Annie O’Grady might be the quintessential Kendra Scott fan. The 27-year-old substitute teacher lives in Austin, where Scott’s jewelry brand is based, and owns at least fifty pieces by the designer. She began collecting Kendra Scott when she was a teenager. In high school, she noticed that many of the women she admired, including Taylor Swift, were wearing the line’s dangly statement earrings, and she wanted in as soon as she could afford them.

O’Grady’s first acquisition was a pair of Scott’s signature, oval Danielle earrings in tomato red, purchased on sale. She wore a pair of the line’s iridescent lavender earrings to her first college formal. For her wedding day, she selected feather-shaped crystal ear climbers.

But earlier this month, O’Grady came across a TikTok video that caught her by surprise. It was posted by Roberta Blevins, a leader of the movement against multilevel marketing (MLM), in which independently contracted salespeople hawk a retailer’s wares and recruit others to do the same. Blevins, who has more than a quarter million followers, explains in the video why she believes Scott’s move to beta test a direct-sales platform resembles an MLM scheme. “My heart just dropped,” O’Grady says.

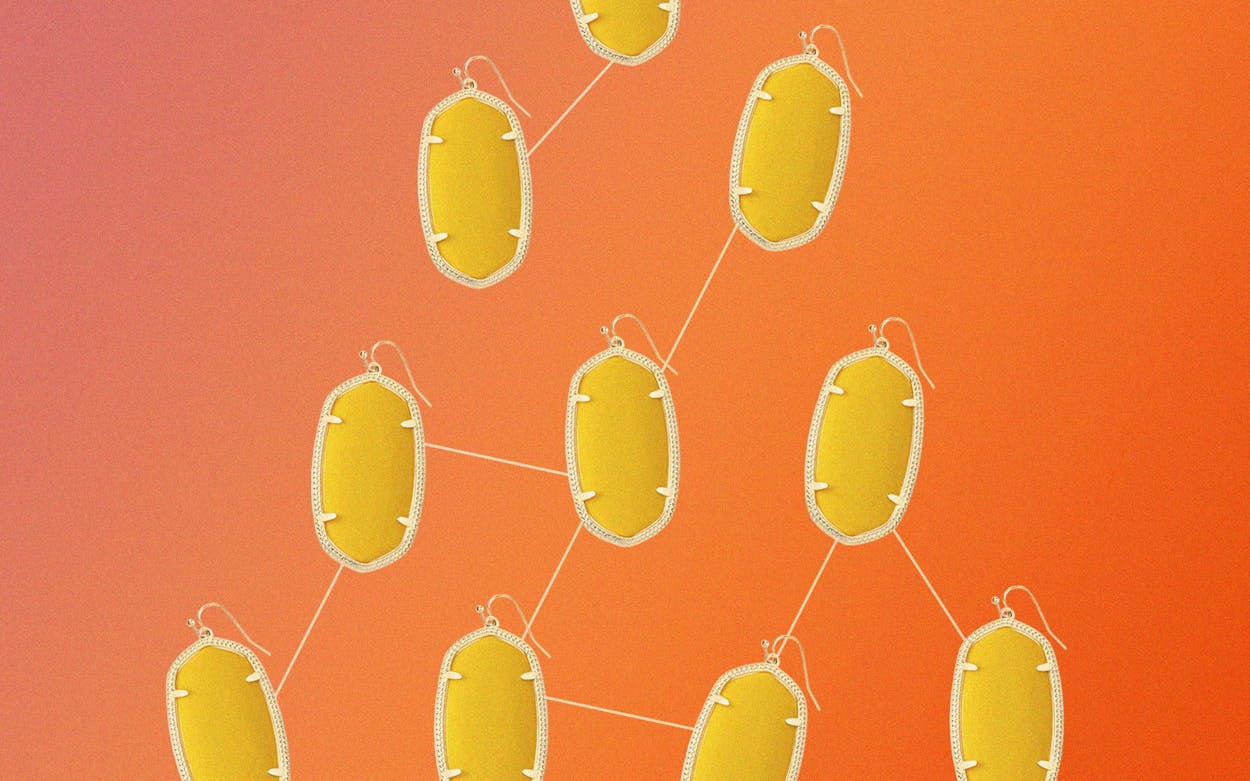

It’s easy to lump direct-sales brands such as Addison-based Mary Kay, Amway, and the controversial LuLaRoe into one bucket of neighbors and Facebook friends imploring you to buy their products. But there are two main types of direct sales: single-level marketing, in which individuals are compensated for the sales they make, and the more pyramid-shaped multilevel marketing, in which each salesperson earns mainly by recruiting other salespeople. Direct Retail by Kendra Scott is currently set up as the former; its marketing materials label it “a program developed to fill the gap for women who expect more for their life and from their job.”

“Community stylists,” the materials explain, will purchase kits of Kendra Scott jewelry priced from $199 to $1,499, designed to serve as showpieces for their customers, who then order the products online from the stylist’s dedicated link. For the service of gathering jewelry orders from family, friends, and other shoppers whom the company “does not reach through wholesale or retail,” the salesperson will earn commission ranging from 20 percent to 35 percent, depending on their monthly sales volume.

Within those marketing materials are assurances such as “No building teams or recruitment,” “Zero inventory in hand,” and “No sales goals, selling requirements, or personal volume requirements”—all terms suggesting Kendra Scott is trying to prevent this program from being mistaken for an MLM. On Facebook, the announcement was met with enough angry comments that the brand stepped in multiple times to make it clear: “We are not launching this program as an MLM. Our Direct Retail platform is built as a direct selling model with no emphasis on recruitment or building teams.” (Eagle-eyed fans may note the word “launching” leaves the brand with wiggle room, should it later decide to expand the program to a multilevel operation, as Avon did.)

Where O’Grady sees “a hot-button topic,” Stanton-based gun-shop owner Shelly Cook, who is 42, finds only financial opportunity and community connection. She plans to submit an application, hoping to be one of the few independent stylists from her town of fewer than three thousand people to get in. Her friends and neighbors around Midland may be the exact demographic the company is hoping to reach—potential shoppers in places where retail stores aren’t easily accessible.

Cook has participated in direct sales before through Scentsy, an MLM centered on sweet-smelling home goods such as diffusers and room sprays, and says the experience was a positive one, in that she could set her own work hours, throw product parties with friends, and earn extra income. While Cook hopes she can earn some money from the Kendra Scott program, she mainly sees it as a social opportunity. “For me, the plus side would be sharing it with friends and the fellowship that comes with that, and if I’ve made some money with it, that’s great,” she says. “This is a way for me to get out of the house, to break up the mundanity of everyday life.”

Raji Srinivasan, professor of marketing at the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin, speculates that Kendra Scott may be trying to capitalize on the “Great Resignation” that is happening across the nation, with workers leaving their jobs in search of better pay, benefits, working conditions, and control over their schedules.

At stake for Kendra Scott here is more than just a brand reputation. It’s also the reputation of its founder and namesake, whom most of our sources spoke about interchangeably with her company, even though Scott stepped down as CEO last year (she remains executive chairwoman). Scott’s influence, especially among upper-middle-income women, is still profound. She’s a recurring investor on Shark Tank, the reality TV show for entrepreneurs, and is the founder of the Kendra Scott Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership Institute at UT Austin. (Officials of the institute did not respond to Texas Monthly’s request for an interview about the Direct Retail program.) Just last week—only a few days after the direct-sales announcement—Kendra Scott (the company) previewed an upcoming bridal collection with popular Texas influencer Emily Travis, and Kendra Scott (the person) announced a forthcoming memoir called Born to Shine.

In response to an interview request from Texas Monthly, a company representative shared the following statement: “At Direct Retail by Kendra Scott, we are not an MLM. Family, Fashion, and Philanthropy are at the heart of what we do and the reason why we created this program: to empower female entrepreneurs. We will have a small number of stylists working in various communities where we do not have a strong presence. Building teams, recruiting others, and holding inventory is not a component of our program.”

As Srinivasan points out, the Kendra Scott brand has thus far been synonymous with a luxurious retail experience—think champagne tastings and petit fours. The brand’s more than one hundred stores across the country, which are elegantly designed with jewelry-customizing stations known as “Color Bars,” tend to be located in high-end shopping areas. A direct-sales program means “giving up control of their brand,” Srinivasan says, and relying on independent contractors to set the tone for the business. That tone will vary as much as its salespeople will. The new tone could be set by a cozy gathering in a friend’s basement—or by a Facebook message from a former roommate you haven’t spoken with in a decade.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Business

- Austin