This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

At a time when most of the fabrics we use originate in oil wells and test tubes and are decorated with tender loving care on the printing press, it is a refreshing anomaly to find that traditional, dyed-in-the-wool textile artists still exist.

Thanks to the craft renaissance of the last generation, fabric handiwork of all kinds has flourished in spite of competition from the assembly line; weaving and needlework in particular have attained a high profile. Slightly less publicized is a group of fabric decoration techniques—painting, printing, dyeing—usually called surface design.

The term has a technical ring, but its practitioners are legion. If every happy homemaker who ever made a ladybug batik and every hippie who once tie-dyed a T-shirt were laid end to end, they would reach from Kerrville to Katmandu. The issue here is not scope but skill, and that is where four Texas textile artists come in.

John Larcade, Rebecca Munro, Mary Murchison, and Fred Weyrich don’t do anything that thousands of other textile workers haven’t done (well, maybe Fred does), but they differ from the rest because they do it better. The techniques they use are ancient and for the most part Eastern (textile surface decoration is believed to have originated in India and Egypt), but their vision is fresh and experimental.

As impressive as the variety of their work is its finesse; you’re as likely to see one of their creations being worn to a party as hanging in a gallery. And that only goes to show how rare is the commodity they all produce: art with a practical side.

If It Doesn’t Move, Paint It

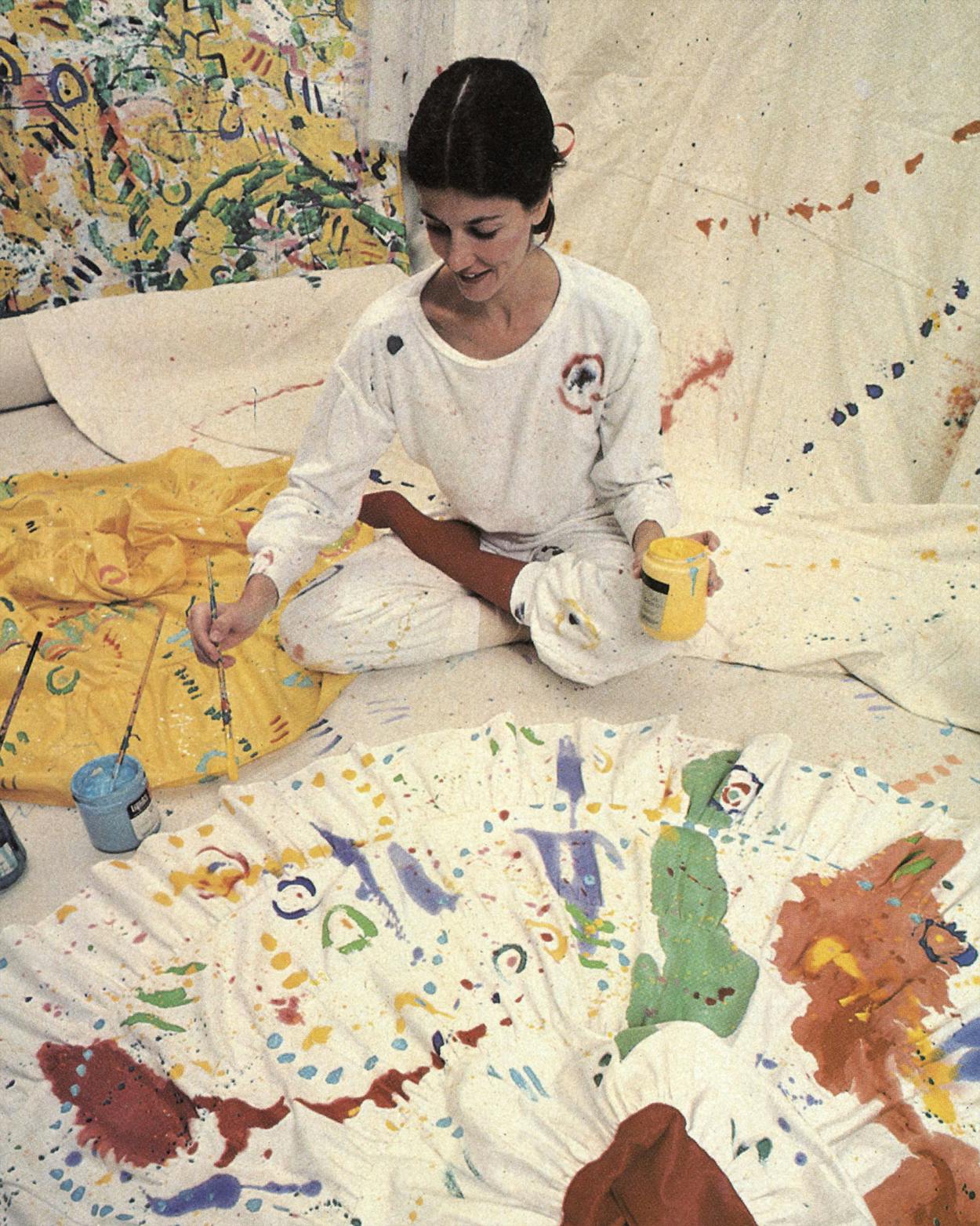

Canvases line the walls of Mary Murchison’s small Dallas studio, a converted garage where the artist rolls out bolts of fabric, sits on the floor, and paints, while her two children and four Boston terriers watch from a safe distance. In the past Murchison worked mostly on conventional canvases, but nowadays she paints walls, furniture, pillows, and clothing as well. Her art is as whimsical as she is.

“What I like to do best is to paint,” she says. “I’ve been doing it since I was twelve. Give me a surface and I’ll paint it.”

Her style is spontaneous, her attitude amused. Once, while moving a freshly painted dress, she accidentally smudged the bodice. With only a moment’s hesitation, she dipped her brush into a can of paint and spattered a liberal amount over the blemish.

Her experimentation with pillows and upholstery fabric came about at the suggestion of an interior designer, but dresses are her main interest at the moment. She designs them herself, laying out the pattern, choosing and painting the fabric.

Murchison’s drawings and canvases are available through the Contemporary Gallery in Dallas. Edmund Kirk Associates in Dallas handles her upholstery fabric and pillows. Her dresses are available in specialty clothing shops, and John Robinson of BPR Group Designers represents her line at the Dallas Apparel Mart.

Man of the Cloth

With most art, one can easily tell where the work begins and ends. It’s a painted canvas, a sculpture, or an assemblage; it has a top, a bottom, and sides.

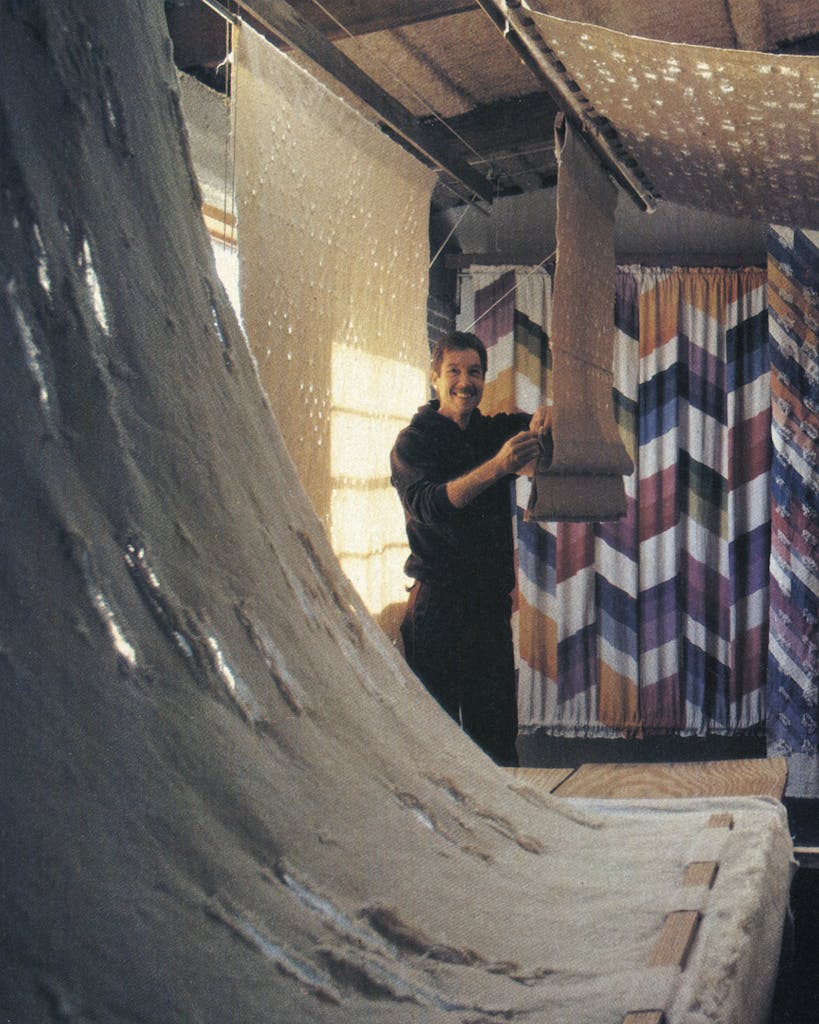

But Fred Weyrich’s fabric art is different. It encompasses entire rooms and the work itself is only the nucleus, the pearl in the oyster.

Weyrich dyes and cuts his fabric; he unravels it to make fringe. Then, by arranging panels in different ways—at angles, in varying lengths, in undulating lines—he alters the space in which they exist. The placement of the fabric creates a sense of movement and rhythm. Space and light are not incidental to his art—they become part of it.

Since leaving Yale University, the Austin artist has sought to free his work from stretched canvas’s limitations of static surface and rigid outline. Today he still uses canvas because, as he says, “it’s practical, functional, and washable,” but he seldom nails it to a framework.

Besides his room-size pierced canvases, Weyrich makes functional pieces such as screens and window shades and also spray-paints and silk-screens canvas for upholstery. When not working on his own projects, he teaches basic design and color at Austin’s Laguna Gloria Art Museum.

Weyrich’s large pieces are available through Objects Gallery in San Antonio; the functional work is available through the artist in Austin.

Finger Prints

Among Rebecca Munro’s textile-printing implements are a Korean cookie press, a tobacco mold, and several Javanese tjaps (metal batik printing blocks). Her work is as unusual as her tool collection, and although she employs ancient decorative techniques, the overall effect of her abstract patterns is quite modern.

Munro seldom stops at one process. Fine cottons and linens, silks, and canvas provide the background for colors that she applies in layers to achieve a three-dimensional effect. “I’m interested in depth,” she says, “so there is a lot of implied textural surface in my fabrics.” She employs painting, printing with wood blocks (many of which she carves herself), and paste- and wax-resist (in which a waterproof substance is applied to the fabric to prevent the dye from taking in certain areas).

The UT graduate teaches textile design at Laguna Gloria Museum and works at her Austin home, where in good weather she spreads lengths of freshly dyed cloth on the driveway to dry. She wants her art to be functional. “These are paintings you can wash,” she says.

Rebecca’s work includes large architectural canvases and art panels, but most of her clients are interior designers. Her studies for fabric designs are shown at Objects Gallery in San Antonio and her decorative fabrics at Hilines in Dallas.

Fit to Be Dyed

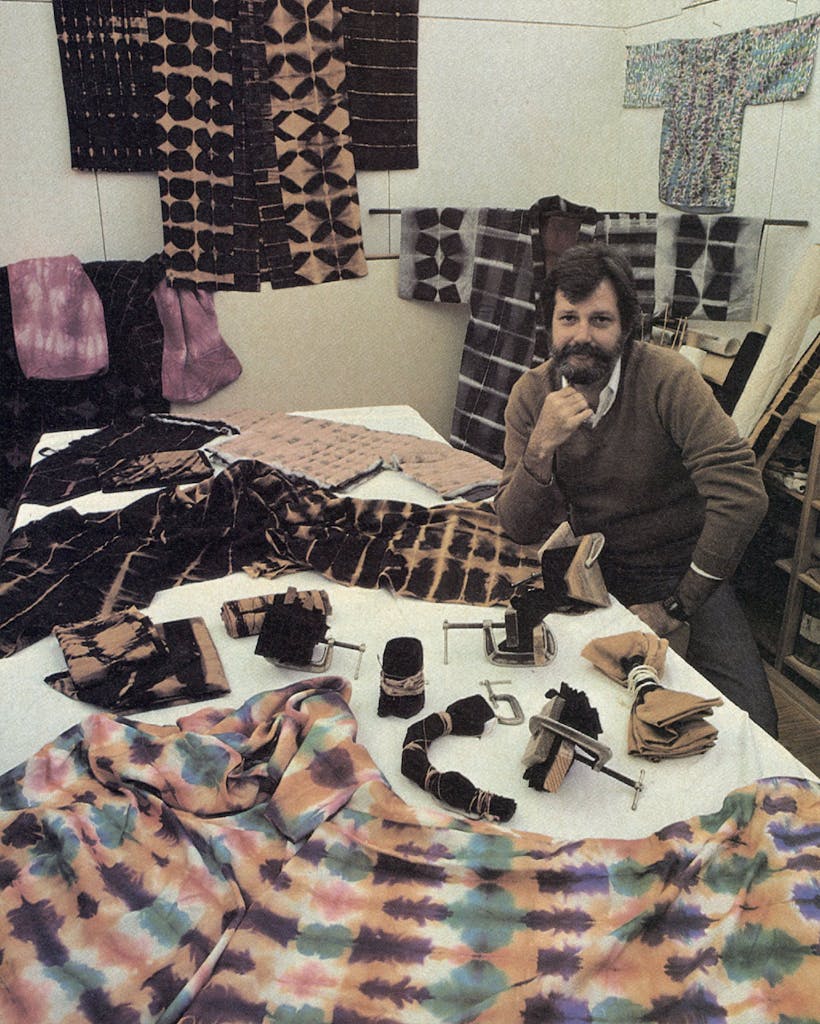

John Larcade works with kimonos, but his interest in fabrics started in Mexico. Seeking relief from a demanding job, he took some time off to attend art school in San Miguel de Allende, where he learned to print and dye fabric. What began as occupational therapy has turned into an avocation.

Larcade, a partner in the architectural firm of Lance, Larcade & Bechtol as well as a lecturer at the University of Texas at San Antonio, uses the ancient methods of batik and plangi. Batik involves a wax-resist technique. In plangi, the fabric is folded, clamped, or tied, and the resulting pressure points resist the dye.

(Anyone who has ever tie-dyed a T-shirt will appreciate John’s skill with plangi.) Sometimes he turns the process around, dyeing the material first, then tying and bleaching it to achieve a reverse effect. To create intense colors, especially in silks, he dyes the fabric several times in succession.

Larcade works on kimonos because the simple, unconstructed shape shows off pattern and color well and also lends itself to experimentation. Sometimes he puts different patterns on the front and the back. Though his garments can be worn with striking effect, he regards them mainly as wall hangings.

The kimonos may be purchased at Objects Gallery in San Antonio.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Art

- TM Classics

- Crafting