This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

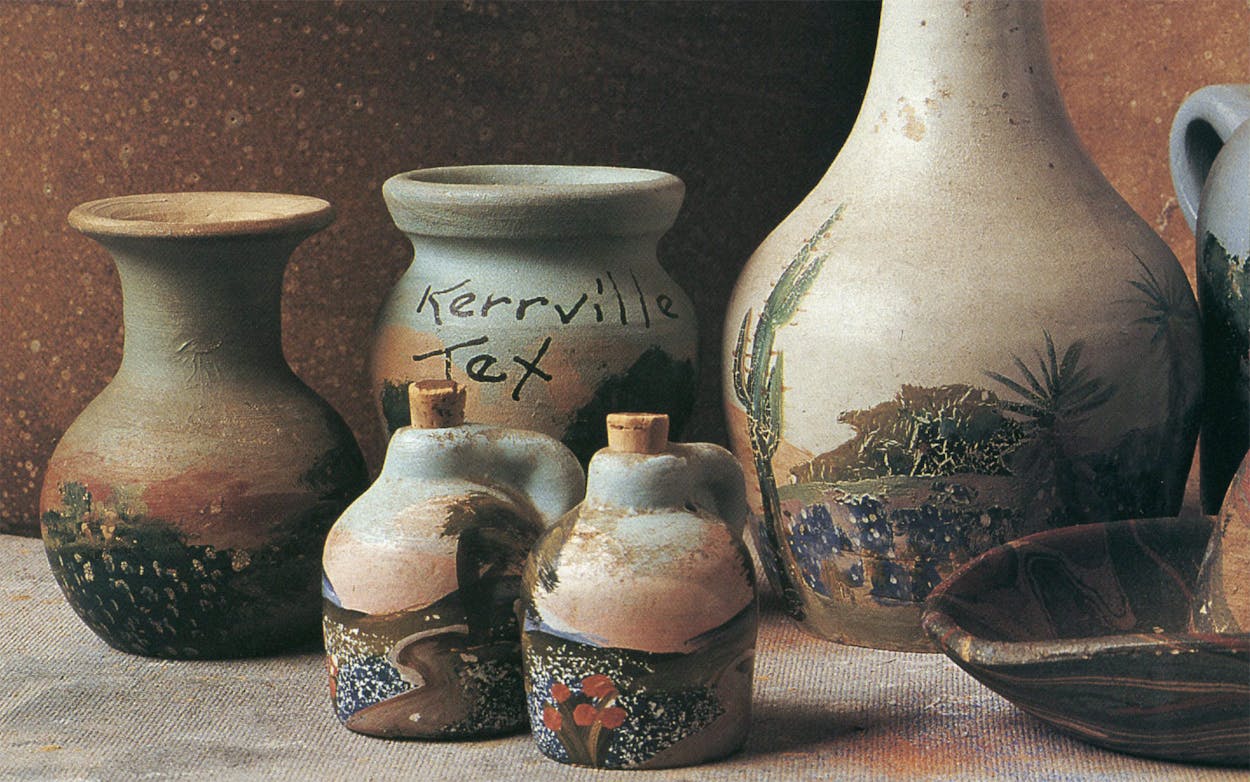

In the early seventies San Antonio pediatrician and American pottery expert Georgeanna Greer wrote a small tome on the sturdy, handsome stoneware made by the Meyer Pottery studio in Bexar County. Her work, coinciding with Texans’ desire to embrace their own folk art, helped catapult Meyer’s turn-of-the-century crocks, jugs, and pitchers into bona fide antiques. Today our postmodernist aesthetic, coinciding with an unseemly appreciation for kitsch, has stimulated interest in Meyer pottery once more. But this time collectors crave the cheap, raffishly decorated souvenir items that the company produced in a last-gasp attempt to stay solvent. They have become, in the current vernacular, collectible. Instead of the early work’s straightforward shapes and forthright colors so in tune with modernist dictates, these squatty pots and souvenir sombreros, introduced in the late twenties, are decorated with swirling colors and desert or bluebonnet scenes painted by anonymous Mexican women. Popularity has produced exuberant prices too, though not in the rarefied stratum of the early pieces ($700 for a five-gallon jug). Houston antique dealer Rick Jones just shipped his whole inventory of some 48 pieces to a collector out of state at figures as high as $95 each—a pretty hefty sum for objects that originally sold for a couple of dollars a dozen.

This newfound celebrity would surely have been unimaginable to German immigrants William Meyer and Franz Schultz, Meyer’s father-in-law, when they founded their pottery business in Atascosa in 1887. Their aim was simply to produce and sell functional household items slip-glazed with clay from nearby Leon Creek. The company’s economic hardships began after World War I, when metal, and then plastic, replaced clay as the stuff of domestic housewares. By the forties, the company was forced into producing ashtrays for the Buckhorn Saloon, bookends for the Alamo, mugs for visiting Shriners, tiny sombreros for tourists. The items sold for pennies, pennies that could not prevent the Meyer Pottery from closing its doors in 1964.

Greer’s book set off the first wave of Meyermania. Among those caught up in that whirlwind was William Meyer’s granddaughter, Helen Simons, whose husband, Tom, says he “went out in the yard and got the dog bowl and polished it up.” The value of the souvenir pieces can be partly determined by the dexterity of the painting. Tom Messer of San Antonio’s Horse of a Different Color claims a sign painter named Gonzales produced the most desirable work, while Simons believes a local artist she calls Mrs. Kolunko originated the themes that other artists subsequently imitated.

Not everyone shares this appreciation of Meyer’s gaudily painted pieces. Houstonian Robert Cochran, a major Meyer collector, assigns a tiny portion of display space to the stuff, saying, “You can only have so much of it.” Jeffrey Tucker—another Houston collector who so reveres Texas pottery that he suggests viewing times for his extensive collection according to the most becoming light—begrudgingly admits the later work is “interesting,” but only as “part of the larger story.” And as for the redoubtable Dr. Greer, the Meyer consecrator herself, she confesses to owning “a bunch, but it’s so ugly I keep it in the attic—it’s really pretty hideous.” Yes, and Cinderella was kept out of sight too.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- San Antonio