This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“My customers aren’t interested in fads,” says Michael Malouf, the proprietor of Modern Toys in Dallas. “What’s cool,” he declares, treating himself to a double scoop of his favorite word, “stays cool.”

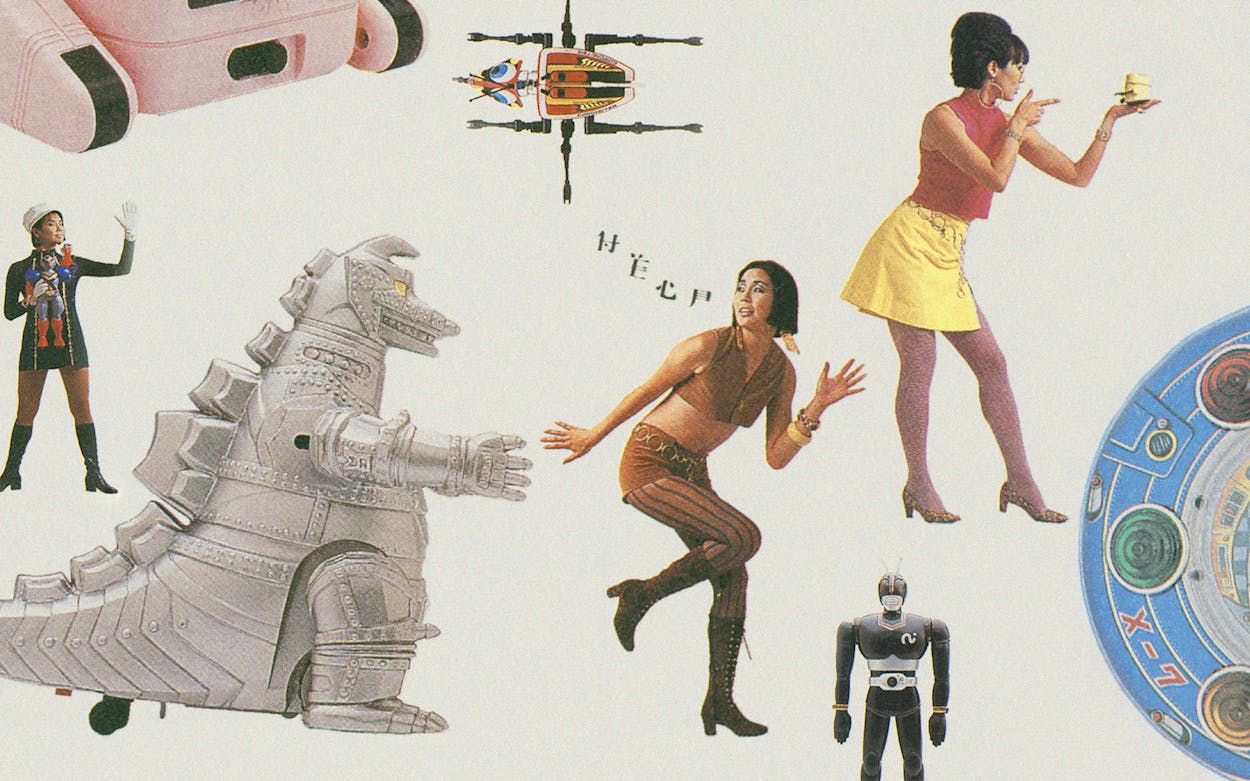

What’s cool to a hard-core group of Japanese-toy collectors around Texas is replicas of characters from the live-action and animated TV adventure shows that have proliferated in Japan since the sixties. The craze really took off in the mid-eighties with a syndicated cartoon series called Macross in Japan and renamed Robotag here. In the sixties kids were spending $10 to $15 to buy metal, plastic, or rubber versions of characters from the shows. Today collectors are already paying three-digit prices for those figures. Devotees even keep abreast of story lines and new products through magazines—in Japanese—and the California-based Animag; many belong to a San Antonio–based club called the Cartoon Fantasy Organization. Foremost among the trends collectors are monitoring is the switch from fanciful warrior protagonists to scantily clad but heavily armed heroines like the Dirty Pair, inspired by a team of female professional wrestlers.

Texas has three centers of the Japanese-toy trade. In Austin Jim Hughes, who like many collectors became infatuated after exposure to the animated videos, sells toys at Atomic City. At Houston’s Third Planet, Kevin Kentner mixes Japanese videotapes, magazines, and collateral toys with an inventory of comic books, sci-fi paperbacks, and Dungeons and Dragons paraphernalia in a scruffy rumpus room of a shop. Meanwhile, on the other side of the spectrum, Modern Toys has shuttered its earnestly trendy pink-and-gray boutique near Highland Park and hied itself—the Zoids, Acumizer, high-tech shelving, and all-over to grand old NorthPark Center. There, Malouf displays his own collection of old die-cast Japanese character toys and a bounteous shrine to Godzilla, who is still going strong in the Orient following a career that has seen him shift from villain to hero and finally back to thoroughly despicable and wildly lucrative villain. Malouf hopes to lure walk-by traffic with an irresistible selection of Japanese toys not made for export. Gleaned from his annual buying trips, they include items from a company that proclaims itself, in ineffably garbled English, “The World’s Leading Creative System Lacking in Individuality of Child.”

Why all the interest in Japanese toys? Malouf credits the Japanese people’s “heightened sensitivity to children” and their special intrafamilial relationships for the extra effort they put into making their playthings. As for the toys’ appeal to Americans, he feels their exuberant graphics and giddy naiveté call to mind the simpler, happier times we like to think we remember from the fifties and sixties. Kentner and Hughes both point to the toys’ ingenuity and—pardon us, Mr. Iacocca—quality of engineering and production. “You just have to look at them next to each other to see that the American toy is a pale rip-off. I’ve got a Japanese character with thirty-six joints,” Kentner says. “I can make him stand on one foot.”

Jerry Jeanmard is a designer from Houston.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- Dallas