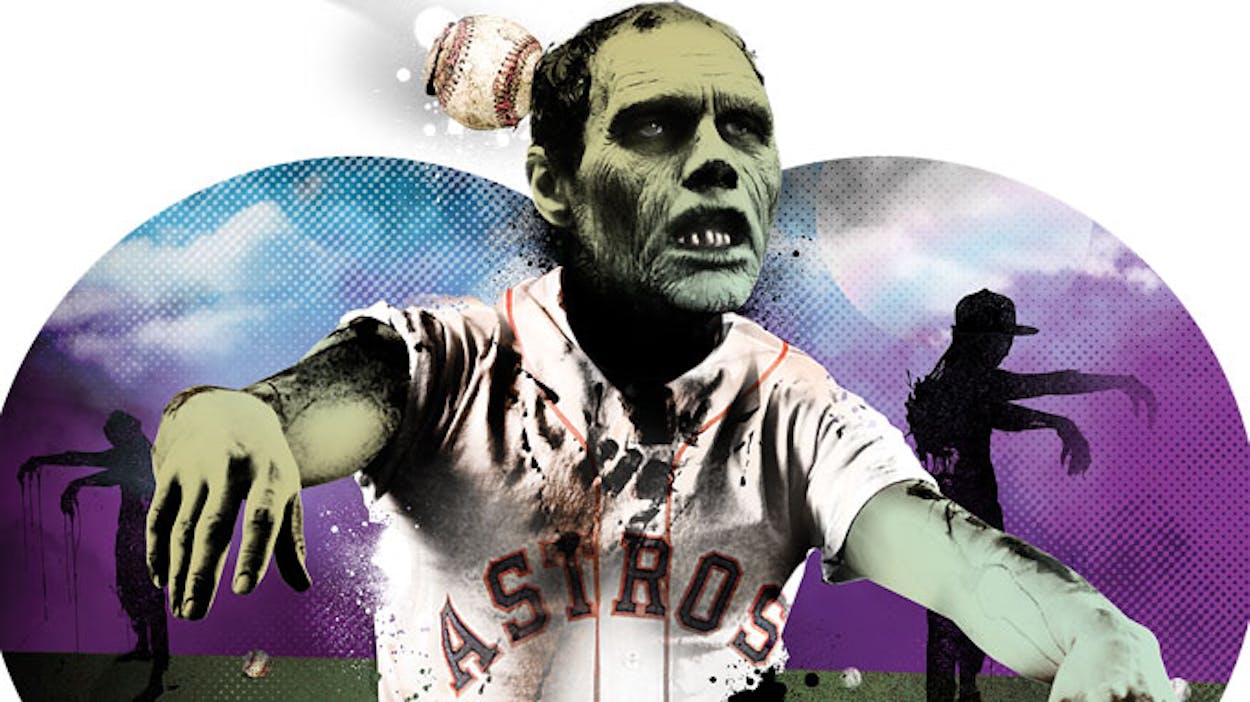

1. The Balking Dead

The Houston Astros’ recent move to the American League, after fifty years in the National League, still stings. They’ll now be forced to play the far superior Texas Rangers during the regular season, and they couldn’t even get Lance Berkman to come back and be their designated hitter. Instead, he signed with another team in the same division. The Rangers.

But right now, no one really cares all that much about the Astros-Rangers rivalry. What people want to know is if the Astros can make history—by losing more games than any baseball team in the modern era. They’re definitely on track—they lost 106 games in 2011 and 107 games last year. With new owner Jim Crane and new general manager Jeff Luhnow paring down the roster to youngsters and no-names, things could get even worse. The team will have an expected payroll of around $20 million—a paltry sum that’s less than the individual salaries of at least a dozen Major League stars. These Astros could lose 119 games, like the 2003 Detroit Tigers, or even 120, the contemporary record set by the 1962 New York Mets.

And that might be fine with Crane and Luhnow. Having the worst season in baseball history would, in a sense, be the best thing that could happen to the Astros, because the team’s real priority is to get the number one overall draft pick and the highest possible signing budget next season. Not for nothing was new manager Bo Porter hired from the Washington Nationals, which endured six years of misery to stockpile the young talent that helped the team get to the playoffs last year. Maybe Porter will be around long enough to see that happen. After all, three years after losing 119 games, the Tigers made it to the World Series. —Jason Cohen

2. The One-Question Interview: Ricardo C. Ainslie

A native of Mexico City who moved to the United States when he was seventeen, psychologist-psychoanalyst Ricardo C. Ainslie has always followed the news in the country of his birth. When the drug-cartel wars heated up in 2008, he decided to devote much of the next few years to traveling across the border and researching what was happening to the city of Juárez, ground zero for the horrific violence that has scarred Mexico. Ainslie, who lives in Austin and teaches at the University of Texas, took a dozen or so trips to Juárez and gained the trust of sources high and low (including numerous government officials and the mistress of one mid-level narco) to produce The Fight to Save Juárez: Life in the Heart of Mexico’s Drug War (UT Press).

Q: What attitudes about the drug war that you had going into this project were overturned by your reporting?

A: Like everybody in the U.S., my assumption was that there was a high degree of corruption at all levels of government. And of course that’s partly true; in the seven or eight states where the cartels control things, they control everything. The idea that there could be individuals who were trying to do the right thing was something I had not been prepared for. So one of the surprises for me was the mayor of Juárez at the time, a man named José Reyes Ferriz. My assumption—my prejudice—was that this guy was probably in bed with the Juárez cartel. How else do you get elected mayor of Juárez? But over the course of a year and a half, I developed the conviction that not only was this man not in bed with the cartel, but he had actually put his life in considerable peril in his efforts to deal with the cartel. He became one of the good characters in the story. Though he’s not a man without flaws.

3. Goodnight to You

The weathered granite marker outside the sprawling folk-Victorian home says it all: “Charles and Mary Ann (Dyer) Goodnight: Together they conquered a new land and performed a duty to man and to God.” The “new land” was the Panhandle, where the couple built the region’s first permanent cattle ranch, in 1876. On April 13 visitors can celebrate that legacy with the public opening of the Charles Goodnight Historical Center, which includes a visitors center and the couple’s restored home on the grounds of the old Goodnight Buffalo Ranch, forty miles southeast of Amarillo. “This was the first home in this part of the Panhandle,” says Montie Goodin, the chair of the board of the Armstrong County Museum. “It looked as if it had risen up out of the prairie. Back then there wasn’t a fence, there wasn’t a road, there wasn’t even a tree.” There were, however, buffalo, which the Goodnights practically saved from extinction in Palo Duro Canyon. Today, in a nearby pasture, ten head descended from the famed Southern herd graze quietly, just as their ancestors did when Goodnight himself kept watch over the ranch. The colonel would approve. —Brian D. Sweany

4. Come Back, Shane!

Fortunes rise: in 2004 former Dallas software engineer Shane Carruth won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance for a micro-budgeted time-travel thriller called Primer, and Texas seemed to have found its next great filmmaking hope.

Fortunes fall: for much of the decade that followed, Carruth plunged down the Hollywood rabbit hole, trying to secure financing for a sci-fi epic that ultimately never got made.

Fortunes take an unexpected left turn: this month, Carruth returns with the Dallas-shot Upstream Color, which he wrote, directed, produced, co-edited, and co-stars in and which is among the most singularly weird and transporting visions ever brought to the screen. The story centers on a woman (Amy Seimetz) who is drugged and kidnapped, then tries to understand what happened to her—a mystery that involves orchid thieves, a passel of adorable pigs, and a Philip Glass–like composer (Andrew Sensenig) who uses others’ misery as his inspiration. Ambitious doesn’t even begin to describe it: gorgeous images dance before our eyes in seemingly haphazard fashion (Carruth did the cinematography too), and for long stretches there’s no dialogue, only the driving force of the dreamy, synthesizer-heavy score (yes, he also composed the music). Like 2001, Blue Velvet, and Donnie Darko before it, Upstream Color seems destined to inspire a generation of college students to debate its meaning long into the night. A lot of filmmakers talk the indie talk while secretly hoping for a three-picture deal with Paramount; Carruth—who is distributing the movie himself, in limited theatrical release and video-on-demand—has emerged as a kind of one-man dream factory. Who needs Hollywood when you have imagination to burn? —Christopher Kelly

5. Dad Rock

The Dripping Springs–based singer-songwriter Sam Beam, a.k.a. Iron and Wine, first made his name as a breathy and brainy folkie. But when he tried to emulate the seventies pop recordings that he admired, his albums became something else entirely: amalgams of double-tracked vocals and dense jazz, rock, and funk arrangements. The fascinating yet scattershot Kiss Each Other Clean (2011) marked the epitome of this kitchen-sink approach. Ghost on Ghost, his fifth album—and his first for the prestigious Nonesuch label—jettisons the excess, and the results are near perfect: a less cluttered, slickly produced record that puts the emphasis back on Beam’s allegorical musings. And it’s obvious that the 38-year-old father of five is coping with the conflicting demands of adulthood. The album opener, “Caught in the Briars,” is a cautionary tale of life’s temptations, wrapped in Beam’s pseudo-religious wordplay. “Low Light Buddy of Mine” seems creepily insincere, while “Lover’s Revolution” is just the opposite, a jazz-propelled ode to family life. If Beam’s music is finally coming more into focus, it may be because his subject matter is too. —Jeff McCord