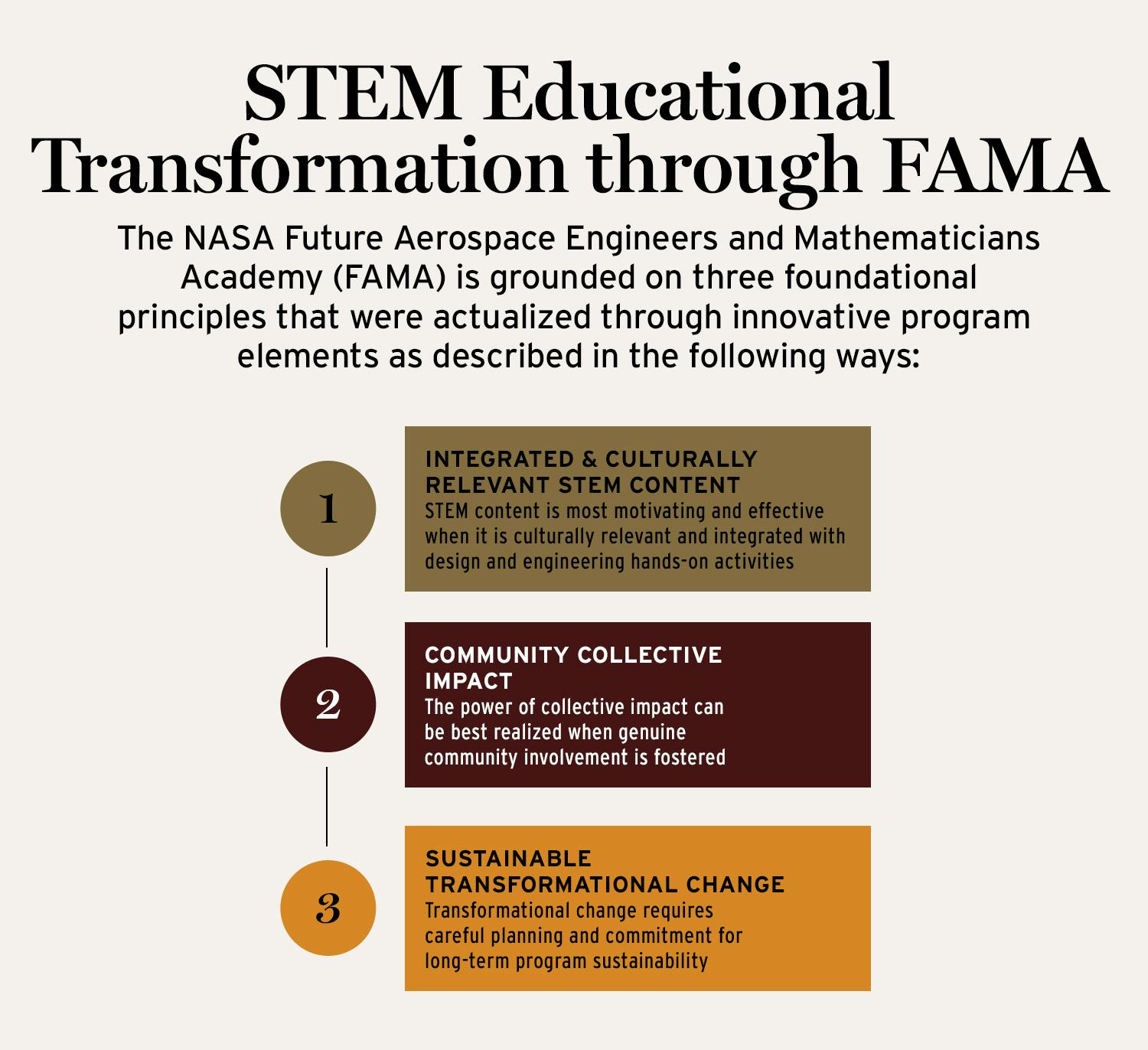

As Research Associate Professor of Engineering Education in the College of Education at Texas State University, and Executive Director of the LBJ Institute for STEM Education and Research, Dr. Martinez Ortiz has conducted numerous long-term studies that reveal how integrated science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) content efforts are needed to successfully encourage young students into STEM subjects and to go on to pursue careers in those fields. High on that list, she says, is the importance of teaching in the context of a student’s cultural background. Students are more motivated to learn STEM, her research shows, when the projects they are working on are culturally relevant to them.

“There may be children who haven’t had an opportunity to be on an airplane or enter a museum, or they haven’t seen snow. But they do have other experiences—they have been to their parents’ work sites, or they have been cooking alongside their parents since they were very young, or they know how to take a subway,” Dr. Martinez Ortiz says. “When a teacher can appreciate the life experiences of the students in their classes, they can use examples from the students’ lives to guide their learning more effectively. They can better help students build strong academic skills in math and science while motivating them to discover and learn in their own ways.”

When children are taught in the context of their daily lives, they are more engaged and encouraged: “When they are more engaged, they develop a closer tie to the subject matter and are more apt to consider future careers as scientists, engineers, and mathematicians” she says.

The research also shows that it is important for teachers to receive professional development consistently and in multiple modes so they are comfortable teaching STEM subjects. Further, it is necessary to get educators to teach the STEM subjects together, so children understand why they are learning how to read a graph, for example, not just how to do it.

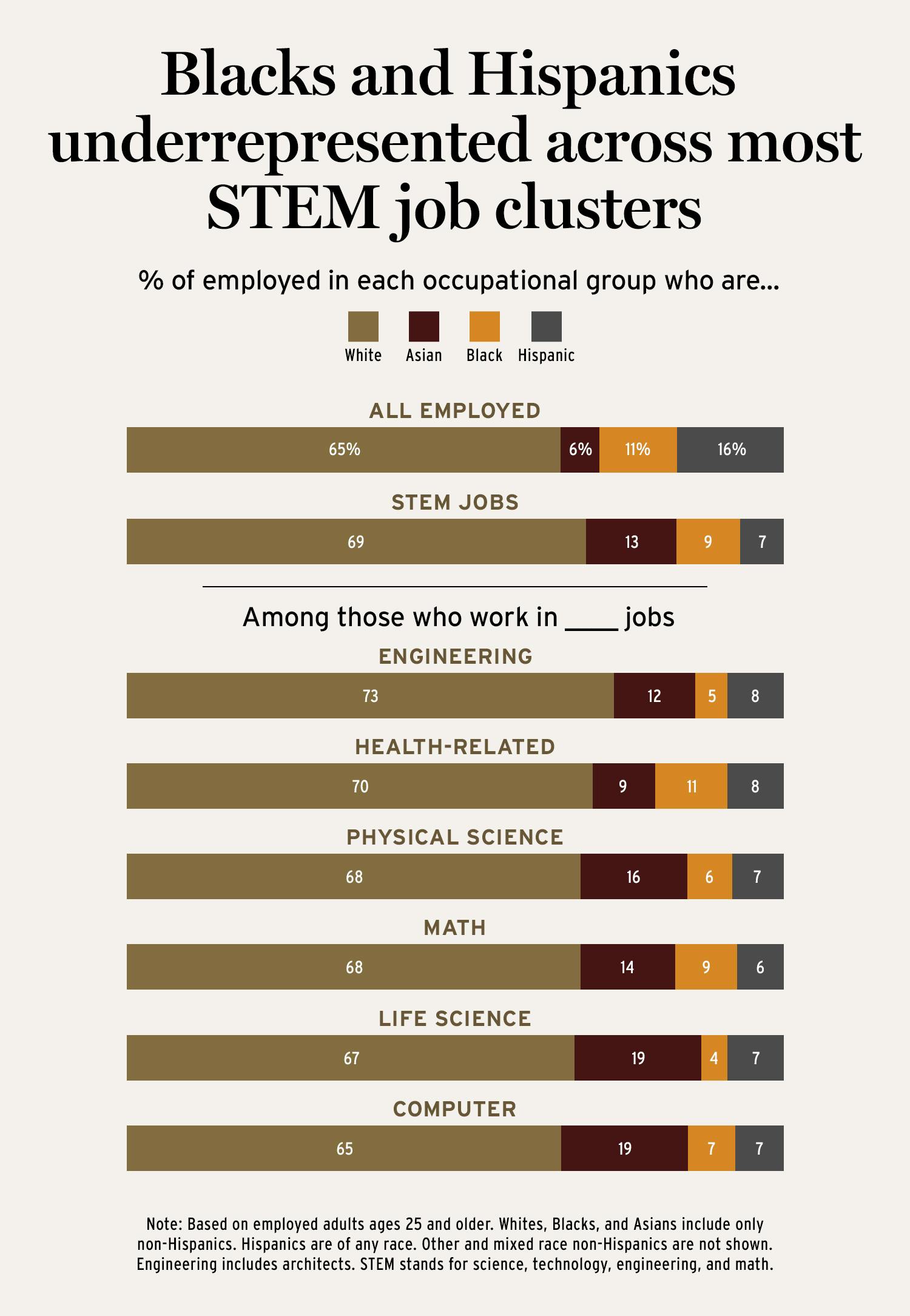

There is also a great need to focus on reaching all underserved populations, including girls who are too-often written off as being “unscientific,” and children in underfunded school districts in communities of color who suffer persistent inequities in education. It’s especially important, she adds, to break through historical roadblocks that keep African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, and other minorities from feeling welcome in STEM fields.

“We need diversity in these fields. Each of us can bring something unique and offer valuable insights based on our own unique experiences,” she explains. As she points out, higher-paying careers in STEM fields can lift a person out of poverty and can also help them raise up their families and their communities. “To inspire one parent or a set of educators or one child, that they can break free, and they can have many more opportunities—this can make such a difference,” she says.

Weaving STEM content together to solve problems, we show students that they aren’t just doing math equations, they’re helping deliver solutions to improve our world.

“People like Dr. Martinez Ortiz are very innovative,” says Samuel Garcia, an Education Specialist at NASA Kennedy Space Center, who works with the professor on getting NASA resources into the hands of educators around the country. “They are doing the right things for the right reasons, and no doubt transforming more of today’s students into a strong generation of STEM leaders and professionals. This work changes families, it changes communities, and it strengthens the STEM fields themselves, to have a variety of voices and backgrounds contributing.”

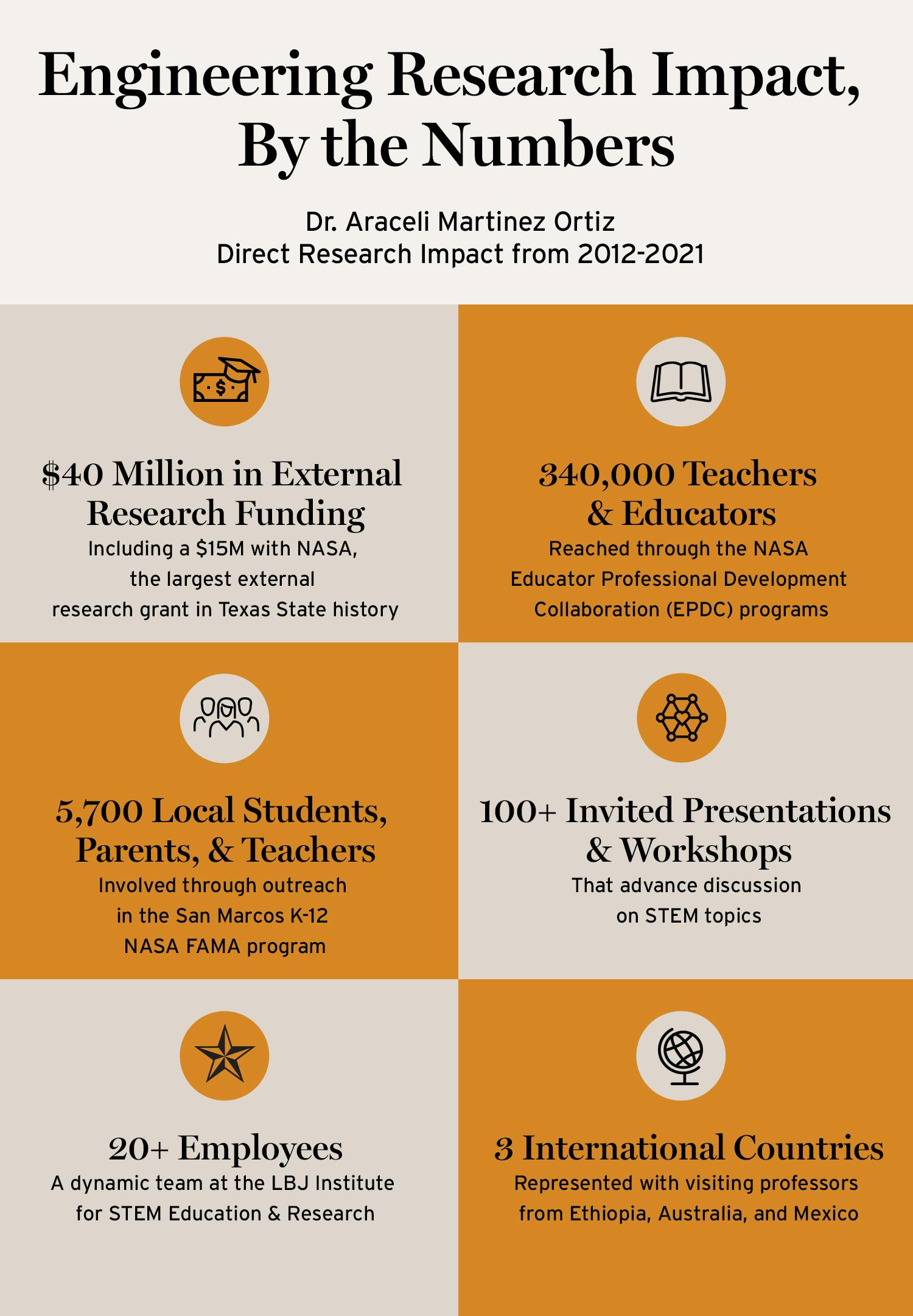

The need to get STEM to youngsters in underserved communities is what fueled the researcher to begin a small program eight years ago with Centro Cultural Hispano de San Marcos that would eventually become NASA FAMA. Dr. Martinez Ortiz designed the program to teach second- and third-graders science, engineering, and mathematics. Held at Centro, she called it “The Little Engineers” program. The first year there were ten children from grades 3 through 5. The following year, NASA funded the program, and the NASA Future Aerospace Engineers and Mathematicians Academy (FAMA) was born, serving more than one hundred children in grades 3 through 8.

The program, which turned into a joint partnership between Texas State University, NASA, Centro, and four regional school districts in central Texas, has served more than 5,600 students. The NASA funding will end this year, and the local schools in the program, along with Centro, will take over and continue to offer STEM summer or extracurricular programs. “Sustainability is very important for me,” says Martinez Ortiz. “I don’t want to just drop in, conduct my research, and leave. I look for partners who will develop programs with me, to best serve needs and so that when funding comes to an end, they can continue it on their own.”

Last year, the NASA FAMA program won the Phi Kappa Phi Excellence in Innovation Award and received $100,000. Dr. Martinez Ortiz gave most of that money back to her community partners in FAMA to offset costs of continuing the program in the coming years.

Keeping NASA FAMA and other programs going is key. As an educational researcher, Dr. Martinez Ortiz has authored numerous studies that show the earlier a child is exposed to STEM subjects, the more confidence the student will have to stick with the rigors of STEM projects and future careers.

“It takes time for a child to build interest, to get motivated, to change identity,” she says. “One summer program may not change a person’s life, but ten years of learning about STEM subjects and having support in that area will definitely help to give a student that possibility.”

Martinez Ortiz is still following some of her first “Little Engineers.” At least four of them who started in her program for second and third graders eight years ago, have attended the NASA FAMA camp every summer since and have now (in 10th and 11th grade) selected STEM subjects as their focus in high school. All four are girls.

“Students in middle school may say they don’t want to sit at a desk and do mathematics equations, but by integrating STEM subjects, we show them why they are learning that equation,” she says. “Through the lens of integrated STEM content, students learn how everything works together.”

“Weaving STEM content together to solve problems, we show students that they aren’t just doing math equations, they’re helping deliver solutions to improve our world,” she adds.

Martinez Ortiz says she has found that educators are often very open to this form of multi-subject, project-based inquiry by students, but that many seek deeper understanding to be more at ease with the STEM subjects themselves. She has developed training that, ideally, will get teachers as comfortable teaching technology and mathematics as they are with teaching reading. Sometimes this means giving teachers the experience she gives the Texas University student teachers—a chance to work directly with a community and to figure out ways to interest them in robotics, for example, or biology, or the moon in a way that is more personal to them. “We want educators to transfer joy when they teach STEM subjects,” she says.

Martinez Ortiz’s own joy in learning about—and now teaching how to teach—STEM subjects came from her own experiences. Born in Mexico City, she moved with her family to Detroit after her father was recruited to work at Chrysler during the Vietnam War. She didn’t learn English until she was six. In middle school, though, her world changed when she and her brother were asked to join an extracurricular learning program in engineering called The Detroit Area Pre-College Engineering Program (DAPCEP).

“The program was started by an African American mathematics professor named Kenneth Hill, and it was a game-changer for my family,” she says. “All of a sudden, we were learning there is something called engineering, there is something called computer science. Over the years all five of my brothers and sisters attended.”

The program led the future engineer and professor and her family members into science fairs and state mathematics competitions and gave them motivation to keep learning. Dr. Martinez Ortiz landed a seat in one of Detroit’s two math and science high school academies; later, she received a full scholarship to pursue her undergraduate degree in engineering. She then went on to get a master’s and a Ph.D. in engineering education.

After fifteen years working as an engineer, Dr. Martinez Ortiz wondered if she could have more impact in the STEM fields by ushering in a new generation of STEM experts. “When I was studying to be an engineer at the University of Michigan, there were almost no women or people of color in my upper classes. And it was the same at my jobs—I felt something was missing,” she says. “I felt it was my responsibility to do more.” Despite working full time, the professor earned a master’s degree in education and then went on to earn a Ph.D. in engineering education. “I also really enjoy serving as a mentor to encourage young women who wonder what it is really like to work in STEM and worry about how to balance raising a family, if that is their choice.”

Next up for Dr. Martinez Ortiz: She has been awarded a prestigious national faculty fellowship with NASA’s Office of STEM Engagement in Washington, D.C. She will be on loan from Texas State to advise and assist with NASA’s goal of “Building a diverse, skilled future STEM workforce.” Dr. Martinez Ortiz will be supporting NASA’s Artemis program, whose long-term goal is to send the next man and first woman to the moon by 2024. Among other activities, she will manage significant STEM education research elements with NASA Mission Directorates and will collaborate in the establishment of scalable and systemic approaches that broaden participation of underserved and underrepresented communities and institutions.

“I love the STEM fields, because the scientific literacy and critical thinking skills which are promoted by these subjects are important in order to be a well-informed citizen in our highly technical society,” says Dr. Martinez Ortiz. “So many of today’s great challenges in our society can be addressed by solutions that use a combination of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.”