This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Ponytails have held a certain allure for me ever since I had my first encounter with one on B Street at Scott Air Force Base, Illinois, in 1964. I was seven years old, and the girl whose lustrous brown locks were gathered into a ponytail was Janice Orrell, my next-door neighbor. Janice had a carriage and sophistication beyond her eight years, since she took ballet in nearby Belleville. She seemed to me something ethereal and otherworldly—for the first time in my life, I was realizing that there was something different about girls.

The afternoon that began my love affair with ponytails was one of those muggy, oppressive summer days that turned the wavering cornfields beyond the base’s chainlink fence into an Illinois Sahara, but it was cool at the Orrells’. Why I was there I couldn’t tell you. I should have been out with the guys playing kick the can or running around in the smoke of the DDT truck, but instead I was sitting on a couch with Janice, talking. Her mother had gone to the commissary, her dad was at work, and her little sister, Jeepie, was asleep upstairs. I remember that the Orrells’ house smelled funny, not like our house. From the kitchen came the aromas of herring and smoked sausage. Cartoons were playing on a black and white TV. A window fan blew loud streams of air over the couch.

Janice, still wearing her black leotard and white tights from ballet practice, gave me a long look, her deep brown eyes burning with the knowledge born of experience, and said, “Do you want to see something?”

She got on her knees on the couch, put her face right up to the plastic grille of the fan, and said in a growling, monsterlike voice, “I am the Shadow, and the Shadow knows. Bwah, ha, ha, ha, ha!” But I wasn’t paying attention. My brother had been doing the same trick for years. I was watching Janice’s ponytail. It was dancing behind her in the wind of the fan, weaving and flying and zipping around, hypnotizing me. It was tied with a red silk ribbon, and wisps of gold-flecked hairs were caressing the nape of her neck. Then I saw the tiny beads of perspiration on her naked shoulder blades, and the smooth line of her back. Seized by something I didn’t quite understand, I grabbed Janice and said, “Kiss me,” and brought her face to mine, just like in the movies. She ran to the bathroom to wash her face, ruining the moment, but I knew I had glimpsed something wondrous that day.

Ponytails continued to haunt me through the years. When I was sixteen and working at the photo counter of a Skillern’s drugstore in North Dallas, the world stopped revolving whenever Donica Folse walked in. A doe-eyed Hockaday School sophomore, Donica, whose name I learned after she got a prescription filled one day, came in a few times a week to buy makeup and Seventeen magazines. She was tall, maybe five eight, and she had the thickest, longest brown hair I’d ever seen. Her long, tanned legs, her sweet blue eyes—you nearly missed them because of that hair. Sometimes in the summer she’d stroll in wearing sandals, a bikini, and a stretched-out white T-shirt, and her glorious hair would be pulled back into an amazing ponytail, a ponytail that created its own mythology. Even the pharmacist would say something like “Golly” whenever Donica Folse walked in with that dizzying mane bobbing in the refrigerated drugstore air behind her.

Maybe it’s a twist of fate, but the girls I’ve dated have always had short hair. They were cute, they were funny, they were great at parties, but they were physically incapable of wearing ponytails. Not that I minded too much. I guess I thought ponytails only belonged to goddesses who are always just out of reach—like Donica, over there spraying Chantilly on her wrist at the cosmetics counter, and Janice, whose “Yuk!” could be heard over the sound of the tap water. In real life, the girls I took to proms and wrestled with in the back seat of my dad’s ambassador never had to brush their hair on dates and wore earrings you could always see.

At least that’s how it was until last winter, when I met a blue-eyed, blond elementary school teacher named Sandy Olson. She was hip, smart, hilariously funny, responsible, a great dancer, and given to making inappropriate phone calls late at night—everything I love in a woman. When I told Sandy I was writing a story about ponytails, she seemed amused. I went by her house that night (we were going to a movie) and was stunned when she came to the door. There, cascading down from the back of her head, was an angelic burst of golden hair, gathered in by a little maze of barrettes. She was 21 years older than Janice Orrell had been on that couch back in Illinois, but the same feeling overcame me. After all those years, paradise was within my grasp. I envisioned a future for Sandy and me. At our wedding I’d wear gray, she’d wear a ponytail. We’d move into our first house, and Sandy would unpack books, the sleeves of her sweat shirt rolled up, beads of perspiration forming on the back of her neck, just past that shimmering, perky bundle of yellow. Soon there would be a couple of little girls wreaking havoc in the kitchen, helping Mommy bake cupcakes, their tiny ponytails spotted with chocolate and powdered sugar.

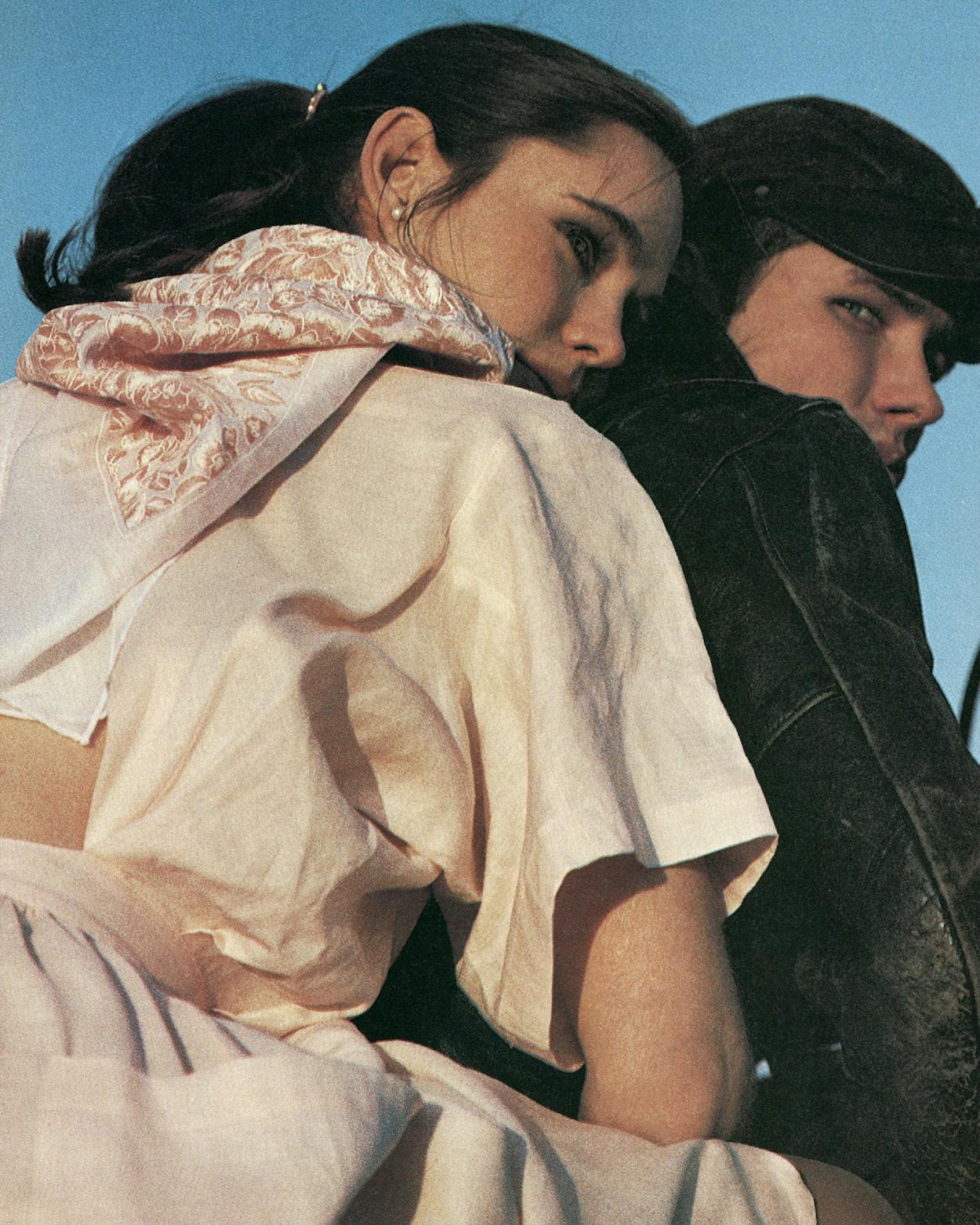

But things seldom work out the way you want them to. Three weeks later Sandy threw me over for a doctor from Galveston. The woman I’m seeing now is a punk rocker–cocktail waitress whose hair is shorter than mine. She’s physically incapable of looking anything like the woman on these pages. Sometimes at night, when I’m lying on my futon, awake and alone, I try to remember that she’s a great dancer, and sometimes I can even convince myself that that’s enough.

David Seeley is a freelance writer who lives in Dallas.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- Fashion