This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

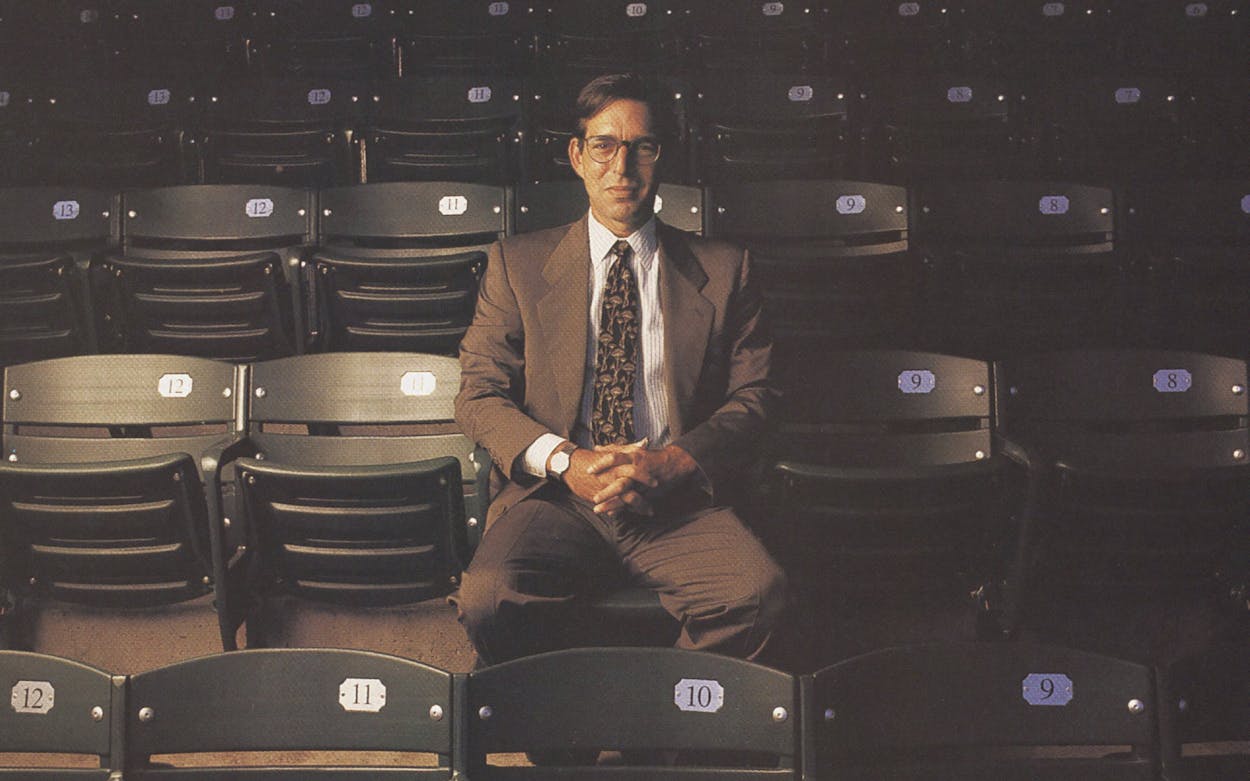

In the relatively brief span of eight years, architect David M. Schwarz has designed or renovated more than a dozen buildings—including a hospital, an eleven-screen movie theater complex, a $165 million major league baseball park, and a hotel—in and around Fort Worth. It has been an opportunity to shape and define an urban area that has been afforded no other architect in Texas or anywhere else in the United States in the last half of the twentieth century. The 43-year-old Schwarz has responded by giving his buildings a distinctive identity through ornamental devices—like Longhorns or Lone Stars carved into the facade—that announce that the structures could exist only in a city that prides itself as the place Where the West Begins.

Schwarz’s works are testament to his prodigious talent, but they also underscore the importance of the architectclient relationship—which in his case has made all the difference. Schwarz’s patrons are the wealthiest family in Texas, the billion-dollar Basses of Fort Worth.

Schwarz acknowledges their significance one summer morning when he emerges from a workroom in the bowels of the Worthington, Fort Worth’s premier hotel. “Sorry we’re running late,” he says, nodding toward the cause of his tardiness, Edward P. Bass—one of the Worthington’s principal owners and the one who hired Schwarz for a major overhaul of its interior. “No offense, but he’s more important.”

Half an hour has passed, and Schwarz is dashing across the lobby of City Center Tower I, Fort Worth’s tallest skyscraper and another Bass Brothers property, when he puffs breathlessly, “If Perry sees me, he’ll kill me.” Schwarz is hoping to avoid running into Perry Bass because the family patriarch is the one Bass who doesn’t much cotton to anyone’s wearing sandals, much less his architect.

The pair of Tevas he is wearing with his Armani suit complements the young face at the other end of his diminutive frame. The studiously offbeat effect makes it entirely plausible that the actual goal of Texas’ most prolific architect of the moment is not to build buildings but to engage in real-life child’s play.

To appreciate the considerable effect that Erector Sets, Tinker Toys, and Lincoln Logs have had on his design sensibilities, one need look no further than the atrium of the Cook-Fort Worth Children’s Medical Center, a mirrored illusion of fantasy castles and light, or its ironwork facade of tic-tac-toe grids; the art deco marquee and entrance of the Sundance 11 Cinema downtown; or the stucco facade he added to Fort Worth’s city library, which makes the building look three times its age. These places all suggest a Disney reality—simultaneously real and unreal, new and old—while also conveying a sense of history that distinguishes them from the Sunbelt-modern high rises that dominate downtowns and satellite cities elsewhere in Texas.

With the exception of just a few projects—including most notably the Ballpark in Arlington, which opened in April—most of the Texas projects designed by this aging wunderkind from Washington, D.C., have had some tie to the Basses, the Medicis around this part of the prairie. That has naturally inspired fits of jealousy and grumbling, mostly off-the-record and mostly from other architects, to the effect that Schwarz builds kitschy buildings that pander to the public’s infatuation with nostalgia, not to mention that he’s a carpetbagger, and worse.

He rode into Cowtown a dozen years ago at the behest of his D.C. lawyer friend David Bonderman, who had been hired by Robert M. Bass to fight an attempt to widen the Interstate 30 overpass on the southern edge of downtown Fort Worth. Bonderman had Schwarz testify as an expert witness and explain why several historically significant buildings would be better served by building a bypass farther south. Bob Bass, who would later be appointed board chairman of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, subsequently engaged Schwarz to redo his vacation cottage in Maine and restore the former Ulysses S. Grant residence that he had bought in Washington’s Georgetown neighborhood. Bass liked Schwarz’s work so much that he used his influence as chairman of the Cook-Fort Worth Children’s Medical Center board of directors to award Schwarz the commission to design a new hospital. In the meantime, Bonderman had moved to Fort Worth and hired Schwarz to remodel his new home. Schwarz began to get so much work that he decided to set up a branch office in the city.

In 1987 Bob’s brother Ed hired Schwarz to design and build Sundance West, a thirteen-story residential high rise with stores, restaurants, offices, and the Sundance 11 movie theater complex. It was the beginning of a long-term relationship that owes much to their both having gone to Yale Architecture School, although at different times. “Ed and I are a good marriage of architect and client because we agree,” says Schwarz. “Both of us are very concerned with building a rich urban environment. ”

The demise of Fort Worth’s city center, which began in the late sixties and extended into the late eighties, was “a piecemeal effort that sacrificed old buildings, some of the few remnants of history, for surface parking lots,” Schwarz says. “My goal was to give the city a good urban fabric again. ”

Schwarz attributes his understanding of Fort Worth’s particular urban dilemma to his having grown up in Southern California. “What happened was that the greatest period of growth on the West Coast and in Texas was after World War II, when cars came into prominence,” he says. “Cities were designed to facilitate cars at the expense of pedestrian areas. But the idea that Texans won’t walk is a myth. It’s hot here, but give the people shade and a reason to walk, as the River Walk in San Antonio has, instead of acres and acres of parking lots with no trees, and they will get out of their cars and come.”

Now people are returning to downtown Fort Worth after dark to fill the streets and sidewalks as well as the buildings. The apartments and condos of the neoclassic-style Sundance West were fully leased before opening day. The American Movie Corporation’s Sundance 11 Cinema is the chain’s highest-grossing location in North Texas and the perfect complement to Ed Bass’s Caravan of Dreams next door, one of the best music venues in the state. The hallways of the Worthington, once cold and impersonal, have been made warm and comfy. “Modern can be nice,” Schwarz says, pointing out a futuristic sink in the Van Cliburn Suite. “It’s not an issue of style. It’s an issue of details. Look at the Ballpark. People say it reminds them of Boston and Fenway Park. But look at the airplane tension wire on the handrails. Look at the glazing detail on the border of each tier. This is a combination of old and new. ”

On a grander scale, the Ballpark represents an attempt to give Arlington, a suburb without a center, its first pedestrian-friendly neighborhood in fifty years. When completed, the project, which was funded by a city sales tax, will include a concert amphitheater, two lakes, a park, a youth sports complex, restaurants, shops, hotels, and residences. “The Ballpark does not sit in the middle of a parking lot,” Schwarz explains. “It sits on the curb. What comes next is the streetscape between the Ballpark and the community.”

Schwarz’s latest assignment is a two-thousand-seat beaux arts performance hall in downtown Fort Worth, scheduled for completion in 1998. The $60 million facility, for which Ed Bass has spearheaded the fundraising, offers Schwarz perhaps his best shot at fame. Crammed onto a forty-thousand-square-foot city block, the world-class concert hall will have one of Schwarz’s “old” exteriors of granite and limestone and, flanking the entrance, two forty-foot angels with trumpets.

“I’m not particularly concerned how a building is received the day it’s done,” Schwarz says. “What matters is how people who use the building forty years from now are going to like it.” Only time will tell if the performance hall, the Ballpark, or Sundance West will prove to have the staying power of Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Museum, Philip Johnson’s Pennzoil Place, or, for that matter, the Alamo. Meanwhile, the imagination of David Schwarz has left its mark on Fort Worth and Tarrant County. You may call his style neoclassical Post-Modernism or some such. But whatever you call it, it is making Fort Worth look more like Texas than any other city in the state.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Architecture

- Fort Worth