It’s not that hard to write a song, really. Children do it all the time, humming tunes and making up words. So do countless songwriters in Nashville: melody, verse, chorus. Maybe a bridge. The world is absolutely cluttered with tales told in song, most under four minutes long. But what about a great song, one you can’t get out of your head, with verses that seem to be written about your own life and a melody that makes your heart feel as though it’s literally aching? A song you wake up mumbling, sing out loud when it comes on the car radio, mouth the words to when you hear it at the grocery store—then laugh when you see the person in line next to you doing the same thing? Great songs haunt us and arouse us; they make us think and feel in a way that no other art can, taking us to places we long to go every time we hear them. These are not the songs being churned out by staff songwriters. They’re something else entirely. So where do these great songs come from? The short answer—acquired after interviews with the writers of some of the state’s best-loved songs, the ones being sung at this very moment in cars and grocery stores all over creation—is that many of them began as happy accidents, spurred by a curious headline, a chance comment, a strange encounter. This happenstance led to a riff or a melody, maybe from an old blues ballad or a nursery rhyme twisted by memory. Then came a narrative, something about the girlfriend of a guy on the touch-football team or the fry cook who’s about to go fight in Iraq. Some of the songs, as the writers like to say, practically wrote themselves. Others were slaved over until the words and music were just right, the heart working with the head and the tune working with the lyrics to create a classic, a song that will live forever. From nothingness to immortality, these are the secret histories behind 25 great Texas songs. The stories, whether told by Willie Nelson or Augie Meyers, Kacey Musgraves or the Butthole Surfers, are as funny and weird, as heartfelt and tragic, as the songs themselves and may even change how you hear them. You might find yourself, for example, giving a shout-out to the TSU Tornadoes or Scarface’s grandmother. And you’ll definitely never listen to Gladys Knight again without thinking of Farrah Fawcett.

“Tighten Up” (1968)

Houston music in the sixties wasn’t all psychedelia; there was a thriving soul and R&B scene too. One of the city’s prime movers was Skipper Lee Frazier, a DJ on the black-owned soul station KCOH. Frazier also managed bands, including R&B dance band the TSU Tornadoes and vocal group Archie Bell and the Drells. In 1968 Frazier got the Tornadoes to record one of their biggest songs, an ebullient two-chord instrumental with a phenomenally catchy guitar riff, then brought the Drells front man into the studio to add words. “I can’t remember how many times we tried it, over and over again—maybe twenty-five or thirty takes—before Archie said ‘tighten up’ to everything,” Frazier wrote in his autobiography.

As Bell says in the song, the “tighten up” is a dance he and his pals started. But where Bell actually got the words is open to conjecture. Frazier claimed he wrote them. The Tornadoes’ drummer said they came from the trumpeter. And according to Bell, he wrote them himself: “Billy Butler, one of the guys in the [Drells], was dancing in the house one day, and I asked him what he was doing and he said he was doing the tighten up. I said, ‘I’m gonna write a song for that.’ ” Regardless of who wrote the words, it’s clear that the Tornadoes wrote the music. Yet when the 45 came out, it had only two composers listed: Bell and Butler.

“Tighten Up” eventually went to number one on Billboard’s Hot 100, taking Bell with it. Meanwhile, the Tornadoes soldiered on, bitter but wiser, until 1971, when they disbanded.

“Merry Go ’Round” (2012)

Several years ago Kacey Musgraves was on a ranch near Strawn, west of Fort Worth, writing songs with her friends Shane McAnally and Josh Osborne. She had put out a few indie albums in her teens, and now the 22-year-old was preparing for her major-label debut. While they worked, McAnally told a story about his mom, whose neighbor always had a bunch of cars out front. “I don’t know what they’re selling,” his mom had said, “Mary Kay or Mary Jane, but they’re doing something.” Musgraves latched onto the “Mary” theme, and the three began playing around with it. Soon the writers—who had all grown up in small towns, with Musgraves hailing from tiny Golden, in East Texas—found themselves heading down a melancholy path, their words outlining the experiences of rural folks trapped in lives of quiet desperation: “Mary, Mary, quite contrary, we get bored so we get married.”

Despite the desolate lyrics, the music had a lilting vibe that was almost sweet. “I liked the juxtaposition,” says Musgraves. “You don’t know what to feel when you hear it.” When she took the song into the studio, she wanted to preserve that lightness, so after it was recorded, she deleted instruments until she was left with a spare ballad pushed along by a gently percolating banjo. The label was reluctant to release the bleak song as a single, but Musgraves was insistent, having seen fans’ reactions at shows. “People kept coming up to me and saying, ‘This is my life.’ ” She was right: after its release, fans went crazy for “Merry Go ’Round,” and it won a Grammy in 2014. She understands why people connected so strongly with the song and insists she didn’t mean it as a knock against small towns or the people in them. “Everybody’s got their distractions and vices,” she says, “but we’re all walking the world trying to figure out what to do.”

“Midnight Plane to Houston” (1972)

Jim Weatherly, a budding songwriter, was living in Los Angeles in the late sixties when he met Lee Majors, a budding actor. The two became friends, bonding over football, which they had both played in college. Weatherly also befriended Majors’s girlfriend, a former University of Texas student (and budding model) named Farrah Fawcett. One day in 1970, Weatherly called Majors and Fawcett answered the phone. Majors wasn’t home, she said, and she was packing her suitcase to take a “midnight plane to Houston” to visit her family.

Weatherly was struck by the phrase—“It was an automatic song title,” he says—and as soon as he got off the phone, he picked up his guitar. He imagined his friends as the song’s protagonists: after struggling to make it in L.A., Fawcett was flying back home to Houston; Majors, preferring to live with her in her world than live without her in his, was following her. “Midnight Plane to Houston” took less than an hour to write, but Weatherly knew he had something. His friends liked it too, though they had no plans to flee L.A.

Weatherly recorded and released the song on RCA Records. Soul singer Cissy Houston—Whitney’s mother—heard it and recorded her own version, with a few changes. “My people are originally from Georgia,” she said later, “and they didn’t take planes to Houston or anywhere else. They took trains.” Weatherly’s publisher sent Houston’s version to Gladys Knight & the Pips, who recorded the song in 1973. Knight, who at the time was in a troubled long-distance marriage, turned the song into a megahit. Decades later, in 2003, Weatherly rerecorded the song. Though he was tempted to do it as originally written, he gave in to history and sang the song as it had become: “Midnight Train to Georgia.”

“La Grange” (1973)

The riff was borrowed, the lyrics were blue, the song was irresistible. Inspired by a whorehouse and named for the town where it was located, “La Grange” turned a Houston boogie band into one of the biggest groups on the planet. Edna’s Fashionable Ranch Boarding House (commonly known as the Chicken Ranch, because the original madam had raised chicks, hoping to disguise it as a poultry farm) had been open since 1905, frequented by politicians, businessmen, and teenage boys, including the future members of ZZ Top. “There was a space set aside in every young Texan’s life to get a fake ID to get into La Grange,” said singer and guitarist Billy Gibbons in 1984. “You’d have to get yourself together to confront the line of girls on the couch, all with their legs crossed in the same direction and swinging their legs to the same beat.” Bassist Dusty Hill later remembered, “You couldn’t cuss in there. You couldn’t drink. It had an air of respectability. Miss Edna wouldn’t stand for no bullshit.”

“La Grange” was released on the album Tres Hombres in July 1973; a month later the Ranch closed, though not because of the song. Acting on a tip from the attorney general’s office, a TV station in Houston had been airing a series of investigative reports on the establishment, which led Governor Dolph Briscoe to order it shut down.

Nearly two decades later, in 1992, ZZ Top did get in some trouble over the song: they were sued by the publisher of “Boogie Chillun,” the John Lee Hooker song whose relentless guitar riff had formed the basis for “La Grange.” But Hooker himself bore no hard feelings. “They’re very good people,” he said at the time. “They’re fans of mine, and I’m a fan of theirs.” A court eventually ruled in favor of the Top, finding Hooker’s song to be in the public domain.

“Up to the Mountain (MLK Song)” (2006)

In 2003, while watching a PBS documentary on Martin Luther King Jr., Patty Griffin found herself moved to tears by the reverend’s final speech, on the eve of his assassination, in which he spoke of having been to the mountaintop and seen the promised land. A week later, the Austin musician was reading in bed when she heard a voice in her head; it sounded a lot like Pops Staples, the patriarch of the legendary gospel and soul group the Staples Singers. “I went up to the mountain,” the voice sang, “because you asked me to.” Griffin got out paper and pen, and the words and the tune kept coming—so fast, in fact, that she thought she must be stealing the song from somewhere. When she finished, she titled it “Up to the Mountain (MLK Song)” to acknowledge King and his speech.

Griffin made a demo, which the soul singer Solomon Burke heard, and he recorded the song in 2006, with Griffin singing backup. In 2007 Kelly Clarkson performed the song on American Idol, making it an overnight hit as well as the go-to selection for others intent on showcasing their pipes, including Susan Boyle, who covered it on her debut album. Then the song found a purpose more in line with its origins, when it was sung by the Boston Children’s Chorus, with Yo-Yo Ma on cello, for the televised Interfaith Prayer Service following the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. Survivors, first responders, and other witnesses to the bombing filled the cathedral where the service was held; President Barack Obama also attended. “Writing songs and then performing them is a weird thing to do for a living,” Griffin says. “I’m never exactly sure I should even be doing this. But when I heard the song done that way, I felt so honored to do what I do. It was helping people grieve and feel better and transcend the terrible thing that had happened.”

“The Front Porch Song”/ “This Old Porch” (1984)

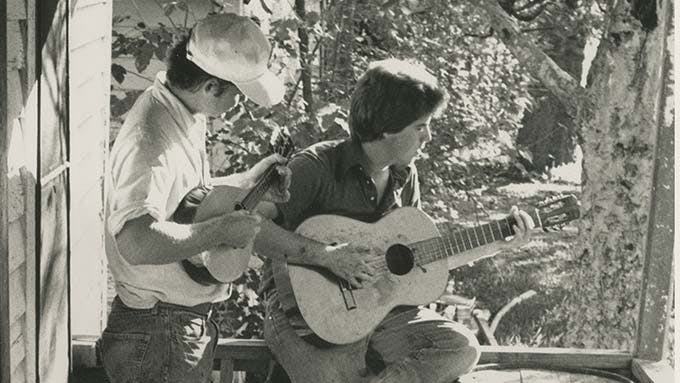

In the mid-seventies, Robert Earl Keen, an English major at Texas A&M (class of ’78), could often be found on the front porch of his rented house in College Station, playing bluegrass and country songs with friends while studious cadets and future engineers bustled past. Every so often a journalism major named Lyle Lovett (class of ’79) would ride up on his ten-speed, lean it against the porch, and listen. The two music geeks, who were each just starting to write songs, soon became friends.

One day as Keen sat on the porch, strumming some chords, he started thinking about the porch and what it meant to him. He wrote three verses, first likening the porch to a bull, then to a plate of enchiladas from Bryan’s LaSalle Hotel, and finally to an old local movie theater. Keen knew as he sang that this song was different from the ones that had come before. “I realized, here’s where I have to go to be a songwriter,” he recalls. “I have to be real, colorful, dramatic.”

Keen played the song for Lovett, who liked it so much that he learned to play it too. As he did, Lovett found himself thinking about Keen and his relationship with his landlord, the man who owned the porch. He was a little overbearing, says Lovett. “He’d walk right in, make himself at home. But Robert treated him like he belonged there, and he’d go help him move his cattle or build a fence. I admired that.” Lovett thought the only thing the song was missing was Keen himself, so he added some lines about his friend and the old man. Then, for the final verse, he brought the song around to the two guys singing it—slacker songwriters in a town full of serious students—ending on a note of defiance.

Looking back, Lovett says, “I’m as proud of that verse as anything else I’ve ever written. I was able to say exactly how I felt.” Keen loved the new parts too. “Before, I had a riff on what this porch was all about. The song didn’t breathe until Lyle got to work on it.” Each singer put the song on his first album, Keen’s version (“The Front Porch Song”) outgoing, Lovett’s (“This Old Porch”) wistful. Today the porch and the house it fronted are gone, but the song, which both still play in concert, remains, a nod to two young musicians determined to make their way in the world.

This old porch is just a long time

Of waiting and forgetting . . .

And remembering the falling down

And the laughter of the curse of luck

From all of those passersby

Who said we’d never get back up.

Looking back, Lovett says, “I’m as proud of that verse as anything else I’ve ever written. I was able to say exactly how I felt.” Keen loved the new parts too. “Before, I had a riff on what this porch was all about. The song didn’t breathe until Lyle got to work on it.” Each singer put the song on his first album, Keen’s version (“The Front Porch Song”) outgoing, Lovett’s (“This Old Porch”) wistful. Today the porch and the house it fronted are gone, but the song, which both still play in concert, remains, a nod to two young musicians determined to make their way in the world.

This Old Porch: Words and music by Lyle Lovett and Robert Earl Keen Jr. ©1986 Michael H. Goldsen, Inc., Lyle Lovett Music and Keen Edge Music. All rights for Lyle Lovett Music controlled and administered by Michael H. Goldsen, Inc. All rights for Keen Edge Music administered by BMG Rights Management (US) LLC. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard Corporation.

“Mind Playing Tricks on Me” (1991)

“I was in a real f—ed-up state of mind, to the point where I just wanted to die.” That’s how Scarface would later describe his mental well-being back in 1990, when he wrote the Geto Boys’ biggest hit. Just nineteen years old at the time, the Houston rapper was living with his grandmother, who knew him as Brad Terrence Jordan. He’d had a rough youth, and his struggles with manic depression and regular drug use—LSD, mushrooms, weed, paint, glue—had left him deeply unsettled. One day, he heard his grandmother mumble something to herself. When he asked what she was talking about, she replied, “Oh nothing, my mind’s just playing tricks on me.” Scarface could relate. He also knew a hook when he heard one, so, pen in hand, he let his own mind take over.

In the studio, Scarface added a breezy guitar riff sampled from Isaac Hayes’s “Hung Up on My Baby,” and the song appeared on the Geto Boys’ 1991 album, We Can’t Be Stopped. The disturbing and violent track—helped by the album’s cover art, which featured a photo of band member Bushwick Bill in a hospital bed after getting his eye shot out—made it to number 23 on Billboard’s Hot 100. More important, it let the world know there was more to rap than East Coast and West Coast. Houston hip-hop had arrived.

At night I can’t sleep, I toss and turn

Candlesticks in the dark, visions of bodies bein’ burned

Four walls just starin’ at a nigga

I’m paranoid, sleepin’ with my finger on the trigger.

In the studio, Scarface added a breezy guitar riff sampled from Isaac Hayes’s “Hung Up on My Baby,” and the song appeared on the Geto Boys’ 1991 album, We Can’t Be Stopped. The disturbing and violent track—helped by the album’s cover art, which featured a photo of band member Bushwick Bill in a hospital bed after getting his eye shot out—made it to number 23 on Billboard’s Hot 100. More important, it let the world know there was more to rap than East Coast and West Coast. Houston hip-hop had arrived.

“Pretty Paper” (1963)

Before Willie Hugh Nelson became Willie, he had to hustle for a living like any musician. As a young singer in Fort Worth, he worked selling encyclopedias and vacuum cleaners door-to-door. Some days, when his work took him downtown, he’d see a disabled man dragging himself along the sidewalk on his hands and knees, wearing kneepads made from old tires. The man would make it to Leonard’s Department Store, sit outside the big glass doors, and sell pencils to passersby from a customized leather vest. At Christmastime, he’d hawk ribbons and gift wrap, calling out, “Pretty paper!”

A few years later, after Willie had moved to Nashville, he was walking around his farm when he had a vivid memory of the street vendor. He picked up his guitar and composed a ballad, contrasting the holiday shoppers’ joy and mirth with the man’s apparent loneliness and misery: “In the midst of the laughter, he cries.” Willie says the song took him only twenty minutes. “It was an easy song to write. The easy ones write themselves.” Soon after, “Pretty Paper” was recorded by Roy Orbison, and it’s been a holiday classic ever since.

Willie didn’t know it, but the man’s name was Frankie Brierton. Born with spinal meningitis, he learned early on to get around on his hands and knees; later he’d drive himself to the department store every day in a car he had outfitted with hand-operated controls. His daughter Lillian Compte says he refused all offers of government assistance. “He didn’t want to depend on anybody. He wanted to be on his own and take care of his family.” Brierton sold pretty paper in downtown Fort Worth for years and died in 1973 having never heard Willie’s song. His daughter says he was anything but lonely or miserable, though. “He was married seven times.”

“Bubbles in My Beer” (1947)

Cindy Walker, born in Mart, east of Waco, was one of country music’s most prolific songwriters, turning out hundreds of songs, many of which became standards. Her songwriting methodology was simple: start with a good title and the song will essentially write itself. “The title tells the story,” she once said. “If you can get a real good title, you’ve got something.”

One of her early champions was Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, who recorded more than fifty of her songs. In 1947 Tommy Duncan, the singer for the Playboys, called her with an idea for a title: “Watching the Bubbles in My Beer.” As she later recalled, “I couldn’t have been more surprised if he had hit me in the face with a wet squirrel. I said, ‘You’re kidding,’ but I could tell by the silence on the other end of the line that he wasn’t kidding.” According to Walker, Duncan went on to describe “a lonely man sitting in a barroom not talking to anyone, just thinking of someone or something that happened in the past—just remembering and watching the bubbles in his beer.” Walker got to work, and the resulting song became one of the all-time great barroom weepers.

Walker died in 2006, just nine days after Willie released a tribute album, You Don’t Know Me: The Songs of Cindy Walker. The first song on the album? “Bubbles in My Beer.”

“You’ll Lose a Good Thing” (1962)

Barbara Lynn was a teenager in Beaumont, playing in blues bands around southeast Texas and making a name for herself as a left-handed female guitarist, when she started dating a young man named Sylvester. One night, Lynn came upon him talking to another girl. She was devastated. As she recalls, “He said, ‘Wait, this is my friend’ or ‘my sister’ or something. I said, ‘Sylvester, if you lose me, you’ll lose a good thing.’ I cried that night, but I woke up the next morning and wrote that song.” She put her ultimatum to a catchy melody, punctuated in the middle by a confident “oh, yeah.”

After high school, Lynn caught the ear of Houston producer Huey Meaux, who saw her play in a club. He drove her to New Orleans and put her in a studio, where she recorded “You’ll Lose a Good Thing.” The song opened with a throaty saxophone that led to a sexy, quietly lurching rhythm, over which Lynn sang her plaintive yet defiant vocal. The song’s attitude and memorable chorus took it to number eight on Billboard’s Hot 100, and it went on to be covered by everyone from Freddy Fender to Aretha Franklin, who sang the hell out of it. But no one could capture the emotion of the woman who had spoken that original line.

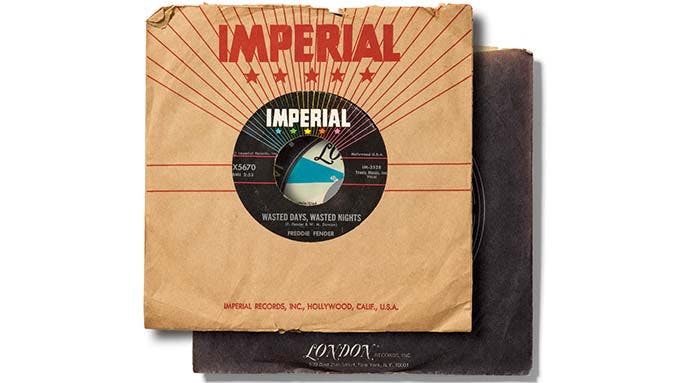

“Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” (1960)

Born and raised in San Benito, Baldemar Garza Huerta soaked up all kinds of music from the Valley—R&B, blues, conjunto, country. As a teenager he dreamed of being a star; he even had moderate success south of the border with Spanish-language recordings of songs by Elvis, Harry Belafonte, and Hank Williams. But he wanted to be big in America, so in 1959, at age 21, he changed his name, and Freddy Fender was born.

Not long afterward, he was playing at the Starlight Club, in Harlingen. He was broke and miserable. “I was staying in a little room there at the bar,” he later recalled. “I was down-and-out, feeling very sorry for myself. My marriage was on the rocks and I was separated.” He sat down and started writing, the diction guided by his experience: “Wasted days and wasted nights, I have left for you behind.” Fender explained, “I don’t think that an Anglo American would write a line like that. But in Spanish, it would be very correct.”

He recorded a smoky R&B version that became a minor hit in 1960, but a marijuana bust a few months later sent him to prison for three years. By the time he got out, his career was seemingly over, though he continued to play music part-time. In 1975 Fender managed to score a huge hit with “Before the Next Teardrop Falls,” and afterward he rerecorded “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights,” which this time went to number one on the country charts. His teenage dream had finally come true.

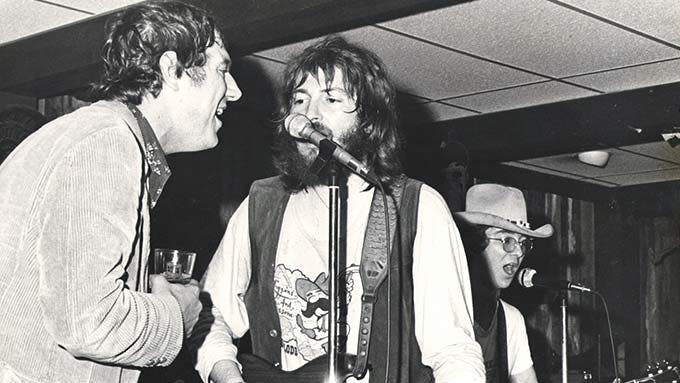

“Redneck Mother” (1973)

In the early seventies, Ray Wylie Hubbard lived in Dallas but spent his summers in Red River, New Mexico, playing music with other long-haired expats, like Texans B. W. Stevenson and Bob Livingston. There were only two places to buy beer in town, a hippie bar and a redneck bar, and one afternoon, when it was Hubbard’s turn to make a beer run, he decided to go to the redneck joint, the D-Bar-D, because it was closer.

He regretted it immediately. “I walked in and there were thirty or forty people drinking, including one old woman,” he recalls. “The jukebox stopped and they all turned and looked at me.” He nervously asked the bartender for a case, and while he waited, he found himself getting baited by the woman and her son. “How can you call yourself an American with hair like that?” she asked. Her son added, “You want me to beat him up?” Hubbard got his beer and fled, but not before eyeing a pickup truck in the parking lot with a gun rack and a redneck bumper sticker. Once he was safely back with his pals, he picked up his guitar, strummed a G, and made up a song on the spot, about a redneck mother whose son was “thirty-four and drinking in a honky-tonk, just kicking hippies’ asses and raising hell.”

Hubbard eventually returned to Dallas and forgot about the song until a year later, when he got a call from Livingston, who was playing bass with Jerry Jeff Walker. Livingston had performed the song for Walker, who wanted to record it. But it needed another couple of verses. So, standing in his parents’ bedroom, phone to his ear, Hubbard once again made up some lines on the spot, about the pickup he’d seen in the parking lot, the gun rack, and a “Goat ropers need love too” sticker.

Walker included the song on his album ¡Viva Terlingua!, jump-starting Hubbard’s career. “If I hadn’t gone into the D-Bar-D,” says Hubbard, “that song never would have existed. It’s so strange that it all happened, still kind of a mystery.”

“I Summon You” (2005)

Britt Daniel is not a typical songwriter. He doesn’t tell stories, and he constructs verses and melodies out of the sounds of words as much as their meanings, sometimes taking weeks or even months to finish a song. The results are riffy and imagistic. But in the fall of 2003, Daniel’s methods were failing him, and he was having a hard time composing new material. One day, as an exercise, he began stringing together different chords, one after another. “I’d play the chords in a progression, get to the end, and think, what could fit here?” he recalls. “Then I’d add another one.” He kept going until he had eighteen chords in a row.

He broke for lunch, and when he returned, he began tossing out words while he played. He was lonely and moody at the time, missing a woman he had dated over the summer who had moved away, and phrases like “where are you tonight?” and “eight hundred miles is a drive” offered themselves up. Before he knew it, Daniel was at the end of the string of chords, at which point he recalled something he used to half-jokingly say to his girlfriend on the phone in the days after she left: “I summon you.” The words fit perfectly, forming a sweet kicker: “I summon you to appear, my love.”

Daniel knew the song was different from others he had written, and not just because he had finished it in a single afternoon. When it came time to record, he borrowed his father’s classical guitar, strumming with a bouncy rhythm rarely heard in Spoon’s wiry, angular songs, and the song became a standout on the group’s fifth album, 2005’s Gimme Fiction. “I’ll probably be playing this song for the rest of my life,” Daniel says. “It has a melancholy to it, the chords don’t sound like anything I’ve ever done, the words are far-out yet emotional—some I know exactly what they mean, others I’m still figuring out.”

“Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” (1994)

Selena was fast becoming a major star but didn’t have much experience as a composer when she helped write her most famous song. In 1992 she and her band were on tour supporting her breakout album, Entre a Mi Mundo. One afternoon during a sound check, while bassist A. B. Quintanilla (Selena’s older brother and bandleader) jammed with guitarist Chris Perez (Selena’s husband), Selena joined in, singing made-up phrases like “itty bitty bubbles.” Over the next few sound checks, she and the band returned to the nascent tune. Backup singer Pete Astudillo remembers Selena singing, “If I was a fish, under the sea, I would swim, swim, swim to you.” Eventually, Quintanilla realized they had the rhythm and melody of a great song—they just needed some actual lyrics. So he asked Astudillo, a native Laredoan who had already penned a couple of hits for Selena, to write them. Astudillo obliged, using Selena’s idea but taking the song from sea to land. “Itty bitty bubbles” became “bidi bidi bom bom,” the sound a young woman’s heart makes every time her crush is near.

The band recorded the song at Selena’s father’s Corpus Christi studio, giving it a cumbia-reggae-pop feel that, led by Selena’s playful vocals, took it to number one on Billboard’s Hot Latin Tracks. And it turned out to be the only song Astudillo would ever write with Selena. “If we had actually sat down and tried to write a song together,” he says, “I don’t think it would have happened.”

Cada vez, cada vez que lo veo pasar

Mi corazón se enloquece

Y me empieza a palpitar

Bidi bidi bom bom.

[Each time, each time that I see him go by

My heart goes crazy

And begins to pound and beat

Bidi bidi bom bom.]

The band recorded the song at Selena’s father’s Corpus Christi studio, giving it a cumbia-reggae-pop feel that, led by Selena’s playful vocals, took it to number one on Billboard’s Hot Latin Tracks. And it turned out to be the only song Astudillo would ever write with Selena. “If we had actually sat down and tried to write a song together,” he says, “I don’t think it would have happened.”

Bidi Bidi Bom Bom: Lyrics printed with permission.

“New San Antonio Rose” (1940)

The biggest recording of Bob Wills’s career—the one that led him to be crowned the King of Western Swing—had no fiddles on it at all. But the song didn’t begin its life that way. In 1938 Wills and His Texas Playboys were at a recording session in Dallas when their A&R man, the English-born Art Satherley, asked Wills if he had any more tunes like “Spanish Two-Step,” an instrumental fiddle number he had written and recorded in 1935. “No, I don’t,” said Wills, as he later recalled, “but if you give me a few minutes, maybe I can come up with something.” He set to work right there in the studio, picking out some of the melody lines from the bridge of “Spanish Two-Step,” and before long he’d arranged a new tune. He and the band recorded it immediately, with the fiddle taking one solo and the steel guitar taking another. When Satherley asked what the new tune was called, Wills, who hadn’t thought that far, told him to go ahead and name it. Satherley, who had a fondness for Texas place names, christened it “San Antonio Rose.”

The song became a regional hit and got the attention of bigwigs at the New York music publishing company owned by famed songwriter Irving Berlin. The firm wanted to publish the song and give it a wider audience, but only if Wills wrote lyrics for it. Though Wills wasn’t much of a lyricist, he cobbled together some words with help from his band, and in 1940 he and the Playboys went back into the studio. The band, by this point, had grown to include eighteen instruments (including five saxophones and two trumpets) and sounded as if it could have been backing Glenn Miller—until Playboy Tommy Duncan opened his mouth. Aiming for a big-band pop sound, the Playboys didn’t use fiddle or steel guitar on the updated version, which they titled “New San Antonio Rose.” The song became a smash hit, bringing international attention to the rest of Wills’s music (the stuff with fiddles on it) and propelling him to superhero status. Inspired by this success, Wills redid “Spanish Two-Step” a few years later, again adding lyrics. The name? “New Spanish Two-Step.”

“Travelin’ Soldier” (1996)

In the fall of 1990 Bruce Robison was working as a fry cook at an Austin diner and writing his first songs. That August, Iraq had invaded Kuwait, and the United States was preparing for a massive counterinvasion. Robison learned that one of his buddies at the diner, another fry cook, was being called up to active duty. The news reports during those months were full of casualty estimates, and Robison found himself contemplating the unthinkable: dying young in war. Then he started writing about something even more unbearable: dying young while being in love. The first thing to come to him was a melody—the soaring opening of the chorus—and Robison shoehorned in some words: “I-I-I-I cried, never gonna hold the hand of another guy.” Details quickly followed: a lonely boy leaving for war after high school (Robison changed the setting to Vietnam), a shy girl (“a piccolo player in the marching band”) falling for him, the love between them growing even as they are thousands of miles apart. For the final verse, as the girl cries alone because her soldier has died, Robison recalled a familiar spot, the space beneath the stadium bleachers at Bandera High, where he had gone to school.

Robison knew “Travelin’ Soldier” was good—he included it on his first album, in 1996—but he didn’t know how good until early 2003, when fellow Texans the Dixie Chicks took it to number one on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles and Tracks chart. With the United States again on the brink of war, singer Natalie Maines’s emotional vocals caught the pathos at the heart of the song—she sounded like the girl left behind. Then in March, at a concert in London, Maines uttered the infamous words that would destroy her band: “We do not want this war, this violence, and we’re ashamed that the president of the United States is from Texas.” The fallout was swift: within a few weeks the song had dropped completely off the charts.

“Travelin’ Soldier” lives on, though. When Robison plays it today, men stare and women weep, and sometimes they give him a standing ovation. “I wish I knew how to do it again,” he says of the song he created a generation ago. “I was just starting, had no concept of what I was doing. I remember Robert Duvall talking about the line between drama and melodrama being very fine. You get older and you’re too self-conscious to dance along that line anymore. But on ‘Travelin’ Soldier,’ I got damn close to melodrama.”

“Pepper” (1996)

The Buttholes didn’t do story songs. They did punk songs, noise songs, art songs, absurd songs. And yet their one major hit was not only a narrative but was also based on real people—unlike the folks in, say, “I Saw an X-Ray of a Girl Passing Gas.” “Pepper,” which originated as a recorded drumbeat and a guitar riff by Paul Leary, drew on the memories of singer Gibby Haynes, who scribbled out lyrics about people he had known as a teenager in Dallas (Mikey, Sharon, another Mikey, and “the ever-present football player rapist”) who’d lost limbs and lives to fights, car crashes, and AIDS. The one thing they’d had in common: “They were all in love with dying, they were doing it in Texas.”

Haynes sang and rapped the words, Leary played a distorted guitar solo, and the group added a bridge with backward vocals, which Leary remembers worried their label, Capitol. “They were uptight about knowing what was being said. They didn’t want some kid killing himself.” (In fact, the bridge’s words came from the singsongy chorus: “I don’t mind the sun sometimes, the images it shows.”) “Pepper” hit number one on Billboard’s Modern Rock Tracks chart, though the song’s success angered some longtime fans, who thought it a betrayal of the group’s scrappy roots. “Yeah, but who cares,” says Haynes. Leary agrees. “We were never a punk band. We were always a schlock band.”

As for the song’s title, Haynes says, “One time a guy came up to Teresa, one of our drummers, while she was walking the band’s dog and asked, ‘What’s your dog’s name, sonny . . . Pepper?’ ”

“Hey Baby, Que Paso?” (1990)

Once upon a time, Augie Meyers and his childhood friend Doug Sahm were rock stars with the Sir Douglas Quintet. That time, of course, was the sixties. But by 1986 Sahm had decamped to Canada and Meyers was sleeping on his son’s couch in San Antonio, playing the accordion with friends and dating a woman who didn’t share his taste in music. “Why are you always playing that Mexican music?” she’d ask. “I like it,” he’d respond. After their inevitable falling-out, Meyers kept hearing a phrase running through his head: “Hey, baby, qué pasó? ” He began writing lyrics around it, incorporating both Spanish and English words, as well as a sort of pidgin that he created as he wrote. Fifteen minutes later, he had a new song: “Kep Pa So,” a nod to his recent time living in Sweden, where he’d often found himself communicating phonetically. Meyers released the song on his own label, Super Beet; soon after, it was rereleased nationally by Atlantic Records and got airplay all over the country.

In 1988 Sahm returned to Texas with an idea: a Tex-Mex supergroup, with friends Flaco Jiménez and Freddy Fender joining him and Meyers. The group would be called the Texas Tornados. For their first album, they redid Meyers’s song, though Fender told him his neologisms weren’t going to work. “These were words I made up,” remembers Meyers, “and they were trying to sing them but kept saying, ‘What does this mean?’ ” He converted everything to English or Spanish, and the retitled “Hey Baby, Que Paso?” was once again a hit. It also became, as Sahm introduced it at live shows, “the National Anthem of San Antonio.”

“Life by the Drop” (1991)

From boyhood in Dallas to adulthood in Austin, Doyle Bramhall and Stevie Ray Vaughan were friends, playing in bands and dreaming of the big time. Bramhall was a songwriter as well as a drummer, and he and Vaughan often wrote together; one of their early songs, “Dirty Pool,” made it onto Vaughan’s first album, 1983’s Texas Flood. Over the next few years, their paths diverged—one man playing stadiums, the other playing bars—yet the two remained close. Eventually Bramhall began writing a song about their friendship:

“Doyle wasn’t jealous,” says Barbara Logan, who was Bramhall’s wife. “He was proud of Stevie. It was a dream they had both had, and now Stevie was living it.” Though the men had their problems with drugs and alcohol, Logan says that’s not what the song was about. “It was about living life day by day, one drop at a time.”

In 1988 Vaughan decided to record the song, which Bramhall had never quite finished. Bramhall told Logan they needed a third verse, and though she’d never written a song before, she composed some lines on the spot about two friends taking a walk together, happy to be alive. Vaughan recorded the song on a twelve-string acoustic; it wasn’t released until a year after his 1990 death, however, when his brother, Jimmie, put together a posthumous album, The Sky Is Crying. After a career playing the sturm und drang of electric blues, “Life by the Drop” stood as a pure and simple coda, with Vaughan singing the words written by his faithful friend. “He was very proud of that song,” Logan says of Bramhall, who died in 2011. “It speaks to so many people in so many ways. Songs are like that—that’s something I learned from Doyle. Everybody hears songs in their own way.”

You went your way and I stayed behind

We both knew it was just a matter of time

You’re living our dreams, oh, you on top . . .

That’s how it happens living life by the drop.

“Doyle wasn’t jealous,” says Barbara Logan, who was Bramhall’s wife. “He was proud of Stevie. It was a dream they had both had, and now Stevie was living it.” Though the men had their problems with drugs and alcohol, Logan says that’s not what the song was about. “It was about living life day by day, one drop at a time.”

In 1988 Vaughan decided to record the song, which Bramhall had never quite finished. Bramhall told Logan they needed a third verse, and though she’d never written a song before, she composed some lines on the spot about two friends taking a walk together, happy to be alive. Vaughan recorded the song on a twelve-string acoustic; it wasn’t released until a year after his 1990 death, however, when his brother, Jimmie, put together a posthumous album, The Sky Is Crying. After a career playing the sturm und drang of electric blues, “Life by the Drop” stood as a pure and simple coda, with Vaughan singing the words written by his faithful friend. “He was very proud of that song,” Logan says of Bramhall, who died in 2011. “It speaks to so many people in so many ways. Songs are like that—that’s something I learned from Doyle. Everybody hears songs in their own way.”

Life by the Drop: Written by Doyle Bramhall and Barbara Logan. Published by Dreamworks Music (BMI)/Wilson Creek Music (ASCAP). All rights administered by BMG Rights Management (US) LLC.

“Lonely Woman” (1959)

In the early fifties Ornette Coleman, who had left Fort Worth for Los Angeles, was in the initial stages of creating a new kind of jazz in which things like rhythm, harmony, and melody were liberated from old rules. But he also had to make a living, which meant stocking shelves at a Bullocks department store. One day on his lunch break, he walked into a nearby art gallery, where he saw a painting that stopped him in his tracks. It was of “a very rich white woman who had absolutely everything that you could desire in life,” he later recalled, “and she had the most solitary expression in the world. I had never been confronted with such solitude.”

That evening, he got to work on a song. Though Coleman’s music had the abandonment of free jazz, his compositions always had a core, a riff or theme that he and the band repeated and improvised upon. The core of “Lonely Woman,” which opened his third album, The Shape of Jazz to Come, was palpably melancholic, from the first bass notes to the slow melody line on saxophone and cornet to Coleman’s bluesy sax solo. The song went on to become a jazz standard, and Coleman never forgot what he felt gazing upon that canvas. As he recalled decades later, “I said, ‘From here on I’m going to support artists no matter what they do—because that artist sent a signal out. That’s not just a painting. It’s a condition.’ I related the condition to myself, wrote this song, and ever since it has grown and grown and grown.”

“The Way” (1998)

In the summer of 1997 Tony Scalzo was living in Austin and writing songs for his band Fastball’s second album. One morning he came across a story in the Austin American-Statesman: “Elderly Salado Couple Missing on a Trip to Nowhere.” Lela and Raymond Howard, both in their eighties, had left home a few days earlier, headed for the Pioneer Day festival in nearby Temple—and disappeared. The story noted that both husband and wife were ailing: she had Alzheimer’s and he was recovering from brain surgery. They had almost certainly met with a terrible fate, but as Scalzo read, he was moved to imagine a romantic alternative. “I was thinking,” he says, “maybe they just wanted to get away from their responsibilities and get back to that time when they were young lovers.”

As this story unfolded in his mind, he began crafting some lyrics, pairing the words with a minor-key melody. At the chorus, he switched to a major chord, to capture the fanciful triumph he imagined for the couple: they had found a way to cheat death and live on.

Less than two weeks later, the Howards were found in their car at the bottom of a 25-foot cliff near Hot Springs, Arkansas. Lost and far from home, they had died the day after leaving Salado. But Scalzo didn’t change his lyrics—he preferred his version of what had happened to them. In 1998 you couldn’t turn on a radio without hearing his song, titled “The Way.” Years later he met the couple’s children. “They were very nice,” he says. “They never made a disparaging comment about this alt-rock guy writing about their family. They were grateful that the Howards got something larger-than-life attached to their legacies.”

Anyone can see the road that they walk on is paved in gold

And it’s always summer, they’ll never get cold

They’ll never get hungry, they’ll never get old and gray.

The Way: Lyrics printed with permission.

“Tom Moore’s Farm” (1930’s)

Tom Moore was a notorious twentieth-century plantation owner along the Brazos River, near Navasota, who ran his land and the mostly African American sharecroppers on it as if it were the nineteenth century instead. In the mid-thirties, a young sharecropper named Yank Thornton, fed up with Moore’s brutal methods—making the laborers toil for long hours in the sun, keeping them in line with threats and violence—began writing verses about him and singing them at local dances: “Standing on the levee with his spurs in his horse’s flank, whip in his hand watching his boys from bank to bank.”

Thornton sang unaccompanied, though a guitarist named Mance Lipscomb—who was a sharecropper on a farm next to Moore’s plantation—helped him shape the verses into an actual song. Lipscomb began playing “Tom Moore’s Farm” too, and his version soon became popular at black gatherings. In 1949 Lightnin’ Hopkins recorded the song, changing the title to “Tim Moore’s Farm” because he was worried about reprisals. His recording went to number thirteen on Billboard’s Most Played Juke Box Race Records. Eleven years later Lipscomb himself recorded it, but he too was nervous about retaliation, so he released the song anonymously. “If he knew I put out a song like that,” he told historian Mack McCormick, “I couldn’t live here no more. I wouldn’t live six months if he knowed that. He got people out there come out here set this house on fire.” In fact, Moore knew all about the song, which, over the course of its life, has existed in at least six versions, by McCormick’s count. “Tom Moore’s Farm” survives today, long after the farm itself was broken up and its subject and writers died.

“L.A. Freeway” (1972)

Los Angeles in 1970 was a mecca for songwriters, and Guy Clark, who was determined to become one of them, moved there from Houston with his girlfriend, Susanna. He didn’t like it. He didn’t like the pollution, he didn’t like their landlord (who chopped down their grapefruit tree one morning), and he didn’t like the fact that publishers were ignoring his songs. But Clark kept at it, and one night, he and his string band landed a gig in a San Diego bar (the doorman was another struggling songwriter, Tom Waits). On the trip back to L.A. after the show, Clark, drunk and tired, began to doze off in the backseat. Suddenly, he started awake and mumbled aloud, “If I could just get off of this L.A. freeway without getting killed or caught.” Clark remembers, “It was like lightbulbs went off. I said to myself, ‘I can’t forget this.’ ”

He knew if he didn’t write down the words before going back to sleep, they’d be lost forever. So he grabbed an old burger bag, asked Susanna for her eyeliner, and scribbled the phrase. Then he tore it off, stuck it in his wallet, and passed out again. Not long afterward, he finally got a publishing deal and he and Susanna moved to Nashville. About a month later, he pulled out his wallet and retrieved the phrase. It was time to start writing the song. As the previous year in L.A. came back to him, the words followed—about the concrete, the landlord, and his stand-up bass player, Dennis Sanchez, a.k.a. “old skinny Dennis, the only one I think I will miss.”

“I didn’t quite know what I had until it was done,” Clark says. Two years later, Jerry Jeff Walker covered the song and made it a hit, and soon everyone in Nashville was recording Clark’s songs.

“Last Kiss” (1961)

Twenty-year-old J. Frank Wilson did not seem destined for rock and roll greatness. Recently discharged from Goodfellow Air Force Base, in San Angelo, Wilson had a steel plate in his head from a childhood accident and a family back home in Lufkin. But he could sing, and when he heard that a local band called the Cavaliers was looking for a new front man, he auditioned, got the job, and decided to stick around town for a while. The Cavaliers played proms, dances, and nightclubs all over the area, and they soon picked up a manager from Midland named Sonley Roush, who set about trying to find them a hit.

Around that time, a song by Wayne Coch-ran, of Barnesville, Georgia, started getting airplay on a radio station in Odessa. A maudlin “splatter platter” reminiscent of 1959’s “Teen Angel,” it had been inspired by the deaths of three teenagers who were killed when their car crashed into a logging truck. Though Roush didn’t much care for the song, teens clearly loved the melodrama of death—week after week, it won the Odessa station’s popularity contest for new releases—and Wilson’s voice was perfect for the pleading vocals: “Well, where oh where can my baby be?” So in 1964 Roush had the Cavaliers record the number exactly as Cochran had done it. The song came out on three different labels, and the third release, on Josie Rec-ords, was the charm, climbing to number five nationally.

That October, as the band was heading to a gig in Canton, Ohio, Roush fell asleep at the wheel and drove head-on into an eighteen-wheeler, killing himself and seriously injuring the others. The deadly crash made the song about a deadly crash an even bigger hit, taking it all the way to number two. Wilson was never able to replicate the success on his own; eventually he returned to Lufkin and took a job as a nursing home orderly, dying of complications from alcoholism at age 49. But the song itself had another resurgence. In 1999 Pearl Jam took it once again to number two on Billboard’s Hot 100, after singer Eddie Vedder discovered a 45 of the song in an antiques store.

“London Homesick Blues” (1973)

When Gary P. Nunn, an Austin bass player and pianist, went to London in 1973 to back fellow Texan Michael Martin Murphey, he stuck out like a cactus on a moor. While Murphey met with the press and went sightseeing with his English wife, Nunn stayed behind in her brother’s Hyde Park flat, sleeping on the couch and watching TV. It wasn’t particularly cozy—the heat came on only at night—but the foreigner had little money and nowhere to go. When he did venture outside, he felt even more alone. Nunn remembers, “I would go out in my boots and cowboy hat that attracted a lot of attention, comments like, ‘Hey, cowboy, where’s your ’orse?’ and ‘Look, it’s John Wayne.’ ” And watching the buskers at the Marble Arch tube station made him homesick for his hippie musician friends.

One day, playing guitar in the flat, he started singing, “Well, it’s cold over here, and I swear, I wish they would turn the heat on.” Nunn hadn’t written much before ( “a couple of cosmic rock and roll things,” he says), but he decided to try his hand at an actual country song. His experiences rolled out, from the local girl who’d stood him up to the limeys eyeing his boots to his longing to be “home with the armadillos” (“the term I applied to the folks in the counterculture scene in Austin,” he explains).

That summer, Nunn was back in Texas, recording the ¡Viva Terlingua! album with Jerry Jeff Walker in front of an audience in Luckenbach. While the tape was rolling, Walker, who had heard Nunn playing his new song earlier in the day, asked him to sing it. The band had never rehearsed “London Homesick Blues,” but they followed along, finishing to rapturous applause. Then, because the sound crew hadn’t caught it all, they played it again, capturing an ineffable moment as well as the lonesome feeling of being far from home. In 1977 the song became the theme to Austin City Limits, setting it up to be one of the most well-known songs about Texas. “It was just an exercise in writing a song,” says Nunn. “I never imagined anything would come of it.”