On the day Michael Uspenski and I met, we slapped each other with brooms of oak branches. The practice, called platza, is a therapeutic treatment traditionally performed in a Russian sauna known as a banya. The treatment is usually performed while the client is nude, lying on a wooden bench in a crowded and oppressively hot room. A steam master, or banschik, slaps their back with stinging oak and birch branches, or venik. Moving with the swagger of a coyote, Uspenski showed me how to swing the venik high in the air—to catch as much hot steam as possible—and bring it down onto the person’s body, sinking the heat through the skin and into the muscles and joints, relieving stress and pain while the leaves exfoliate. This treatment at the crossroads of pain and pleasure, which will run a customer $35, is meted out at Uspenski’s Russian Banya of Dallas, in Carrollton, the only Russian health club of its kind in Texas.

Uspenski was an activist back in Russia, operating during contentious times in local elections. In 2017, on vacation with his family in the U.S., he said he “received several uncomfortable messages—really threats—and we decided not to come back to Moscow.” He applied for political asylum to stay in the country and got an entry-level job as a claims analyst for a medical insurance company in the Bay Area—despite the PhD/MD in virology and microbiology he earned in Russia, where he spent decades developing hepatitis vaccines. Like many banya lovers far from home, Uspenski made a ritualistic, ninety-mile excursion from his house in Sacramento to San Francisco every week to use the legendary Russian-owned Archimedes Banya. “Banya is my love,” Uspenski said. He told me about sitting on a bench in a banya in Russia during his activist days, sharing a conversation with a KGB officer. “We’re friends in banya. Outside, I could have been arrested by them or tortured,” he said.

At Archimedes in 2021, Uspenski learned that a banya in Carrollton was for sale. The establishment had gone through several owners, and Uspenski decided to buy it and move to Texas to run it, sight unseen. “We sold everything. I sold my car, packed up, and moved here to Dallas,” he said. He’s been renovating, rebranding, and growing the business since.

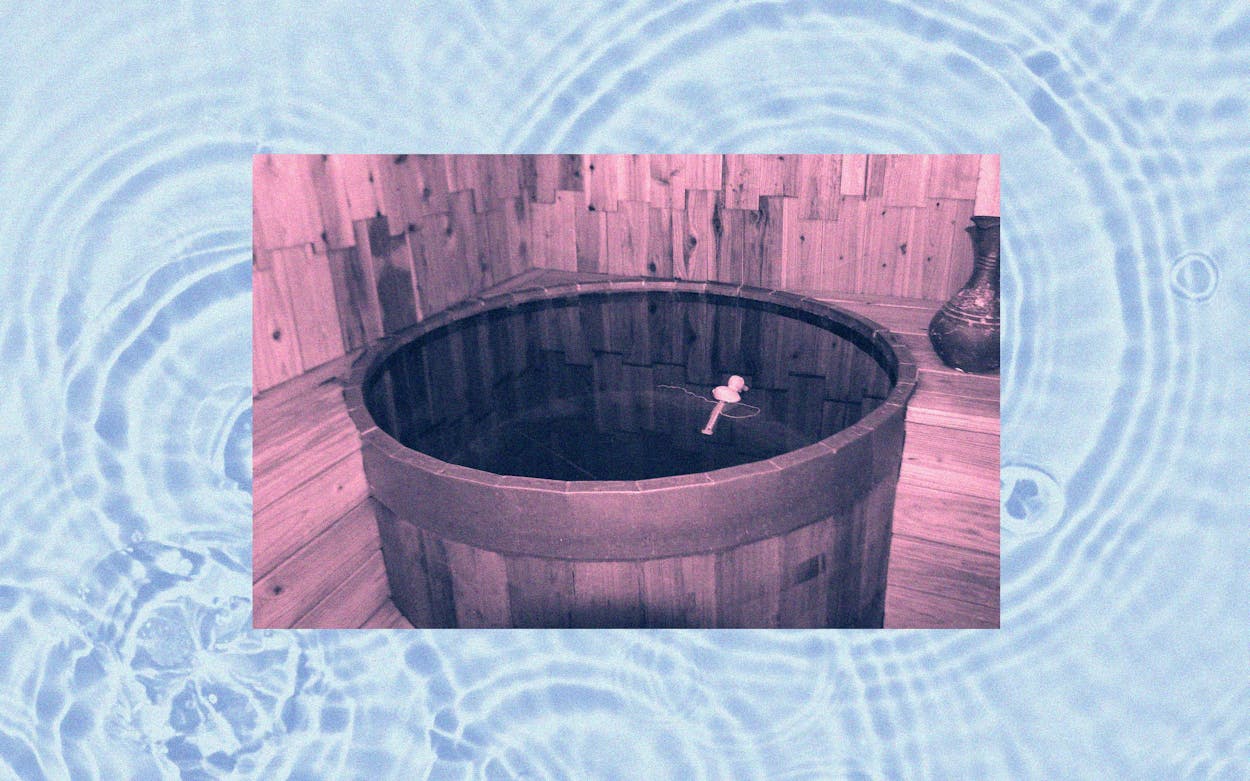

True to tradition, the establishment offers a humid, 180-degree Russian banya, as well as a dry Finnish sauna, a steamy Turkish hammam, and a cold-plunge pool. When guests sweat up an appetite, there’s the excellent and ludicrously well-priced Restaurant Volga, which serves traditional Russian and Ukrainian food. (The shuba, or herring dressed with beets, runs at $10 and an order of the vareniki, potato- or cottage cheese–stuffed dumplings, costs $8.)

The goal of the banya is to turn heat into a therapeutic treatment. Platza elevates the experience, though regular banyagoers do not always purchase a formal platza treatment from the steam master. You may see paired-up friends performing platza on each other with branches they either bring themselves or buy from the establishment. Most banyagoers, though, enjoy the heat of the sauna on its own. According to Uspenski, the spa attracts a mix of native Texans and Eastern European expats. Much like with his treks to Archimedes, people drive from San Antonio, Austin, Houston, Lubbock, and even out of state to experience the banya. On an evening I went, a player for the Dallas Stars—famous among the Russians—stopped in for a platza.

“Basically, I’m here five days out of seven days,” banya regular Jimmy Machock told me. A native Texan, Machock works in finance and finds the stress relief of Uspenski’s banya integral to his routine. “The therapeutic effects on the cardiovascular system are very well-documented for the banya, in terms of the dilatory effects on your arteries, your capillaries, all things that help with blood flow,” he said.

Others say regular treatment eases anxiety and platza helps keep skin youthful. For those who get hooked, the heat reigns supreme. “I was surprised I would actually like the heat again,” Machock said. “That aspect of my life was over thirty-five years ago from playing football, and I was really surprised that the heat is something I actually look forward to every day.”

On a recent Wednesday, Uspenski darted between banya tasks: heating the wood-burning stove, greeting people in the lobby, and leading patrons through a group aromatherapy treatment. Clad in a towel, Uspenski poured a mix of solutions—including vanilla, lavender, and, surprisingly, garlic—onto a bed of hot rocks, erupting a cloud of steam he fanned onto everyone with a sheet of fabric stretched between two wooden rods. All through the night, he made time to chat with each customer. “He kind of deals easily with all walks of life,” Machock said.

Uspenski’s nonchalance speaks to the ethos of his business. He hasn’t fully left politics behind—on Cinco de Mayo, he held an event to raise money for his employees who are Ukrainian refugees. Machock’s dad played original tunes for the party’s collection of regular spagoers, who all clapped and hollered along in Texas beer-joint fashion while shooting vodka and drinking margaritas on the rocks in towels and robes.

The sense of connection in the banya space is integral. The collective challenge of enduring the heat reminds everyone of the shared restrictions on our bodies. It’s an existential truth: we all will bail out of the banya at some point. “It makes you feel a part of human society, of the biological human society,” Uspenski said, echoing the language of his research field. “You feel the same; you feel equal to the others.”

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Dallas