In the mid-twentieth century, the Ukrainian tailor Nudie Cohn elevated the craft of suit-making to an art form. The rhinestone-studded western wear he produced at his North Hollywood shop, Nudie’s Rodeo Tailors, not only sparkled but also told stories. “Nudie” suits, as they came to be called, were embroidered with anything the wearer wanted, from covered wagons and saguaro cacti to pterodactyls and marijuana leaves. They were uniforms of self-expression, no two ever quite alike.

Johnny Cash wore them. So did Elvis. As did plenty of Texans, including Waco-born honky-tonk singer Hank Thompson, who donned airplanes, ducks, and Humpty Dumpty at his performances. “I really got the compliments on it Saturday night in Fort Worth,” he wrote Cohn after wearing one suit in 1964. Gene Watson and Audie Murphy were fans, as were ZZ Top, Sly Stone, and George Jones. Queen of the West Dale Evans even gave the eulogy at Cohn’s 1984 funeral, which didn’t mean the end of the Nudie suit craze. Today, the Austin-based clothing brand Fort Lonesome aims to “carry forth the torch of the Rodeo Tailor,” and Grapevine rapper Post Malone rocks Nudie-inspired getups embellished with barbed wire, pinup girls, and snakes.

“I love that the person who commissions the suit has an influence on it,” says Jane Reichle, the latest Texan enamored by this “wear-your-heart-on-your-sleeves fashion,” as she calls it.

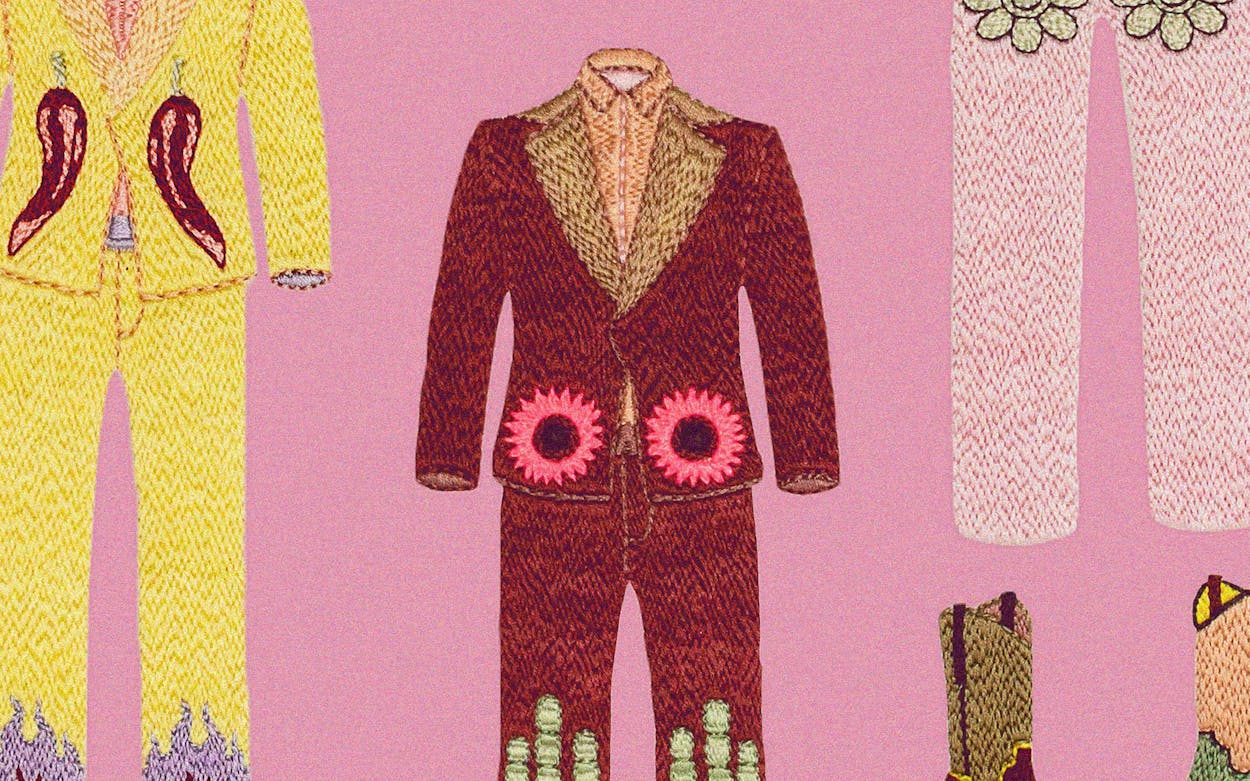

Reichle, 24, spends an inordinate amount of time hunched over a wooden hoop embroidering her own Nudie suits. Hers stand just fourteen inches tall, teeny enough to fit a chihuahua—if they weren’t two-dimensional. It takes up to fifty hours to create just one, which accounts for the $1,500 price tag—a bargain compared to the vintage garments themselves, which sell for tens of thousands of dollars. Reichle’s versions allow admirers to own a Nudie suit without needing to muster the guts to actually wear it in public, which helps explain why her latest collection, on view at Yard Dog through March 30, has nearly sold out.

“Not everyone thinks they can pull off eccentric clothing,” Reichle says. “People are more excited to hang fine art in their home than wear it out in public.”

It was Reichle’s grandmother Helen who gave Reichle her first box of embroidery floss in 2018. She loved the meticulousness of needle and thread but soon joined the teaching program Americorps, which left little time for crafting. Then, in 2020, the pandemic shut down the school near downtown Austin where she worked as a paraeducator. Inspired by the documentary Sisters With Transistors, which charts women’s entry into the electronic music scene of the 1970s, Reichle started embroidering motherboards onto a vintage jacket. After 170 hours of poking herself with an embroidery needle (Reichle counted), she realized she never wanted to stop.

Alas, being a textile artist isn’t a likely path for a kid from Westlake, the Lululemon enclave of Austin, where her family moved in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina flooded their New Orleans home. Reichle’s parents wanted her to have a stable, dependable career. The pressure made her gutsy. She cold-called galleries to show them her creations, which soon morphed from embroideries on three-dimensional clothing to embroideries of two-dimensional clothing, like haute couture for stylish cartoons.

Now, galleries call her. Embroidery is a seventy-hour-a-week gig. She’s booked for the year, with shows at Webb’s Fair and Square in Fort Davis and Neighborhood Store in Dallas. Kendra Scott even bought a couple of her embroideries for the company’s flagship store in Austin.

Reichle’s rapid success reflects the trendiness of embroidery, enjoying popularity on the runway (thanks to designers like Emily Adams Bode) and in galleries, where it’s elevated to the status of fine art. Feminist artists like Judy Chicago and Faith Ringgold pioneered its use in the 1970s. Others followed, though the field remains sparse compared to other art genres. “With painting, it’s really hard to break through because everything has been painted and it’s all been done,” Reichle says. “But with embroidery, you can come up with new concepts without copying other artists because there are so many unexplored areas.”

One square inch of embroidery takes up to an hour and a half to complete, but Reichle isn’t fazed. She’s been known to work in her apartment—perched at her desk, curled on the couch—for eighteen hours straight, a “hyper-focused flow” she credits to her ADHD. The tools of her trade are simple: a small embroidery hoop, needle, and about one hundred different colors of floss. Each comes with six strands that Reichle splits down to one or two threads for near-microscopic detail. She doesn’t use a magnifying glass. Nor a thimble, which is cumbersome and best left for Monopoly. “Skin is regenerative,” she says, though that doesn’t help her back, which aches. Every ten days or so, she emerges for a much-needed lunch with friends or a backyard bonfire—but the work often follows her. “I have a hard time not talking about art when I’m with people,” she says.

Fashion and music inspire her work, and Nudie suits have a pant leg in each, making them a natural subject. She first included one among a collection of embroideries of clothing she exhibited in Dallas last year. The gallery asked if she’d create an entire series, so she made eight more, and they sold out within a month. Reichle doesn’t reference historical Nudie suits but invents her own. She decorates them with simple designs that evoke tattoos: butterflies and flames, pinup girls and lightning bolts, daisies and cayenne peppers. It’s sugar and spice in happy hues she likes to think would have delighted Nudie Cohn.

“I like cheerful art, I really do,” Reichle says. “I don’t create from a place of pain, but more from a place of what I love about the world.”

If she can find the time, she’d like to make an actual suit to wear at gallery openings. She’s still considering what she’ll embroider on it.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Art

- Fashion