This past fall, an iconic artist-built house just east of Lubbock was quietly sold by the daughter of its creator, who died in 2008. She says the selling price was $250,000, though the local realtor behind the company that bought it disputes that figure. About a month later, the agent listed the property for $1.75 million. The price dropped to $1.5 million in December, and the house was taken off the market soon afterward. The plan is to turn it into a vacation rental.

The structure in question is as much a sculpture as a home, an unfinished monument to what one individual can achieve through decades of effort on a single, quixotic project. The new owners have ambitions to finish the interior—though perhaps not in any way the creator would recognize. Architecture enthusiasts who love the building are distraught.

Welcome to the latest twist in the strange saga of the Robert Bruno house.

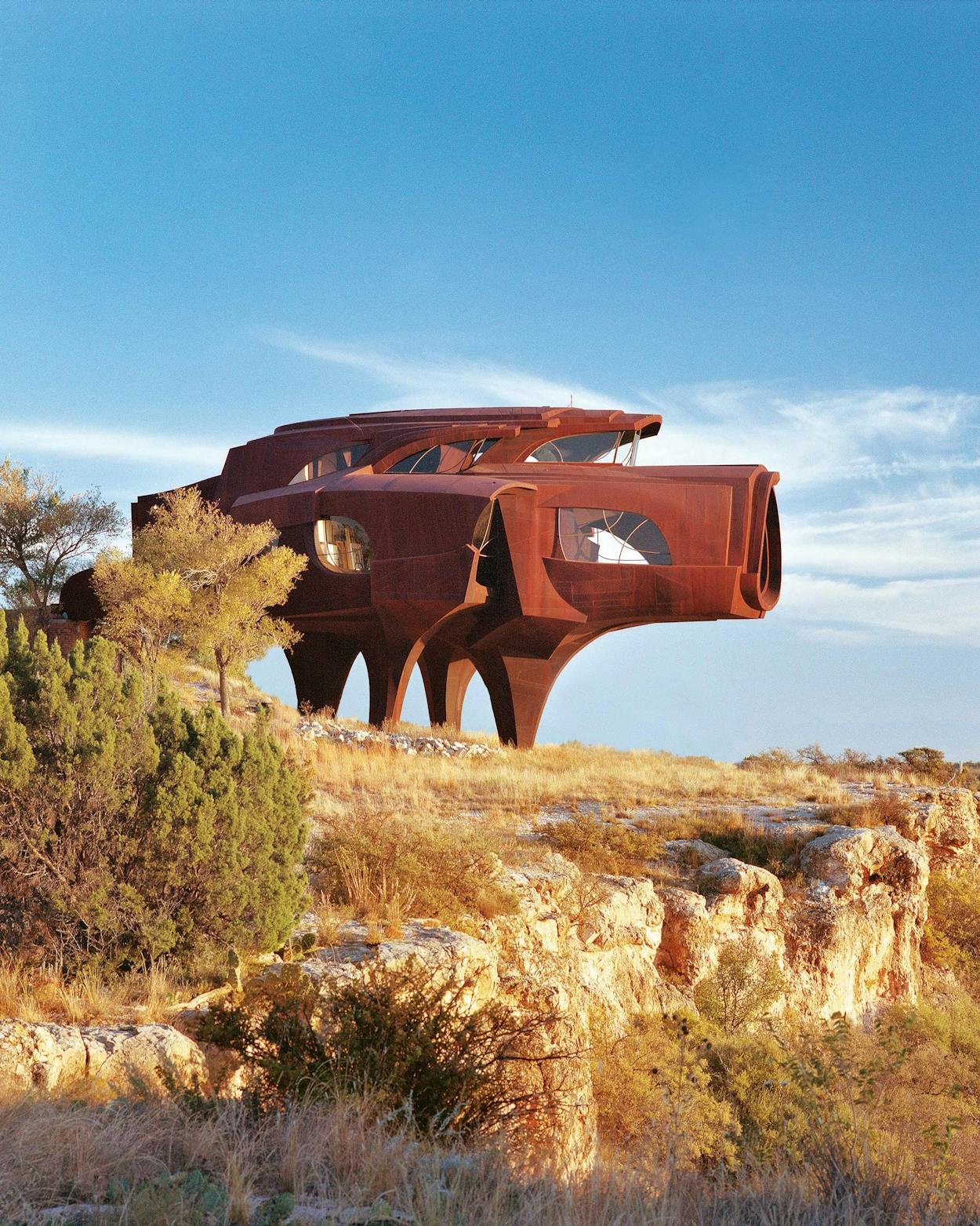

For decades, the edifice, also known as the Steel House, has been a part of Lubbock folklore, a local curiosity that students at Texas Tech University learn about through word of mouth and make short pilgrimages to see. (It’s located about fifteen miles east of campus, beside Lake Ransom Canyon.) It’s instantly recognizable: a gravity-defying, rusted, bulbous steel pod on four legs that’s served as the backdrop for a Vogue fashion shoot as well as a music video by Solange. Perched on a hillside, the structure has been compared to a pachyderm, the hull of a spaceship, and, in the words of Dallas Morning News architecture critic Mark Lamster, “the kind of house a James Bond villain might occupy.” One recent TikTok micro-review asked, “Is it a pig? Is it a gun? Can it move? Does it oink? We’ve got questions.”

This building was almost entirely the work of one man, Robert Bruno, who moved into the barely habitable house in the final months of his life, more than thirty years into its construction, so that he could finally experience it. It is no “machine for living in,” as the architect Le Corbusier once said about the function of houses, but a giant set piece for a sculptor’s unfettered imagination and a remarkable piece of architecture in a town with few examples of remarkable architecture.

Lubbock is an extremely conservative place, but it’s also home to a pretty good visual arts scene and is famously the birthplace of several outlaw country musicians. The area claims Buddy Holly, Waylon Jennings, Terry Allen, Natalie Maines, and a bunch of other hell-raisers, freethinkers, and eccentrics. Most of them get out of town as quickly as they can. But some do stay. For a certain type of individual—a figure who prizes the luxury of time; who views one’s work as a spiritual practice; who, say, wants to be left alone to spend decades building an astonishing house—Lubbock is an ideal location.

A California native, Bruno came to Texas in 1971 with his wife, Patricia, to teach architecture at Texas Tech. Lacking any formal education in the subject but trained in sculpture, the 26-year-old Bruno would be an unlikely pick for academia today. But at the time, the architecture program at Tech was just a department within the School of Engineering, and it needed someone to teach art. Bruno had taught sculpture at Brescia University, in Kentucky, and was willing to move to Lubbock and reenter higher education after stints as a jewelry designer and as a salesman at a department store. But he was dreamy and unorthodox, and he ruffled feathers at Tech, where the emphasis at the time was on the nuts and bolts of assembling a building—architecture as a vocation, not an artistic pursuit.

Bruno became part of a group of teachers and students who formed a strong bond, in the way that sometimes happens at universities, according to his former student W. Mark Gunderson, now an architect in Fort Worth. In the seventies, an architectural counter-wave swelled against the stripped-down, boxy modernism that prevailed at the time, and Bruno and his cohort were part of it. They discussed the inherent soulfulness of materials and deeply admired the utopian, organic designs of Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí. His unfinished, 139-year-old Sagrada Família church, in Barcelona, is often cited as an inspiration for Bruno’s own unfinished magnum opus, though they look nothing alike. (The only other building Bruno designed, the Stone House, down the road from the Steel House, appears more directly influenced by Gaudí, full of decorative tiles and curves.)

Bruno had been making sculptures out of steel since the sixties, when he was an art student at the Dominican College of Racine, a now-defunct Catholic school in Wisconsin. Over time his works grew larger and larger, eventually resulting in a massive, angular, four-legged sculpture he made after moving to Lubbock. The huge piece, with its thrusting, cyborglike snout, is beautifully pieced together from a patchwork of small pieces of steel. It sat alongside a friend’s cotton field outside Lubbock until 2015, when Tech acquired it from Bruno’s family for $35,000 and placed it in front of the architecture school.

That sculpture was the inspiration for the Steel House, in Ransom Canyon. Bruno’s only child, Christina Bruno, an art teacher in Jacksonville, Florida, recounts how her father would sit in the shade beneath it to eat his lunch: “He wanted to live in a space that felt like that, and that was the beginning of him building that house,” she says. He created his first drawings of the home in 1973 and received a permit to build on a 9,281-square-foot lot. (In those days, Lubbock permits had no expiration date, a practice the city has since changed.) He broke ground in 1974 and began working on the house in his spare time.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Bruno never became a tenured professor at Tech, but as it turned out, he didn’t need to become one. He was a talented engineer, and in 1982 he designed an innovative water valve for irrigation systems as a gift for Patricia, who worked for the local water district. The couple built a successful business around the valve and named it P&R Surge Systems, after their first initials. They got the company up and running and hired Henry Martinez, a Lubbock native, to help with manufacturing and assembly. That left Bruno more or less free to do what he wanted. And what he wanted was to weld steel into a huge, fanciful house.

The Steel House is made of quarter-inch Corten steel, a material commonly used in modernist sculpture but uncommon in architecture. Corten is a good conductor of heat, which means that it must be heavily insulated against Lubbock’s hot summers and cold winters. It’s also heavy. The house weighs 110 tons—about 10 tons more than a Boeing 757—which Bruno was able to calculate easily because he purchased the scrap metal he used by the pound. Martinez recalls that when he was a teenager, years before he went to work for Bruno, he would drive through Ransom Canyon with his father and see sparks flying through the air. “I asked my dad what they were, and he said, ‘Mijo, that’s a man building a house made out of steel.’ ”

For all its drawbacks, Corten steel also has advantages. It’s strong and can be torn down and rebuilt without any signs of damage. It was the perfect material for Bruno, who, over the course of the nearly 35 years he worked on the house, would frequently change his mind, cut out sections, and start over.

Bruno preferred to work alone, which would have been impossible without his engineering skills. He devised a homemade hydraulic crane that lifted him twenty feet off the ground in a makeshift chair. He would drive out to the site in his pickup truck, hoist himself up in the crane, and sit suspended inches from the surface of the house, studying every weld and every seam, tearing apart and rebuilding whole sections as he saw fit. His hands touched every inch of the thing. He worked surrounded by nature, and it’s easy to imagine him looking out at the lake and the canyon, contemplating the view as a type of meditation.

In a Texas Country Reporter interview recorded near the end of his life, Bruno said, “It would have been a lot easier to have a master plan from the beginning, but it wouldn’t have been better, just different, okay? Easy isn’t the only thing that matters, and if easy really mattered very much to me, I sure as heck wouldn’t be doing this. This is about spiritual values. The objective was not to move in and have a place to live; I can do that anywhere. The objective was to do something.”

related video: Texas Country Reporter

Watch Texas Country Reporter’s interview with Robert Bruno in 2008.

Judging from the unfinished building he left behind, it’s not clear whether Bruno ever seriously intended for his creation to function as a house. Its 2,200-feet-of-space interior—an estimated area, as nothing in the structure is square; Gunderson says Bruno would have found the whole notion of square footage “ludicrous”—was principally designed as sculpture, albeit with three bedrooms and two and a half baths. It features unusual angles and stained-glass windows, and the rough welds in the steel walls sometimes jut out, especially on the staircases and the uneven floor planes. By contrast, the kitchen and bathrooms look straight out of Home Depot; compared with the rest of the house, they are almost bizarrely conventional. Gunderson says Bruno finished them in such a way only for expediency. Had he lived longer, he would have likely attended to every sink and cabinet with the same handmade care he gave the few pieces of elegant furniture he built for the house.

In 2008, a few months after moving into the sci-fi animal he had made, Bruno died, at the age of 64, following a long battle with colon cancer. He left the building to his daughter (he and Patricia divorced in 2002) and his half of P&R to Martinez, who for years acted as a volunteer caretaker of the house until its sale this past fall. He would occasionally arrange for ad hoc tours, proud to show off this shrine to Bruno’s independent spirit.

One more thing about Corten steel: it lasts a long, long time. Left out in the elements, it forms a protective skin of rust that, critically, stops at the surface, preventing deeper rust and corrosion. Says the London-based artist Jeff McMillan, a Lubbock native and graduate of Texas Tech, “After the apocalypse, the Bruno House will still be there.”

But in what form? The real estate agent who was handling the Steel House listing was Courtney Bartosh, of the Bartosh Group at Taylor Reid Realty. She and her husband, Blake Bartosh, are the managers of Bartosh Realty Group LLC, which, according to Blake, purchased the home. Before taking the property off the market, Courtney, the 2020 Keller Williams Realty Lubbock rookie of the year, told Texas Monthly in early December that she planned to finish the house and offer it on a vacation rental site such as Airbnb or Vrbo if she didn’t find a buyer for $1.5 million. “We have contractors bidding it out,” she says.

Bruno had told friends of his detailed plans for the house, many of which were never realized—including installing a library inside one of its legs. Additionally, he intended to line the walls with plaster casts of nude torsos, a smooth counterpoint to the interior’s ribs of exposed steel. It’s unclear whether he would have followed through with these designs, but the new owners most likely won’t. Martinez and Gunderson say Courtney hasn’t consulted with them, although she says she received guidance from Christina Bruno. “It’s not going to be anywhere near what it used to be after they finish with it,” Martinez says. “The outside might stay the same, but the inside will not.”

However, Bruno’s friends do agree that something must be done about the house. For Bartosh to run a successful rental, she’d likely need to bring the place up to code, a daunting task that will doubtless necessitate changes to the interior. Some areas lack flooring, leaks have developed, and, at the time of the sale, plywood partitions still sat where Bruno left them.

Christina says she approached Texas Tech at one point about acquiring her father’s house but elicited no interest. Urs Peter Flueckiger, who in June became the interim dean of the architecture school, says that before he learned of the sale, he’d hoped to create a foundation for the Bruno house and use the space for lectures and visiting architects. Flueckiger, a friend of Bruno’s, says, “I cannot imagine he would have someone not educated in architecture or art putting in a curtain for the sake of renting it out. For me, it’s just heartbreaking to see this slipping through my hands like water through a sieve.” Martinez is similarly despondent: “Now it’s being treated like a motel, and I think that’s wrong, ethically wrong. If I was a millionaire and I had the money, of course I’d buy it. But it sure as hell wouldn’t be for an Airbnb.”

Courtney says she plans to follow Bruno’s wishes as much as she can, such as continuing to plaster the walls (a job he started but didn’t finish, she says). Renting the home will make it more accessible, she notes. “People love it; they just want to see the inside of it.” On the project’s Facebook page, entitled “Robert Bruno Steel House VRBO,” Bartosh has been documenting the changes through updates and videos, including from her TikTok account.

The Bartoshes insist that Christina’s claim that she sold her father’s home for $250,000 isn’t accurate, though they declined to reveal the actual figure. “I sold it at a low price,” Christina says. “[Courtney] said she wanted to turn it into a bed and breakfast . . . She did what she needed to do. I’m not upset.”

Nobody could have anticipated that a local realtor who never met Robert Bruno would be the one to bring closure to his life’s passion project. Yet, however unexpectedly, the Bruno house may finally be finished, almost half a century after its story began.

Rainey Knudson is an arts writer in Houston. She recently edited One Thing Well, a book about the Rice Gallery, and is now editing a book about Texas art since 2000.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Art

- Architecture

- Lubbock