This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The leggy runway models with their elegant, slicked-back coiffures milled frantically backstage among the racks of clothes and tables piled high with handbags, scarves, and belts. The only person who seemed capable of imposing order on this chaos was the fashion consultant from New York, who was getting paid more than the average secretary makes in a year for staging this single gala presentation of Dallas-designed fashions. Outside, in the grand ballroom of the Adolphus Hotel, a thousand guests, well lubricated from a week-long round of preparatory cocktail parties, sat behind their $12.50-a-plate dinners and awaited the event that would establish Dallas as a design center to one day rival New York. The evening’s special guests were 45 of America’s most prestigious fashion editors, headed by the New York Times‘s Virginia Pope and including the editors of Vogue, Charm, Glamour, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Women’s Wear Daily. There was a serious problem with the service: the waiters drank most of the champagne and five policemen had to be called to restore order in the kitchen. But the eleven-scene fashion show—highlighted by a Texas Roundup sequence that was greeted with whoops and whistles—went off flawlessly. And when the show was finished, designer Mary Greenburg of the Lorch Manufacturing Company was awarded the first-ever Dallas Alice, the local design Oscar that would announce the commitment of one of the nation’s largest apparel manufacturing centers to creative excellence. Greenburg’s winning design—a sleeveless, just-below-the-knee, white waffle-piqué dress—was described as “crisp in line and smart in its simplicity.”

The prestigious fashion editors were polite but restrained in their enthusiasm—Dallas’s children’s-wear designs received most of their kudos. A year or so later one of them came back to speak to the Dallas Fashion Group and the Dallas Fashion and Sportswear Center, the sponsors of the Alice award. Frances Harrington, editor of Charm magazine, made some general remarks about the state of women’s fashion. “You are famous for your casual clothes,” said Harrington, “but I wish the Dallas market would make more noise, that it would attract the conspicuous attention that it deserves.” She suggested a more diversified approach to design and fabric selection. She also let it drop that blue would be the color for the season that everyone was then preparing for: spring 1949.

“Dallas designers are still announcing their imminent arrival, and everyone is still waiting for them to make some noise. This year has seen the latest renascence of the Dallas designer, with new directions, new hopes, and a new media barrage.”

One hundred sixty-seven fashion seasons have passed since that blue-keyed spring, and in many ways the status of the Dallas fashion designers has changed little. Though they now ply their trade in an even more important center of apparel production and distribution—surpassed only by New York and equaled only by Los Angeles—they are still announcing their imminent arrival, and everyone is still waiting for them to make some noise. This year has seen the latest renascence of the Dallas designer, with new directions, new hopes, and a new media barrage. (Unfortunately, the Dallas Alice is no longer around to highlight the occasion.) If this does indeed mark the turning of a corner, it will be not only because of the emergence of a number of talented young designers but also because of fundamental changes in the world of fashion. The designer ready-to-wear explosion of the seventies sparked the rise of American designers and signaled the end of the Paris couturiers’ style-setting hegemony, while the working women of America’s baby-boom generation emerged as powerful tastemakers. As a consequence, the geographical hierarchies of fashion, although still powerful, are no longer inviolable. Regional design centers are no longer impossible, and are perhaps inevitable.

To find out what is possible in the design capital of middle America, I looked at several Dallas designers who represent an aesthetic and economic cross section of the city’s apparel future. The designers range from Polly Ellerman, vice president for design at Prophecy, a $30-million-a-year line of women’s sportswear, to Todd Oldham, a young innovator struggling to make it on his own. What they all have in common is a reputation for bringing excitement and originality to their designs and a determination to succeed where so many before them have failed.

Fashion design is clearly an art, but an art more akin to architecture or filmmaking than to a more private medium like painting. It is the world’s most widely consumed art form, and the scale and expense of production are as considerable as the potential revenues. But whether he or she is a Paris couturier or an engineer of budget shifts, a designer needs a paying audience. Without customers, a designer is not simply a painter without patrons but a painter without a canvas.

It was customers who brought fashion to Dallas. By 1850 the city was known as the world’s greatest market for buffalo hides, and the conjunction of two railroads a few years later brought in a plethora of peddlers. (We know them now as sales representatives.) Word was out: if you wanted to sell something in Texas, you sold it through Dallas, the distribution center of the Southwest. In 1888 a 27-year-old foot peddler named August Lorch came to Dallas to sell dry goods and shoestrings, and in 1892 he was doing well enough to become a one-horse peddler; the next year he got a second horse. Two years after that he started the Lorch Dry Goods Store in Midlothian, and by 1909 he had opened a two-story warehouse to wholesale women’s apparel to the 400 retailers attending the annual Spring Merchants’ Meeting. That was the beginning of the local wholesale apparel distribution business, which now draws 100,000 buyers a year to the mammoth Dallas Apparel Mart.

Lorch started manufacturing dresses in 1924 in a factory on Jackson Street, but he was edged out for the distinction of being Dallas’s first apparel manufacturer by the partnership of Higginbotham, Bailey, and Logan, which set up a plant to manufacture men’s work clothes in 1919 and branched out into a line of Virginia Hart “wash dresses” two years later. Other firms slowly came into the manufacturing business, and by the late thirties Dallas already had a modest reputation as a producer of sportswear—the blouses, skirts, jackets, and slacks that bridged the gap between cheap workaday housedresses and Sunday finery and that were starting to catch on with a less formal American woman.

But it was the war that really got the Dallas apparel industry going. The European fashion centers closed down, transportation from the East Coast was unreliable, and Rosie the Riveter needed practical clothes to wear to her wartime job. So women started buying casual clothes that were made closer to home, and they didn’t need to worry about how those clothes might stack up against the latest mandates from Paris. Of course, when the Paris couturiers had their first show in the newly liberated city, in November 1944, Dallas’s most fashionable stores—Neiman-Marcus and A. Harris—got immediate shipments of designer clothes, and Titche-Goettinger sent its fashion director to New York to read the cabled notes on the show and to commission its own interpretation of trends like Lanvin’s top-heavy look.

Because of the war, Dallas’s manufacturing base expanded to seventy or eighty firms that made everything from uniforms to hats to silk underwear. The Dallas firms tried to escape their sportswear stereotype with elegant dress designs and a few imported designers, but the real action remained in sportswear, led by the Lorch Company and a former Higginbotham, Bailey, and Logan shipping clerk named Justin McCarty, who had established his own company in 1927. Sportswear was a natural for the suburban lifestyle that was sweeping the country, and it also offered flexibility to an increasingly important buyer, the working woman. By 1952 one third of America’s women were working, and those women were buying 50 per cent of all ready-to-wear clothing sold in this country.

During the fifties, Dallas also took the lead in introducing new fabrics. Even before the invention of the sewing machine and the advent of mass manufacturing of garments, wool had been the only material suitable for proper clothing. Fashions were dictated—both in the United States and in Europe—in northern climates where wool was essential for warmth. Cottons were limited to the most informal wear, particularly dresses for women slaving in hot, steamy kitchens and laundry rooms. But with the widespread adoption of central heat in America’s postwar suburbs and office buildings, cotton became practical, and the Dallas designers started doing dressier sportswear in that once-déclassé fiber. The Dallas manufacturers were also among the first to recognize the utility of the synthetic “miracle fibers” that had been developed out of wartime research; what could be better than casual clothes that didn’t wrinkle?

The fifties were the halcyon years of the Dallas industry, which included nearly two hundred manufacturers by the end of the decade. Although Stanley Marcus might occasionally chide the locals for their adaptive rather than innovative design sensibility, the best Dallas firms—like Lorch and Justin McCarty—had a flair for tasteful, updated versions of by-now-traditional sportswear. They used the miracle fibers judiciously—mainly in blends—and they made extensive use of a good variety of natural-fiber fabrics in their better clothes. They kept up with the working woman—Justin McCarty prophetically urged her to “go to blazers” in 1959—and were in many ways already at the point at which today’s most advanced Dallas manufacturers have recently, and with much fanfare, arrived.

During the sixties things changed. The local boys looked around and saw that they were an industry—with the third-largest payroll in Dallas—and they started acting like one. Firms started building state-of-the-art factories, and synthetic fibers began to dominate local manufacturing. Chain stores like J. C. Penney and Sears, Roebuck & Company became important patrons of manufacturers who cranked out budget- and moderate-priced garments that featured easy care, durability, and safe, predictable styling. A classic success story of the era was Fame Fashions, which opened in 1962 and took its first design, an utterly plain, belted, short-sleeved, knee-length dress, to T. E. Beach, the manager of Penney’s Irving store. Beach liked the dress so much that he and buyers from other Penney’s stores eventually ordered a million dollars’ worth, and the Fame factory did nothing but produce that single dress for six months.

Even Trammell Crow’s Apparel Mart, which opened in 1964 and offered a much larger and more sophisticated arena for wholesale distribution, became a double-edged sword for local designers. It gave the Dallas industry a heightened visibility, but what quickly became visible was a marketing stereotype that is still hard to shake: synthetic fabrics, low prices, and safe-to-boring styling. In industry parlance, Dallas became known as a producer of “dumb” clothes. The chemical-fiber industry loved it, though, and the great hall of the Apparel Mart seemed to be the stage for celebrating every synthetic fiber that hit the market. If you didn’t pay close attention, you could get the idea that Trevira and Qiana were Dallas’s leading designers.

Meanwhile, the world of fashion was shaken by a series of earthquakes. By the mid-sixties the English mod look had severely damaged Paris’s reputation as the trend-setter. Paris was also sowing the seeds of its own destruction in the form of Yves St. Laurent, who in 1966 started producing a ready-to-wear collection to be marketed from his string of Rive Gauche boutiques. For a brilliant young couturier like St. Laurent (who first visited America in 1959 to pick up an award from Stanley Marcus in Dallas) to market a ready-to-wear line was the shockingly vulgar, commercial sort of thing that one might expect of, well, the Americans—an observation that was not lost on American designers.

“For a brilliant young couturier like Yves St. Laurent (who first visited America in 1959 to pick up an award from Stanley Marcus in Dallas) to market a ready-to-wear line was the shockingly vulgar, commercial sort of thing that one might expect of, well, the Americans—an observation that was not lost on American designers.”

In 1971 St. Laurent further dismayed traditionalists by barring the press from his couture show because he didn’t want it detracting from the luster of his prized ready-to-wear line. Shown that kind of respect, Rive Gauche took off, and such leading European designers as Valentino followed with their own ready-to-wear lines and boutiques. But it was American designers like Halston and Bill Blass—who had never excelled at dramatically costuming runway models but had some clever ideas about how to dress real people—who really cashed in on designer ready-to-wear. The French had established that it was no longer vulgar to sell lots of clothes, but when it came to selling lots of anything, nobody did it better than the Americans.

The designer ready-to-wear boom of the seventies cast the Dallas designers in a curious paradox. The world of fashion was going in their direction, toward lower-priced, practically constructed, more casual clothes that didn’t have to trace their stylistic antecedents to Paris. The Dallas designers were viewed even more disparagingly as their New York colleagues climbed to fame. When American design leadership had appeared unattainable, Dallas’s stodginess had seemed acceptable, but now that Seventh Avenue had proved how good America could be, Dallas’s lack of creative ambition seemed all the more reprehensible. Not that the cash registers stopped ringing, however; Stockton Manufacturing Company, which did a big chain store business, reached $60 million a year in sales volume by the end of the decade. Figures like that merely reinforced the notion that Dallas specialized in dumb clothes. Dallas grew up as a city during the seventies, and the industry continued to grow with it, but its designers seemed—though perhaps deceptively—to be farther from the center than ever before.

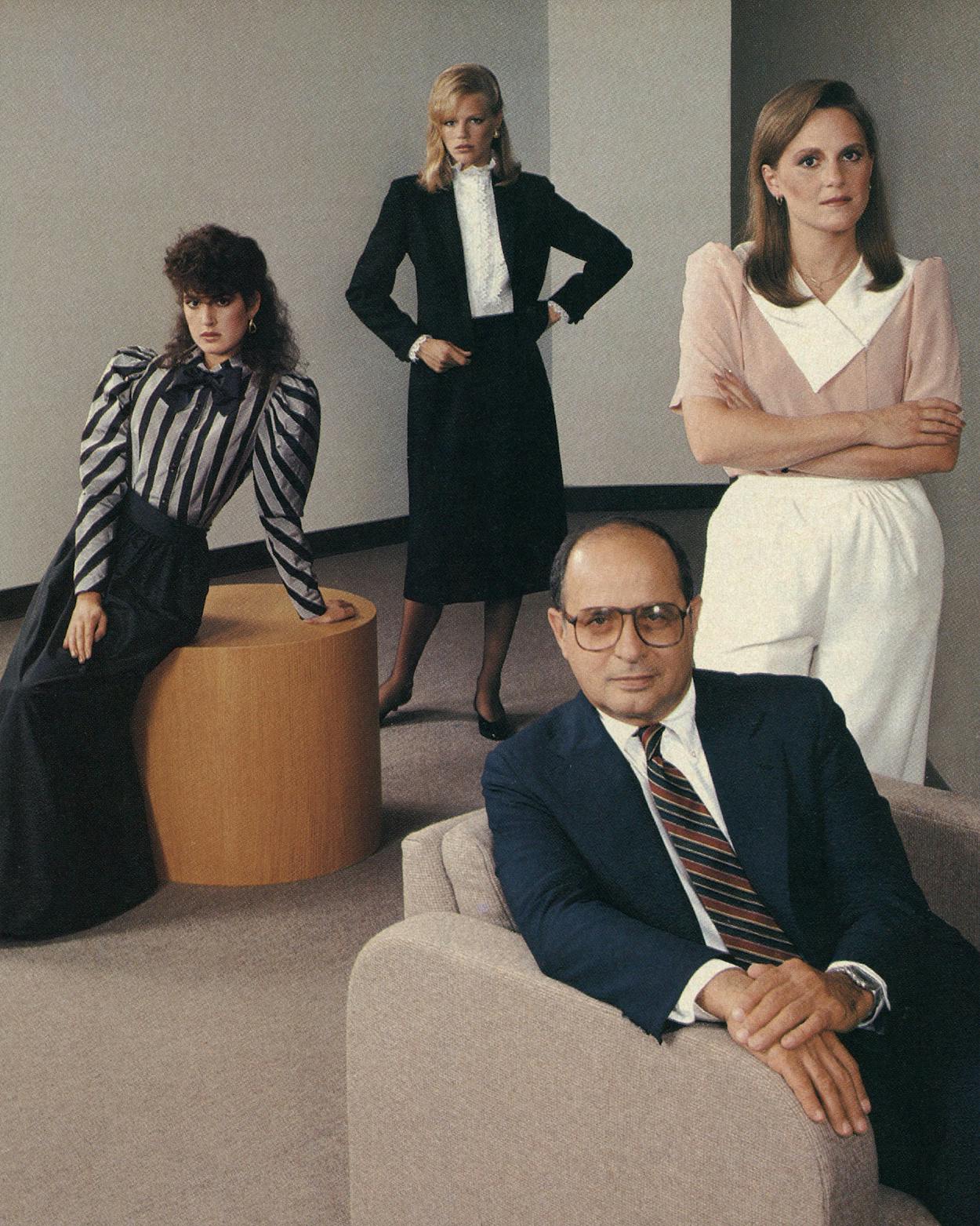

Prophecy began life in those doleful seventies, and its success is due both to overcoming and to working within the stereotypes of the Dallas apparel industry. Prophecy has all the trappings of industrial grandeur that characterize the Dallas apparel trade. From the second floor of the company’s headquarters and massive factory in an industrial park in Carrollton, just north of Dallas, Prophecy president and founder Carl Abady can look through his office miniblinds at newly poured six-lane avenues lined with warehouses and talk about one day being as big as Levi Strauss. It is not an entirely disproportionate boast; in the cavernous warehouses behind him and in Prophecy’s three other Texas factories, hundreds of people already draw, cut, sew, and market a million pieces of women’s sportswear—worth $30 million in sales—a year. But Prophecy is also, at least in the view of many observers, one of only two or three major manufacturers in Dallas that have successfully bucked the dumb image, and Prophecy designer Polly Ellerman is one of a handful of Dallas fashion-house designers to establish her own subtle imprimatur.

As is the case with all major manufacturers, design at Prophecy is a team effort. The team leader is clearly Abady, an ebullient, balding man who wears bifocals with fashionable tortoiseshell frames and who loves to throw out marketing aphorisms. Abady begins the design process by deciding who his customer is, a concept without which a design team is as aimless as an athletic club that doesn’t know what sport it’s playing. Fortunately, Abady has spent his entire thirty-year career watching his customer grow up, and he knows quite well who she is.

Abady grew up in Cleveland, studied economics in college, and got into the apparel business after the Korean War because that’s what his brother was doing. He spent four years in sales out of St. Louis, working for Lampl Fashions, one of the sprightlier manufacturers of dresses and sportswear of the Eisenhower era. One day in 1959 his boss asked him if he “wanted to play in the major leagues,” which from the perspective of St. Louis meant moving to Dallas.

At the time, perhaps the most important customer in the history of fashion was making her entrance. She was the postwar baby-boomer, who was entering her teens, outgrowing her pinafores and jumpers, and beginning to define her own youth culture. She was known to the apparel industry as a junior, and junior clothes had always been a small but not insignificant portion of the post-World War II industry. But the arrival of that demographic bulge meant a decade-long windfall for the firms that geared up for it, and Lampl was one of them.

Abady moved out of sales and into management, and in 1969 he was recruited back to St. Louis to help run another large manufacturer, Thermo-Jac. Two years later, when Abady was squeezed out after a dispute with the company’s head designer, he decided to start his own business in Dallas. He found two partners—Barry Miller, a New Yorker whose father had been in the apparel manufacturing business, and Luigi Mungioli, an Italian pattern maker with a European eye for fit and tailoring and plenty of technical know-how.

Abady considered his principal skills to lie in marketing and “product direction,” and by the time Prophecy opened in 1971, he had already decided on that direction. His marketing epiphany came via a Sanger Harris merchandising manager named Bill Lynch, who pointed out that the all-important demographic bulge had passed the junior phase. The baby-boom woman was ready for clothes that would express her independence in a liberalized society. That look would come to be known as contemporary.

Prophecy did not immediately conquer the contemporary market; it started off with dresses that it marketed to J. C. Penney, which was by now so enamored of dumb Dallas designs that it had established a regional buying office there, joining Sears and Montgomery Ward. At first Prophecy’s dresses had the top a different color from the bottom, to get the sportswear look, but by 1973 it was making those pieces separately and had created a full-fledged contemporary sportswear line.

The contemporary look blew into the market very quickly, thanks to a number of new small specialty stores that were likely to be owned or operated by women who were themselves contemporary. It peaked about the time that Polly Ellerman came to interview at Prophecy in 1974. She had graduated from Washington University in St. Louis with a degree in fine arts, and intent on a career as a designer, she decided that she would rather live in Dallas than in New York or Los Angeles.

Ellerman’s first job was as a pattern maker, and after three months she moved on to a job as a children’s-wear designer, which was something she had once sworn she’d never do. After nine months of that she was hired as a designer by Prophecy, at the time a $1-million-a-year concern with its headquarters in a part of downtown Dallas best described as located between the two bus stations.

Like all new fashion-house designers, Polly Ellerman did not come in and suddenly alter the look of Prophecy. But after a while she began to assert herself. She suggested that Prophecy pay attention to a new customer, one that she understood well, because she was that customer. Like Polly Ellerman, many of those baby-boomers were now skilled professionals committed to their work with the kind of determination that had once been considered the exclusive province of men.

Of course, clothes for working women were nothing new in the apparel industry, particularly in Dallas. But although the suits and dresses that had been designed in the fifties and sixties for the working woman were fine for Mom, they did not appeal to women who had grown up in the sixties. Around 1970 the New York firm Evan-Picone brought out a line of separates that translated the traditional suits and blazers into clean, natural silhouettes that were flattering and comfortable but all business. Evan-Picone was about three years ahead of its market, but after several years of losing money the line took off.

Polly Ellerman brought Prophecy in on the trail blazed by Evan-Picone, designing a career woman’s wardrobe that translated the versatility of Prophecy’s sportswear separates—which permitted women dressing on a budget to mix and match different pieces of a collection—into blazers, business suits, and dressy blouses and skirts that could be perfectly at home with all those three-piece suits in a corporate boardroom. “Man-tailored” and “dress-for-success” were becoming women’s-wear buzzwords, and the career woman became the industry’s most important customer. In 1978 Prophecy’s executives met with a group of management consultants and mapped out a five-year expansion program, and in the fall of 1980 they moved from their old downtown headquarters to the future-world vistas of far North Dallas.

Today Polly Ellerman, as vice president for design, heads up a staff of two associate designers, five pattern makers, six sample sewers, and two assistants. Prophecy’s future now depends on how well Ellerman, Abady, and the rest of the design team keep up with the career woman as her tastes mature and her image changes. Their job is complicated by the technical demands of an industry that recognizes five seasons of the fashion year—spring, summer, fall, winter, and what is variously known as holiday, cruise, or, at Prophecy, pre-spring—for each of which Prophecy cranks out about one hundred separate garments.

The design staff of Prophecy is situated on the ground floor right below the functional but plush executive offices on the second story. Ranked behind the design area is the industrial apparatus that makes the clothes: two-story shelves filled with fabric rolls, almost an acre of cutting tables where fabric is carved with jigsawlike, murderously sharp power tools, hundreds of seamstresses sitting in rows assembling garments from big stacks of cut cloth. Design, then, is the place where all of those grand marketing concepts generated upstairs come face to face with the problem of turning inarticulate fabric into a product that is expressive enough for its highly complex consumer.

A designer must make three basic decisions about every garment: what color to make it, what fabric to make it out of, and what shape—or, as they say in the trade, silhouette—to make it into. Ellerman and two associate designers work out those problems in offices with ground-floor views of the neighboring industrial monoliths. Their offices are strewn with the detritus of the first two decisions: piles of fabric swatches, color cards, paints, and spindles of thread and yarn. Silhouettes are worked out in small drawings, paired with fabric swatches, and assembled in a notebook that gives an overview of the entire line; those sketches are given to the pattern makers, who along with the sample sewers inhabit a mini-factory between the row of designers’ offices and the factory itself.

The pattern makers interpret the drawings into sections of heavy beige paper; from their prototype patterns they make a mock-up in muslin on the beige cotton torso of their dressmaker’s mannequin. If the pattern seems to fit properly it is given to a sample sewer, who makes the garment from the intended fabric. If it still looks good, a corrected master pattern is made and the factory seamstresses make thirty identical salesmen’s samples to be shown to retail buyers. When the orders come back from the sales force on the road and in the markets, Prophecy sets its production schedules, and its factories and contractors start producing the clothes that you see in the stores. Because design problems—the puckering of a sleeve, a print turned upside down—can materialize at any point, Ellerman has to keep up with every step of the process. She may end up spending a summer day thinking about colors and fabrics for spring, designing the pre-spring line, and worrying about snags in the production of the winter line.

The problems of imposing Prophecy’s design philosophy on this ceaseless cycle of production are complicated by the fact that the career woman is becoming harder and harder to figure out. She wants to wear clothing that is businesslike, but she is increasingly resentful of having to follow what amounts to a dress code because of the lack of variety on the racks. She doesn’t seem to want imitations of men’s styles anymore, either. “The personal, intuitive woman who has the confidence to do it her own way, who doesn’t want to be dictated to, is growing as a segment of the market,” says Abady. “She wants a collection that is a lot more avant, a lot more exciting. But I also have to figure out how to maintain that element that isn’t moving as fast. I don’t want to leave behind what I’ve got.”

Attacking that marketing conundrum is what design at Prophecy is all about these days. Abady shuns computer-printout-style marketing research. “The apparel trades are highly entrepreneurial and extremely intuitive,” he says. “You can’t do them like cornflakes.” He doesn’t solicit opinions from his retailers or their customers, but he does keep his ears tuned for information about his customers. A friend who worked for a chain of specialty stores told him of a problem that women were having with the full, ruffly “pretty blouse”: they liked the feminine touches, but they couldn’t put their old blazers and jackets on over it. Abady went to work streamlining the pretty blouse to make it more functional. Ellerman was active in a volunteer organization a year or so ago, and she had to attend a lot of black-tie affairs. She noticed that the elegant cocktail dress appropriate for such occasions was near extinction; her winter line will feature evening dresses to fill that gap.

Prophecy keeps an eye on color trends, relying on the multitude of fabric forecasts provided by the fiber industry, fabric manufacturers, and even a paid color consulting service. The trends serve only as a framework for making more subtle decisions. Last winter, for instance, was supposed to be big for gold and black—which it was—but Prophecy sensed an overkill coming and decided not to join the run. Sometimes, however, the design team will pick up on a certain-to-be-coming-out-your-ears color or fabric trend—like this winter’s silk taffetas—and do it anyway.

One thing Prophecy never does, though, is serve up clones of last year’s winners, a quality that many people feel is the principal distinction between a good fashion house and a schlock manufacturer. Abady also realizes that it doesn’t make economic sense to bury an old favorite just because everyone says it is gone. “The blazer is a big negative in the business today. But does the woman on the street know that blazers are dead? I always say that nothing ever goes from one hundred per cent to zero or from zero to one hundred per cent,” says Abady.

Ellerman goes to Europe once a year but avoids the couture shows. “There’s a big gap between those enormous Broadway productions and what people on the street are wearing,” she says. “The Europeans do lots of active wear and lots of dressy wear and not much sophisticated wear-to-the-office clothing.” It seems that Europe hasn’t progressed as far as the United States in its attitudes toward women, so European designers are missing out on the real women’s-wear action. Ellerman and Abady also go to New York periodically to look at fabrics, but they bring samples home before they buy, because the colors can look so different under the Sunbelt sun, where 60 per cent of Prophecy’s sales are made. And Abady takes the New York Times, but just to see who is the hero of the minute on Seventh Avenue. The Eastern Seaboard market accounts for 25 per cent of national retail apparel sales, versus 12 per cent for the Southwest, so New York designers simply have a bigger market to absorb their mistakes; Abady feels that he’s got to be more careful.

Fortunately, Ellerman is a designer with a measured feel for her craft. “Polly’s greatest strength is her sense of symmetry and proportion,” says Abady. “Nothing jumps out of her garments, like pockets too big or sleeves too full. She’s also very technically competent. She knows how to work out new constructions so that clothes look good on the body.”

As career women pull against the career woman stereotype, Abady sees more femininity in styling and Ellerman sees “more fun things,” like novelty pants. A few years ago Prophecy couldn’t give away wool clothes in the Southwest, but now its winter line is almost entirely wool. Prophecy maintains the flexibility to produce complex constructions in expensive fabrics by resisting “price points,” a theoretical ceiling beyond which a garment can’t go without losing the line’s usual customer. Prophecy’s avoidance of a convenient price slot can be confusing and frustrating to retailers, but Abady believes that customers, particularly during economic slumps, are looking for something special. “A woman buys with her heart rather than her head,” he says. “If you can put something out that she can’t live without, she’s going to buy it no matter what the price. In bad times, if she doesn’t see something better than what she’s got, she’ll stay with what she’s got.”

Abady isn’t kidding when he says he’d like to be as big as Levi Strauss, the nation’s largest clothing manufacturer. But he’s not going to do that by turning Prophecy into a monster. Instead, he’s buying up other labels—he recently acquired labels from Nardis, a respected Dallas firm founded in 1938, and he offered to acquire longtime Dallas fixture Victor Costa (Victor declined) with the apparent intention of becoming an apparel conglomerate. There are even rumors of a separate Polly Ellerman label. But when you ask Ellerman if she’d like to see her name on a label someday, she just blushes and says apologetically, “I can’t answer that.”

The fame of a fashion-house designer is fleeting, if it exists at all; who remembers Mary Greenburg, winner of the first Dallas Alice? The anonymous designer has always been the typical Dallas designer. These days she is most likely to be somewhere between twenty and forty, a college design-school graduate, and destined to spend her career working on clothes that will never reveal their creator. A restless fashion-house executive can always hope to see his name on a label—like Jim Heilman, the former Lorch executive who started his own company last year—but the typical designer goes on working for someone else.

The rule of thumb for avoiding that career trap has been to avoid working for a Dallas manufacturer. A better credential for an independent in Dallas is still a subordinate role in Paris, New York, or even L.A., anything but Dallas. That kind of thinking must change for Dallas to become more than a dumb design center, and that will take more than success stories like Polly Ellerman’s. Perhaps the person with the greatest potential to establish the Dallas fashion houses as a breeding ground for quality designers is Heather Morgan, who started the Heather Morgan Company late last year. She has drawn attention by bringing another dimension to dress-for-success (dress-after-success, really), and she is a 31-year-old design-school graduate with 7 years in the Dallas manufacturing industry behind her.

Heather Morgan was raised on a twenty-acre Mississippi cotton farm where food was abundant, transportation was limited to a tractor, and a new dress was the most exciting thing in her life. When she was eight her mother remarried, moved to Fort Worth, and started a boutique—a small sample shop in East Fort Worth that attracted the clients of the beauty shop directly behind it. At first Heather watched her mother go off to work and fantasized over the exotic evening clothes that Mom left behind in the closet, but she soon became involved in the business. She accompanied her mother to the markets at the old Dallas Merchandise Mart and grew up with the Apparel Mart. She started working in the boutique when she was eleven and was buying junior lines for her mother’s stores—there were eventually six of them—when she was in high school.

Morgan had always been a prolific sketcher, and she began to fill spiral notebooks with designs. Each notebook was dedicated to a different alter ego with a specific name and an extensive wardrobe; she called the sketchbooks names like her Betsy book or her Susie book. At first Betsy and Susie were into “real froufrou,” elaborate gowns fussed up with ruffles, feathers, and furs. The fanciful attire seemed like a gloss for Heather’s self-image: “I was fat and homely. When I looked in the mirror it seemed like I only had a torso.” In the ninth grade Heather lost weight, her natural beauty appeared, and boys began to notice her. For the first time Betsy and Susie acquired sportswear with flattering lines.

Heather had decided by the time she was in the sixth or seventh grade that she was going to study fashion design at Stephens College in Missouri, and when she got there she wasn’t disappointed. Entering freshmen were told exactly what their schedules would be for the next four years. The professors were all veterans of the business; theirs was a no-nonsense approach to concept and execution. Creativity was something that the students needed to restrain, not develop.

After graduation Heather taught college for two years (and learned even more from that experience than she had at Stephens), got married, went to Ohio and did freelance work for a manufacturer there, and finally decided that she really had to get into the business. What that meant to her was going to Dallas and designing for a big manufacturer.

Heather Morgan arrived in Dallas in 1975 and began making the rounds. She could only dream of working in the better houses, like Nardis, Applause, or Howard Wolf, whose designs were sold in leading department and specialty stores. She was thrilled to be hired by Royalty, a manufacturer of bottom-of-the-line synthetic garb for specialty shops and chain stores like Sears and J. C. Penney. Despite her extensive academic background, the business was something of a surprise. She had expected to come in and design wonderful clothes—and was quickly disabused of that notion.

But she learned. She saw that the real experts were the people who made the clothes, and while most of the other designers were disdainful of the “guys in back,” Morgan went to them with her questions. From the cutters, sewers, and pattern makers, she learned the secrets of making garments that need structural integrity as much as an airplane or a bridge does.

Morgan hammered sportswear, dresses, and missy and junior lines out of polyester. Sometimes when she was working late at night she would walk through the long racks of garments and say to herself, “God, I love this.” Today she is just as unequivocal in her enthusiasm: “I would recommend anyone’s starting in the chain business. You keep your humility, you’re more of a technician than an artist, and you learn how to design for the budget and moderate end of the market. And that’s where the money is.”

Royalty was troubled financially—hardly unusual in the revolving-door apparel business even in the best of times—and soon Morgan was bounced along to Stockton, a manufacturer for chain stores that had built its reputation on a pull-on denim pant. Stockton was a financially tight ship where each designer had to make her own patterns, which she turned over to her own sample maker, and to oversee her own cutting, an unusual procedure in a fashion house. When Morgan finally got to Applause, the job turned out to be an excruciating experience. Every afternoon the five designers, company president Richard Marcus, often his wife, and an occasional salesman or two would gather for creative meetings. Every garment was mercilessly assailed, and the atmosphere quickly grew paranoid and counterproductive.

At her next stop, Royal Park, she started out honing her design discipline under one of the most exacting masters in the business: sixteen-ounce polyester, known to those who are condemned to sculpt it as bulletproof. The principal virtues of bulletproof are its indestructibility and its ability to bind flesh as tightly as a girdle, producing a smooth contour in regions where madame’s physical fitness does not. The principal drawback of bulletproof is its resistance to all but the simplest forms of articulation.

Morgan gradually got more challenging assignments, like designing coordinated groups and separates, and finally she was appointed the designer for Royal Park’s brand-new Crystal Gayle line. For Morgan, it marked an opportunity to establish her own palette, to work with better fabrics, to enjoy the latitude offered by higher prices, and also to meet fashion writers and buyers in the better stores. Except that her name wouldn’t be on the label, here was a chance to have her own line. And when the clothing was first shown, amid extensive hoopla at the Apparel Mart, Morgan was shaking so violently that her fiancé had to put his arms around her to hold her in her chair.

The Crystal Gayle line had a two-year licensing agreement, but halfway through it Morgan realized that production and financial problems over which she had no control were terminal. It bothered her that executives who were disengaged from the making of clothes could doom a project, and it bothered her that they made lots of money while she got only a $2000-a-year raise for the responsibility of designing an entire line. By the time the Crystal Gayle line folded, Morgan had a 35-page prospectus for the Heather Morgan Company.

The first challenge for the new design entrepreneur was straightforward: find $300,000—the minimum needed to start a respectable line these days, given the expenses of fabric, labor, warehouse and office space, and promotion and given the fact that even under the best of circumstances revenues wouldn’t appear for nine months. So Morgan went to everyone she could think of who might be interested in such a speculative enterprise and encountered more crazies than she had ever thought existed.

In the midst of her nonstop supplicating, Morgan was persuaded to take a day off and join her mother and an old family friend for lunch. The friend was Marjorie Norman, who owned a property management company with her husband. While Heather waited for dessert, Marjorie turned to her and said blithely, “So when are we going into business together?” That’s when she found out that she finally had a backer.

By late 1981 Morgan knew that she needed to fine-tune her line for the career woman who was moving on. Like the planners at Prophecy, she figured that many women were in positions of authority and were no longer content to wear traditionally tailored suits and blazers. But unlike Prophecy, Morgan didn’t have a conservative constituency trailing her progressive customers.

To capture the attention of a buyer, Morgan starts with color. “A woman is going to go to color first when she walks into a store; she can’t even tell the style yet when clothes are hanging together on racks. I want her to think, ‘I haven’t seen that color before.’ ” She not only works from fabric samples but also tries to match colors she finds in photographs or paintings. Her fall line, for example, is based on what she calls Renaissance colors, with lots of rich, saturated purples and blue-greens played off against muted blues and grays.

Once she establishes the colors, Morgan sketches the entire line in one day to ensure that all of the designs relate to one another. Then she does finished sketches on graph paper; they are renditions in minute detail, down to the location of the stitching. She designs commodious but dramatic jackets with batwing sleeves, belted, tuniclike ponchos, and culottes and “banana” pants, all of imported wools, cottons, and silks, combining the insouciance of warm-up suits or active wear with the tailoring of a business suit. She’s directing most of her business toward specialty stores, which generally have less conservative customers than department stores.

The Heather Morgan Company went to its first market in January with its summer 1982 line. The market was abysmal—retailers are reluctant to take a chance on new labels or looks in times of distress—and her total sales volume for that first season was only $90,000, well under her conservative goal of $150,000. However, her fall line took off in last spring’s market (the plum mohair batwing sweater, plaid wool cape and scarf, and plum corduroy pants ensemble pictured on the cover of Women’s Wear Daily helped things along), where she did $250,000 in sales, and she expects a $1 million first year. But Morgan would like to keep her ultimate sales volume under $10 million a year, because she’s seen what undisciplined growth has done to some of Dallas’s largest manufacturers. “They didn’t put the money back into the business,” she says. “There were the planes, the boats, the boxes at Texas Stadium. The recession just culled out the ones who weren’t efficient, who couldn’t cut back.”

Personal control and the ability to target a market precisely are the advantages that a small manufacturer like the Heather Morgan Company can have over larger firms like Prophecy. Morgan does all the designing. She also meticulously reckons the cost of every button and seam on every garment and keeps a printing calculator on her desk, right between the phone and dozens of carefully ordered, perfectly sharpened colored pencils. Morgan brought her pattern maker, Betty White, with her from Royal Park because White had developed a feel for Heather Morgan’s fit and proportions; her only other employees are a sample sewer and a general helper. She’s represented in showrooms in Miami, Atlanta, Dallas, and Los Angeles, but New York is conspicuously missing.

Morgan may be onto something with her regional emphasis. Dallas designers were doing all right with the Southwestern stereotype during the fifties, but in the sixties and seventies the expansion-minded industry sacrificed its regional identity to gain a national market with all those utterly homogeneous dumb clothes. However, today’s Southwestern woman is less inclined to buy clothes dictated by New York or Paris. In fact, those sources are paradoxically encouraging her to ignore their trends. Unabashed regionalism may become the key to Dallas’s future as a design center.

Sandra Garratt works on a big white trestle table—around which her dog joyously roams and over which the white plaster ceiling gracefully peels—at her studio in a Maple Avenue apartment, an aging structure that is pleasantly out of keeping with Dallas’s rush into the 21st century. Like Polly Ellerman and Heather Morgan, Sandra Garratt is about thirty years old, a design-school graduate whose career has been profoundly affected by baby-boom demographics and the decline of European leadership. But Garratt never worked in the Dallas fashion houses, and her approach to designing for professional women is less conventional than Ellerman’s or Morgan’s. The scale of her business is measured at just over a hundred thousand dollars, but her operation seems to be on the verge of taking off. If that happens, Garratt will become the first member of Dallas’s avant-garde design community—a group of small manufacturers and one-of-a-kind designers who sell out of trendy boutiques and stage happening-type fashion shows—to have an impact on the streets.

As a teenager, Garratt split her time between England and California, and her first passion was ballet. While studying ballet in London in the early seventies, she got a job at Quarum, a trendy London design studio at a time when some of London’s designers were well in advance of Paris and Milan. Shortly thereafter she made three important decisions: to give up dancing because of chronic injuries, to study design, and to start thinking of herself as an American. She went back to California, enrolled in an accelerated program at the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising in Los Angeles, and earned her degree in two years. She got the same exhaustive technical training that is the staple of design schools everywhere, and while it didn’t exactly take with Garratt in the long run, she thinks that it was essential to her development.

Garratt’s first postgrad job was at Theodore, a Beverly Hills design shop. If London was, to Garratt’s sensibilities, ten years ahead of Europe, then California was a good five years behind. Theodore was the quintessence of Beverly Hills dressing, but Garratt’s next job was with Holly Harp, “the only California designer who had any respect on Seventh Avenue. She did really beautiful clothes, not play clothes.” Garratt then went on to Dinallo, a swank B-H design shop with workrooms above a boutique. Cost was no object for clients like Elizabeth Taylor, Raquel Welch, and Lily Tomlin. But Garratt soon decided that Los Angeles was insular in its tastes, so she left Lotusland and headed east.

New York in the mid-seventies was in the midst of history’s greatest fashion boom, thanks to Yves St. Laurent and his designer ready-to-wear. The abrupt ascendancy of the American designer had created a lot of confusion and frantic stylistic jockeying as American designers began to rival one another for fashion notoriety. The eye in the middle of this storm turned out to be Halston, and after a brief stint with Mary McFadden, Sandra Garratt went to work for him. From Garratt’s point of view, Halston was doing something quite different from everybody else. “It was a basic way of dressing that seemed to be suited to Americans. His clothes were realistic in the sense that they worked for you instead of your having to adopt the characteristics of the clothes.” Not only had Halston hit upon the revolutionary idea—revolutionary at least for a prestige designer—that the woman wears the clothes and not vice versa but he was also practical in other ways. Instead of wildly searching for a different look every year, he designed clothes that had a continuity of style, so that a woman could get years of service out of them and not feel that she had fallen behind. And Halston was audacious enough to use blended fabrics on couture designs, reasoning that “if you pay five thousand dollars for something, you don’t want to get off an airplane and have it wrinkled.” The only thing that kept Halston from being a thoroughly democratic designer was his formidable prices.

From Halston, Garratt went on to Zoran, a New York designer who also had some fresh ideas. He turned out a line based on one simple, square shape—a concept that Garratt herself had spent some time working with in school—but he used expensive, luxurious fabrics like crêpe de Chine and cashmere. Garratt couldn’t help but observe that Zoran had the same problem as Halston: the right idea at the wrong price.

By 1977 Garratt was married to designer Michael Garratt, pregnant, trying to get her own business going doing one-of-a-kind designs, and beginning to cast a jaundiced eye on the Big Apple. Michael Garratt’s brother was already living in Dallas and was one of the owners of the Gazebo, a fashionable boutique, and he could see the whole thing unfolding. “Come on down,” he told them, “it’s about to explode down here.” But after that buildup, Dallas seemed disappointingly nonvolatile. Garratt got a job doing display windows at the fashionable Marie Leavell dress shop but was fired for creating a provocative display based on the Seven Deadly Sins.

In desperation, she began to make the rounds of the fashion houses. The reaction to her portfolio was generally “I don’t think this is where you want to be working” or “You ought to go to New York.” On the way home from one of those unproductive interviews Garratt calmed herself with a therapeutic visit to a fabric store. She saw a lot of cheap cotton-polyester T-shirt knit on sale and decided to work on an idea she’d been carrying around for several years.

Sandra Garratt’s pet concept had started in design school with an independent study project. In what was at first no more than an intellectual exercise, she worked out a formula for designing clothes, breaking down the average-sized woman into body proportions and figuring out how her clothes needed to be proportioned for maximum aesthetic effect and comfort. She also speculated on the simplest, most economical way of constructing those clothes and came up with a set of patterns based on squares and rectangles, which were much easier to cut and sew and wasted a lot less fabric than designs with curved sections. But while the garments might look like minimal art off the body, they were extremely comfortable, their proportions had a surprising rapport with a woman’s body, and their modular forms were easy to combine and match with accessories. In keeping with their Erector Set functionalism, Garratt called them units.

Garratt loved fragile, romantic, almost ritualistic evening gowns, but her exposure to designers like Halston and Zoran had shown her the way things were going. “Those elaborate, formal clothes were dinosaurs,” she realized. “After all, couture itself had only been around for a hundred years. It was a wonderful experiment, but it was time for something else.”

Garratt left the fabric shop with enough T-shirting to turn out a line of units. She took them around to some of Dallas’s more avant-garde boutiques, and within six months the business was supporting itself. Expansion past that rudimentary point was troublesome for a while; she found a backer but that arrangement didn’t work out, and a partnership with some other designers broke up. Still, she built a small cult following by selling out of her studio and a few specialty stores, and her customers weren’t kids with purple hair. Among Dallas’s more progressively dressed working women, a Sandra Garratt became a symbol of high fashion consciousness.

The underground popularity of the units proved that Garratt’s seemingly esoteric theories were practical. Her line consisted of only four or five tops, a couple of cardiganlike, buttonless wraps to go over them, a jump suit, and shorts, skirts, and pants in a couple of styles each. All had the same boxy construction, were in cotton-polyester T-shirting or sweat-shirting, and came in black, white, red, and a few other colors that Garratt chose each season. The discount-house prices and the unwad-it-and-wear-it practicality of the line were bonuses.

This year Garratt has a new backer and, for the first time, is being represented in the Dallas, Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York markets. Whereas she once relied on a cottage industry of six seamstresses working in their homes, she now contracts with a factory to produce the units. And the slack economy merely increases her conviction that her approach is the way of the future. Garratt thinks the apparel business will polarize into a high end and a low end. “I think we’re going to see a sharper difference between everyday things and special clothes for very formal occasions,” she says. “With prices rising, who is going to pay a lot of money for something that’s just mediocre? The middle ground is going to drop out.” Garratt expects that the consumer who shops at the low end will look for the functional authenticity found in blue jeans or T-shirts rather than turning to cheap interpretations of expensive, traditional career-dressing styles; she hopes that the units will become a stylish, softer addition to those American vernacular classics. “I always thought that the best thing you could ever do,” she says, “would be to outdesign Levi’s and Fruit of the Loom.”

Todd Oldham is tousle-haired and boyish, wears baggy shorts and T-shirts to work, and doesn’t come close to being a typical Dallas designer. He is 23 years old, has no formal training, and bristles at the notion of being considered a Dallas designer: “I’m a designer who happens to live in Dallas.” Oldham has been manufacturing for a little more than a year and still needs financial backing to scale up his business so he can worry more about design than survival, but he is a scrappy, determined businessman and potentially an important element in Dallas’s design future. That’s because Oldham is one of the best representations anywhere of the next generation in design: a generation for whom the couture tradition, all-American kitsch, and dress-for-sex-appeal are no longer barriers to progress but nostalgic whispers from a vanished culture.

Oldham’s father was a computer specialist with Bell Helicopter, and his work took the family all over the world, including Iran, where they spent four years when Todd was a teenager. From that perspective, America always had a larger-than-life quality, and Oldham can remember the awesome, almost surrealistic impact of American culture every time the family came back from overseas. The experience gave Oldham a respect for some discredited elements of American suburban style and a yearning for its heyday in the fifties (for most of which, of course, he wasn’t around) and sixties: “I remember that my mother wore lots of patio shifts and capri pants, and I’ve always liked those K-Mart–Woolco sort of things. I’ve always liked the way Elizabeth Taylor looked in Butterfield 8 and Shelley Winters’s leopard-print cocktail dress in Lolita. And I remember women’s legs. I hate prairie skirts.”

Oldham had always planned to be a graphic artist, but his mother was an inveterate seamstress, and one day he decided to take a crack at her sewing machine. His first attempt to sew some pants was disastrous. He kept teaching himself, and by the time he was fifteen he had sewn the first dress that he really liked, a bright purple boat-neck shift with red piping and buttons down the back. It was cut free form, without the benefit of a pattern, and the sleeves ended up too long. Oldham decided to pull the excess up above each shoulder and simply sew it off, creating an unexpectedly stylish pleat. He had just learned that an untutored designer could turn his accidents into innovations.

Oldham was sixteen and living in Roanoke, north of Fort Worth, when he had his first professional success. He did an un-Oldhamesque gown for a voluptuous, blonde Fort Worth socialite to wear to the Thalians Ball in Los Angeles. The woman’s figure was highlighted by a black filigree that just barely crawled over her breasts (she added a black ostrich boa as an accessory), and her picture and Todd’s name made all the papers. From then on, Oldham had a business doing one-of-a-kind commissions, which is the professional entry level for most young designers who don’t want to go the fashion-house route. But after a bad experience with a customer who refused to pay, Oldham realized that one-of-a-kind production was neither aesthetically liberating nor economically efficient.

After a stab at selling a truncated, six-piece line of “diaper” pants and T-shirts in New Wave dress shops, Oldham got a job doing alterations for Ralph Lauren’s Polo line in Dallas. He worked with Bea Harper, one of Dallas’s most expert dressmakers, and received an education in what he calls the logistics of constructing clothes. But Oldham wanted to do things his way, and was soon out on his own again. This time he bought some white and cream T-shirt knit from a jobber house, a place that buys overstocked fabrics and sells them in smaller yardages than fabric manufacturers. Oldham and his mother—who is his business partner—hand-dyed the T-shirting in muted, off-color pastels, and Todd designed some loose-fitting separates that seemed to be influenced by the flowing, layered clothes worn by Middle Eastern peasants. He and his mother hand-sewed the entire ninety-piece production run and watched everything sell out at Neiman’s and at Cha-Cha’s, a prestigious local boutique.

With that success Oldham plunged into the big league routine of producing enough for five seasons a year and tried to hold together a shoestring operation in a no-frills co-op factory near the Apparel Mart; he paid a lot of his bills by doing knockoffs—adaptations or copies of hot designer items—and separates for department stores to sell under their own labels. For the fall 1982 season, Oldham got some backers and was able to put out a slick publicity brochure, design a hundred-piece line, and stage a sexy, well-produced showing in a downtown loft last spring. But by summer his backers had backed off, and he was scaling down his expectations and nursing his operation along again. However, he expects to get through this downturn with the equilibrium of a generation that has grown up in a jittery economy and with some old-fashioned family unity, with his mother working alongside him, his father helping to keep the finances straight, and his sister modeling in his shows.

Some of Oldham’s best touches come from looking at what the most ordinary people are wearing. One example is the genesis of the big, blocked, black-and-white patterns and stripes that key his fall line, which occurred when Oldham was driving on the tollway between Dallas and Fort Worth and noticed a group of men working at the side of the road in white overalls and black bomber jackets. On the other hand, Oldham isn’t reticent about looking toward Europe, where he admires Karl Lagerfeld, Claude Montana (who personally never wears anything except cowboy boots, jeans, and bomber jackets), and Thierry Mugler—considered to be three of Europe’s most advanced designers—and the master designer, Yves St. Laurent. What Oldham likes about those French designers is the spirit of their clothes—“a sense of fifties kitsch; fun, wearable, and always in style”—and the big runway blowouts with which they introduce their collections, a tradition that he reveres as an art form unto itself.

Oldham has the iconoclasm of a self-taught technician. A favorite motif is his circle-cut pattern that evolved when he wanted a pleated effect in a fabric that couldn’t be pleated; the result was a full, almost ruffly silhouette from a construction so simple that it would have been dismissed out of hand by a formally trained designer. Even Oldham’s more conventional patterns are unorthodox, with extra-big armholes and fullness in the body and sleeves, and he has had problems with pattern makers who try to correct his apparent mistakes. But Oldham feels that American clothes are sized too small—a legacy of another era—and women who have been turning toward voluminous silhouettes seem to agree.

Oldham also combines his unconventional shapes with unexpected accentuation and details. Sometimes the effects are deliberately humorous, like rust-and-black-striped pants with the fly lined in bright blue, a second collar on a blouse, or a long slit skirt with a miniskirt under it. Others add elegance to simple motifs; Oldham usually cuts stripes separately and stitches them together, giving an entirely different weight and texture to a basic striped skirt or shift. And other surprises are unabashedly sexy. Some are vampish, like the long slits in many of his dresses; some nostalgic, like tight miniskirts paired with those big tops; and others just titillating, like big-necked blouses that perch precariously on the shoulders. “I like the idea that a blouse could slip off the shoulder at any minute,” he says.

For all the stylistic flourishes, Oldham’s clothes also have the practicality that today’s market demands, to which Oldham adds a concept he picked up by watching the way people dress in the Middle East. “There is no such thing as summer or winter clothes there,” he says. “In the winter people just put more things on, and in the summer they just take more things off.” So Oldham bases his line on cotton pieces that can be worn alone in the summer or layered on top of one another in the winter; few things need to be put in storage bags with mothballs.

Oldham has a showroom only in New York, but he is comfortable with Dallas’s limitations. “Dallas isn’t New York,” he says, “and it doesn’t need to be.” He is also comfortable with his own limited reputation, hoping to pace his growth and avoid becoming an evanescent overnight sensation. “I want to grow gracefully,” he says. “I want to be around for a long time.”

The question of whether Dallas will become a major design center remains moot. If experience is any teacher, it will not, but experience is not always a good teacher, particularly in a field as unpredictable as fashion. What Dallas has going for it, it has had for years: good customers, good manufacturing and wholesaling facilities, and the simple fact that lots of clothes are made there. But that huge industry has often stifled local originality and indeed seems sometimes to exhibit a siege mentality, regarding any criticism of its lackluster design performance as an attack on the livelihood of Dallas’s tens of thousands of apparel workers. The reverse may well be true, as a recent spate of local industry bankruptcies indicates; many of the thriving companies seem to be the ones, like Prophecy, that are putting their money and creativity into the product, while the losers have been firms that have been unable to keep up with the consumer. Now even some boosters are unafraid to say that the industry needs more emphasis on quality design. And the Dallas Apparel Mart is starting to take an active interest in young, unproven Dallas designers, so that very visible arena is finally opening up to local innovation.

But perhaps Dallas designers are also fighting a general cultural malaise. The South’s most sophisticated city is a great consumer of culture, but it has never come close to being a great producer. In Dallas, culture is equated with the size and stature of institutions—with the kind of statistics that its mighty apparel industry so liberally provides—and little thought is given to individual creators. “Dallas is a city based on hope,” said one waggish observer of the cultural scene half a dozen years ago, and from the point of view of the designer, hope is still the local industry’s greatest commodity.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fashion

- Dallas