This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

A very good thing, the sun. Without it many of life’s enrichments would simply cease to exist, including afternoon football, stained-glass windows, Yankee tourist dollars, and virtually all forms of vegetation. Without it Houston’s mildew problem would certainly become completely unmanageable.

But like all good things, the sun must be taken in moderation. And in Texas, where certain areas are blessed with 299 days of sunshine a year, turning flat West Texas plains into great sandy griddles and cities into saunas, we learned long ago to appreciate the absence of sun—or, as we fondly call it, shade.

Texans seek shade the way residents of less fortunate climes seek the sun. Surely it was a denizen of some dank Eastern urban thicket who suggested we direct our feet to the sunny side of the street. In most Texas towns there is no sunny side of the street: both sides are covered by accommodating awnings.

If seeking shade is a major goal of Texas life, providing it is an industrial conglomerate that incorporates engineering, manufacturing, construction, and agriculture. Let us examine some of the options available when our good friend and constant companion the sun overstays his welcome.

Portable Shade #1: Headborne

Derived from the familiar sugar-loaf sombrero, the ever-popular ten-gallon hat was the cowboy’s second-best friend. Its current use is often primarily decorative and metaphorical (see Strait, George). The James Dean skinny-brim had its moment in the sun, but it was soon replaced by the ubiquitous gimme cap and sun visor, which keep our noses, if not our necks, from turning red. Meanwhile, pioneer women wore sunbonnets to shade their faces.

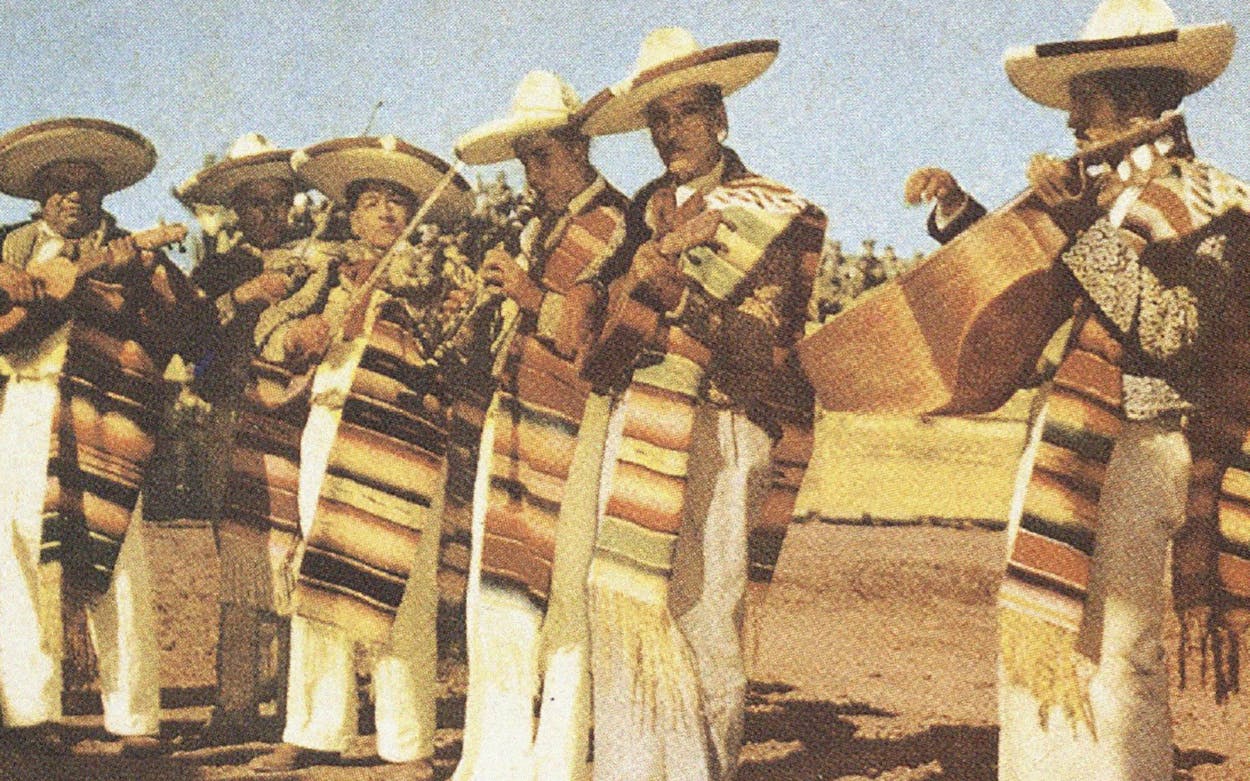

A Welcome Visitor From the South

Hey, Cisco! Hey, Pancho! Hey, sombrero, from the Spanish “sombra,” meaning “shade.” In 1823 James Austin requested a “Spanish, wide-brim, white, wool hat” from his brother Stephen, because he understood they were “very cheap and it will be almost impossible to stand the prairie without one.” The abridged version in gaily colored straw (left) enjoyed a mercifully brief period of favor in the fifties.

Portable Shade #2: Hand-Carried

Its proper name is “parasol,” if you please, and not “umbrella” (that’s parapluie, n’est-ce pas?). Rent one, complete with a pair of matching beach chairs, for the whole day on Galveston’s Stewart Beach for $5.

Certainly not portable but able to shelter small crowds beneath its capacious thirteen-square-foot wingspan is this Sunfast acrylic beauty (below) from Santa Barbara Designs, available through designers at E. C. Dicken in Houston and Dallas. They’ll throw in the teak pole, frame, and finial for a cool $3,925.

Portable Shade #3: Automotive

Ranchers and farmers learned this trick quickly—probably from their cows, which seem able to find shade anywhere. The trick, of course, is to keep the truck between you and the sun. But it’s okay to squint anyway.

Out Under a Limb

There is something ineffably soothing about natural shade, the kind of cool stillness found beneath the limbs of a glorious old shade tree. Regional plant authority Lynn Lowry is nuts for the sugar maple (below), preferably grown from native East Texas seeds instead of the more common northeastern ones. He also suggests the swamp chestnut oak for East Texans and the bur oak for the arboreally less fortunate. Says Lowry: “I don’t know of any other tree that will grow in all parts of the state.”

A Porch by Any Other Name

Architectural historians have noted that from dogtrots to Victorian wraparound verandahs, porches have reflected the national character—expansive, pragmatic, and informal. In the fifties we moved indoors, into the air conditioning, and the once-grand porte cochere became the carport. Gracious porches, like this one (above) on the King Ranch, have lost some of their popularity but none of their allure: They still bring solace to body and soul.

Colonnade in the Shade

This 150-foot grape arbor at San Antonio’s La Villita is but a particularly splendid example of a common method by which early Spanish builders provided shade. Dallas’ Frank Welch, long a proponent of vernacular architecture, borrowed the idea for this covered walkway at Kerrville’s Riverhill Country Club (top).

A Roof Over Our Heads

The freestanding pavilion has roots in the brush arbor (right), an ad hoc affair that was improvised for revival meetings and the like. Swimmers at Houston’s Southside Place Bath House can thank Taft Architects for the jaunty version below.

Gimme Shelter

In many parts of the state, the Texas highway department’s rest stops are much-needed oases of shade. Not content merely to provide welcome relief from the sun, those zanies at the highway department thrust themselves into the vanguard of the post-modern movement by sprinkling the landscape with culturally resonant and amusing folies. See the tepees off Interstate 10 near Sierra Blanca; dine beneath the faux derricks near Tyler.

Under the Cover

Remember when every Main Street in Texas extended awnings (far left) to welcome prospective shoppers and idle strollers from the scorching heat? Nowadays spiffy new designer awnings on storefronts, like these smart black numbers at Houston’s River Oaks Shopping Center (near left), carry a different message—yet another strip-center facelift. Just as before, the awnings are there to let us know everything is cool inside.

Jerry Jeanmard is a Houston designer.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Weather

- TM Classics