This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Todd Oldham’s SoHo showroom perfectly fits the man who’s become fashion’s court jester—it’s loud, gay, and chaotic, just like his clothes. There’s rap on the sound system and, as part of the fall 1994 collection looping on video, Cindy Crawford’s gleefully unfettered breasts, bouncing over and over and over in a low-cut, tie-dyed, snowflake-dotted gown. The actual collection hangs nearby, typically overstated Todd-wear that includes evening dresses shimmering with beaded spiderwebs, tiger-striped plastic raincoats, pin-striped jackets cropped just below the bust, and flirtatious suits woven from brilliantly colored ribbons. A gilded crystal chandelier laden with extra prisms and fringe twinkles precariously over a conference table; newspaper clippings from around the world serve as wallpaper, evidence of the Texas-born designer’s global commitment as well as his global ambitions. “I wanna bring you joy/I wanna bring you joy/I wanna bring you joy, joy, joy …” floats like a chant from the stereo speakers.

This more-is-more ruckus seems to inspire, rather than distract, the sharply suited men and women sitting around the conference table this late afternoon. They, too, want more, and they want it from Todd. Specifically, they are from a cable-TV network, and they want Todd to create a home-shopping show for them.

They’ve had to get in line: Though very few workplaces in America would truly welcome or understand a Todd Oldham suit, this has been Todd Oldham’s year, one in which his clothes have been given major play in every major fashion magazine. Even more important, he’s the only designer to have a regular gig on MTV, which has exposed his taste to around four million people—including men and boys who are not regular readers of, say, W. Julia Roberts showed up at a preview of his last collection. Rosie O’Donnell landed on the worst-dressed list after wearing too much Todd. He was delighted.

Todd is moving into film, directing videos and costuming stars such as Wesley Snipes, who will play a transvestite in an upcoming Steven Spielberg production. His couture line, priced in the four figures, is sold at Neiman’s and Bergdorf’s. His less expensive line, Times Seven, is thriving; his shoe line and obligatory—not to mention potentially lucrative—fragrance are in production. He’s making clothes for sale on MTV, and his very own boutique opens this month in SoHo. Even the tabloids have jumped on Todd’s bandwagon. Last January the Globe featured his clothes in a spread headlined DON’T LAUGH! THESE FREAKY DESIGNER DUDS COULD END UP IN YOUR CLOSET! Forget the cool grace of Richard Tyler, the impeccable tailoring of Isaac Mizrahi, the sensual elegance of Calvin Klein. Forget practicality. Todd makes clothes that are magical, not practical, and that is why one of America’s most esoteric and expensive designers has become the darling of the audience least able to afford him.

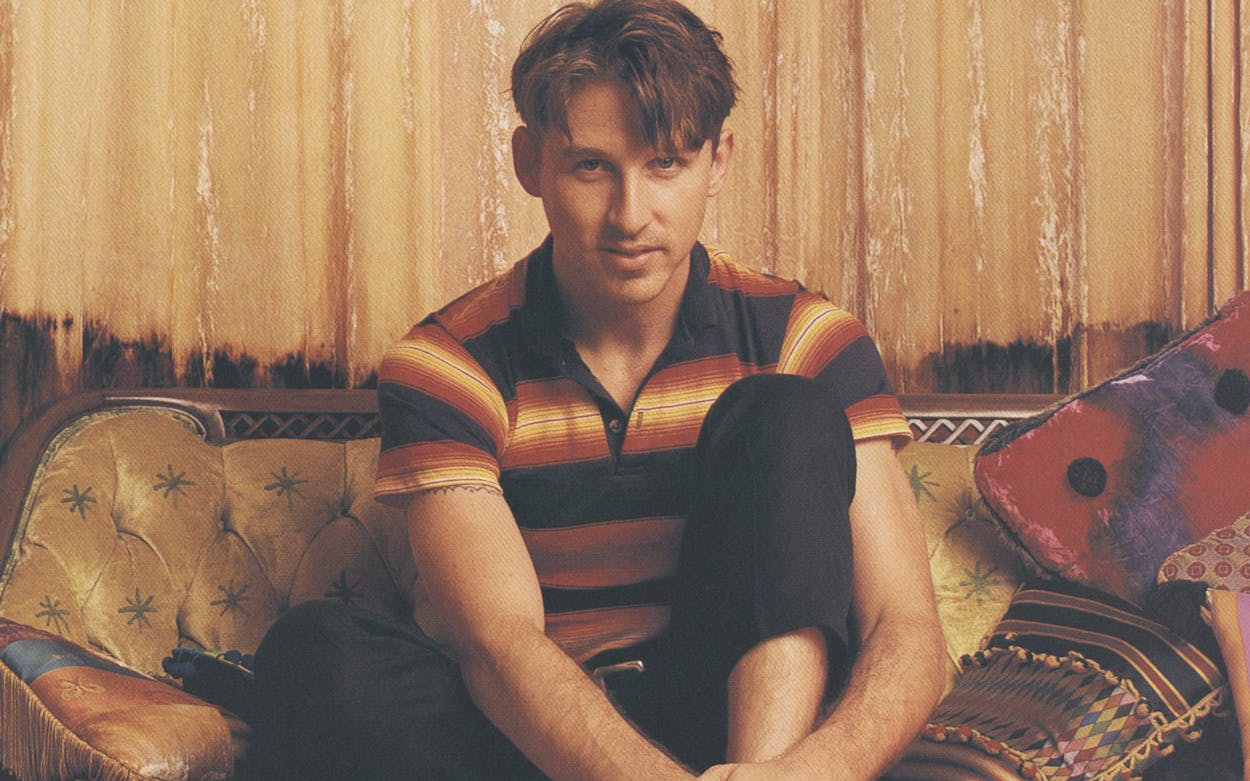

Hence the suits at the table. Ever since he made it big last season with his clever “Todd Time” segments on MTV’s House of Style—Todd showing viewers how to decorate their dorm rooms with items priced at $1.98 or make summer sandals by cutting the toes out of combat boots—almost every home-shopping exec has come calling, desperate to sandwich Todd between the cubic zirconia and the thigh creams. Today’s supplicants hope to market items that would give American homes Todd’s signature look, a kind of witty but politically correct retro-eroticism—home decoration as a collaboration between I Dream of Jeannie’s Jeannie, Murphy Brown, and the Happy Hooker. Sitting near the end of the table, Todd, 32, listens to the execs gamely. Also at the table is Tony Longoria, 40, the deeply sideburned, gently persuasive man who has been Todd’s partner in life and work almost since the two met in Dallas in the mid-eighties.

With his eternally youthful features and thrift-shop ensembles, Todd looks as out of place in this group as Beaver Cleaver at a business meeting in Milan. Even so, it takes him only a few seconds to divert the executives’ fairly pedestrian ideas toward something more, well, Todd-like.

“What about pajamas?” someone at the table suggests.

“Pajamas would be great!” chirps another, nodding and bobbing in his seat.

“Men’s pajamas!” Todd announces, springing out of his chair and bounding back with a synthetic fabric he developed, printed with a fall landscape evocative of the backgrounds in Sears photo portraits.

“Great!” choruses the table, with more nods and bobs all around.

“And make ’em big!” Todd says, grinning.

“Great!” the executives agree.

The talk turns to the rhinestone-spangled dog collars Todd designed for one of his favorite causes, an organization that cares for the pets of people with AIDS. “My dog ate a charm and pooped it out and it still survives,” one exec says, chuckling.

Todd blinks, apologizes, and then thanks the man for his continued support of the organization.

“Tabletop?” someone interjects, anxious to move on.

“Can do!” reply Todd and Tony.

“Clocks?”

“We can do that easy!”

“Flatware? Towels? Placemats? Tablecloths? Soap on a rope?”

“Yes!”

“Shower curtains?”

“Have you seen the one in my studio?” Todd says. “It’s Donna Reed in Morocco!”

“Jell-O molds?”

A cloud darkens Todd’s typically sunny face. “I don’t want to do anything to encourage eating that crap,” he says.

“A toaster-oven cover!” someone blurts, speeding onward.

“Tea cozies!” volleys Todd, good humor restored.

“A refrigerator cover—with Velcro in front!” another exclaims, delirious.

“We could do it in harvest gold!” Todd declares. The room explodes in giggles, but you can see they’re ready to go with it. Because in the world of Todd Oldham, the goof is always gold.

A few hours later, a waitress at Lupe’s Mexican restaurant in SoHo sets a plate of black beans and rice in front of Todd and an identical plate in front of Tony. As the two begin to eat what Todd, a vegetarian, describes as “the most nutritionally complete meal,” the designer expounds on his sensibility.

“Americans have a big problem with sex,” he insists. “So everything I do is sexy, but in an approachable way. I do quirky sexuality. The top of your butt is very sexy, the bottom half of the bust, the side. The least obvious things are far more sexy—the spring show was based on dreams, so we showed a lot of panties.” Quirky sex (the panties in question weren’t the assertive high-cut bikinis popular today but the demure bottom-shrouding briefs of the sixties) and rigid nutrition may not usually go hand in hand, but they seem perfectly compatible in Todd’s world—where, sooner or later, everything matches. Something about Todd’s antic clothing, open face, and fawning press clips conjures an image of boyish not-quite-thereness, of a fashion savant whose success is somehow accidental. In fact, Todd has been portrayed as fashion’s good boy for so long—his favorite adjective really is “nice,” the same word fashion types often use to describe him—that the assured sound of his voice and the determined look that further hones his broad, high cheekbones can come as something of a shock. No one is more serious about making fun than Todd.

His success is more about Todd the personality than Todd the designer. True, his timing has been flawless: The crash of the go-go eighties and the spread of AIDS resulted in years of fashion at its most monastic, with the palette and the cut of clothing on both sides of the Atlantic tending to be somber and severe. No wonder the fashion press loves Todd, along with other humorous designers like Anna Sui, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Franco Moschino; Todd’s floor-length Fair Isle sweaters and multiple-monogram divorce shirts make them laugh. But he doesn’t seem to want what other designers want—namely, exclusivity. He doesn’t seem determined to use his clothes to convey status. He even uses video to teach customers how to copy his ideas: On one House of Style segment, Todd rummaged beneath some grimy thrift-shop racks to show viewers where the most tenacious shoppers hide their treasures. You can buy the clothes or you can buy the look—either way, Todd comes out okay.

In fact, when fashion types talk about Todd, they talk about the Package, the way he has shrewdly used contemporary concerns to further his career and his vision. He has attracted the right clients: The names, including Susan Sarandon, Madonna, and Candice Bergen, read like a list of America’s most politically correct. His devotion to the causes of the age—AIDS, homelessness, and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals—has helped ingratiate him with like-minded New York fashion editors. He is telegenic: “He’s very accessible, even though he’s got a sort of warped view of the world,” says House of Style producer Alisa Bellettini. He has embraced multiculturalism and globalism with a vengeance, in his markets as well as his designs. (Oldham’s clothes sell out in the Middle East, where the world’s richest women wear his gaudiest gowns under their chadors.) His work appeals to a broad spectrum of ages—baby boomers and their progeny—and, perhaps more important, to both sexes of whatever sexual preference. Along with supermodels like Cindy Crawford, Veronica Webb, Christy Turlington, and Kate Moss, transvestites like RuPaul and Billy Beyond star in Todd’s shows. Everyone, it seems, wants to be in on the joke.

“I did some school uniforms in Japan,” Todd continues, still working on his beans and his theme of fashion as liberation. In that conformist country, kids were choosing their schools not for the academic program but for the style of the uniform; some shrewd administrator, seeking an edge, went to Todd. The designer was shown an elaborate foldout of color choices—all navy blue. “Too many rules,” Todd thought at the time. “But we shook ’em loose—we changed the buttons. And then we put pleats in the back,” Todd says, grinning slyly and wiggling his fingers wickedly. “We slid by.” Todd’s goal could be defined as loosening up the entire world, inch by inch. Without ever giving one himself. Most designers sell one concept on the runway and then, working with retailers, amend it for the real world. Not Todd. “Basically, we set up the business to appeal to about three people,” he says. “We sacrificed a lot of financial success for creative success.” It isn’t that Todd didn’t want to be famous—he just wanted it on his terms.

He grew up in the North Texas town of Keller, in a home that clearly set the pattern for the life he lives now. His mother, Linda, from Hereford, imparted a good deal of horse sense to her four children while encouraging creativity. Chores were not gender-specific, and neither was playtime; when Todd showed a penchant for sewing (he made his sister an op art dress from two pillowcases when he was nine), no one told him boys didn’t do that. “We wanted our children to be able to function and take care of themselves in the world,” Linda Oldham drawls. “We taught the kids, ‘Don’t be mean, and if you’re worried about something, you should go fix it.’ ”

When Todd was twelve, his father, Jack, a computer consultant, moved the family to the Middle East, an experience that inspired Todd’s passion for color and texture. Four years later Todd returned to Keller High School, and the day after graduation he set out on his own.

The year was 1980 and Todd was eighteen. He headed for Dallas, which was in the midst of the oil boom and pleased with itself in a way it had not been before and probably never would be again. It has become part of the Todd Oldham legend that, after being fired from the alterations department of the Polo shop—“He didn’t quite conform to the ideas they were trying to promote,” his mother says—he borrowed $100 from his parents, dyed some fabric in his bathtub, and sold his first ensembles to Neiman’s. Shortly thereafter, he became to young, hip Dallas what Victor Costa was to the city’s flashy middle-aged millionaires—the arbiter of style.

Even then, Todd understood the importance of the Package: He partied at the Starck Club; collaborated with the artist of the moment, Dan Rizzie; became famous for his addiction to I Love Lucy reruns; and allowed his apartment, with its collection of Mexican folk art and sixties paint-by-number paintings, to be photographed for the trendy Texas Homes magazine. Still, the business maintained its eccentric, aw-shucks character. Family members ran the new Dallas factory—Todd’s grandmother even cooked lunch—and until 1985, when Tony Longoria left his job buying from young, hip designers for Neiman’s, Todd served as his own sales rep. He pushed things like belts made of crushed bottle caps. “Todd was the person showing you the line,” says Craig Lidji, who in the early eighties worked at Lou Lattimore, his family’s store. “He had a knack for amusing you, for making it fun.” Taking on New York didn’t seem a necessary part of the program. When Todd first showed his clothes in Manhattan, Women’s Wear Daily dismissed him as a Gaultier wannabe.

But then the boom became the bust, and as backers disappeared and bankruptcies loomed, Todd’s protestations that he would never leave Dallas grew fainter. In 1988 Todd and Tony moved to New York to give the business one more chance; within a year, Todd was no longer thinking about abandoning fashion for film school. He founded Times Seven, got his clothes into Bergdorf’s and Saks, and perhaps most important, he won distribution agreements with a big Japanese concern, Onward Kashiyama, in 1989. Finally, Todd could design the lavish but lighthearted clothes he’d always imagined. Stardom followed, bringing with it fashion spreads in everything from Vogue to Le Figaro and the obligatory Gap ad, which portrayed a new, smolderingly sexy Todd. “We made a conscious decision to do only what we love,” says Tony. “I for one feel that’s why we’re still around. We carved our own place in the market.”

After dinner, Todd and Tony begin the hike to their apartment uptown. Being a star has its drawbacks—“You’d be amazed at the power of that show,” Todd says of House of Style—and so he has developed the brisk, head-down stride of the I-do-not-wish-to-be-recognized. It doesn’t work. When he pauses outside a chic Greenwich Village trattoria, the well-dressed New Yorkers dining alfresco snap to attention, as if they have picked up a familiar scent. The name Todd Oldham, Todd Oldham, Todd Oldham flutters through the crowd, growing louder and stronger the longer he lingers. They are grateful and eager and hungry for more.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- Fashion