This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It is not likely that I will ever be mistaken for a true Texan, even though I have lived nowhere else since the sixth grade. I don’t know how to dance to country music. I haven’t made it past page 47 of the 843-page Pulitzer prize–winning classic Lonesome Dove. On trips to the country, I still find it amusing to roll down my car window and stick my head out in order to moo at cattle.

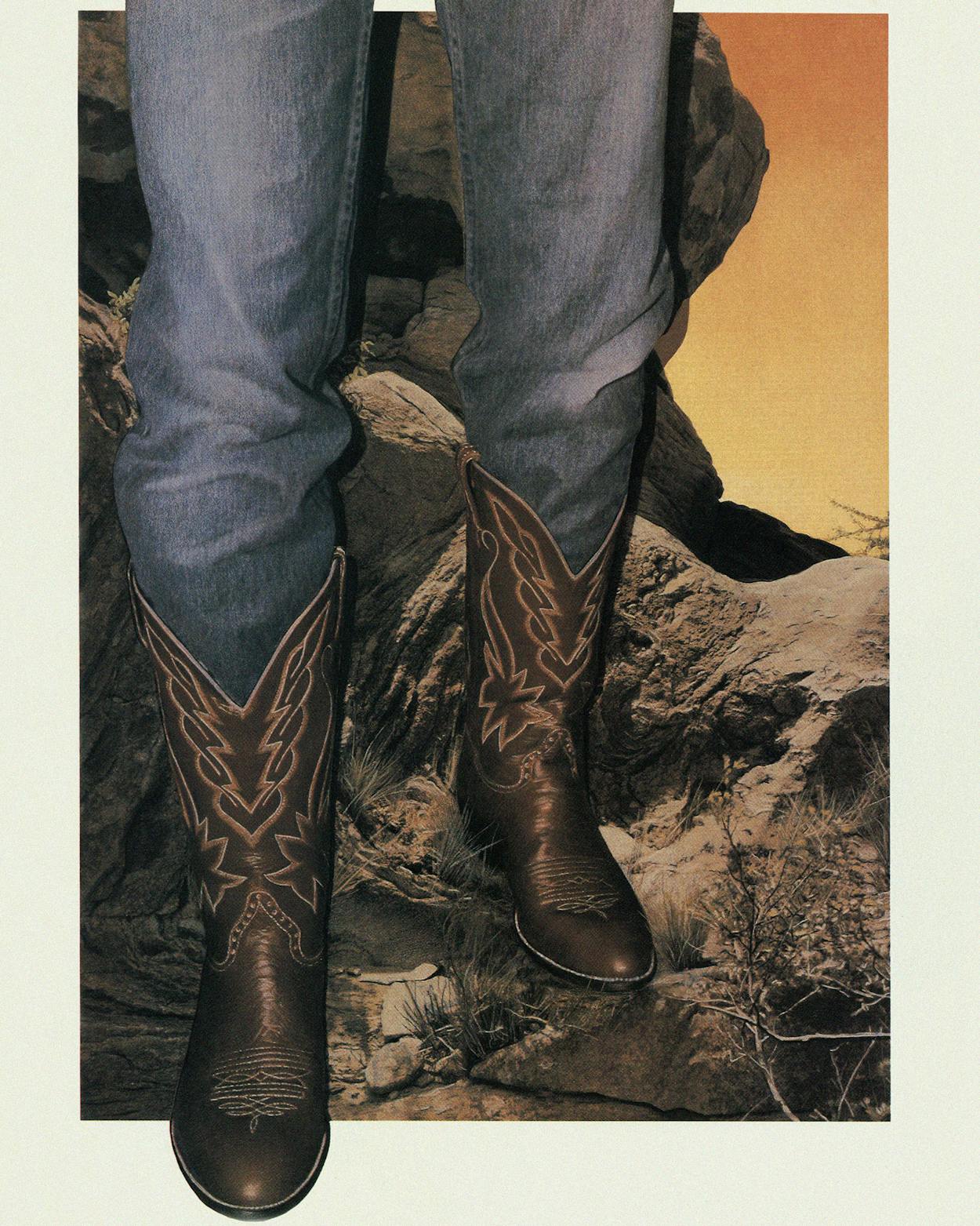

I am what most Texans are these days: an unabashedly urban creature. Accordingly, I cannot explain why a few months ago I began to feel the need to buy a pair of cowboy boots. This should come as no surprise. It is a long-standing tradition in Texas to wear cowboy boots for no practical reason whatsoever. Even so, I must admit I was a little dismayed at myself. I could have sworn that the impulse to look Texan had left me years ago.

I can remember, in fact, the last time I tried. In 1980, after sitting mesmerized through a movie about John Travolta’s attempts to ride a mechanical bull, I stepped out of the theater to announce that my life had been changed. From that day forward, I would embrace my roots, celebrate my frontier heritage. Like the millions of others caught up in the Urban Cowboy movement, I knew what I had to do.

I strolled into Cutter Bill’s, a cavernous store in North Dallas known as the Neiman Marcus of Western wear. I studied the racks of black satin shirts with red scrolls running up and down the front. I pondered the purchase of a big brown cowboy belt with my name—SKIP—hand-tooled ruggedly into the leather. I tried on a cowboy hat the size of an open umbrella.

A young salesclerk with Reba McEntire hair slid up beside me and put a beer in my hand. “Howdy,” she purred. Four beers later, after telling this dazzling woman that I used to do a little high school rodeo, I was looking at myself in a pair of orange ostrich boots. I felt like I was on stilts. I took two steps and almost tilted over.

“Now, that’s good-looking,” cooed the saleswoman, well trained in stifling her laughter. “The high angular heel, you know, will kick easily into your stirrup.”

I bought the boots for $360, the most I have ever spent and have sworn to myself I will ever spend on footwear. They went straight to my closet, to sit amid old unpolished shoes and fallen coat hangers. Too embarrassed to wear them, I also felt too guilty to give them away, as if giving up on them would mean I was giving up on my own Texistential state of mind, on the image of myself—SKIP—as the heroic individual, out conquering the West.

Luckily, Urban Cowboy went bust, Cutter Bill’s closed (its owner, the legendary Rex Cauble, was convicted of drug racketeering), and other people began keeping their boots in their closets. I didn’t feel so bad. I could be a city boy again. I wore my loafers with joy.

And then I heard boots were back.

Last year, while perusing some back issues of Tack ‘n Togs, which I’m certain you know is the magazine of the Western-wear industry, I read the following: “Western boots are mainstream! They’re accepted! They’ve come uptown. . . . Young urbanites are spurring Western boot sales to heights not seen since the dizzying ride with the Urban Cowboy.”

No, I thought, not again. I called Maria Romano, an editor at Elle, an influential New York fashion magazine. She told me she owns four pairs of cowboy boots and two pairs of shoe boots (a modified cowboy boot cut off at the ankle). “Oh, come on. Everyone is getting a couple of pairs of cowboy boots,” she said in that exasperated tone of voice all fashion writers use when speaking to commoners. “We’ll put cowboy boots in our fashion layouts with anything—dressy clothes to casual wear.”

I should have seen it coming. For the last couple of years, while fashion spreads in Texas magazines were featuring the latest in New York and European designs, fashion features in New York magazines were busily promoting Western styles. And it wasn’t just Ralph Lauren doing that rich-rancher look with patchwork blanket coats. Here came Europeans Jean-Paul Gaultier and Georges Marciano, not exactly experts on cowboy chic, sticking their models in old blue jeans and denim shirts. Alexander Julian, known for his dapper metropolitan look, produced a perplexing magazine ad in which his models donned cowboy hats and reclined on animal skins. Guess even made a pearl-buttoned see-through Western shirt for women.

And everybody in this new buckaroo fashion world was wearing cowboy boots. In 1982, the year of the original Urban Cowboy zenith, nearly 17 million pairs of boots were made. That dropped to 8 million by 1985. But by 1990, sales had bounced back: Americans bought more than 12 million pairs.

Now there are clunky Guess shoe boots and low-heeled cowboy boots by such elite shoe manufacturers as Kenneth Cole. There are cowboy boots covered with fringe and made of soft, scrunched-up leather that falls down like bad socks on the sides. There are shiny gold lamé cowboy boots that look like something out of a Vegas act. There are cowboy boots that look more like Harley-Davidson motorcycle boots, with metal toe clips and chains wrapped around the shank. Laredo Boots has introduced 74 styles of boots for women, in colors from hot pink to red with black polka dots.

Even the famous El Paso boot manufacturers—creators of the powerful, dark, exotic-skinned boots worn by Texas’ Petroleum Club crowd—are adding a variety of styles, including caribou, sea bass, kangaroo, and a black and white calfskin print. The great Tony Lama company, renowned for its tough high-topped cowboy boots, introduced a new line—Creations by Lama—featuring boots in French calfskin and Italian leathers and some kind of hairy fake-zebra thing that Rod Stewart once wore on a rock tour.

“Who is buying this stuff?” I wondered, leafing through my precious copies of Tack ‘n Togs. Obviously the cowboy boot, the one thing that Texans could always rely on to distinguish themselves, had moved on to become an icon of other cultures.

It was time for a fact-finding mission. I decided to visit that new mecca of the cowboy boot, the place that now reveres the boot the way the ancient Romans once revered the winged feet of Mercury. I headed, of course, for Los Angeles.

You’re at the right spot,” said Stacey Robinson, the obligatory blond concierge who greeted me at my L.A. hotel. “I have six pairs of boots. In college I was totally known for wearing miniskirts with cowboy boots.”

Though an estimated 40 percent of boot sales are in the oil-patch states of Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana, the greatest growth in boot sales is now on the East and West coasts. “It’s amazing the sea change that has taken place,” Tack ’n Togs editor Daniel Deweese told me. “It’s hard to imagine that Los Angeles would ever get close to Dallas in boot sales, but that’s what’s happening.”

Indeed, in L.A. there are billboards advertising a chain of ten Western wear stores called the Thieves Market. One billboard showing an array of Justin boots reads, MORE SNAKES THAN A HOLLYWOOD PARTY. Melrose Avenue, the hippest shopping district in Los Angeles and one of the most fashionable streets in the world, looked like a cowboy boot outlet center. Shops selling new cowboy boots were next to shops selling used ones. The voguest shoe stores on the street featured cowboy boots in their windows and were charging up to $200 more for boots than a Texas store would. In natty Italian suits, salesmen pulled out Justins and Noconas before contemplative customers and discussed such details as “full-quill vamps.”

Though the most popular boots in Texas, like those made with black iguana skins, were also popular on Melrose, I could tell there was something strange about the boots here. They all had elongated, pointy toes, the kind that Texans scornfully call roach killers. But evidently that was the style the Melrose crowd wanted. I couldn’t find in any of the stores the traditional Texas man’s boot—the Roper, the low-topped, wide-toed boot named for the calf ropers who work in them. “Oh, God. You mean that shitkicker boot,” said the charming Miss Romano of Elle. “Come on, that’s only a Texas thing. No one else wants that.”

If the original Urban Cowboy movement was aimed at middle America, then the Son of Urban Cowboy was striking at America’s terminally cool. In a sort of Madonna-goes-to-Lubbock look, women wore spandex aerobics shorts and colorful cowboy boots. Men wore ponytails, black jackets, old T-shirts, stonewashed jeans, and black cowboy boots. Here came a spike-haired guy wearing a T-shirt that read “Anarchy!” hurrying down the street in green lizard boots with silver spurs—spurs!—that scraped the concrete.

One of the most popular Melrose haunts was a cowboy boot store owned by a thirty-year-old man named Mark Fox. It was difficult for me to believe that the bearded Fox, with his brown hair falling below his shoulders, a brown leather jacket hanging off of his thin body, and his black motorcycle parked in front of the store, could be considered an expert on cowboy boots. But here, everyone seemed to know him in the way Texans once knew the name of Sam Lucchese. “Hey, Mark, baby!” people called out. “Oh, this is nothing,” Fox told me, a look of studied insouciance on his face. “You should see how they know me in Europe.”

Fox’s specialty is vintage boots—wildly colored boots made in the thirties, forties, and fifties and popularized by such cowboy movie stars as Tom Mix and Roy Rogers. Fox obtains these ancient hand-tooled boots from collectors all over the country. If he finds a good pair, he charges up to $650 for them.

“My store is the place to be,” Fox said. “A lot of stars have to drop by to see what I’ve got.” Right on cue, in black cowboy boots, in walked Carré Otis, a model and actress known mostly for her sultry scenes in Wild Orchid, a movie with Mickey Rourke.

“I already own seven pairs of cowboy boots, but I’m always looking,” she said, lighting a cigarette and giving me the once-over. I was wearing Nikes. “You said you’re from Texas? You should get some boots. They give you attitude.”

Attitude? People in Los Angeles, I realized, might own bolo ties and silver-buckled Western belts, but they aren’t cowboy wannabees. They care nothing for extra-long jeans that don’t ride up on their legs while in the saddle. They want to stuff their jeans inside their boots so the boots can be seen. For them, boots are a primary fashion statement—a sign of the right attitude. When the original Urban Cowboy movement, based on the styles seen at Texas country and western bars like Gilley’s, failed—it lasted about three years before crashing in 1982—companies that were overstocked with gaudy Western apparel held fire sales and swore they would never get in that business again. The Western look, they said, was dead. But, as we should have all learned long ago, nothing is ever dead in fashion; it usually resurfaces a few years later as a brilliant innovation.

In 1983 a handsome Frenchman named Robert Rapin bought thirty pairs of black cowboy boots for next to nothing in Dallas, took them to Paris, and sold them all within a week. He opened a Western wear store on the Right Bank called Cowboy Dreams and put up a sign that read, “Un Coin de Texas à Paris” (“A Little Bit of Texas in Paris”).

“In the mind of the Frenchman,” Rapin told me in his heavy accent, “this old cowboy image was appealing. Frenchmen loved old black and white western movies. They loved this old American look. And they wanted my bee-yoots!”

“Excuse me?” I asked.

“My bee-yoots. My cowboy bee-yoots.”

The old movies always showed cowboys wearing pointy-toed boots. The French—the same group of people who consider Jerry Lewis one of the great movie actors of all time—were captivated. Their rage for black clothing also made the black cowboy boot a prize.

Soon other Western stores popped up in Paris. “Believe me, my friend, you can find better Western apparel there than in Dallas,” said Rapin, who now spends most of his time in his Dallas warehouse shipping custom-made boots to France (a black lizard boot that costs $195 in a Dallas store will cost $300 at Cowboy Dreams). By the mid-eighties, European designers such as Georges Marciano were creating a jeans-and-cowboy-boot look. American models who went to Paris began coming home wearing black cowboy boots. Inevitably, by the late eighties, the pointed cowboy boot, abandoned decades ago by the Western market, was becoming the newest twist in America’s trendiest fashion circles.

“I have never understood the logic of it all,” said John McAlpine, the director of product development for the prominent Tennessee boot company Laredo Boots, “but it was the Europeans who made us love the cowboy boot again. Guys in New York and Los Angeles who thought cowboy boots were redneck suddenly saw them in Paris and decided that they were great. If the Europeans were wearing cowboy boots, then to us they had to be authentic.”

When one of America’s greatest cultural influences—the heavy-metal band—began to swear by cowboy boots, there was no turning back. Mötley Crüe, Guns N’ Roses, Bon Jovi: All the band members were wearing vividly colored cowboy boots covered with chains and buckles and metal strips. “We weren’t naive,” said McAlpine. “We knew urban American kids were no longer thinking about a video when they were buying boots. They were thinking about those fine folk who have long hair and lots of tattoos.”

Meanwhile, out of touch with the popular currents, Texans kept wearing their sober, rounder-toed boots. Major boot manufacturers began making one line of regular high-heeled rounder-toed boots for the conventional boot wearer and another line of lower-heeled pointy-toed boots for customers on the coasts.

“Everybody out here is trying for an outlaw look,” Mark Fox told me. “Like an American renegade appearance, you know? Old ripped jeans, a fifties leather jacket, and cowboy boots that look good on the pedals of our Harleys.” He paused and glared at me. “You don’t understand what I’m saying, do you?”

I had to admit that I did not. Toward the end of my day on Melrose, the harsh light of the sun washing out any sense of time or place, I had the sinking feeling that I was fitting into the Euro-Western attitude about as well as I had with the Urban Cowboy. Nevertheless, as someone who feels obligated to be in on all trends, I gave Melrose one last chance. I saw a store called Texas Soul. A huge map of Texas with a sculptured cowboy boot sticking out of it had been placed above the front door. I walked in.

Rock music roared out of stereo speakers, bounced off the three thousand pairs of boots, and hit me like a boxer’s punch. A customer near me in a black leather vest and pants grabbed a pair of blue boots and said, “Dudical” (an apparent combination of the two popular Southern California words “dude” and “radical”). Farther down, three rather startled Japanese tourists listened to a young man with long curly hair, who was wearing black boots, black jeans, and a black T-shirt. “Listen, guys,” he said. “Our big seller is the Nocona pointy toe at one hundred and ninety-five dollars, all black. It’s a bitchin’ boot.”

What was this, I thought, boot purgatory? After a few minutes, I worked up the courage to introduce myself to the salesman. “You’re from Dallas?” he asked. “All right! I grew up in Richardson! I moved out here with my heavy-metal band. We used to be called Sin City, but now we’re called Danger.” He gave me a puzzled glance. “Man, you’re from Texas, and you don’t have boots? Let me show you our black . . .”

Suddenly it was time to go. I felt sillier here than I ever had a decade ago at Cutter Bill’s. “Maybe next time,” I said.

“Well, listen, man, you ought to get a pair,” he said, shaking his hair out of his eyes. “Always remember, boots are like rock and roll. They’ll never die.”

A few weeks later, safe at home among the highways and glass skyscrapers of North Dallas, I drove past a place called Boot Town. Despite the attention now given to L.A., there are still plenty of places to get boots in Dallas. Sheplers and Cavender’s and Western Warehouses are everywhere. In the Dallas Yellow Pages, I counted 45 stores that sell boots.

I thought for a moment, then turned my car around. On sale by the front door were drinking glasses shaped like cowboy boots. Huge silver belt buckles, the size of soap dishes, were displayed in a glass case. A couple of salesmen in big white cowboy hats were hanging around next to the counter, their bellies pushing out, their hands plunged into their front pockets. “Howdy. Where y’all from?” they asked everyone who dropped by.

I slipped to the back, past racks of Western shirts and Wrangler jeans and Resistol hats, past the ladies’ fringed dresses and colorful square-dance skirts. In the men’s boot section, I found no red or purple boots, no boots with fringe or zebra stripes. Instead, there was the usual array of Texas-made Tony Lamas, Luccheses, Noconas, and Justins. I did see a couple of pairs of black pointy-toed boots with silver tips, but as I started to examine them, a female voice behind me asked, “You really like those? They’re usually bought by the fruity types.”

I turned around to be greeted by a saleswoman, Sandy Cooper, a native West Texan with thick blond hair and a thicker drawl. She was wearing real cowgirl clothes: a striped Panhandle Slim shirt, an old-fashioned pair of “chap jeans” (blue jeans that have denim chaps sewn into the legs), and a new kind of cowboy boot that California hasn’t seen yet, the lace-up Roper, a cross between a cowboy boot and a logger’s boot that has become highly popular among working cowboys in rural Texas.

I told myself not to discuss boots with her. “I’m just here to look,” I said.

“Look all you want,” she replied, giving me the kind of small-town rodeo-queen smile that can make a city boy weak. “But just in case, let me show you one thing that looks good on a Texas guy.”

A Texas guy, she said. She saw me as a Texas guy. Me—SKIP—the rugged individual. Out conquering the West. A man’s man. A man, at least, who does not shop on Melrose Avenue.

My eyes blinked quickly behind my horn-rimmed glasses. “Why, thank you,” I said. Fifteen minutes later, I was headed out the door with a sturdy round-toed pair of elk-skin boots. They looked like something a brawny truck driver would wear. They cost me $180, and I didn’t feel the slightest twinge of guilt. That night I proudly wore them into a restaurant. “You’ve got to be kidding,” said an incredulous friend of mine. “You bought some boots? You? What got into you?”

It might be silly to believe that a new pair of boots is going to make me more of a real Texas man. But I also know that to deny myself a pair is to admit that the myth is no longer worth chasing. And that’s something I cannot yet do.

“Hey, you should get some,” I told my friend. “They give you attitude.”

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fashion

- Cowboy Boots

- Dallas