One of the great rock and roll singers stood on the stage with his arms crossed. He uncrossed them and crossed them again. He yawned. Then he sang a verse of one of his songs, “Don’t Slander Me.” His once mighty voice was thin and couldn’t quite reach all the notes. He turned his back on the audience between verses. He looked beat. It was 1993, and Roky Erickson and his backing band were performing at the Austin Music Awards. When they played his biggest song, “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” a piece of proto-punk rock that had once been an anthem of mid-sixties teen attitude, it sounded like a rehearsal for retirement. Roky, with his long black hair and thick beard, didn’t look happy. He wasn’t. He was a diagnosed schizophrenic who hadn’t taken any anti-psychotic medicine in several years and who would go home that night to a house where he kept half a dozen radios, TVs, and stereos blasting noise to drown out the voices in his head. It really hadn’t been his idea to be onstage that night. He hadn’t won anything, and he hadn’t made an album in more than a decade. He might as well have had a sign around his neck: “Sixties Nostalgia Act.” But he had said yes when his friends asked him to sing. They were well intentioned—they wanted to give Roky and the crowd a feeling for what had once been, back when psychedelia was young and Roky was a sign of something else entirely.

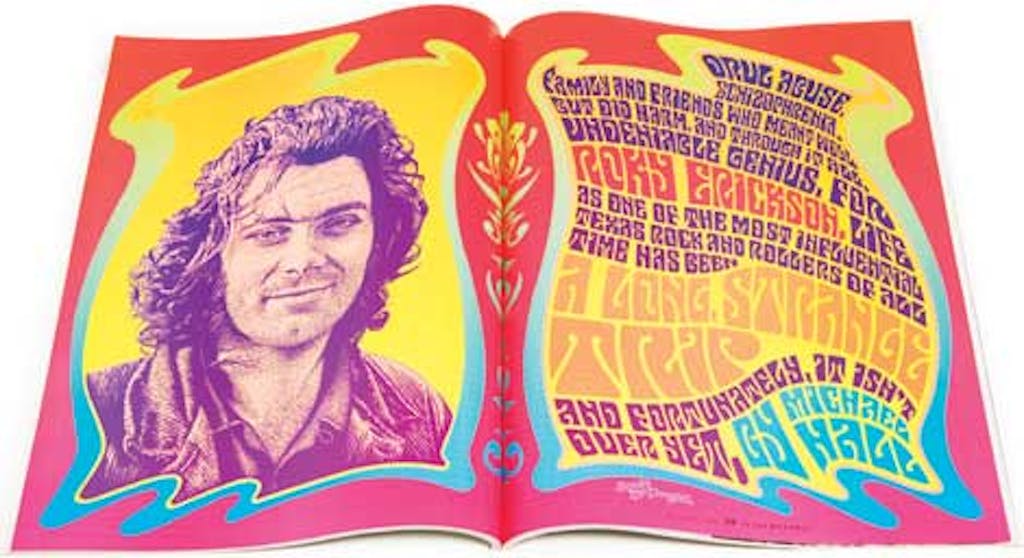

Back then, in 1966, Roky (pronounced “Rocky”) was a teenage rebel with an electric guitar. He had a sweet, round face and a buzz-saw voice, and sometimes he’d shake his head and scream like a banshee, which drove the kids crazy. He wrote hopeful, yearning melodies like his hero Buddy Holly, who had died only a few years earlier. He and his group, the 13th Floor Elevators, were the best rock and roll band in Texas. Indeed, they were the first psychedelic group ever, and they changed the sound of rock, influencing everyone from Janis Joplin and Billy Gibbons to the Grateful Dead. They sold more than 100,000 records, had a hit song, and appeared on American Bandstand. They had everything that other seminal bands of the era, like the Doors, had: vision, great musicians, and in Roky, star power.

And then he went crazy and the band broke up. At 22, Buddy Holly was dead; at 22, Roky Erickson was in an insane asylum. Drugs, excess, schizophrenia: Roky was a casualty of the times. He got out and made more music, but he always found himself back in some kind of trouble. “Roky’s story is a descent into Dante’s inferno,” says Bill Bentley, a senior vice president of publicity at Warner Bros. Records, who grew up in Houston, saw the Elevators, and became a friend of Roky’s. “I’ve never seen such brilliance accompanied by such a fall, where every wrong thing that could happen happened.” In spite of this, or maybe because of it, over the years Roky kept getting rediscovered by musicians and fans, and he became a cult star, as much for his bizarre life as for his sublime, ferocious music. (In the mid-nineties an Englishman published a fanzine called Roky Erickson and the Secret of the Universe.) “Some artists are able to cut right through everything and get you,” says punk rock icon Henry Rollins. “Brian Wilson, Sam Cooke, Roky Erickson. His voice, lyrics, and then the man himself—a sweet, likable guy who is so mysterious and obviously a genius.”

Everyone who meets Roky comes away with a story that is both funny and horrifying. Mine came when I first interviewed him, in 1984, during one of his periods of decline. I was a cub rock writer, and he had been one of my heroes ever since I’d heard “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” two and a half minutes of prehistoric garage-rock fury. Roky had long straggly hair, long nails curling out of nicotine-stained fingers, and deep creases in his forehead. After we started our interview that afternoon, he pulled the cellophane from a cigarette pack out of his shirt pocket to reveal a bee crawling around inside. He examined it briefly, returned it to his pocket, and continued, rambling on many subjects, making connections between things that weren’t the least bit connected. He said he was the rock messiah. He said he was flattered at being called the first punk rocker but pointed out that true punk was a song by fictional characters Doug and Bob McKenzie of the television show SCTV. He said he had a new song called “I Love the Sound of a Severed Head When It’s Bouncing Down the Staircase.” At one point he started talking about Satan. “The devil is the person who commands the opposite place of God,” he said. “Satan wants to crucify Jesus. I kind of like Jesus. Jesus got crucified, died for our sins. Satan was an angel who was kicked out of heaven. His name was Little Michael, Little Michael Hall …” I stopped taking notes and looked at Roky, waiting for a wink, a chuckle, a pause—anything. He ignored me. “I’m Satan and the devil is the devil,” he went on. “You always want to be the stranger in the woods, the angel Paul … ” Yes, I had heard him correctly, and either I was the Dark Lord or Roky was pulling my leg. He was obviously more in control than I had given him credit for, and all afternoon he did what he has done all his life: He danced along the line between the lucid and the scatterbrained. Perhaps, I thought, he’s crazy. Perhaps he’s pretending. Perhaps he’s both.

I saw him occasionally over the next decade and a half, but Roky became more and more reclusive, and stories about him got more dire. During most of the nineties, he lived alone in the sonic chaos of his blaring appliances. His teeth had rotted to nubs, and he was in constant pain from oral infections. As the decade wound down, he wouldn’t open the door to anyone but his mother, Evelyn Erickson, who had been caring for him. Many friends were afraid he might die. But then last year, in a tense and sometimes bitter struggle, Roky’s youngest brother, Sumner, went to court and wrestled control away from their mother, moving 54-year-old Roky to his home in Pittsburgh. Roky was back on anti-psychotic medicine. He got new teeth. He was alive.

It seemed like a good time to try to contact Roky again, to try to properly tell his story. All previous attempts have gotten lost in the swirl of fact, myth, and outright lies that make up the Roky Erickson legend. (Expect other attempts too: a Hollywood movie, a documentary, and a book on Roky and the Elevators are all in the works.) So this summer I flew to Pittsburgh and spent three days with him. Seventeen years after my first interview, he was not nearly as effusive, often letting long stretches of time go by without saying anything. Conversation with Roky is always a Zen experience, and sometimes one hand does all the clapping. He is especially reticent about his past, with good reason. For most of us the past is another country; for Roky it’s another planet. He looks better than he has in years—his beard is trimmed, his hair is short, and because of his dentures, he’s not afraid to smile. Roky used to look like Rasputin; now he looks like Jimmy Stewart’s dotty Uncle Billy in It’s a Wonderful Life. He is sweet and eager to please, and he marches around his brother’s house like a toddler might—slowly, back straight, arms out. Emotionally, Roky is still a boy, and he often tests his boundaries with Sumner.

Roky and I took a lot of drives and watched a lot of cartoons, and I became, for a short time, one of his minders, part of a long line of people over the years who have been drawn to him. Such people inevitably want to take care of him, to shield him from himself and his demons, and so they try to fashion Roky according to the image they have in their heads. They create their own versions of him. And though they try to save him, sometimes they do him harm. Throughout his life he has fought the law, doctors, the music industry, and his own schizophrenia. But some of his toughest battles have been with friends and family who, in order to maintain their versions—who he was, what he needed, what he didn’t—became fiercely protective and downright manipulative. It’s tempting to point to one villain or another in Roky’s life story, but most of the people around him have wanted to help him. They meant well—they just had their own ideas about who their favorite rock eccentric should be. “Everybody in this story has good intentions,” says Evelyn, whose intentions have been the best of all. “But you know what they say about the road to hell.”

In 1983 Evelyn shot a home video of her son playing songs. It opened with Roky singing, “For you, I’d do anything for you …” while the video camera focused on a portrait of Evelyn as a young woman. She had black hair, red lips, and fair skin and looked like Elizabeth Taylor. The camera stayed on the painting, then panned to Roky, who stopped halfway through the first chorus. “Like it?” he asked the camera in a high drawl. Evelyn’s voice told him that what he had sung was just a test run. Now they’d do the real one. Then she said, “You want to comb your hair real quick?” Roky had flowing locks, a mustache, long sideburns, and eyebrows that almost met over kind, sad eyes. His bright red-orange shirt and orange pants looked like they came from Goodwill. He did the song again (this time the camera stayed on him the whole time) and then sang nine more. Several times the camera came back to the portrait. After each song he asked some variation of “How about that one?” And Evelyn said some variation of “Good.”

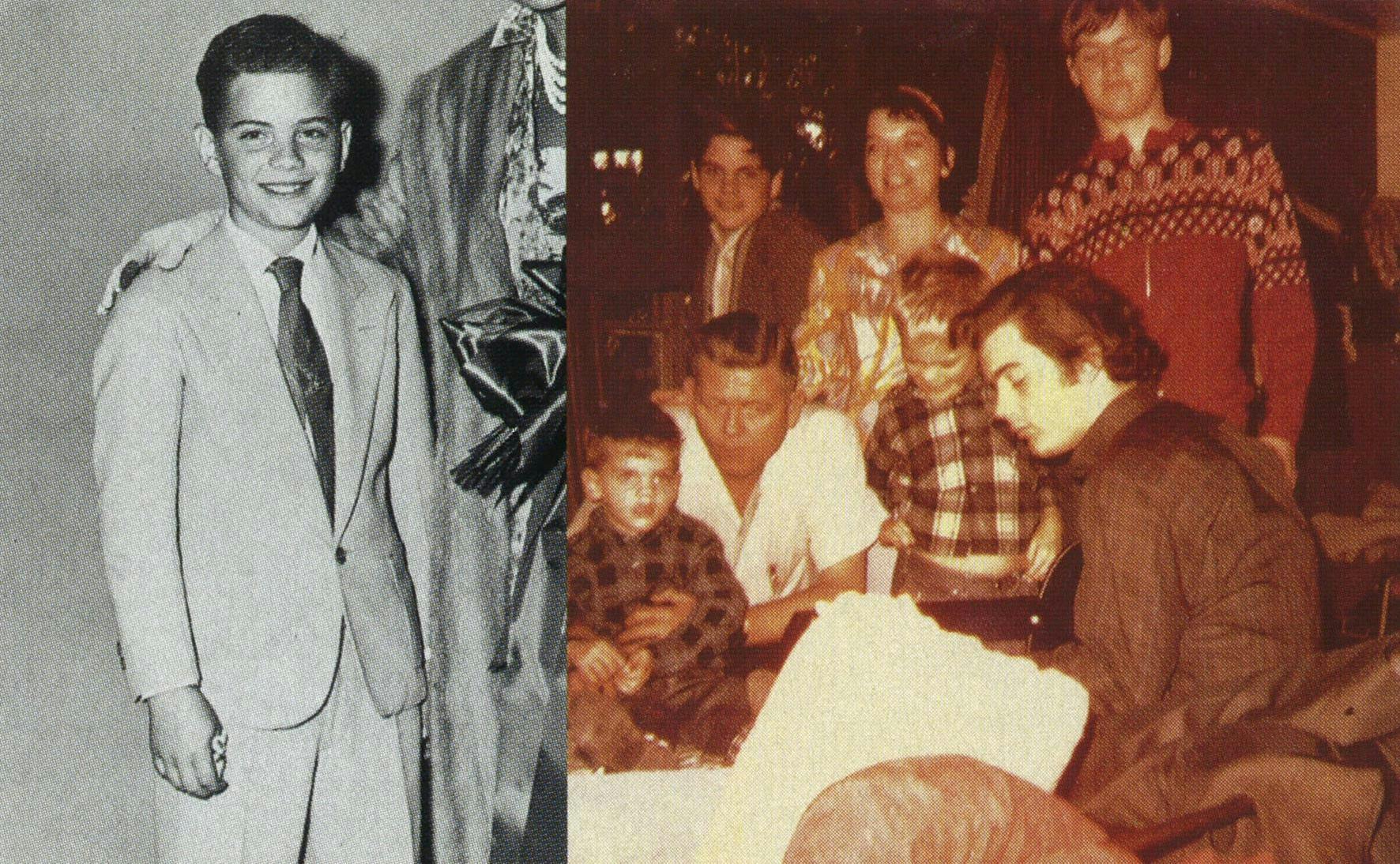

Evelyn has been Roky’s director for most of his life, his first influence and the one who made him the great and fragile artist he is. She’s artistic, iconoclastic, and self-absorbed. She’s also the one who is most to blame for Roky’s current condition, say several people close to him, who half-jokingly call her Develyn. Evelyn didn’t set out to be a Svengali. She was a high school cheerleader in Dallas who married her high school sweetheart, Roger Erickson, in 1944. Their first son, Roger Kynard Erickson, Jr., was born July 15, 1947. He was called Roky because of the first two letters of his first two names. Soon the Ericksons moved to Austin, where Roger, a civil engineer and an architect, designed and built their home on Arthur Lane in South Austin. Evelyn put Roky in piano lessons at age four. A few years later, she was taking guitar lessons and then running home to teach him. Evelyn had a strong voice and sang with the University of Texas Opera Workshop. She won an Arthur Godfrey talent contest in 1957, singing the aria of La Traviata. The next year she even released a single of “O Holy Night” on a local label. Around that time Roky, with younger brothers Mikel and Don, made his public debut, singing “Mother Dear” to Evelyn on a local TV show called Woman’s World. She sang in an Episcopal church choir, and Roky and his brothers (Ben was born in 1959 and Sumner in 1962) sang in a Baptist one. The Ericksons were devout believers, and Evelyn says that when Roky had a broken leg, her prayer group healed him.

They weren’t your typical fifties American family. When I told Evelyn that they seemed quite eccentric, she replied whimsically, “I’d prefer to call us ‘eclectic.’” Now in her seventies, Evelyn has bright eyes and a pixielike smile. “I just thought we were being creative,” she said with a laugh. George Kinney, a boyhood friend of Roky’s and now an Austin musician, remembers how the neighborhood kids loved to go to the Ericksons’, where the rules weren’t as strict as those at other homes. Another friend remembers no rules at all: “The Erickson house was often a mess—clothes everywhere, kids running amok, and Evelyn would be painting a mural across the living room wall.” Dad was a brilliant architect but a workaholic and a hard drinker who was rarely home. “Roky feared his father,” says Kinney. “We all feared his father. He was real sarcastic. Very disapproving of Evelyn’s liberal way of raising the kids.” Kinney remembers Roger coming home in the wee hours one night when he and Roky, who were growing their hair long because of the Beatles, were awake and reading comic books. Roky’s father called his son out and cut his hair.

Comics were a big part of Roky’s life—superheroes like the Fantastic Four and horror comics—as were scary movies. “He was a weirdo,” says Kinney, “but a gentle one. Real funny, popular with girls, good-looking. Not part of the crowd.” Roky loved rock and roll. His favorite was Buddy Holly, but he liked the way Little Richard and James Brown screamed, and he’d play Brown’s records and wail along. Then he heard Bob Dylan, and by 1965 Roky and George were playing guitars down on the Drag, the section of Guadalupe Street that borders UT, a tip jar at their feet. They started hanging out with college kids and early hippies. They discovered marijuana. “He started getting his confidence,” recalls Kinney. “We were all stumbling around, trying to find what we wanted to do. He found his spot.” Roky wanted to play music. He left high school three weeks shy of his 1965 graduation—whether he dropped out or was kicked out is unclear, though Evelyn says he was booted for having long hair. Soon he joined the Spades, a local group. They recorded and released one of his songs, “You’re Gonna Miss Me.” In retrospect, that wild, muffled 45 was one of the first punk-rock singles.

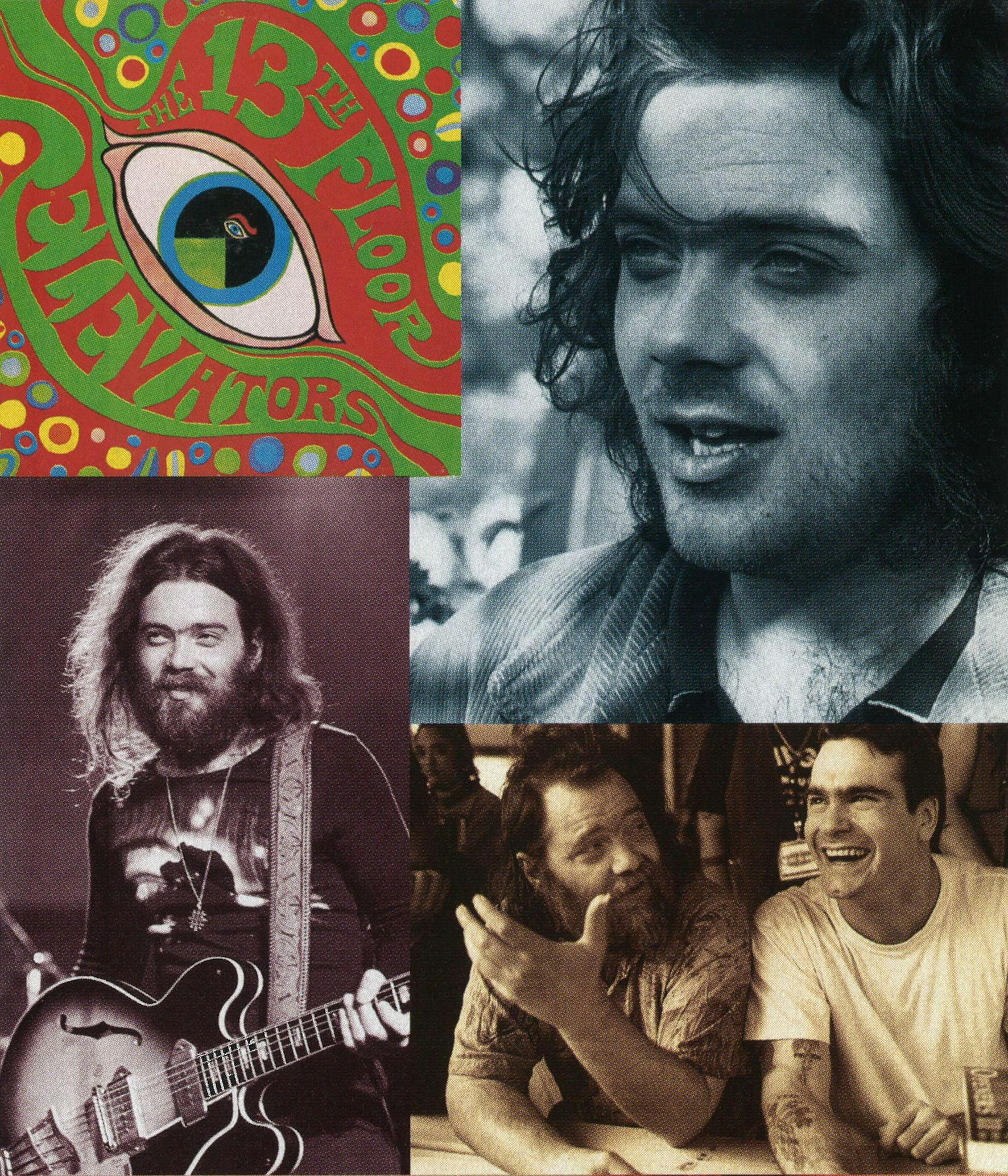

Roky now found himself part of the budding counterculture and music scene at UT. Rock bands and folkies were writing songs, smoking marijuana (which was illegal—possession was a felony and a joint could get you twenty years), and taking psychedelics like LSD and peyote, which were still legal. Roky fell in with a pushy intellectual named Tommy Hall who loved LSD and saw it as the foundation of a new philosophy. Hall couldn’t play an instrument, but he picked up the jug, a staple of many folk bands of the day, and recruited a band, stealing Roky from the Spades with the promise of a supergroup with a super philosophy: truer living through chemicals. They called themselves the 13th Floor Elevators. “If you want to get to the thirteenth floor,” Roky once explained, “ride our elevator.”

Roky wrote most of the music, but Tommy, five years older, wrote the words and set the group’s tone. Hall saw the Elevators as missionaries, and he insisted they take acid—only the best—before every show, although sometimes they played on other hallucinogens such as DMT or mescaline. “Tommy manipulated the band, and especially Roky, with LSD,” says musician Tary Owens. Hall was the teacher and Roky the child, and the Elevators quickly became the most popular band in Austin, drawing hundreds of people to clubs like the Jade Room. Nobody had ever seen a group like this. They proselytized about freeing your mind while other bands sang about cars and girls; they wrote their own songs when others were playing “Louie, Louie”; they made a weird ticka-ticka-ticka sound (it was the jug); and they were fronted by a white teenager who screamed like James Brown. “He was the most electric performer I’ve ever seen, and that includes Hendrix,” says Bill Bentley, then a Houston high school kid who would see the band at clubs like La Maison. “He was possessed, so vivid and mesmerizing. His voice was so sharp and cutting—sometimes he’d get lost in his screams.” Roky would cock his head to the right and shake it as he screamed. In early 1966 the group recorded a new version of “You’re Gonna Miss Me” for Contact, a small Houston label. Contact then sold it to International Artists (IA), another small Houston label, which released it that spring. The song became a regional hit.

It was hard to be a hippie in Texas in 1966, especially a popular one. The police were not happy about this gang of longhaired rock stars and began shadowing the group after members were busted for pot. “The police declared war on the Elevators in Texas,” IA’s Lelan Rogers (country star Kenny Rogers’ brother) once told rock writer Jon Savage. Cops would search the band’s equipment before and after shows. In Baytown the police dismantled the group’s gear in the parking lot looking for drugs, and local kids had to lend the musicians their amps. “The police thought people like Roky were out to take over the government and corrupt their children,” says Roky’s high school friend Terry Moore, now a Lake Tahoe real estate broker. The Elevators eventually lucked out on the pot arrest. They could have gone to prison, but because of a judge’s error, all went free or were put on probation.

In August the Elevators went to San Francisco, where they found another fledgling counterculture. The Texans carried a mystique with them—they were loud, they’d been busted, and wildest of all, they played on LSD. Bands like the Grateful Dead (who formed shortly after the Elevators played their first San Francisco gig) took LSD, but they didn’t play on it. These hard-edged Texans blew into town and blew people’s minds. They were psychedelic. They were the first to use the term, and soon Bay Area bands were following their lead. When “You’re Gonna Miss Me” peaked at number 55 on the Billboard pop singles chart, IA called the band back to Texas to do an album, which they recorded in eight hours. The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators came out in November, with a bright psychedelic cover and Hall’s rambling acid manifesto on the back: “Recently, it has become possible for man to chemically alter his mental state and thus alter his point of view… .”

The record was a hit, and the group began working on a follow-up, Easter Everywhere, a kind of LSD concept record. Roky conceptualized freely, ingesting whatever pills others offered him, sometimes without asking what they were. “He had to live up to his status as the weird psychedelic mutant,” remembers Kinney. Roky started getting more and more paranoid. At a November 1967 concert in Houston, he was afraid to walk onstage because he didn’t want people to see the third eye in the middle of his forehead. By then the band’s singular live show had degenerated into feedback and druggy jamming. When Bentley saw them in 1968, Roky stood with his back to the audience, singing a different song from what his bandmates were playing. “It was heartbreaking,” Bentley says. “I thought, ‘It’s over. How did that happen?’”

The Elevators scrambled to make a third album for IA, even though they had problems with the label and complained that they had never made any money beyond a weekly $50 salary. Roky was in and out of clarity. “He was a vegetable,” says bassist Ronnie Leatherman, who still plays music in Kerrville. Roky sang on only a handful of songs on the record, which was called Bull of the Woods. The band played a disastrous show at the just-opened HemisFair in San Antonio and Roky limped home. “He was all wired up and talking gibberish,” says Evelyn. “I had to worry about his effect on my other four kids.” She hired a psychiatrist, who put Roky on anti-psychotic drugs that left him in a stupor. She hired another doctor to take him off those drugs. Roky entered a private hospital in Houston, but two weeks later Hall helped him escape, and the two hitchhiked to California. Roky was free, but it was the end of the Elevators.

At a new year’s eve, 1968, show at the famous Winterland, Roky’s friend Terry Moore, who was in San Francisco to check out the legendary scene and score some good acid, saw Roky and George Kinney, who needed a ride back to Austin. It was hard to say no to Roky. “Everybody treated him like a god,” says Moore. “Nobody would say, ‘Roky, you need to straighten up.’” The three of them, plus three others, loaded into a VW Bug and headed home. Roky was in bad shape—unshaven, without shoes, and incoherent; apparently he’d been doing a lot of speed. In Arizona they broke out the LSD. Terry held out his hand and began passing it around. “I said, ‘Roky, want some?’ He grabbed a handful and put it in his mouth—took at least ten hits, and this was good acid.” Soon Roky was holding one arm and hitting himself with it, yelling, “Get out, bad spirit!” Roky’s friends dropped him off in El Paso, and he found his way back to Evelyn, freaked out and covered with sores.

In February 1969 Roky was busted for marijuana possession and eventually sent to the Austin State Hospital to be examined. He was diagnosed with “schizophrenia acute, undifferentiated” and put on the anti-psychotic drug Haldol. In May he escaped with the help of his girlfriend Dana Gaines. (She was not surprised to learn that a week before another girl had tried the same thing but she and Roky had been caught.) The police arrested Roky three months later. The best way out of a two-years-to-life sentence was to convince the judge that he was insane. Roky looked and acted crazy enough, and Dr. David Wade testified that Roky was hopeless—“a classic example of a schizophrenic reaction, a mental illness, mixed with drugs.” He was ruled insane and therefore innocent of possession. Six years later Roky would claim that he had faked the whole thing; he seemed to enjoy keeping people guessing.

Because Roky had a habit of escaping minimum-security joints, he was sent to Rusk State Hospital, a facility that housed the criminally insane in East Texas. After several years of gobbling massive amounts of LSD, speed, and any other drugs someone might offer, he was given shock treatment and massive amounts of Thorazine, a drug used to sedate psychotics. Roky later told drummer Freddie Krc how terribly he was treated: “I was in there with people who’d chopped up people with a butcher knife, and they treated me worse because I had long hair.”

The hair was cut. Evelyn visited, often bringing one of her other sons. She recorded Roky doing some of the songs he was writing—love songs and religious poems. Kinney began smuggling pages out, which he published as a book called Openers. Roky started a band, the Missing Links, with a couple of other inmates—a black guy who would perform with his face painted white and a redneck with long sideburns—and played at the hospital, rodeos, and a nearby college. Though he was doing well enough, his “open” sentence meant that unless someone proved he didn’t belong there, he could stay in Rusk for the rest of his life. In 1970 Roky’s brother Mike hired attorney Jim Simons to get him out, and Simons finally got Roky a trial in 1972. The Austin courtroom was packed. By now Roky was something of a cause célèbre, the closest thing Austin had to a rock star but also a symbol of the counterculture. The jury came back in less than fifteen minutes. Roky was not a danger to himself or others, they said, and he was discharged from Rusk, “sanity restored.”

But free Roky was confused Roky. “He didn’t know where to grasp onto life again,” says Kinney. “He depended on the largesse of friends.” Once, when Moore saw Roky walking and gave him a ride, his friend didn’t seem to recognize him and kept saying the CIA was watching him. Roky tried to get the band back together, and they even played a handful of shows. But things weren’t the same, says writer Joe Kahn, who was hanging out with the group at the time and who now writes for the Boston Globe: “There was a lot of simmering frustration and bitterness at how they’d been ripped off by International Artists.” (Roky, remembers Kahn, was oblivious to the problem.) Soon Roky and Dana Gaines got married. At first he was taking his meds and was happy. Soon, though, he went through a violent period. Dana recalls, “Out of the blue, he would go into rages. I was black and blue.” She says that he once attacked her in her sleep. Roky would also take out a copy of Openers and cross out “Jesus” in his religious poems and write in “Satan.” After nine months he stopped attacking his wife, and around then he had an affair with a woman named Renee Bayer that produced his first child, a girl named Spring, in 1974.

From 1973 to roughly 1982, Roky bounced back and forth between Austin and the Bay Area. He played with a band called the Aliens and recorded a couple of stunning new songs, “Starry Eyes” and “Two Headed Dog (Red Temple Prayer),” with Doug Sahm. The songs would become two of his best known and would road-map the way he wrote for the next decade—a singular mixture of angelic love songs and demonic rock. “Starry Eyes” sounded like a Buddy Holly gem, while “Red Temple Prayer” was a ferocious slab of hard-edged guitar. Roky’s new kick was that he was an alien from Mars; he claimed he had the legal documents to prove it and that “You’re Gonna Miss Me” really meant “You are gonna miss a Martian E.” He was writing songs about ghosts, vampires, and beasts. Perhaps they were a reaction to the hell of Rusk State Hospital or perhaps he just wanted to shock people. Even though his new songs had titles like “I Walked With a Zombie,” his melodies were still gorgeous, sometimes with a fifties-era innocence. A friend of his once asked him where his melodies came from. He paused, then said, “The very best ones are sent from heaven by Buddy Holly. The rest take the better part of an afternoon to rip off.”

Roky signed a management and publishing contract and seemed to be getting his life in order. But in 1979 Dana, who was tired of Roky not taking his medicine and worried about how his antics were affecting their three-year-old son, Jegar, drove Roky from San Francisco to Austin and left him with Evelyn. Roky was soon discovered by local punk rockers, and he played with avant-weirdos the Re*Cords and then the new-wave band the Explosives. In 1980 he made his first full solo album (its title is a bunch of runic symbols) for CBS in England, where he had a devoted following. He was taking his medicine again, though producer Stu Cook later told an interviewer that Roky didn’t like how it made him shake and wobble. “Roky would often say that he’d rather be nuts …than the way he felt,” said Cook. As soon as Roky started feeling better, he’d go off the medicine and start taking speed and any other drugs his friends gave him. Divorced from Dana, he married a former bartender named Holly Patton, with whom he had a daughter named Cydne in 1984.

But Holly left too, and Roky wound up living with friends. Roky was always surrounded by friends. One of them was Jack Ortman, a fan who had been collecting everything ever written about Roky. In 1986 Ortman released the first of four volumes of Roky scrapbooks—it had more than three hundred pages, a sign of how vast Roky’s influence was. Though CBS rejected a second album, small labels in the U.S. and Europe were releasing various studio and live bootleg albums, many recorded and released by Roky’s friends. In 1987 Roky played his last full show, at Austin’s Ritz Theater, and it too was eventually released as a live album. At the end of the show you can hear Roky calling out to his audience, “Thank you! Thank you! I really enjoyed the show! Thank you for playing tonight!” Inscrutable and lovable, he was a full-blown cult hero.

But there wasn’t much money coming in to support Roky or Evelyn, who had been separated from her husband since 1979 and who had power of attorney over her son. She’d cash his Social Security mental-disability checks and give him $20 every other day for food and cigarettes. She moved him to federally subsidized housing in Del Valle, southeast of Austin. Roky shared a mailbox with two other tenants, including a friend of his. Roky would collect the mail for all three and take it to his friend, who would distribute it. When the friend moved out, Roky continued to collect the mail for all three addresses. Around Christmas a new tenant figured out why she wasn’t getting any mail and called the police, who found it unopened and tacked on the wall near Roky’s front door. Though Roky had clearly not intended to steal her mail, he had committed a federal offense, and this time he was sent to a federal mental institution in Missouri. He eventually wound up back in the Austin State Hospital, where he was given therapy and medicine for sixty days and then released. Roky immediately stopped taking his meds, and visitors to his home would walk in on a bunch of TVs, radios, stereos, and police scanners blaring white noise. Roky called the noisemakers his “electronic friends” for hiding the voices in his head.

As the nineties began it seemed like Roky would finally get some of the recognition he deserved and the money he was owed. On Halloween, 1990, Where the Pyramid Meets the Eye was released by Sire—a nineteen-track compilation of Roky’s songs done by rock stars he had influenced, such as REM and ZZ Top. Several trusts were set up to organize Roky’s finances. Attorneys hired by Evelyn, working pro bono, began a ten-year battle to get back royalties from International Artists; they claimed that though the band had sold many records, members had never received any royalties from label owner Lelan Rogers (who would soon sell the Elevators catalog to Charly Records in England, meaning the attorneys would now have to go after them). Roky began playing in public again at the urging of his friends, first at birthday parties and then at the Austin Music Awards. Unfortunately, he played the same four songs at every appearance. During one performance, when Roky forgot the words to one of his songs, Bill Bentley says, “I realized that he had no business being up there, and I might have helped push him up there.”

Roky made it through the past decade because of a steady group of minders who, along with his mother, took care of him. They’d go to his house, marvel at the noise and mess (in the wake of his mail bust, Roky had become obsessed with getting mail, writing away for every free catalog he could get), take him out to dinner, drive him around, hang out at Evelyn’s—the one place Roky would relax—and marvel at his resilient way of seeing the world. Once, on an election day, Roky, Casey Monahan (the director of the Texas Music Office), and Butthole Surfers drummer King Coffey were driving around when Coffey asked Roky if he had voted. “I’m voting right now,” he replied. Most of his minders were music business veterans like Monahan, musicians Owens and Coffey, freelance journalist Rob Patterson, and Emperor Jones label owner Craig Stewart. All seemed to see in Roky qualities that made them fall in love with rock and roll in the first place. As Monahan says, “He’s a guy who’s been screwed so many times but still looks at the world with an innocence completely at odds with his experience.”

In 1993 Monahan, with help from Roky’s brother Sumner, began collecting all of Roky’s songs and poems; two years later they were published as Openers 2. Monahan also got Roky back in the studio again, for the first time in a decade, to record six old songs that were combined with five that were already recorded; the result was All That May Do My Rhyme. Roky’s voice wasn’t as strong as it once was, but it’s a gorgeous album and one on which you can hear his true genius—his love songs. Roky’s melodies will break your heart, from the luminous “Starry Eyes” to the soulful “You Don’t Love Me Yet.” Sumner played tuba on the album and was getting more and more involved in Roky’s life. Like his brother, Sumner had been a teen prodigy, though he had followed a different path. He started playing the tuba in junior high school and was asked to join the prestigious Andre Previn-led Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra when he was only eighteen.

Sumner wanted his brother back on medication, but Evelyn wouldn’t hear of it and neither would Roky. They didn’t trust doctors. Evelyn thought Roky’s friends were the best medicine he could have, and she distrusted anti-psychotic drugs. She told me that Haldol, which Roky had taken in 1968, gave him the shakes and made him walk like a zombie. “You have to be careful,” she says. “These psychotropic drugs should be monitored very seriously. If they’re going to treat your mind, they should look at your whole body. Look at all the people who’ve died because of drugs.” Evelyn’s antipathy to prescription drugs comes partly from Roky’s experience with hallucinogens. Evelyn and Roky didn’t seem to trust dentists either. Roky’s teeth were rotting in his gums, and he was in a lot of pain, but still, remembers Patterson, “He’d say, ‘I’m not going to the dentist!’ And Evelyn would say, ‘Roky, if you don’t want to go to the dentist, that’s okay.’” Evelyn often said that what Roky needed was more people praying for him.

But Roky’s minders think there was more to her refusal. “It was to protect her relationship with Roky,” says Owens, “to protect her control over his life.” There was a degree of madness behind her method, says Monahan: “Every woman Roky has ever been close to was ostracized by Evelyn. The only way for her to keep control was no girlfriend, no prescription drugs, no therapy. She seems to gain her identity from being his caretaker.” Warner Bros. Records executive Bentley disagrees. “I never saw the dark side of Evelyn,” he says. “She tried to cure Roky in so many ways, according to her belief. She might have loved him too much. He was her oldest, the most talented. He was a star, a little God-like creature.”

Besides, Bentley says, picking on Evelyn misses an important point. “It’s easy to say Evelyn told him not to take his meds,” he says. “I think Roky liked the nothingness of his life. There was too much gigging and practicing.” Roky is the king of the lollygaggers, and even as he has attracted people to him, bringing out their best—a sense of wonder, a nurturing instinct, a rush of gratitude that gentle weirdos like him walk among us—he has allowed them to take advantage of him, to turn him on, prop him up, trumpet his resurrection and their place alongside him. Roky, who is smarter, stronger, and more aware than anyone gives him credit for, is his own worst enemy: relentlessly passive. As his old friend Kinney says, looking back on Roky’s life, “Sometimes I think he just didn’t want to get a job, and he’s pulled it off beautifully.”

Last year Sumner decided enough was enough: Roky had a disease and he needed treatment. Sumner was angry that his 52-year-old brother, who was then living in a small federally subsidized apartment in South Austin, hadn’t been seen by a doctor in ten years. In January of this year, Sumner applied for guardianship. In May a psychiatrist who had visited Roky filed a report with a Travis County court saying that abscesses in Roky’s teeth were in danger of infecting his brain. Soon after, Roky was admitted to Shoal Creek Hospital, where he got two weeks of medical, dental, and psychological exams. Again he was diagnosed with schizophrenia, “a biological, genetic illness,” says his doctor, William Privitera, that was probably waiting to happen in 1969, “though perhaps it got sped up by drug use.” He was put on Zyprexa, one of a newer breed of anti-psychotics, by Privitera, who says it doesn’t have the side effects of the older medications like Haldol: “It helps him think more clearly, it reduces his auditory hallucinations, helps with his attention, and reduces his agitation.” Though Evelyn says Roky was anxious to leave the hospital, other family members saw immediate progress. “He shook my hand and asked about my kids,” says his brother Mike. “He’d never done that before.”

Evelyn visited Roky in the hospital every day. He asked her to cut his hair, which had grown into a massive dreadlock, and she did. She knew that the doctors were against her. “Theirs is an unhealthy, enmeshed relationship,” says Privitera. “It’s difficult to tell where she stops and he starts. We need to give Roky an opportunity to come into his own—to see what life without Mom can be.” At the June 11 guardianship hearing, Evelyn voiced her distrust of Roky’s medicine. “I would rather see the psychologists use methods more humane, more holistic, like yoga,” she said. The judge thought more drastic action was needed and made Sumner Roky’s guardian. Sumner felt he had to get Roky out of Austin, and nine days later they flew to Pittsburgh.

Once when he was a young boy, Sumner sat in the living room on Arthur Lane and listened to his big brother practice. Later he’d visit him in the insane asylum. Now he leaves him cheerful Post-it notes in his kitchen—“Dear Roky: Good Mornin’! I hope you had a good rest. Here’s your 8 am med.” He plans to raise $1 million through a new trust so that he can eventually buy his brother a home in Austin and support him for the rest of his life. “If a hundred thousand people each give ten dollars, there’s a million,” he says confidently. On the wall just around the corner from the kitchen is a drawing Roky made of Tubby the Tuba when he was a boy, years before Sumner was born. Sumner is convinced Roky had something to do with him hearing his calling. On the mantelpiece is a sculpture of a beautiful woman, done by the famous artist Charles Umlauf, an Erickson family friend. The woman is Evelyn.

“Roky looks good,” his rather taciturn father, Roger, says one evening. Roger, who designed Sumner’s ultramodern home, lives next door yet doesn’t see Roky much. Neither Roky nor Sumner seem particularly close to him. Indeed, Roky looks to Sumner for all things parental, asking him for permission like a child, sometimes testing his authority. Sumner, fifteen years younger, is patient and fair. Mostly Roky likes to watch the Cartoon Network and ride around in their dad’s big blue New Yorker with the radio tuned to his favorite Top 40 station (Roky hasn’t driven in years, terrified of getting stopped by the police). Roky is eating well, though he probably smokes a pack a day, dragging deeply on each one, exhaling, and almost immediately inhaling again. He doesn’t drink or do any kind of illicit drugs. He loves ice cream. He loves his new teeth and is no longer ashamed of his smile. (Evelyn says she had wanted to get Roky’s teeth fixed in 1994 with a root canal and caps, trying to save what teeth Roky had left, but the procedure was too expensive, so she never did it.) Sumner says that after years of not seeming to be interested in women, Roky is eyeballing them again. He likes going to talk to “this lady” who is helping him relax—Kay Miller, a new-age psychophysical therapist and Sumner’s “mentor” of twelve years who is seeing Roky thrice weekly. The only thing Roky doesn’t like is the tuba playing. “How about we go to your hotel and watch TV?” he said to me one afternoon when it was time for Sumner to practice.

On one of our drives, I asked Roky what he missed most about Austin and he said, “I miss my mother.” He hasn’t talked to her since a phone call on his birthday in July; Sumner says she tried to talk Roky out of taking his meds, so Sumner began blocking her calls. Sumner is just as determined as Evelyn was to have things his way, by his rules, and that means no contact with Mother. Without Evelyn, Roky’s past six months have been a paradigm shift as drastic as the one he was forced to undergo in 1969, when he went from living on LSD to living on Thorazine.

And though Sumner is kind to Roky, his way is not all sweetness and light. He is extremely bitter about Evelyn and vowed long ago never to return to her house—his childhood home—again. “Sumner is so wonderful,” says Roky’s ex-wife Dana, “but I hate it that he’s got this anger inside him.” Indeed, it borders on hatred, as strong as Roky’s love. It’s a sign of how upset Sumner is, how hard he’s pulling in his direction, that he doesn’t realize how irrational he sometimes sounds when he talks about Evelyn. “Every time he brings up his mother to me, he talks about what a horrible person she is,” says Monahan. “He wants everyone to know what a better job he is doing with Roky. He saved his brother’s life—why isn’t that enough?” Not everyone is happy with the way Sumner has gone about it. Dana worries that Sumner’s mentor, Miller, a woman in her seventies like Evelyn, will shift Roky’s dependency and become another Evelyn. Then there’s the money: attorneys hired by Evelyn finally reached a settlement with Charly (the company that bought the rights to Roky’s material from IA) that would have put more than $100,000 in Roky’s trust, but Sumner, the new guardian, has held up the deal for months so that he and his attorneys can scrutinize it further. And there are complaints that for too long Sumner has kept Roky away from his home, Austin, and his son, Jegar, who lives there (Spring lives in Houston and Cydne in Williamsport, Pennsylvania).

And, of course, Evelyn. At some point Roky will finally return to Evelyn’s world in Austin—“We’re taking it a day at a time,” said Sumner in October. “It could be two months, it could be eight”—and Sumner will go back to Pittsburgh and Sumner’s version of Roky will meet Evelyn’s. She is still angry and hurt over the way Sumner and the state took Roky away, and she filed a 75-page complaint with the Board of Medical Examiners about the whole affair. When I told her that Roky said he missed her, she said she missed him too. She was dismayed when I told her he was smoking a lot. “I had him down to ten cigarettes a day,” she says. “This worries me. The drugs cause you to overeat and oversmoke.” She’s concerned about Roky getting diabetes. She fills her days practicing the piano and doing yoga. Ever the iconoclast, she marched in an October anti-war demonstration and got her picture in the paper. She sings at church and at an open mike every once in a while with a little jazz band, doing a couple of old songs. On one such evening I was reminded again of Roky’s debt to her when I noticed how she cocked her head to the right as she sang “September Song,” just like she must have done fifty years ago when her son mimicked her every move. She didn’t shake it, though; that was Roky’s idea.

One night I asked Roky if he felt like playing the guitar. “Oh, no,” he said. But then he drawled, “I also play organ a lot.” My ears perked up; it was in the vicinity of such logic that the real Roky emerged. So you do play guitar some? “Yeah, just not in public.” Do you think you ever will? “I don’t really think so,” he said, laughing nervously. “I hope not.” Are you writing any songs? “Sometimes I write. I’ve got some ideas in my head right now.” For songs? “Uh-huh.” Are they going to be different? “I don’t know.” Then, after a pause, he asked, “Where are we?” He was changing the subject. But I had become one of those well-intentioned meddlers and I pushed him, saying I hoped he’d write and perform again. “Uh-huh,” he responded warily. Then I said how a lot of people would love to see him play again. Roky was silent. He was not going to be led somewhere he didn’t want to go. It was creepy how easy it was to take advantage of Roky’s childlike nature and humbling how firm he was in rejecting me. He was testing his limits, trying, it seemed, to come up with a version of himself he can live with.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Longreads

- Austin Music

- Austin