This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

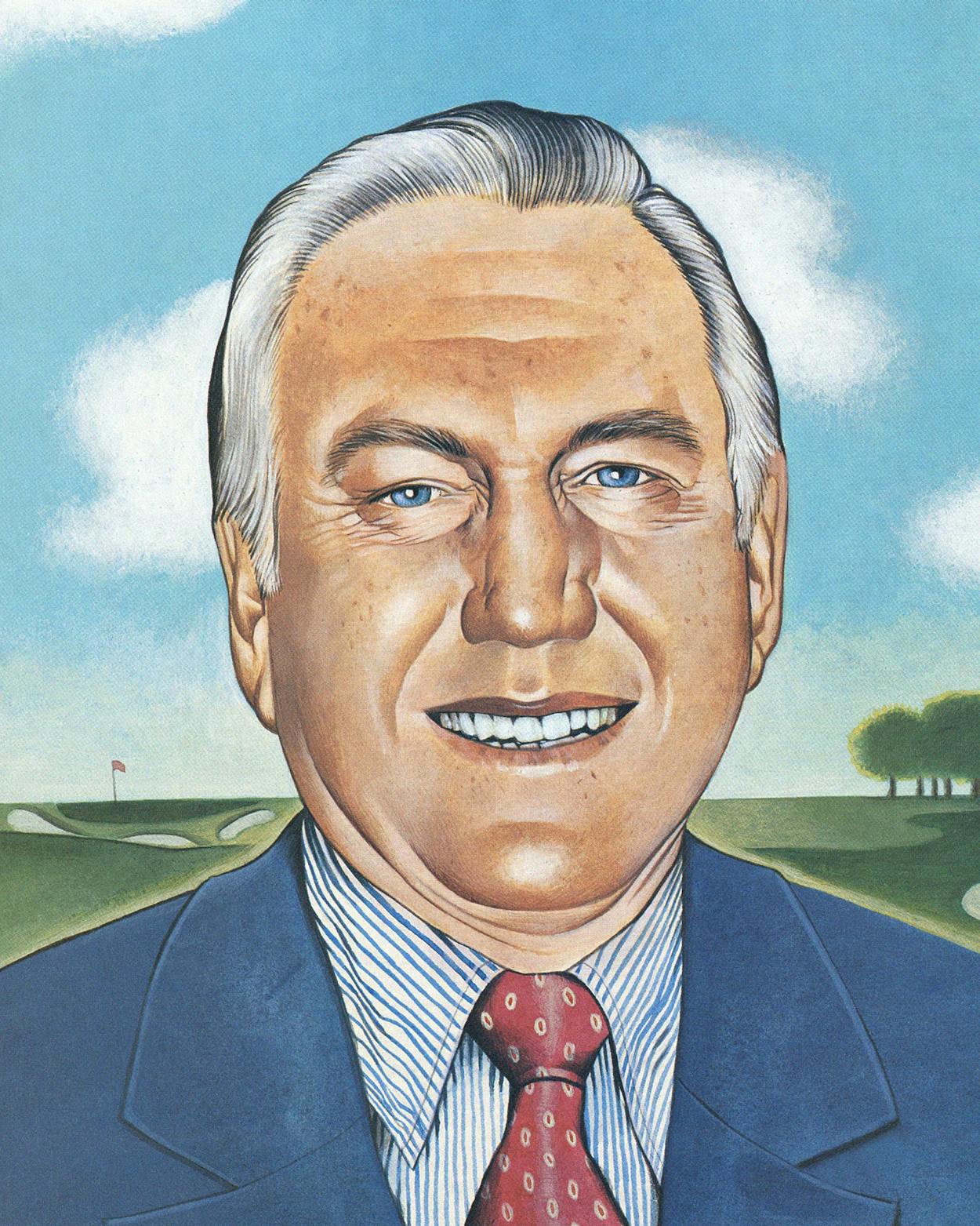

At Robert Dedman’s ClubCorp International offices in Dallas, nothing is more important than time. Visitors are ushered in and out and put in holding patterns like airplanes at DFW. For Dedman, this is business as usual—he has built a life and a fortune from squeezing every minute out of every hour of every day.

“I had an avocation to get rich,” recalls the 67-year-old billionaire, who single-mindedly and relentlessly pursued that goal. Fresh out of high school, Dedman devised a schedule for becoming wealthy. He divided his life into four segments: He would work eighty hours a week until age 35, sixty hours a week until age 50, forty hours a week until age 65, then work part-time or retire. He planned to earn $50 million by the age of 50 and then donate at least $1 million annually to charity.

In Dedman’s private offices, time budgeting is very much on display. Instead of using precious minutes to explain the details of ClubCorp’s birth, he suggests listening to a tape covering that topic. Whenever he strays from the subject to tell an anecdote, he is adept at refocusing the discussion.

In the middle of our interview, I am exiled temporarily to an adjacent closet-size conference room. Photographs of Dedman and his petite wife, Nancy, hang on one wall, an unexpected personal touch in offices otherwise brimming with original art and oriental antiques. There are the Dedmans with George and Barbara Bush and with Gerald Ford and Jackie Gleason. The most striking feature of the tiny room are the three doors, one leading to Dedman’s office, another to his assistant’s, and the third to points unknown.

Bits of conversation drift through Dedman’s open door as he discusses a country club purchase with two visitors—the emergency responsible for my being bumped from the leather chair in front of his desk. In a soft Southern accent, Dedman asks questions, drops Ross Perot’s and Ed Cox’s names, and inquires about the two visitors’ golf handicaps. A group of unexpected arrivals from Arkansas, hoping to chat with a native son, are asked by Dedman’s assistant to return in an hour.

Back in Dedman’s office, I mention the abundance of doors. They, too, turn out to be time-savers, allowing him to move quickly from one meeting to another. Lunch is brought in, a daily ritual Dedman follows to avoid wasting travel time to a restaurant. “It’s fifteen minutes there and another fifteen minutes back,” he explains. As we talk, he is squeezing an exercise ball in one hand, trying to strengthen his grip so his golf shots will go farther; on the fingers of his other hand he counts off his degrees: engineering, economics, and law, all from the University of Texas and all earned while selling real estate and insurance full-time.

Returning to Dallas to practice law, Dedman became a prominent attorney handling such clients as legendary oilman H. L. Hunt. But by his early thirties, Dedman had reached a conclusion. “The only thing better than being a high-priced lawyer is to hire one,” he now says. Slicing his lawyering from eighty to sixty hours weekly, Dedman shifted that time to a new money-making venture. He convinced a developer to give him a deal on 450 acres north of Dallas, on which he promised to build a country club that would raise the value of the developer’s land nearby. Dedman then devoted nights and weekends to founding Brookhaven Country Club.

Club members did not see much of the owner; he continued to practice law for seven years after Brookhaven’s debut. “The management art was forced on me by time limitations,” Dedman says. He credits his ability to pick skilled employees for the growth of Brookhaven into what is now ClubCorp International, the largest owner-operator of private clubs, resorts, public courses, and real estate developments worldwide.

While Dedman’s days are still strictly regimented, he has had to make adjustments to the life plan he made as a youth. Two years past his target date for working half-time, Dedman continues to work sixty-hour weeks, intent on making ClubCorp a $2 billion company before retiring. His first $1 million donation to charity was on schedule, with Southern Methodist University as the recipient. Five years later, he gave the school another $25 million. “I look upon myself as a turtle, methodically plodding along,” says Dedman.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Dallas